TOPOGRAPHIC SEMANTICS: the Location of the Athenian Public Cemetery and Its Significance for the Nascent Democracy Author(S): Nathan T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Geometric Cemetery on the Areopagus: 1897, 1932, 1947*

A GEOMETRIC CEMETERY ON THE AREOPAGUS: 1897, 1932, 1947* with Appendices on the Geometric Graves found in the Dorpfeld Excavations on the Acropolis West Slope in 1895 and on Hadrian Street ("Phinopoulos' Lot") in 1898 (PLATES 65-80) I. Introduction and the Problem a. The D6rpfeld Excavations p. 325 b. The Agora Excavations and the Search p. 327 c. Disiecta Membra p. 328 II. The Areopagus Cemetery a. General Remarks and Conclusions p. 329 b. Catalogue of Graves and Finds p. 334 Appendix A: Sources for the D6rpfeld Geometric Graves p. 365 Appendix B: The Two Geometric Graves on the Acropolis West Slope: 1895 p. 372 Appendix C: Two Geometric Graves in Phinopoulos' Lot at No. 3, Hadrian Street: 1898 p. 374 Appendix D: A Note on Poulsen's "Akropolisvasen" p. 385 Appendix E: List of Known Finds from the D6rpfeld Geometric Graves p. 387 Appendix F: The Submycenaean Child's Grave South of the Amyneion: 1892 p. 389 I. INTRODUCTION AND THE PROBLEM' A. THE DORPFELD EXCAVATIONS For seven seasons between 1892 and 1899 the German Archaeological Institute, under the general supervision of Wilhelm Dorpfeld, carried out regular excavations in * Professor Penuel P. Kahane died suddenly on February 13, 1974 in Basel. This paper is dedicated to his memory. 1 I am deeply grateful to Professor Homer A. Thompson and to the American School of Classical Studies for the opportunity to study the Agora material; to the German Archaeological Institute in Athens and to Professor Emil Kunze for permission to use the Daybook material; to Dr. Ulf Jantzen for permission to publish the vases in the Institute, and to reproduce the photographs from the Photoabteilung; and to Dr. -

“<> ” Honey Production in Attica, an Antique

“<> ” honey production in Attica, an antique excellence Autor(es): Bossolino, Isabella Publicado por: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra; Annablume URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/39653 DOI: DOI:https://doi.org/10.14195/978-989-26-1191-4_24 Accessed : 4-Oct-2021 14:43:11 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. pombalina.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt Série Diaita Joaquim Pinheiro Scripta & Realia Carmen Soares ISSN: 2183-6523 611907 (coords.) Destina-se esta coleção a publicar textos resultantes da investigação de membros do projeto transnacional DIAITA: Património Alimentar da Lusofonia. As obras consistem 789892 em estudos aprofundados e, na maioria das vezes, de carácter interdisciplinar sobre 9 uma temática fundamental para o desenhar de um património e identidade culturais comuns à população falante da língua portuguesa: a história e as culturas da alimentação. -

See Attachment

T able of Contents Welcome Address ................................................................................4 Committees ............................................................................................5 10 reasons why you should meet in Athens....................................6 General Information ............................................................................7 Registration............................................................................................11 Abstract Submission ............................................................................12 Social Functions....................................................................................13 Preliminary Scientific Program - Session Topics ..........................14 Preliminary List of Faculty..................................................................15 Hotel Accommodation..........................................................................17 Hotels Description ................................................................................18 Optional Tours........................................................................................21 Pre & Post Congress Tours ................................................................24 Important Dates & Deadlines ............................................................26 3 W elcome Address Dear Colleagues, You are cordially invited to attend the 28th Politzer Society Meeting in Athens. This meeting promises to be one of the world’s largest gatherings of Otologists. -

21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECTION Tel.: 2103202049, Fax: 2103226371

LIST OF BANK BRANCHES (BY HEBIC) 30/06/2015 BANK OF GREECE HEBIC BRANCH NAME AREA ADDRESS TELEPHONE NUMBER / FAX 0100001 HEAD OFFICE SECRETARIAT ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECTION tel.: 2103202049, fax: 2103226371 0100002 HEAD OFFICE TENDER AND ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS PROCUREMENT SECTION tel.: 2103203473, fax: 2103231691 0100003 HEAD OFFICE HUMAN ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS RESOURCES SECTION tel.: 2103202090, fax: 2103203961 0100004 HEAD OFFICE DOCUMENT ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS MANAGEMENT SECTION tel.: 2103202198, fax: 2103236954 0100005 HEAD OFFICE PAYROLL ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS MANAGEMENT SECTION tel.: 2103202096, fax: 2103236930 0100007 HEAD OFFICE SECURITY ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECTION tel.: 2103202101, fax: 210 3204059 0100008 HEAD OFFICE SYSTEMIC CREDIT ATHENS CENTRE 3, Amerikis, 102 50 ATHENS INSTITUTIONS SUPERVISION SECTION A tel.: 2103205154, fax: …… 0100009 HEAD OFFICE BOOK ENTRY ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECURITIES MANAGEMENT SECTION tel.: 2103202620, fax: 2103235747 0100010 HEAD OFFICE ARCHIVES ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECTION tel.: 2103202206, fax: 2103203950 0100012 HEAD OFFICE RESERVES ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS MANAGEMENT BACK UP SECTION tel.: 2103203766, fax: 2103220140 0100013 HEAD OFFICE FOREIGN ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS EXCHANGE TRANSACTIONS SECTION tel.: 2103202895, fax: 2103236746 0100014 HEAD OFFICE SYSTEMIC CREDIT ATHENS CENTRE 3, Amerikis, 102 50 ATHENS INSTITUTIONS SUPERVISION SECTION B tel.: 2103205041, fax: …… 0100015 HEAD OFFICE PAYMENT ATHENS CENTRE 3, Amerikis, 102 50 ATHENS SYSTEMS OVERSIGHT SECTION tel.: 2103205073, fax: …… 0100016 HEAD OFFICE ESCB PROJECTS CHALANDRI 341, Mesogeion Ave., 152 31 CHALANDRI AUDIT SECTION tel.: 2106799743, fax: 2106799713 0100017 HEAD OFFICE DOCUMENTARY ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. -

Registration Certificate

1 The following information has been supplied by the Greek Aliens Bureau: It is obligatory for all EU nationals to apply for a “Registration Certificate” (Veveosi Engrafis - Βεβαίωση Εγγραφής) after they have spent 3 months in Greece (Directive 2004/38/EC).This requirement also applies to UK nationals during the transition period. This certificate is open- dated. You only need to renew it if your circumstances change e.g. if you had registered as unemployed and you have now found employment. Below we outline some of the required documents for the most common cases. Please refer to the local Police Authorities for information on the regulations for freelancers, domestic employment and students. You should submit your application and required documents at your local Aliens Police (Tmima Allodapon – Τμήμα Αλλοδαπών, for addresses, contact telephone and opening hours see end); if you live outside Athens go to the local police station closest to your residence. In all cases, original documents and photocopies are required. You should approach the Greek Authorities for detailed information on the documents required or further clarification. Please note that some authorities work by appointment and will request that you book an appointment in advance. Required documents in the case of a working person: 1. Valid passport. 2. Two (2) photos. 3. Applicant’s proof of address [a document containing both the applicant’s name and address e.g. photocopy of the house lease, public utility bill (DEH, OTE, EYDAP) or statement from Tax Office (Tax Return)]. If unavailable please see the requirements for hospitality. 4. Photocopy of employment contract. -

Stoa Poikile) Built About 475-450 BC

Arrangement Classical Greek cities – either result of continuous growth, or created at a single moment. Former – had streets –lines of communication, curving, bending- ease gradients. Later- had grid plans – straight streets crossing at right angles- ignoring obstacles became stairways where gradients were too steep. Despite these differences, certain features and principles of arrangement are common to both. Greek towns Towns had fixed boundaries. In 6th century BC some were surrounded by fortifications, later became more frequent., but even where there were no walls - demarcation of interior and exterior was clear. In most Greek towns availability of area- devoted to public use rather than private use. Agora- important gathering place – conveniently placed for communication and easily accessible from all directions. The Agora Of Athens • Agora originally meant "gathering place" but came to mean the market place and public square in an ancient Greek city. It was the political, civic, and commercial center of the city, near which were stoas, temples, administrative & public buildings, market places, monuments, shrines etc. • The agora in Athens had private housing, until it was reorganized by Peisistratus in the 6th century BC. • Although he may have lived on the agora himself, he removed the other houses, closed wells, and made it the centre of Athenian government. • He also built a drainage system, fountains and a temple to the Olympian gods. • Cimon later improved the agora by constructing new buildings and planting trees. • In the 5th century BC there were temples constructed to Hephaestus, Zeus and Apollo. • The Areopagus and the assembly of all citizens met elsewhere in Athens, but some public meetings, such as those to discuss ostracism, were held in the agora. -

The Parthenon Frieze: Viewed As the Panathenaic Festival Preceding the Battle of Marathon

The Parthenon Frieze: Viewed as the Panathenaic Festival Preceding the Battle of Marathon By Brian A. Sprague Senior Seminar: HST 499 Professor Bau-Hwa Hsieh Western Oregon University Thursday, June 07, 2007 Readers Professor Benedict Lowe Professor Narasingha Sil Copyright © Brian A. Sprague 2007 The Parthenon frieze has been the subject of many debates and the interpretation of it leads to a number of problems: what was the subject of the frieze? What would the frieze have meant to the Athenian audience? The Parthenon scenes have been identified in many different ways: a representation of the Panathenaic festival, a mythical or historical event, or an assertion of Athenian ideology. This paper will examine the Parthenon Frieze in relation to the metopes, pediments, and statues in order to prove the validity of the suggestion that it depicts the Panathenaic festival just preceding the battle of Marathon in 490 BC. The main problems with this topic are that there are no primary sources that document what the Frieze was supposed to mean. The scenes are not specific to any one type of procession. The argument against a Panathenaic festival is that there are soldiers and chariots represented. Possibly that biggest problem with interpreting the Frieze is that part of it is missing and it could be that the piece that is missing ties everything together. The Parthenon may have been the only ancient Greek temple with an exterior sculpture that depicts any kind of religious ritual or service. Because the theme of the frieze is unique we can not turn towards other relief sculpture to help us understand it. -

Parthenon 1 Parthenon

Parthenon 1 Parthenon Parthenon Παρθενών (Greek) The Parthenon Location within Greece Athens central General information Type Greek Temple Architectural style Classical Location Athens, Greece Coordinates 37°58′12.9″N 23°43′20.89″E Current tenants Museum [1] [2] Construction started 447 BC [1] [2] Completed 432 BC Height 13.72 m (45.0 ft) Technical details Size 69.5 by 30.9 m (228 by 101 ft) Other dimensions Cella: 29.8 by 19.2 m (98 by 63 ft) Design and construction Owner Greek government Architect Iktinos, Kallikrates Other designers Phidias (sculptor) The Parthenon (Ancient Greek: Παρθενών) is a temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, dedicated to the Greek goddess Athena, whom the people of Athens considered their patron. Its construction began in 447 BC and was completed in 438 BC, although decorations of the Parthenon continued until 432 BC. It is the most important surviving building of Classical Greece, generally considered to be the culmination of the development of the Doric order. Its decorative sculptures are considered some of the high points of Greek art. The Parthenon is regarded as an Parthenon 2 enduring symbol of Ancient Greece and of Athenian democracy and one of the world's greatest cultural monuments. The Greek Ministry of Culture is currently carrying out a program of selective restoration and reconstruction to ensure the stability of the partially ruined structure.[3] The Parthenon itself replaced an older temple of Athena, which historians call the Pre-Parthenon or Older Parthenon, that was destroyed in the Persian invasion of 480 BC. Like most Greek temples, the Parthenon was used as a treasury. -

NEW EOT-English:Layout 1

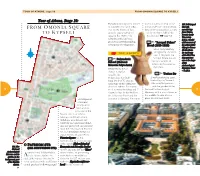

TOUR OF ATHENS, stage 10 FROM OMONIA SQUARE TO KYPSELI Tour of Athens, Stage 10: Papadiamantis Square), former- umental staircases lead to the 107. Bell-shaped FROM MONIA QUARE ly a garden city (with villas, Ionian style four-column propy- idol with O S two-storey blocks of flats, laea of the ground floor, a copy movable legs TO K YPSELI densely vegetated) devel- of the northern hall of the from Thebes, oped in the 1920’s - the Erechteion ( page 13). Boeotia (early 7th century suburban style has been B.C.), a model preserved notwithstanding 1.2 ¢ “Acropol Palace” of the mascot of subsequent development. Hotel (1925-1926) the Athens 2004 Olympic Games A five-story building (In the photo designed by the archi- THE SIGHTS: an exact copy tect I. Mayiasis, the of the idol. You may purchase 1.1 ¢Polytechnic Acropol Palace is a dis- tinctive example of one at the shops School (National Athens Art Nouveau ar- of the Metsovio Polytechnic) Archaeological chitecture. Designed by the ar- Resources Fund – T.A.P.). chitect L. Kaftan - 1.3 tzoglou, the ¢Tositsa Str Polytechnic was built A wide pedestrian zone, from 1861-1876. It is an flanked by the National archetype of the urban tra- Metsovio Polytechnic dition of Athens. It compris- and the garden of the 72 es of a central building and T- National Archaeological 73 shaped wings facing Patision Museum, with a row of trees in Str. It has two floors and the the middle, Tositsa Str is a development, entrance is elevated. Two mon- place to relax and stroll. -

The "Agora" of Pausanias I, 17, 1-2

THE "AGORA" OF PAUSANIAS I, 17, 1-2 P AUSANIAS has given us a long description of the main square of ancient Athens, a place which we are accustomed to call the Agora following Classical Greek usage but which he calls the Kerameikos according to the usage of his own time. This name Kerameikos he uses no less than five times, and in each case it is clear that he is referringto the main square, the ClassicalAgora, of Athens. " There are stoas from the gates to the Kerameikos" he says on entering the city (I, 2, 4), and then, as he begins his description of the square, " the place called Kerameikoshas its name from the hero Keramos-first on the right is the Stoa Basileios as it is called " (I, 3, 1). Farther on he says " above the Kerameikosand the stoa called Basileios is the temple of Hephaistos " (I, 14, 6). Describing Sulla's captureof Athens in 86 B.C. he says that the Roman general shut all the Athenians who had opposed him into the Kerameikos and had one out of each ten of them killed (I, 20, 6). It is generally agreed that this refers to the Classical Agora. Finally, when visiting Mantineia in far-off Arcadia (VII, 9, 8) Pausanias reports seeing ".a copy of the painting in the Kerameikos showing the deeds of the Athenians at Mantineia." The original painting in Athens was in the Stoa of Zeus on the main square, and Pausanias had already described it in his account of Athens (I, 3, 4). -

L Santorini Post Trip

ANCENT GREECE – MYTHS & LEGENDS AND OPEN TO US RESIDENTS A SPECIAL ITINERARY FOR THE WOMEN'S TRAVEL GROUP ROOM SHARES GUARANTEED ON MAIN TRIP 7 Days: Athens, Corinth Canal, Epidaurus, Nafplion, Mycenae, Olympia, Delphi, Aegina, Poros & Hydra + Santorini Tour Overview Nov 7-14 or stay on for Santorini November is mild in Greece. So enjoy this ancient country without the crowds. Our trip starts in Athens with a panoramic tour of the historic landmarks. Next, a guided visit to the Acropolis to see the temple of Athena Nike, the Parthenon, and more. Stops will be made in Peloponneseto see the Corinth canal, Nafplion, and Mycenae. Experience the wonders of the Ancient Olympia Complex, where the original Olympic Games were held. Delphi is next for a day of admiring the amazing sights and learn the history. For the last full day, the tour will transfer to the port of Trokadero for a day cruise to the islands of the Saronic gulf – a day full of adventures that are one of a kind! Day 1 - MON 08 NOV 21: Arrival / Athens (Dinner) Arrive at Athens airport, welcome assistance, and transfer to the hotel. Rest of the day at leisure. In the evening we gather again and after a briefing about our tour, we head at a local restaurant for our welcome dinner. Return transfer to the hotel for overnight. Accommodation: Hotel St. George Lycabettus 5* - 2 Nights Day 2 - TUE 09 NOV 21: Athens city tour / Athens (B,L) The day is dedicated to exploring Athens. Our day begins with a transfer for our guided visit to the Acropolis, including the Propylae, the temple of Athena Nike, the Parthenon, the Erechtheion. -

Cultural Heritage in the Realm of the Commons: Conversations on the Case of Greece

CHAPTER 10 Commoning Over a Cup of Coffee: The Case of Kafeneio, a Co-op Cafe at Plato’s Academy Chrysostomos Galanos The story of Kafeneio Kafeneio, a co-op cafe at Plato’s Academy in Athens, was founded on the 1st of May 2010. The opening day was combined with an open, self-organised gather- ing that emphasised the need to reclaim open public spaces for the people. It is important to note that every turning point in the life of Kafeneio was somehow linked to a large gathering. Indeed, the very start of the initiative, in September 2009, took the form of an alternative festival which we named ‘Point Defect’. In order to understand the choice of ‘Point Defect’ as the name for the launch party, one need only look at the press release we made at the time: ‘When we have a perfect crystal, all atoms are positioned exactly at the points they should be, for the crystal to be intact; in the molecular structure of this crystal everything seems aligned. It can be, however, that one of the atoms is not at place or missing, or another type of atom is at its place. In that case we say that the crystal has a ‘point defect’, a point where its struc- ture is not perfect, a point from which the crystal could start collapsing’. How to cite this book chapter: Galanos, C. 2020. Commoning Over a Cup of Coffee: The Case of Kafeneio, a Co-op Cafe at Plato’s Academy. In Lekakis, S. (ed.) Cultural Heritage in the Realm of the Commons: Conversations on the Case of Greece.