The Sandal As a Hitting Implement in Athenian Iconography ✉ Yael Young1,2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Geometric Cemetery on the Areopagus: 1897, 1932, 1947*

A GEOMETRIC CEMETERY ON THE AREOPAGUS: 1897, 1932, 1947* with Appendices on the Geometric Graves found in the Dorpfeld Excavations on the Acropolis West Slope in 1895 and on Hadrian Street ("Phinopoulos' Lot") in 1898 (PLATES 65-80) I. Introduction and the Problem a. The D6rpfeld Excavations p. 325 b. The Agora Excavations and the Search p. 327 c. Disiecta Membra p. 328 II. The Areopagus Cemetery a. General Remarks and Conclusions p. 329 b. Catalogue of Graves and Finds p. 334 Appendix A: Sources for the D6rpfeld Geometric Graves p. 365 Appendix B: The Two Geometric Graves on the Acropolis West Slope: 1895 p. 372 Appendix C: Two Geometric Graves in Phinopoulos' Lot at No. 3, Hadrian Street: 1898 p. 374 Appendix D: A Note on Poulsen's "Akropolisvasen" p. 385 Appendix E: List of Known Finds from the D6rpfeld Geometric Graves p. 387 Appendix F: The Submycenaean Child's Grave South of the Amyneion: 1892 p. 389 I. INTRODUCTION AND THE PROBLEM' A. THE DORPFELD EXCAVATIONS For seven seasons between 1892 and 1899 the German Archaeological Institute, under the general supervision of Wilhelm Dorpfeld, carried out regular excavations in * Professor Penuel P. Kahane died suddenly on February 13, 1974 in Basel. This paper is dedicated to his memory. 1 I am deeply grateful to Professor Homer A. Thompson and to the American School of Classical Studies for the opportunity to study the Agora material; to the German Archaeological Institute in Athens and to Professor Emil Kunze for permission to use the Daybook material; to Dr. Ulf Jantzen for permission to publish the vases in the Institute, and to reproduce the photographs from the Photoabteilung; and to Dr. -

See Attachment

T able of Contents Welcome Address ................................................................................4 Committees ............................................................................................5 10 reasons why you should meet in Athens....................................6 General Information ............................................................................7 Registration............................................................................................11 Abstract Submission ............................................................................12 Social Functions....................................................................................13 Preliminary Scientific Program - Session Topics ..........................14 Preliminary List of Faculty..................................................................15 Hotel Accommodation..........................................................................17 Hotels Description ................................................................................18 Optional Tours........................................................................................21 Pre & Post Congress Tours ................................................................24 Important Dates & Deadlines ............................................................26 3 W elcome Address Dear Colleagues, You are cordially invited to attend the 28th Politzer Society Meeting in Athens. This meeting promises to be one of the world’s largest gatherings of Otologists. -

Stoa Poikile) Built About 475-450 BC

Arrangement Classical Greek cities – either result of continuous growth, or created at a single moment. Former – had streets –lines of communication, curving, bending- ease gradients. Later- had grid plans – straight streets crossing at right angles- ignoring obstacles became stairways where gradients were too steep. Despite these differences, certain features and principles of arrangement are common to both. Greek towns Towns had fixed boundaries. In 6th century BC some were surrounded by fortifications, later became more frequent., but even where there were no walls - demarcation of interior and exterior was clear. In most Greek towns availability of area- devoted to public use rather than private use. Agora- important gathering place – conveniently placed for communication and easily accessible from all directions. The Agora Of Athens • Agora originally meant "gathering place" but came to mean the market place and public square in an ancient Greek city. It was the political, civic, and commercial center of the city, near which were stoas, temples, administrative & public buildings, market places, monuments, shrines etc. • The agora in Athens had private housing, until it was reorganized by Peisistratus in the 6th century BC. • Although he may have lived on the agora himself, he removed the other houses, closed wells, and made it the centre of Athenian government. • He also built a drainage system, fountains and a temple to the Olympian gods. • Cimon later improved the agora by constructing new buildings and planting trees. • In the 5th century BC there were temples constructed to Hephaestus, Zeus and Apollo. • The Areopagus and the assembly of all citizens met elsewhere in Athens, but some public meetings, such as those to discuss ostracism, were held in the agora. -

Corpvsvasokvm Antiqvorvm

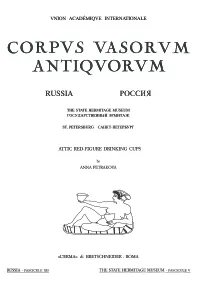

VNION ACADEMIQVE INTERNATIONALE CORPVSVASOKVM ANTIQVORVM RUSSIA POCC145I THE STATE HERMITAGE MUSEUM FOCYLAPCTBEHHLII 3PMHTA)K ST. PETERSBURG CAHKT-HETEPBYPF ATTIC RED-FIGURE DRINKING CUPS by ANNA PETRAKOVA <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER - ROMA RUSSIA - FASCICULE xii THE STATE HERMITAGE MUSEUM - FASCICULE V National Committee Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum Russia Chairpersons Professor MIKHAIL PIOTROVSKY, Director of The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences and the Russian Academy of Arts Dr. IRINA DANILOVA, Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow Committee Members Professor GEORGY VILINBAKHOV, Deputy Director of The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg ANNA TROFIMOVA, Head of the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities, The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg Professor EDuARD FROL0v, Head of the Department of Ancient Greece and Rome, St. Petersburg State University IRINA ANTONOVA, Director of Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow Member of the Russian Academy of Education Professor GEORGY KNABE, Institute of the Humanities, State Humane University of Russia, Moscow Dr. OLGA TUGUSHEVA, Department of the Art and Archaeology of the Ancient World, Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum. Russia. - Roma: <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER. - V.; 32 cm. In testa al front.: Union Academique Internationale. - Tit. parallelo in russo 12: The State Hermitage Museum, St. Peterbsurg. 5. Attic Red-Figure Drinking Cups / by Anna Petrakova. - Roma: <<L'EFJVIA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER, 2007. - 94 P., 17 c. di tav.: ill.; 32 cm. (Tavole segnate: Russia da 540 a 622) ISBN 88-8265-427-3 CDD 21. 738.3820938 1. San Pietroburgo - Museo dell'Ermitage - Cataloghi 2. Vasi antichi - Russia I. -

NEW EOT-English:Layout 1

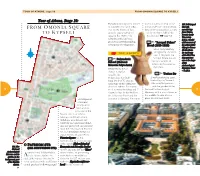

TOUR OF ATHENS, stage 10 FROM OMONIA SQUARE TO KYPSELI Tour of Athens, Stage 10: Papadiamantis Square), former- umental staircases lead to the 107. Bell-shaped FROM MONIA QUARE ly a garden city (with villas, Ionian style four-column propy- idol with O S two-storey blocks of flats, laea of the ground floor, a copy movable legs TO K YPSELI densely vegetated) devel- of the northern hall of the from Thebes, oped in the 1920’s - the Erechteion ( page 13). Boeotia (early 7th century suburban style has been B.C.), a model preserved notwithstanding 1.2 ¢ “Acropol Palace” of the mascot of subsequent development. Hotel (1925-1926) the Athens 2004 Olympic Games A five-story building (In the photo designed by the archi- THE SIGHTS: an exact copy tect I. Mayiasis, the of the idol. You may purchase 1.1 ¢Polytechnic Acropol Palace is a dis- tinctive example of one at the shops School (National Athens Art Nouveau ar- of the Metsovio Polytechnic) Archaeological chitecture. Designed by the ar- Resources Fund – T.A.P.). chitect L. Kaftan - 1.3 tzoglou, the ¢Tositsa Str Polytechnic was built A wide pedestrian zone, from 1861-1876. It is an flanked by the National archetype of the urban tra- Metsovio Polytechnic dition of Athens. It compris- and the garden of the 72 es of a central building and T- National Archaeological 73 shaped wings facing Patision Museum, with a row of trees in Str. It has two floors and the the middle, Tositsa Str is a development, entrance is elevated. Two mon- place to relax and stroll. -

The "Agora" of Pausanias I, 17, 1-2

THE "AGORA" OF PAUSANIAS I, 17, 1-2 P AUSANIAS has given us a long description of the main square of ancient Athens, a place which we are accustomed to call the Agora following Classical Greek usage but which he calls the Kerameikos according to the usage of his own time. This name Kerameikos he uses no less than five times, and in each case it is clear that he is referringto the main square, the ClassicalAgora, of Athens. " There are stoas from the gates to the Kerameikos" he says on entering the city (I, 2, 4), and then, as he begins his description of the square, " the place called Kerameikoshas its name from the hero Keramos-first on the right is the Stoa Basileios as it is called " (I, 3, 1). Farther on he says " above the Kerameikosand the stoa called Basileios is the temple of Hephaistos " (I, 14, 6). Describing Sulla's captureof Athens in 86 B.C. he says that the Roman general shut all the Athenians who had opposed him into the Kerameikos and had one out of each ten of them killed (I, 20, 6). It is generally agreed that this refers to the Classical Agora. Finally, when visiting Mantineia in far-off Arcadia (VII, 9, 8) Pausanias reports seeing ".a copy of the painting in the Kerameikos showing the deeds of the Athenians at Mantineia." The original painting in Athens was in the Stoa of Zeus on the main square, and Pausanias had already described it in his account of Athens (I, 3, 4). -

L Santorini Post Trip

ANCENT GREECE – MYTHS & LEGENDS AND OPEN TO US RESIDENTS A SPECIAL ITINERARY FOR THE WOMEN'S TRAVEL GROUP ROOM SHARES GUARANTEED ON MAIN TRIP 7 Days: Athens, Corinth Canal, Epidaurus, Nafplion, Mycenae, Olympia, Delphi, Aegina, Poros & Hydra + Santorini Tour Overview Nov 7-14 or stay on for Santorini November is mild in Greece. So enjoy this ancient country without the crowds. Our trip starts in Athens with a panoramic tour of the historic landmarks. Next, a guided visit to the Acropolis to see the temple of Athena Nike, the Parthenon, and more. Stops will be made in Peloponneseto see the Corinth canal, Nafplion, and Mycenae. Experience the wonders of the Ancient Olympia Complex, where the original Olympic Games were held. Delphi is next for a day of admiring the amazing sights and learn the history. For the last full day, the tour will transfer to the port of Trokadero for a day cruise to the islands of the Saronic gulf – a day full of adventures that are one of a kind! Day 1 - MON 08 NOV 21: Arrival / Athens (Dinner) Arrive at Athens airport, welcome assistance, and transfer to the hotel. Rest of the day at leisure. In the evening we gather again and after a briefing about our tour, we head at a local restaurant for our welcome dinner. Return transfer to the hotel for overnight. Accommodation: Hotel St. George Lycabettus 5* - 2 Nights Day 2 - TUE 09 NOV 21: Athens city tour / Athens (B,L) The day is dedicated to exploring Athens. Our day begins with a transfer for our guided visit to the Acropolis, including the Propylae, the temple of Athena Nike, the Parthenon, the Erechtheion. -

Ciné Paris Plaka Kidathineon 20

CINÉ PARIS PLAKA KIDATHINEON 20 UPDATED: MAY 2019 Dear Guest, Thank you for choosing Ciné Paris Plaka for your stay in Athens. You have chosen an apartment in the heart of Athens, in the old town of Plaka. In the shadow of the Acropolis and its ancient temples, hillside Plaka has a village feel, with narrow cobblestone streets lined with tiny shops selling jewelry, clothes, local ceramics and souvenirs. Sidewalk cafes and family-run taverns stay open until late, and Cine Paris (next door) shows classic movies al fresco. Nearby, the whitewashed homes of the Anafiotika neighborhood give the small enclave a Greek-island vibe. Following is a small list of recommendations and useful information for you. It is by no means an exhaustive list as there are too many places to eat, drink and sight-see than we could possibly put down. Rather, this is a list of places that we enjoy and that our guests seem to like. We find that our guests like to discover things themselves. After all is that not a great part of the joy of traveling? To discover new experiences and places. We wish you a wonderful stay, and we hope you love Athens! __________________________________________________ The site to purchase tickets online for the Acropolis and slopes, The Temple of Olympian Zeus, Kerameikos, Ancient Agora, Roman Agora, Adrians Library and Aristotle's School is here https://etickets.tap.gr/ Once you access the site in the left-hand corner there are the letters EΛ|EN; click on the EN for English. MUSEUMS THE ACROPOLIS MUSEUM, Dionysiou Areopagitou 15, Athens 117 42 Summer season hours (1/4 – 31/10) Winter season hours (1/11 – 31/3) Monday 8:00 - 16:00 Monday – Thursday 9:00 - 17:00 Tuesday – Sunday 8:00 – 20:00 Friday 9:00 - 22:00 Friday 8:00 a.m. -

Planning Development of Kerameikos up to 35 International Competition 1 Historical and Urban Planning Development of Kerameikos

INTERNATIONAL COMPETITION FOR ARCHITECTS UP TO STUDENT HOUSING 35 HISTORICAL AND URBAN PLANNING DEVELOPMENT OF KERAMEIKOS UP TO 35 INTERNATIONAL COMPETITION 1 HISTORICAL AND URBAN PLANNING DEVELOPMENT OF KERAMEIKOS CONTENTS EARLY ANTIQUITY ......................................................................................................................... p.2-3 CLASSICAL ERA (478-338 BC) .................................................................................................. p.4-5 The municipality of Kerameis POST ANTIQUITY ........................................................................................................................... p.6-7 MIDDLE AGES ................................................................................................................................ p.8-9 RECENT YEARS ........................................................................................................................ p.10-22 A. From the establishment of Athens as capital city of the neo-Greek state until the end of 19th century. I. The first maps of Athens and the urban planning development II. The district of Metaxourgeion • Inclusion of the area in the plan of Kleanthis-Schaubert • The effect of the proposition of Klenze regarding the construction of the palace in Kerameikos • Consequences of the transfer of the palace to Syntagma square • The silk mill factory and the industrialization of the area • The crystallization of the mixed suburban character of the district B. 20th century I. The reformation projects -

Ancient Mediterranean Gallery Labels

1 Geometric & Corinthian Pottery Greek, ca. 700 BCE Oinochoe (pitcher) Friezes of riders, warriors, and birds with geometric patterns Red slip painted on earthenware; Geometric style Museum Purchase through the Harlan E. Moore Charitable Trust Fund 1972-13-6 Greek, ca. 700 BCE Oinochoe (pitcher) Friezes of diamonds and dots, stars and swastikas (sun symbols) Red slip painted on earthenware; Geometric style Museum Purchase through the Harlan E. Moore Charitable Trust Fund 1972-13-4 2 Geometric & Corinthian Pottery (cont.) Greek, Corinthian, ca. 580 BCE Kotyle (stemless drinking cup) Banded decoration with aquatic birds, panthers, and goats Black and red slip painted on earthenware; “Wild Style” Museum Purchase through the Harlan E. Moore Charitable Trust Fund 1970-9-1 Greek, Corinthian, ca. 600 BCE Olpe (pitcher) Banded decoration of swans, goats, panthers, boars, and sirens Black, red, and white slip painted on earthenware; Moore Painter Museum Purchase through the Harlan E. Moore Charitable Trust Fund 1970-9-2 3 Geometric & Corinthian Pottery (cont.) Greek, Corinthian, ca. 600–590 BCE Oinochoe (pitcher) Banded decoration of owl, sphinx, aquatic bird, panthers, and lions Black, red, and white slip painted on earthenware Museum Purchase through the Harlan E. Moore Charitable Trust Fund 1970-9-4 4 Greek Black-figure Pottery Greek, Attic, ca. 550 BCE Amphora (storage jar) Equestrian scenes Black-figure technique; Pointed Nose Painter (Tyrrhenian group) Museum Purchase through the Harlan E. Moore Charitable Trust Fund 1970-9-3 Greek, Attic, ca. 530–520 BCE Kylix (stemmed drinking cup) Exterior: Apotropaic eyes and Athena battling Giants Interior medallion: Triton Black-figure technique on earthenware; after Exekias Museum Purchase through the Harlan E. -

Fragments of a Cup by the Triptolemos Painter Knauer, Elfriede R Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Fall 1976; 17, 3; Proquest Pg

Fragments of a Cup by the Triptolemos Painter Knauer, Elfriede R Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Fall 1976; 17, 3; ProQuest pg. 209 FOR ADOLF GREIFENHAGEN on his seventieth birthday TEJI.cX')(TJ TWV TOU S,SaCKaAOV f'eyaAWV SEt7TVWV Fragments of a Cup by the Triptolemos Painter Elfriede R. Knauer N THE SEQUENCE of cups by the Triptolemos Painter, Beazley has I placed a sherd in Bryn Mawr next to four fragments in Freiburg with the remark: "Belongs to the Freiburg frr. (no.62) ?"l This fine sherd has recently been published in the first CV-volume of that collection.2 The authors followed Beazley's lead and tried to establish what had become of the fragments in Freiburg, only to learn that they were lost.3 As Beazley had visited Freiburg in 1924 there was reason to expect a photographic record in the archive in Oxford. This was duly found and is here presented for the first time thanks to the generosity of those in charge of that treasure-house." The judicious analysis of the subject on the interior of the Bryn Mawr fragment (PLATE 3 fig. 2b) can be amended by looking at its back (PLATE 5 fig. 2 a b). The authors take the upright object at the left to be a staff. It is the leg of a stool which joins with one of 1 J. D. Beazley, Attic Red-figure Vase-painters 2 (Oxford 1963) [henceforth ARV] 365,63. S CVA U.S.A. 13, The Ella Riegel Memorial Museum, Bryn Mawr College, Attic Red-figured Vases, fasc.l, Ann Harnwell Ashmead and Kyle Meredith Phillips, Jr. -

Views of Wealth, a Wealth of Views: Grave Goods in Iron Age Attica

Views of Wealth, a Wealth of Views: Grave Goods in Iron Age Attica Susan Langdon University of Missouri Introduction Connections between women and property in ancient Greece have more often been approached through literary sources than through material remains. Like texts, archaeology presents its own interpretive challenges, and the difficulty of finding pertinent evidence can be compounded by fundamental issues of context and interpretation. Simply identifying certain objects can be problematic. A case in point is the well-known terracotta chest buried ca. 850 BC in the so-called tomb of the Rich Athenian Lady in the Athenian Agora. The lid of the chest carries a set of five model granaries. Out of the ground for thirty-five years, this little masterpiece has figured in discussions of Athenian society, politics, and history. Its prominence in scholarly imagination derives from the suggestion made by its initial commentator, Evelyn Lord Smithson: “If one can put any faith in Aristotle’s statement (Ath. Pol. 3.1) that before Drakon’s time officials were chosen aristinden kai ploutinden [by birth and wealth], property qualifications, however rudimentary, must have existed. Five symbolic measures of grain might have been a boastful reminder that, as everyone knew, the dead lady belonged to the highest propertied class, and that her husband, and surely her father, as a pentakosiomedimnos, had been eligible to serve his community as basileus, polemarch or archon.” The chest, she suggested, symbolized the woman’s dowry.1 Recent studies have thrown cold water on this interpretation from different standpoints.2 As ingenious as it is, the theory rests on modern assumptions regarding politics, social organization, inheritance patterns, mortuary custom, and gender that need individual consideration.