Within the Secret State:The Directorate of Military Intelligence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dodannualreport20042005.Pdf

chapter 7 All enquiries with respect to this report can be forwarded to Brigadier General A. Fakir at telephone number +27-12 355 5800 or Fax +27-12 355 5021 Col R.C. Brand at telephone number +27-12 355 5967 or Fax +27-12 355 5613 email: [email protected] All enquiries with respect to the Annual Financial Statements can be forwarded to Mr H.J. Fourie at telephone number +27-12 392 2735 or Fax +27-12 392 2748 ISBN 0-621-36083-X RP 159/2005 Printed by 1 MILITARY PRINTING REGIMENT, PRETORIA DEPARTMENT OF DEFENCE ANNUAL REPORT FY 2004 - 2005 chapter 7 D E P A R T M E N T O F D E F E N C E A N N U A L R E P O R T 2 0 0 4 / 2 0 0 5 Mr M.G.P. Lekota Minister of Defence Report of the Department of Defence: 1 April 2004 to 31 March 2005. I have the honour to submit the Annual Report of the Department of Defence. J.B. MASILELA SECRETARY FOR DEFENCE: DIRECTOR GENERAL DEPARTMENT OF DEFENCE ANNUAL REPORT FY 2004 - 2005 i contents T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S PAGE List of Tables vi List of Figures viii Foreword by the Minister of Defence ix Foreword by the Deputy Minister of Defence xi Strategic overview by the Secretary for Defence xiii The Year in Review by the Chief of the SA National Defence Force xv PART1: STRATEGIC DIRECTION Chapter 1 Strategic Direction Introduction 1 Aim 1 Scope of the Annual Report 1 Strategic Profile 2 Alignment with Cabinet and Cluster Priorities 2 Minister of Defence's Priorities for FY2004/05 2 Strategic Focus 2 Functions of the Secretary for Defence 3 Functions of the Chief of the SANDF 3 Parys Resolutions 3 Chapter -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

Scaped from Custody and Fled to the Republic of South Africa

REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEAL OF SOUTH AFRICA Case Number : 317 / 97 In the matter between : DARRYL GARTH STOPFORTH Appellant and THE MINISTER OF JUSTICE First Respondent THE TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION (AMNESTY COMMITTEE) Second Respondent THE GOVERNMENT OF NAMIBIA Third Respondent THE MINISTER OF SAFETY AND SECURITY Fourth Respondent Case Number : 316 / 97 And in the matter between : LENNERD MICHAEL VEENENDAAL Appellant and THE MINISTER OF JUSTICE First Respondent THE COMMISSION FOR TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION (AMNESTY COMMITTEE) Second Respondent THE GOVERNMENT OF NAMIBIA Third Respondent THE MINISTER OF SAFETY AND SECURITY Fourth Respondent COMPOSITION OF THE COURT : Mahomed CJ; Olivier JA; Melunsky, Farlam and Madlanga AJJA DATE OF HEARING : 7 September 1999 DATE OF JUDGMENT : 27 September 1999 Jurisdiction of Amnesty Committee to grant amnesty for offences committed by South African citizens outside the Republic; extradition. JUDGMENT 2 OLIVIER JA OLIVIER JA [1] In these appeals, similar questions of law have been raised. It is convenient to deal with the appeals at one and the same time. [2] It is common cause that Messrs Stopforth and Veenendaal (citizens of the Republic of South Africa) were, during the incidents described herein, members of what is generally referred to as right-wing Afrikaner organisations, inter alia the AWB (Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging) and the Orde Boerevolk. During or about 1989 they, as well as one Klentz, were approached in the RSA by one Brown to participate in underground terrorist activities in the territory then known as South West Africa (“SWA”). The three of them, as well as others, gathered in SWA, where they were issued with weapons of war: rifle grenades, anti-personnel and anti-tank missiles, phosphorous grenades, explosive devices and rifles. -

Year of Fire, Year of Ash. the Soweto Revolt: Roots of a Revolution?

Year of fire, year of ash. The Soweto revolt: roots of a revolution? http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.ESRSA00029 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Year of fire, year of ash. The Soweto revolt: roots of a revolution? Author/Creator Hirson, Baruch Publisher Zed Books, Ltd. (London) Date 1979 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1799-1977 Source Enuga S. Reddy Rights By kind permission of the Estate of Baruch Hirson and Zed Books Ltd. Description Table of Contents: -

The Role of Non-Whites in the South African Defence Force by Cmdt C.J

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 16, Nr 2, 1986. http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za The Role of Non-Whites in the South African Defence Force by Cmdt C.J. N6thling* assisted by Mrs L. 5teyn* The early period for Blacks, Coloureds and Indians were non- existent. It was, however, inevitable that they As long ago as 1700, when the Cape of Good would be resuscitated when war came in 1939. Hope was still a small settlement ruled by the Dutch East India Company, Coloureds were As war establishment tables from this period subject to the same military duties as Euro- indicate, Non-Whites served as separate units in peans. non-combatant roles such as drivers, stretcher- bearers and batmen. However, in some cases It was, however, a foreign war that caused the the official non-combatant edifice could not be establishment of the first Pandour regiment in maintained especially as South Africa's shortage 1781. They comprised a force under white offi- of manpower became more acute. This under- cers that fought against the British prior to the lined the need for better utilization of Non-Whites occupation of the Cape in 1795. Between the in posts listed on the establishment tables of years 1795-1803 the British employed white units and a number of Non-Whites were Coloured soldiers; they became known as the subsequently attached to combat units and they Cape Corps after the second British occupation rendered active service, inter alia in an anti-air- in 1806. During the first period of British rule craft role. -

![THE HISTORY of the PIETERSBURG [POLOKWANE] JEWISH COMMUNITY by CHARLOTTE WIENER Submitted in Fulfillment of the Requirements](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3136/the-history-of-the-pietersburg-polokwane-jewish-community-by-charlotte-wiener-submitted-in-fulfillment-of-the-requirements-883136.webp)

THE HISTORY of the PIETERSBURG [POLOKWANE] JEWISH COMMUNITY by CHARLOTTE WIENER Submitted in Fulfillment of the Requirements

THE HISTORY OF THE PIETERSBURG [POLOKWANE] JEWISH COMMUNITY by CHARLOTTE WIENER Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject JUDAICA at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: MR CEDRIC GINSBERG NOVEMBER 2006 SUMMARY Jews were present in Pietersburg [Polokwane] from the time of its establishment in 1868. They came from Lithuania, England and Germany. They were attracted by the discovery of gold, land and work opportunities. The first Jewish cemetery was established on land granted by President Paul Kruger in 1895. The Zoutpansberg Hebrew Congregation, which included Pietersburg and Louis Trichardt was established around 1897. In 1912, Pietersburg founded its own congregation, the Pietersburg Hebrew Congregation. A Jewish burial society, a benevolent society and the Pietersburg-Zoutpansberg Zionist Society was formed. A communal hall was built in 1921 and a synagogue in 1953. Jews contributed to the development of Pietersburg and held high office. There was little anti-Semitism. From the 1960s, Jews began moving to the cities. The communal hall and minister’s house were sold in 1994 and the synagogue in 2003. Only the Jewish cemetery remains in Pietersburg. 10 key words: 1] Pietersburg [Polokwane] 2] Zoutpansberg 3] Anglo-Boer War 4] Jew 5] Synagogue 6] Cemetery 7] Rabbi 8] Hebrew 9] Zionist 10] Anti-Semitism ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the following: Mr Cedric Ginsberg, my supervisor, for his invaluable assistance, patience and meticulous corrections The late Mr Wally Levy for his information concerning families and events in the Northern Transvaal. His prodigious memory was extremely helpful to me My husband Dennis and children Janine, Elian and Mandy, for their patience with my obsession to finish this thesis. -

We Were Cut Off from the Comprehension of Our Surroundings

Black Peril, White Fear – Representations of Violence and Race in South Africa’s English Press, 1976-2002, and Their Influence on Public Opinion Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Universität zu Köln vorgelegt von Christine Ullmann Institut für Völkerkunde Universität zu Köln Köln, Mai 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The work presented here is the result of years of research, writing, re-writing and editing. It was a long time in the making, and may not have been completed at all had it not been for the support of a great number of people, all of whom have my deep appreciation. In particular, I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Michael Bollig, Prof. Dr. Richard Janney, Dr. Melanie Moll, Professor Keyan Tomaselli, Professor Ruth Teer-Tomaselli, and Prof. Dr. Teun A. van Dijk for their help, encouragement, and constructive criticism. My special thanks to Dr Petr Skalník for his unflinching support and encouraging supervision, and to Mark Loftus for his proof-reading and help with all language issues. I am equally grateful to all who welcomed me to South Africa and dedicated their time, knowledge and effort to helping me. The warmth and support I received was incredible. Special thanks to the Burch family for their help settling in, and my dear friend in George for showing me the nature of determination. Finally, without the unstinting support of my two colleagues, Angelika Kitzmantel and Silke Olig, and the moral and financial backing of my family, I would surely have despaired. Thank you all for being there for me. We were cut off from the comprehension of our surroundings; we glided past like phantoms, wondering and secretly appalled, as sane men would be before an enthusiastic outbreak in a madhouse. -

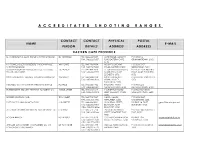

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

Sweepslag Oktober 2014

JAARGANG 1 UITGAWE 6 OKTOBER 2014 REBELLIE HERDENKING 20 SEPTEMBER 2014 Op 20 September 2014 het die AWB die Rebellie van 1914 gevier. Op hierdie koue Saterdagoggend is daar by die Kommandosaal te Coligny bymekaargekom om die brawe burgers, soos Genl. Koos De la Rey, se opstand teen die Britse oproep om saam met hulle die wapen op te neem teen Duitsland, te herdenk. Die gasheer van die dag was Brigadier Piet Breytenbach van die Diamantstreek wat saam met sy mense arriveer het met ’n perdekommando. Na ’n kort verwelkoming van Brig. Piet is die eerste gasspreker, Mnr. Paul Kruger van die Volksraad, aan die woord gestel. Na sy treffende boodskap is almal vermaak deur ’n uitmuntende tablo wat deur Brig. Piet en sy mense van die Diamantstreek aangebied is. Die tablo is geneem uit die verhoogstuk "Ons vir jou Suid-Afrika" en is briljant aangebied - almal was selfs aangetrek in histories-korrekte uitrustings! Na die boodskap van Mnr. Frans Jooste van die Kommandokorps is die oggend by Coligny afgesluit met die sing van "Die lied van jong Suid-Afrika" en almal het na Lichtenburg vertrek vir die verrigtinge daar. Daar is bymekaargekom by die standbeeld van Genl. De la Rey waar almal, te midde van groot belangstelling van die plaaslike bevolking, met trots die aankoms van die ossewa by die standbeeld toegekyk het. Na ’n kranslegging deur die Leier, Mnr. Steyn von Rönge, die sprekers en lede van die publiek, is Professor A.W.G. Raath aan die woord gestel om almal bietjie meer van die geskiedenis van die Rebellie te vertel. -

Music to Move the Masses: Protest Music Of

The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Music to Move the Masses: Protest Music of the 1980s as a Facilitator for Social Change in South Africa. Town Cape of Claudia Mohr University Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Music, University of Cape Town. P a g e | 1 A project such as this is a singular undertaking, not for the faint hearted, and would surely not be achieved without help. Having said this I must express my sincere gratitude to those that have helped me. To the University of Cape Town and the National Research Foundation, as Benjamin Franklin would say ‘time is money’, and indeed I would not have been able to spend the time writing this had I not been able to pay for it, so thank you for your contribution. To my supervisor, Sylvia Bruinders. Thank you for your patience and guidance, without which I would not have been able to curb my lyrical writing style into the semblance of academic writing. To Dr. Michael Drewett and Dr. Ingrid Byerly: although I haven’t met you personally, your work has served as an inspiration to me, and ITown thank you. -

A Survey of Race Relations in South Africa. INSTITUTION South African Inst

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 104 982 UD 014 924 AUTHOR Horrell, Muriel, Comp.; And Others TITLE A Survey of Race Relations in South Africa. INSTITUTION South African Inst. of Race Relations, Johannesburg. PUB DATE Jan 75 NOTE 449p.; All of the footnotes to the subject matter of the document may not be legible on reproduction due to the print size of the original document AVAILABLE FROM South African Institute of Race Relations, P.O. Box 97, Johannesburg, South Africa (Rand 6.00) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$22.21 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Activism; Educational Development; Educational Policy; Employment Trends; Federa1 Legislation; Government Role; Law Enforcement; *National Surveys; *Politics; *Public Policl,; *Race Eelations; Racial Discrimination; Racial St!gregation; Racism IDENTIFIERS *Union of South Africa ABSTRACT Sections of this annual report deal with the following topics: political and constitutional developments--the white population group, the colored population group, the Indian group; political affairs of Africans; commissionof inquiry into certain organizations and related matters; organizations concerned with race relations; the population of South Africa; measuresfor security and the control of persons; control of media of communication; justice; liberation movements; foreign affairs; services and amenities for black people in urban areas; group areas and housing: colored, Asian, and whitd population groups; urban African administration; the Pass laws; the African hoL_lands; employment; education: comparative statistics, Bantu school -

On Apartheid

1-1. " '1 11 1~~~_ISl~I!I!rl.l.IJ."""'g.1 1$ Cl.~~liíilII-••allllfijlfij.UlIN.I*!•••_.lf¡.II••t $l.'.Jli.1II¡~n.·iIIIU.!1llII.I••MA{(~IIMIl_I!M\I QMl__l1IlIIWaJJIl'M-IIII!IIIll\';I-1lII!l i I \ 1, ¡ : ¡I' ADDITIONAL REPORTS OF THE ON APARTHEID • GENERAL ASSEMBLV OFFICiAL RECORDS: TWENT\(-NINTH SESSION SUPPLEMENT No. 22A (A/9622/Add.1) ..", UNITED NATIONS 22A 1, ¡1 ,I ~,,: I1 I ADDITIONAL REPORTS OFTHE SPECIAL COMMITrEE ON APARTHEID • GENERAl. ASSEMBLY OFFICIAL RECORDS: TWENTY..NINTH SESSION SUPPLEMENT No. 22A (A/9622/Add.1) UNITED NATIONS New York, 1975 . -_JtlItIII--[iII__I!IIII!II!M'l!W__i!i__"el!~~1'~f~'::~;~_~~".__j¡lII""'''ill._.il_ftiílill§~\j . '; NOTE Syrnbols of United Natíons documents are composed of capital letters combined wíth figures. Mentíon of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations documento The present volume contains the four additional reports submitted to the General Assembly, at its request, by the SpeciaI Committee on Apartheid. They were previously issued in mimeographed form under the symbols A/9780, A/9781, A/9803 and A/9804 and Corr.l , l' r1: ¡~,f.•.. L ,; , ",!, <'o,, - -'.~, --~'-~-...... ~-- •.• '~--""""~-'-"-"--'.__•• ,._.~--~ •• __ •• ~ ~"" - -,,- ~,, __._ 0-","" __ ~\, '._ .... '-i.~ ~ •. /Original: English/ CUNTENTS Page . PART ONE. REPORT ON VIOLATIONS OF THE CHARTER OF THE J"" UNITED NATIONS AND RESOLUTIONS OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY AND THE SECURITY COUNCIL BY THE SOUTH AFRICAN REGlME ••••••••••••• • •• • • •• • PART TWO. REPORT ON ARBITRARY LAWS AND REGULATIONS ENACTED AND APPLIED BY THE SOUTH AFRICAN REGlME TO REPRESS THE LEGITlMATE STRUGGLE FOR FREEDOM •••••••••• e•••••••••• ¡, • •• 22"" PART THREE.