7Jf4hereis a Small Red-Figuredstemless Cup in London(B.M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ependytes in Classical Athens

THE EPENDYTES IN CLASSICAL ATHENS (PLATES 51-55) To the memoryof Richard D. Sullivan T HE FEW REFERENCES to the ependytes in Classical Greek literature occur in three fragments of Attic drama preserved by Pollux (VII.45): XLTWV EpELSSXLTCTVLOTKOS' XLTCeJVLOV, LaTLOV. ETEL E KaL 0 E(XEV8VVT7)S- EOTLV EV T7 TCV 7OXX XP7OEL, OOTLS' /3OVXOLTO KaL TOVTC TO ovo4LalTL /07)OE^LV .avIX() OVTL, XA7pTTEOvavro EK TCeV 1o00OK\EOVS1 IXvvTpLCOV (TrGF, F 439): 7rE-atXOVSTE v77oaL XLVOYEVE^LST' E'JTEv8VTas. KaL ?EOT7LS UE 7TOVO')TLV EV T^ HEvOEZL(TrGF, I, F 1 c): 'pyq( VOMLJ'EVE/3PL' EXELTEV 3VT7_VV. aVTLKPVS'86E OKELTO E'VTi- NLKOXacpovs,'HpaKXEL X0PopYW (I, p. 771.5 Kock): 4pEPEVVZV TaXECos, XLTCvJa TOVO E7XEV8VTflV Tf VVVXP/3VVXEL EL LV. The lines are disappointingly undescriptive,indicating only that an ependytes can be of linen and is somehow associatedwith the chiton, and that at an earlier period (?) it had a more general meaning, closer to the root of the word, as "thatwhich is put on over."1 Works frequently cited are abbreviatedas follows: Add = L. Burn and R. Glynn, Beazley Addenda,Oxford 1982 Bieber = M. Bieber, History of the Greekand Roman Theater,2nd ed., Princeton 1981 Burn = L. Burn, The Meidias Painter, Oxford 1987 Laskares = N. Laskares, Mop4aL LEpE'(V (X;r'LapXaLov MV7JEfLV?>>, AE?\T 8, 1923 (1925), pp. 103-116 LSAM = F. Sokolowski,Lois sacre'esde l'Asie Mineure, Paris 1955 LSCG = F. Sokolowski,Lois sacreesdes cite'sgrecques, Paris 1969 LSCG-S = F. Sokolowski,Lois sacre'esdes cite'sgrecques. Supple'ment, Paris 1962 Mantes = A. G. -

Veiling, Αίδώς, and a Red-Figure Amphora by Phintias Author(S): Douglas L

Edinburgh Research Explorer Veiling, , and a Red-Figure Amphora by Phintias Citation for published version: Cairns, D 1996, 'Veiling, , and a Red-Figure Amphora by Phintias', Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. 116, pp. 152-7. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/631962> Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Journal of Hellenic Studies Publisher Rights Statement: © Cairns, D. (1996). Veiling, , and a Red-Figure Amphora by Phintias. Journal of Hellenic Studies, 116, 152-7 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 Veiling, αίδώς, and a Red-Figure Amphora by Phintias Author(s): Douglas L. Cairns Source: The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 116 (1996), pp. 152-158 Published by: The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/631962 . Accessed: 16/12/2013 09:19 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . -

(Eponymous) Heroes

is is a version of an electronic document, part of the series, Dēmos: Clas- sical Athenian Democracy, a publicationpublication ofof e Stoa: a consortium for electronic publication in the humanities [www.stoa.org]. e electronic version of this article off ers contextual information intended to make the study of Athenian democracy more accessible to a wide audience. Please visit the site at http:// www.stoa.org/projects/demos/home. Athenian Political Art from the fi h and fourth centuries: Images of Tribal (Eponymous) Heroes S e Cleisthenic reforms of /, which fi rmly established democracy at Ath- ens, imposed a new division of Attica into ten tribes, each of which consti- tuted a new political and military unit, but included citizens from each of the three geographical regions of Attica – the city, the coast, and the inland. En- rollment in a tribe (according to heredity) was a manda- tory prerequisite for citizenship. As usual in ancient Athenian aff airs, politics and reli- gion came hand in hand and, a er due consultation with Apollo’s oracle at Delphi, each new tribe was assigned to a particular hero a er whom the tribe was named; the ten Amy C. Smith, “Athenian Political Art from the Fi h and Fourth Centuries : Images of Tribal (Eponymous) Heroes,” in C. Blackwell, ed., Dēmos: Classical Athenian Democracy (A.(A. MahoneyMahoney andand R.R. Scaife,Scaife, edd.,edd., e Stoa: a consortium for electronic publication in the humanities [www.stoa.org], . © , A.C. Smith. tribal heroes are thus known as the eponymous (or name giving) heroes. T : Aristotle indicates that each hero already received worship by the time of the Cleisthenic reforms, although little evi- dence as to the nature of the worship of each hero is now known (Aristot. -

Corpvsvasokvm Antiqvorvm

VNION ACADEMIQVE INTERNATIONALE CORPVSVASOKVM ANTIQVORVM RUSSIA POCC145I THE STATE HERMITAGE MUSEUM FOCYLAPCTBEHHLII 3PMHTA)K ST. PETERSBURG CAHKT-HETEPBYPF ATTIC RED-FIGURE DRINKING CUPS by ANNA PETRAKOVA <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER - ROMA RUSSIA - FASCICULE xii THE STATE HERMITAGE MUSEUM - FASCICULE V National Committee Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum Russia Chairpersons Professor MIKHAIL PIOTROVSKY, Director of The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences and the Russian Academy of Arts Dr. IRINA DANILOVA, Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow Committee Members Professor GEORGY VILINBAKHOV, Deputy Director of The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg ANNA TROFIMOVA, Head of the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities, The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg Professor EDuARD FROL0v, Head of the Department of Ancient Greece and Rome, St. Petersburg State University IRINA ANTONOVA, Director of Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow Member of the Russian Academy of Education Professor GEORGY KNABE, Institute of the Humanities, State Humane University of Russia, Moscow Dr. OLGA TUGUSHEVA, Department of the Art and Archaeology of the Ancient World, Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum. Russia. - Roma: <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER. - V.; 32 cm. In testa al front.: Union Academique Internationale. - Tit. parallelo in russo 12: The State Hermitage Museum, St. Peterbsurg. 5. Attic Red-Figure Drinking Cups / by Anna Petrakova. - Roma: <<L'EFJVIA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER, 2007. - 94 P., 17 c. di tav.: ill.; 32 cm. (Tavole segnate: Russia da 540 a 622) ISBN 88-8265-427-3 CDD 21. 738.3820938 1. San Pietroburgo - Museo dell'Ermitage - Cataloghi 2. Vasi antichi - Russia I. -

Epilykos Kalos

EPILYKOS KALOS (PLATES 63 and 64) N TWO EARLIERPAPERS, the writerattempted to identifymembers of prominent Athenian families in the late 6th century using a combinationof kalos names and os- traka.1 In the second of these studies, it was observed that members of the same family occurredin the work of a single vase painter,2whether praised as kalos or named as partici- pant in a scene of athletics or revelry.3The converse,i.e. that the same individual may be namedon vases by painterswho, on the basis of stylistic affinities,should belong to the same workshop,seems also to be true.4The presentpaper tries to demonstrateboth these proposi- tions by linking membersof another importantfamily, the Philaidai, to a circle of painters on whose vases they appear. The starting point is Epilykos, who is named as kalos 19 times in the years ca. 515- 505, 14 of them on vases by a single painter, Skythes.5Of the other 5, 2 are cups by the Pedieus Painter, whom Beazley considered might in fact be Skythes late in the latter's career;61 is a cup linked to Skythes by Bloesch,7 through the potter work, and through details of draughtsmanship,by Beazley;8 1 is a cup placed by Beazley near the Carpenter Painter;9and the last is a plastic aryballos with janiform women's heads, which gives its name to Beazley's Epilykos Class.10 The close relationshipof Epilykos and Skythesis especiallystriking in view of Skythes' small oeuvre, so that the 14 vases praising Epilykos accountfor fully half his total output. -

Red-Figured Pottery from Corinth Plate 64

RED-FIGUREDPOTTERY FROM CORINTH SACRED SPRING AND ELSEWHERE (PLATES 63-74) THE PRESENT ARTICLE publishes the inventoried pieces of Attic red-figured pottery discovered during the excavations of the Sacred Spring. Four fragments, 49-52, belong to an unidentified fabric which does not appear to be Attic. The article also includes fragments from the Peribolos of Apollo and the Lechaion Road East, and ends with two miscellaneous sherds and an importantstemless cup. This is, in fact, the first of two articles which will cover most of the Attic red figure that has been found at Corinth since 1957.1The second article will deal with the pottery from the recent exca- vations in the central and southwesternarea of the Forum. Some 71 pieces, mainly fragments, are presented here: 52 (1-52) come from the Sacred Spring, 6 (53-58) from the Peribolos of Apollo, 10 (59-68) from excavations below Roman Shop V, east of the Lechaion Road, 3 (69-71) from various findspots. The catalogue is arrangedby shape and, within each shape, by date so far as possible. A. SACRED SPRING (Pls. 63-69) The early excavations in the Sacred Spring were published by B. H. Hill. The area was re-examined from 1968 to 1970 and again in 1972, during which eight architectural phases were distinguished, the earliest beginning in the later 8th century, the latest ending with the destruction of Corinth in 146 B.C.2 All the inventoried Attic red figure from the new excavations is listed in the following catalogue, but other fragments, of less significance, are kept in the relevant Corinth pottery lots. -

The Sandal As a Hitting Implement in Athenian Iconography ✉ Yael Young1,2

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00558-z OPEN A painful matter: the sandal as a hitting implement in Athenian iconography ✉ Yael Young1,2 The article examines a series of images on Athenian ceramic vases in which sandals are depicted as a hitting implement. This iconographic motif appears mainly in two contexts: educational scenes, where an adult hits a subordinate, and erotic scenes, where the hitting 1234567890():,; action is almost always performed by males upon female prostitutes. The utilisation of this specific mundane object, rather than equally available others, for these violent acts is explored in light of psychologist James J. Gibson’s term “affordance”, which refers to the potentialities held by an object for a particular set of actions, stemming from its material properties. I suggest that the choice of the sandal is not arbitrary: it supports these aggressors’ desire to cause pain to those of lower status, thereby controlling and humiliating them. The affordances of the sandal, stemming from its shape and material and the inherent potentialities for action, are perceived and exploited by the hitters. Though not designed as a hitting implement, in the hands of these privileged figures in these specific situations, the mundane, ordinary sandal becomes the medium, a social agent, by which their control attains physical embodiment. Thanks to the Athenian vase painters, we are able to register and visualise latent affordances of the sandal that previously lay out of sight. It seems that in the context of Athenian society, the supposed dichotomy between the ordinary usage and the extraordinary violent usage of the sandal collapses. -

Painted and Written References of Potters and Painters to Themselves and Their Colleagues

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Pottery to the people. The producttion, distribution and consumption of decorated pottery in the Greek world in the Archaic period (650-480 BC) Stissi, V.V. Publication date 2002 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Stissi, V. V. (2002). Pottery to the people. The producttion, distribution and consumption of decorated pottery in the Greek world in the Archaic period (650-480 BC). General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:04 Oct 2021 VIII The magic mirror of the workshop: painted and written references of potters and painters to themselves and their colleagues 145 Signatures and pictures of workshops are not the only direct references to themselves which Greek potters and pot-painters have left us. -

Hippokrates Son of Anaxileos, Whose Name Appearson Ostraka of the 480'S (P1

HIPPOKRATESSON OF ANAXILEOS (PLATES 74-76) rT5HREE ATTICBLACK-FIGURED VASES of the penultimatedecade of the 6th century bear the kalos name Hippokrates.1A fragmentaryfourth has PATEEKA, for which Beazley proposed the restoration HIHOKPATEXKAAO.2 The four are as follows: 1. Hydria, London B331. ABV, p. 261, no. 41. P1. 74:a. 2. Neck-amphora,Rugby 11. ABV, p. 321, no. 9. Pls. 75, 76:a. 3. Bilingual amphora, Munich 2302. ABV, p. 294, no. 23 and ARV2, p. 6, no. 1. P1. 76:b. 4. Lekythos fragment, Athens, Akr. ARV2, p. 8. Unpublished. All four seem to belong within a fairly small circle of contemporaryartists. No. 1 is in the manner of the LysippidesPainter, and No. 2 is described by Beazley as "some- what recalling" the same painter.3No. 3 is by Psiax, and No. 4 was connected with Psiax by Beazley on the basis of shape as well as the inscription.Psiax painted two vases for the potter Andokides,4who also collaboratedwith the LysippidesPainter.5 In 1887, F. Studniczka first proposed that Hippokrates should be identified as a member of the Alkmeonid family, son of Megakles II and Agariste, and brother of Kleisthenes the legislator.6He is also known to us as the father of Megakles IV, the victim of the second ostracism, in 486 (AthenaionPoliteia, 22.5). Otherwise, nothing is known of Hippokrates'own career. Studniczka's suggestion has been adopted by all subsequent scholars.7 A second Alkmeonid Hippokrates,active in the same period, is now known from several ostraka I I would like to thank ChristophClairmont, who read a draft of this paper, and the journal's-reader for helpful suggestions. -

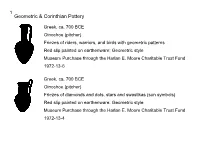

Ancient Mediterranean Gallery Labels

1 Geometric & Corinthian Pottery Greek, ca. 700 BCE Oinochoe (pitcher) Friezes of riders, warriors, and birds with geometric patterns Red slip painted on earthenware; Geometric style Museum Purchase through the Harlan E. Moore Charitable Trust Fund 1972-13-6 Greek, ca. 700 BCE Oinochoe (pitcher) Friezes of diamonds and dots, stars and swastikas (sun symbols) Red slip painted on earthenware; Geometric style Museum Purchase through the Harlan E. Moore Charitable Trust Fund 1972-13-4 2 Geometric & Corinthian Pottery (cont.) Greek, Corinthian, ca. 580 BCE Kotyle (stemless drinking cup) Banded decoration with aquatic birds, panthers, and goats Black and red slip painted on earthenware; “Wild Style” Museum Purchase through the Harlan E. Moore Charitable Trust Fund 1970-9-1 Greek, Corinthian, ca. 600 BCE Olpe (pitcher) Banded decoration of swans, goats, panthers, boars, and sirens Black, red, and white slip painted on earthenware; Moore Painter Museum Purchase through the Harlan E. Moore Charitable Trust Fund 1970-9-2 3 Geometric & Corinthian Pottery (cont.) Greek, Corinthian, ca. 600–590 BCE Oinochoe (pitcher) Banded decoration of owl, sphinx, aquatic bird, panthers, and lions Black, red, and white slip painted on earthenware Museum Purchase through the Harlan E. Moore Charitable Trust Fund 1970-9-4 4 Greek Black-figure Pottery Greek, Attic, ca. 550 BCE Amphora (storage jar) Equestrian scenes Black-figure technique; Pointed Nose Painter (Tyrrhenian group) Museum Purchase through the Harlan E. Moore Charitable Trust Fund 1970-9-3 Greek, Attic, ca. 530–520 BCE Kylix (stemmed drinking cup) Exterior: Apotropaic eyes and Athena battling Giants Interior medallion: Triton Black-figure technique on earthenware; after Exekias Museum Purchase through the Harlan E. -

Fragments of a Cup by the Triptolemos Painter Knauer, Elfriede R Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Fall 1976; 17, 3; Proquest Pg

Fragments of a Cup by the Triptolemos Painter Knauer, Elfriede R Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Fall 1976; 17, 3; ProQuest pg. 209 FOR ADOLF GREIFENHAGEN on his seventieth birthday TEJI.cX')(TJ TWV TOU S,SaCKaAOV f'eyaAWV SEt7TVWV Fragments of a Cup by the Triptolemos Painter Elfriede R. Knauer N THE SEQUENCE of cups by the Triptolemos Painter, Beazley has I placed a sherd in Bryn Mawr next to four fragments in Freiburg with the remark: "Belongs to the Freiburg frr. (no.62) ?"l This fine sherd has recently been published in the first CV-volume of that collection.2 The authors followed Beazley's lead and tried to establish what had become of the fragments in Freiburg, only to learn that they were lost.3 As Beazley had visited Freiburg in 1924 there was reason to expect a photographic record in the archive in Oxford. This was duly found and is here presented for the first time thanks to the generosity of those in charge of that treasure-house." The judicious analysis of the subject on the interior of the Bryn Mawr fragment (PLATE 3 fig. 2b) can be amended by looking at its back (PLATE 5 fig. 2 a b). The authors take the upright object at the left to be a staff. It is the leg of a stool which joins with one of 1 J. D. Beazley, Attic Red-figure Vase-painters 2 (Oxford 1963) [henceforth ARV] 365,63. S CVA U.S.A. 13, The Ella Riegel Memorial Museum, Bryn Mawr College, Attic Red-figured Vases, fasc.l, Ann Harnwell Ashmead and Kyle Meredith Phillips, Jr. -

VII Signatures, Attribution and the Size and Organisation of Workshops

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Pottery to the people. The producttion, distribution and consumption of decorated pottery in the Greek world in the Archaic period (650-480 BC) Stissi, V.V. Publication date 2002 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Stissi, V. V. (2002). Pottery to the people. The producttion, distribution and consumption of decorated pottery in the Greek world in the Archaic period (650-480 BC). General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:04 Oct 2021 VII Signatures, attribution and the size and organisation of workshops 123 VII.1 Signatures, cooperation and specialisation The signatures tell us something about more than only the personal backgrounds of potters and painters, individually or as a group.