John Goodyear

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Chicago Objects of Veneration

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OBJECTS OF VENERATION: MUSIC AND MATERIALITY IN THE COMPOSER-CULTS OF GERMANY AND AUSTRIA, 1870-1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY ABIGAIL FINE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 © Copyright Abigail Fine 2017 All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES.................................................................. v LIST OF FIGURES.......................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES............................................................................................ ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................. x ABSTRACT....................................................................................................... xiii INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 1: Beethoven’s Death and the Physiognomy of Late Style Introduction..................................................................................................... 41 Part I: Material Reception Beethoven’s (Death) Mask............................................................................. 50 The Cult of the Face........................................................................................ 67 Part II: Musical Reception Musical Physiognomies............................................................................... -

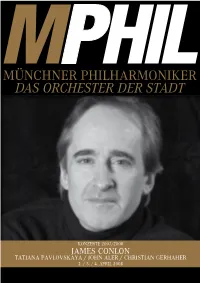

Die Münchner Philharmoniker

Die Münchner Philharmoniker Die Münchner Philharmoniker wurden 1893 auf Privatinitiative von Franz Kaim, Sohn eines Klavierfabrikanten, gegründet und prägen seither das musikalische Leben Münchens. Bereits in den Anfangsjahren des Orchesters – zunächst unter dem Namen »Kaim-Orchester« – garantierten Dirigenten wie Hans Winderstein, Hermann Zumpe und der Bruckner-Schüler Ferdinand Löwe hohes spieltechnisches Niveau und setzten sich intensiv auch für das zeitgenössische Schaffen ein. Von Anbeginn an gehörte zum künstlerischen Konzept auch das Bestreben, durch Programm- und Preisgestaltung allen Bevölkerungs-schichten Zugang zu den Konzerten zu ermöglichen. Mit Felix Weingartner, der das Orchester von 1898 bis 1905 leitete, mehrte sich durch zahlreiche Auslandsreisen auch das internationale Ansehen. Gustav Mahler dirigierte das Orchester in den Jahren 1901 und 1910 bei den Uraufführungen seiner 4. und 8. Symphonie. Im November 1911 gelangte mit dem inzwischen in »Konzertvereins-Orchester« umbenannten Ensemble unter Bruno Walters Leitung Mahlers »Das Lied von der Erde« zur Uraufführung. Von 1908 bis 1914 übernahm Ferdinand Löwe das Orchester erneut. In Anknüpfung an das triumphale Wiener Gastspiel am 1. März 1898 mit Anton Bruckners 5. Symphonie leitete er die ersten großen Bruckner- Konzerte und begründete so die bis heute andauernde Bruckner-Tradition des Orchesters. In die Amtszeit von Siegmund von Hausegger, der dem Orchester von 1920 bis 1938 als Generalmusikdirektor vorstand, fielen u.a. die Uraufführungen zweier Symphonien Bruckners in ihren Originalfassungen sowie die Umbenennung in »Münchner Philharmoniker«. Von 1938 bis zum Sommer 1944 stand der österreichische Dirigent Oswald Kabasta an der Spitze des Orchesters. Eugen Jochum dirigierte das erste Konzert nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg. Mit Hans Rosbaud gewannen die Philharmoniker im Herbst 1945 einen herausragenden Orchesterleiter, der sich zudem leidenschaftlich für neue Musik einsetzte. -

Shattering Fragility: Illness, Suicide, and Refusal in Fin-De-Siècle Viennese Literature

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Shattering Fragility: Illness, Suicide, and Refusal in Fin-De-Siècle Viennese Literature Melanie Jessica Adley University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the German Literature Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Adley, Melanie Jessica, "Shattering Fragility: Illness, Suicide, and Refusal in Fin-De-Siècle Viennese Literature" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 729. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/729 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/729 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shattering Fragility: Illness, Suicide, and Refusal in Fin-De-Siècle Viennese Literature Abstract How fragile is the femme fragile and what does it mean to shatter her fragility? Can there be resistance or even strength in fragility, which would make it, in turn, capable of shattering? I propose that the fragility embodied by young women in fin-de-siècle Vienna harbored an intentionality that signaled refusal. A confluence of factors, including psychoanalysis and hysteria, created spaces for the fragile to find a voice. These bourgeois women occupied a liminal zone between increased access to opportunities, both educational and political, and traditional gender expectations in the home. Although in the late nineteenth century the femme fragile arose as a literary and artistic type who embodied a wan, ethereal beauty marked by delicacy and a passivity that made her more object than authoritative subject, there were signs that illness and suicide could be effectively employed to reject societal mores. -

SLUB Dresden Erwirbt Korrespondenzen Von Clara Schumann Und Johannes Brahms Mit Ernst Rudorff

Berlin, 24. Juni 2021 SLUB Dresden erwirbt Korrespondenzen von Clara Schumann und Johannes Brahms mit Ernst Rudorff Die Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden (SLUB Dresden) erwirbt Korrespondenzen von Clara Schumann (1819-1896) und Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) jeweils mit dem Berliner Dirigenten Ernst Rudorff (1840-1916). Die Korrespondenzen waren bislang für die Wissenschaft unzugänglich. Die Kulturstiftung der Länder fördert den Ankauf mit 42.500 Euro. Dazu Prof. Dr. Markus Hilgert, Generalsekretär der Kulturstiftung der Länder: „Die Botschaft, dass diese mehr als 400 Schriftstücke, die zuvor in Privatbesitz waren, nun erstmals der Öffentlichkeit und der Wissenschaft zugänglich sind – jetzt bereits online verfügbar auf der Webseite der SLUB Dresden –, dürfte zahlreiche Musikwissenschaftlerinnen und Musikwissenschaftler aus der ganzen Welt dorthin locken. Die wertvollen Korrespondenzen sind nicht nur Zeugnisse von Clara Schumanns ausgedehnter Konzerttätigkeit quer durch den Kontinent. Sie sind auch Dokumente einer Musikepoche und bieten Einblicke in die Musikwelt Europas zwischen 1858 und 1896.“ Eigenhändiger Brief Clara Schumann an Ernst Rudorff, Moskau und Petersburg, April/Mai 1864, SLUB Dresden, Mscr.Dresd.App. 3222A,19 u. 20; Foto: © SLUB Dresden/Ramona Ahlers-Bergner Die Korrespondenzen zwischen Clara Schumann und Ernst Rudorff umfassen 215 handschriftliche Briefe der Pianistin und 170 Briefe ihres einstigen Schülers. Der Briefwechsel zwischen Brahms und Rudorff besteht aus 16 Briefen von Brahms und zwölf Gegenbriefen von Rudorff sowie ein Blatt mit Noten, beschrieben von beiden. Beide Briefwechsel wurden in das niedersächsische Verzeichnis national wertvollen Kulturgutes aufgenommen. Rund sechs Jahre (1844-1850) wohnte Clara Schumann gemeinsam mit ihrem Mann in Dresden. Die angekauften Korrespondenzen Schumanns mit Rudorff beginnen 1858 und enden mit bis dahin hoher Regelmäßigkeit im Jahr ihres Todes, 1896. -

Godowsky6 30/06/2003 11:53 Page 8

225187 bk Godowsky6 30/06/2003 11:53 Page 8 Claudius zugeschriebenen Gedichts. Litanei, Robert Braun gewidmet, nach der DDD In Wohin?, dessen Widmungsträger Sergej Vertonung eines Gedichts von Johann Georg Jacobi, ist Rachmaninow ist, bearbeitet Godowsky das zweite Lied ein Gebet für den Seelenfrieden der Verstorbenen. Das Leopold 8.225187 der Schönen Müllerin, in dem der junge Müllersbursche Originallied und die Transkription sind von einer den Bach hört, dessen sanftes Rauschen, in der Stimmung inneren Friedens durchzogen. Klavierfassung eingefangen, ihn aufzufordern scheint, Godowskys Schubert-Transkriptionen enden mit GODOWSKY seine Reise fortzusetzen, doch wohin? einem Konzertarrangement der Ballettmusik zu Die junge Nonne, David Saperton gewidmet, Rosamunde aus dem Jahr 1923 und der Bearbeitung des basiert auf der Vertonung eines Gedichts von Jacob dritten Moment musical op. 94 von 1922. Schubert Transcriptions Nicolaus Craigher. Die junge Nonne kontrastiert den in der Natur brausenden Sturm mit dem Frieden und Keith Anderson Wohin? • Wiegenlied • Die Forelle • Das Wandern • Passacaglia ewigen Lohn des religiösen Lebens. Deutsche Fassung: Bernd Delfs Konstantin Scherbakov, Piano 8.225187 8 225187 bk Godowsky6 30/06/2003 11:53 Page 2 Leopold Godowsky (1870-1938) für 44 Variationen in der traditionellen barocken Form, Godowsky jede Strophe des Original-Lieds. Piano Music Volume 6: Schubert Transcriptions zu denen u.a. auch eine gelungene Anspielung auf den Das Wandern ist das erste Lied des Zyklus Die Erlkönig zählt. Die Variationen, in denen das Thema in schöne Müllerin, in dem der junge Müllersbursche seine The great Polish-American pianist Leopold Godowsky of Saint-Saëns, Godowsky transcribed for piano his unterschiedlichen Gestalten und Registern zurückkehrt, Wanderung beginnt. -

Ernst Rudorff

Ernst Rudorff (b. Berlin, 18. January 1840 – d. Berlin, 31. December 1916) Symphony no. 2 in G minor, op. 40 Born in Berlin, Ernst Friedrich Karl Rudorff was a German conductor, composer, pianist and teacher whose mother knew Mendelssohn and studied with Karl Friedrich Zelter (notable for founding the Berlin Singakademie, amongst other achievements), while his father was a professor of law. Rudorff’s parents’ home was often visited by German Romantic composers of the day, and he numbered Johann Friedrich Reichardt and Ludwig Tieck among his ancestors. From 1850 he studied piano and composition with Woldemar Bargiel (1828–1897), Clara Schumann’s half-brother, who, having studied at the Leipzig Conservatory prior to Rudorff, became a noted teacher and composer emulating though not copying Robert Schumann’s musical style. From 1852 to 1854 Rudorff studied violin with Louis Ries (1830- 1913), a member of the Ries family of musicians, who settled in London in 1853, and he studied piano for a short while with Clara Schumann in 1858, who added him to her list of lifelong musical friends, a list which included Mendelssohn, Joseph Joachim and Brahms. Subsequently, from 1859 to 1860, Rudorff studied history and theology at the universities of Berlin and Leipzig and music at Leipzig Conservatory from 1859 to 1861, where Ignaz Moscheles (for piano) and Julius Rietz (for composition) were his teachers. He then (from 1861 to 1862) studied privately with Carl Reinecke (1824-1910) – who was in his time well connected to Mendelssohn, the Schumanns and -

R Obert Schum Ann's Piano Concerto in AM Inor, Op. 54

Order Number 0S0T795 Robert Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A Minor, op. 54: A stemmatic analysis of the sources Kang, Mahn-Hee, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1992 U MI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 ROBERT SCHUMANN S PIANO CONCERTO IN A MINOR, OP. 54: A STEMMATIC ANALYSIS OF THE SOURCES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Mahn-Hee Kang, B.M., M.M., M.M. The Ohio State University 1992 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Lois Rosow Charles Atkinson - Adviser Burdette Green School of Music Copyright by Mahn-Hee Kang 1992 In Memory of Malcolm Frager (1935-1991) 11 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the late Malcolm Frager, who not only enthusiastically encouraged me In my research but also gave me access to source materials that were otherwise unavailable or hard to find. He gave me an original exemplar of Carl Relnecke's edition of the concerto, and provided me with photocopies of Schumann's autograph manuscript, the wind parts from the first printed edition, and Clara Schumann's "Instructive edition." Mr. Frager. who was the first to publish information on the textual content of the autograph manuscript, made It possible for me to use his discoveries as a foundation for further research. I am deeply grateful to him for giving me this opportunity. I express sincere appreciation to my adviser Dr. Lois Rosow for her patience, understanding, guidance, and insight throughout the research. -

John Carter ˙ Œ Œ Œ Œ

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles An Orchestral Transcription of Johannes Brahms’s Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 3 in D Minor, op. 108 with an Analysis of Performance Considerations A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts by John Murray Carter 2012 © Copyright by John Murray Carter 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION An Orchestral Transcription of Johannes Brahms’s Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 3 in D Minor, op. 108 with an Analysis of Performance Considerations by John Murray Carter Doctor of Musical Arts University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Neal Stulberg, Chair The objective of this dissertation is to examine the orchestration methods of Johannes Brahms, apply these methods to an orchestral transcription of his Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 3 in D Minor, op. 108, and provide a conductor’s analysis of the transcription. Chapter 1 gives a brief historical background, and discusses reasons for and methods of the project. Chapter 2 examines general aspects of Brahms’s orchestrational style. Chapter 3 addresses the transcription process and its application to the Third Violin Sonata. Chapter 4 explores areas in which a thorough understanding of a work’s compositional and orchestrational structure informs performance practice. Chapter 5 discusses differences in chamber and orchestral music observed during the project. The full score of the transcription is included at the end. ii The dissertation of John Murray Carter is approved. Mark Carlson Gary Gray Elizabeth Upton Neal Stulberg, Committee Chair University of California, Los Angeles 2012 iii Dedicated to my wife Bonnie, who never stopped believing in me. -

Die Bühnenbildentwürfe Im Werk Von Max Slevogt

Die Bühnenbildentwürfe im Werk von Max Slevogt Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie an der Ludwig‐Maximilians‐Universität München vorgelegt von Carola Schenk aus München 2015 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Frank Büttner Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Burcu Dogramaci Datum der mündlichen Prüfung: 29. Juni 2015 1 Inhalt Dank ......................................................................................................................................... 5 1. Einführung ........................................................................................................................ 8 1.1 Einleitung ................................................................................................................. 8 1.2 Literaturbericht ....................................................................................................... 12 2. Theater- und Künstlerszene im ersten Drittel des 20. Jahrhunderts in Berlin ................ 20 2.1 Die Künstlermetropole Berlin ................................................................................ 20 2.2 Die Theatermetropole Berlin .................................................................................. 28 3. Bildende Kunst und Theater – Wechselwirkungen zwischen bildender Kunst und Theater .................................................................................................................................... 35 3.1 Bildende Künstler und das Theater – Maler als Bühnenbildner zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts in Deutschland ............................................................................................. -

The Blue Rider

THE BLUE RIDER 55311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd 1 222.04.132.04.13 111:091:09 2 55311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd 2 222.04.132.04.13 111:091:09 HELMUT FRIEDEL ANNEGRET HOBERG THE BLUE RIDER IN THE LENBACHHAUS, MUNICH PRESTEL Munich London New York 55311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd 3 222.04.132.04.13 111:091:09 55311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd 4 222.04.132.04.13 111:091:09 CONTENTS Preface 7 Helmut Friedel 10 How the Blue Rider Came to the Lenbachhaus Annegret Hoberg 21 The Blue Rider – History and Ideas Plates 75 with commentaries by Annegret Hoberg WASSILY KANDINSKY (1–39) 76 FRANZ MARC (40 – 58) 156 GABRIELE MÜNTER (59–74) 196 AUGUST MACKE (75 – 88) 230 ROBERT DELAUNAY (89 – 90) 260 HEINRICH CAMPENDONK (91–92) 266 ALEXEI JAWLENSKY (93 –106) 272 MARIANNE VON WEREFKIN (107–109) 302 ALBERT BLOCH (110) 310 VLADIMIR BURLIUK (111) 314 ADRIAAN KORTEWEG (112 –113) 318 ALFRED KUBIN (114 –118) 324 PAUL KLEE (119 –132) 336 Bibliography 368 55311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd 5 222.04.132.04.13 111:091:09 55311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd311_5312_Blauer_Reiter_s001-372.indd 6 222.04.132.04.13 111:091:09 PREFACE 7 The Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter), the artists’ group formed by such important fi gures as Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Gabriele Münter, August Macke, Alexei Jawlensky, and Paul Klee, had a momentous and far-reaching impact on the art of the twentieth century not only in the art city Munich, but internationally as well. Their very particular kind of intensely colorful, expressive paint- ing, using a dense formal idiom that was moving toward abstraction, was based on a unique spiritual approach that opened up completely new possibilities for expression, ranging in style from a height- ened realism to abstraction. -

The 1963 Berlin Philharmonie – a Breakthrough Architectural Vision

PRZEGLĄD ZACHODNI I, 2017 BEATA KORNATOWSKA Poznań THE 1963 BERLIN PHILHARMONIE – A BREAKTHROUGH ARCHITECTURAL VISION „I’m convinced that we need (…) an approach that would lead to an interpretation of the far-reaching changes that are happening right in front of us by the means of expression available to modern architecture.1 Walter Gropius The Berlin Philharmonie building opened in October of 1963 and designed by Hans Scharoun has become one of the symbols of both the city and European musical life. Its character and story are inextricably linked with the history of post-war Berlin. Construction was begun thanks to the determination and un- stinting efforts of a citizens initiative – the Friends of the Berliner Philharmo- nie (Gesellschaft der Freunde der Berliner Philharmonie). The competition for a new home for the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (Berliner Philharmonisches Orchester) was won by Hans Scharoun whose design was brave and innovative, tailored to a young republic and democratic society. The path to turn the design into reality, however, was anything but easy. Several years were taken up with political maneuvering, debate on issues such as the optimal location, financing and the suitability of the design which brought into question the traditions of concert halls including the old Philharmonie which was destroyed during bomb- ing raids in January 1944. A little over a year after the beginning of construction the Berlin Wall appeared next to it. Thus, instead of being in the heart of the city, as had been planned, with easy access for residents of the Eastern sector, the Philharmonie found itself on the outskirts of West Berlin in the close vicinity of a symbol of the division of the city and the world. -

JAMES CONLON Hil.De

konzerte 2007/2008 James Conlon www.mphil.de tatiana Pavlovskaya / John aler / Christian Gerhaher 2. / 3. / 4. aPril 2008 Mittwoch, 2. April 2008, 19 Uhr Öffentliche GenerAlprobe DonnerstAG, 3. April 2008, 20 Uhr 5. AbonneMentkonzert G freitAG, 4. April 2008, 20 Uhr 7. AbonneMentkonzert e benjAMin britten „War reqUieM“ op. 66 1. reqUieM AeternAM 2. Dies irAe 3. offertoriUM 4. SanctUs 5. AGnUs Dei 6. liberA Me jAMes conlon DiriGent TatiAnA PavlovskAyA soprAn john Aler tenor christiAn GerhAher bAriton philhArMonischer chor München einstUDierUnG: AnDreAs herrMAnn Tölzer knAbenchor einstUDierUnG: GerhArD schMiDt-GADen konzerte 2007/2008 110. Spielzeit Seit der GründunG 1893 GenerAlMUsikDirektor CHriStiAN THieleMAnn Wolfgang Stähr Der jüngste tag des krieges zu benjamin brittens „war requiem“ op. 66 Benjamin Britten Widmung (1913 – 1976) „in loving memory of roger burney (sub- lieutenant, royal naval volunteer reserve), „War Requiem“ op. 66 piers Dunkerley (captain, royal Marines), David Gill (ordinary seaman, royal navy), 1. requiem aeternam Michael halliday (lieutenant, royal new 2. Dies irae zealand volunteer reserve).“ 3. offertorium 4. sanctus Uraufführung 5. Agnus Dei Am 30. Mai 1962 in der cathedral church 6. libera me of saint Michael in coventry / england (the coventry festival chorus sowie knabenchöre aus leamington und stratford; the city of birmingham symphony orchestra; Dirigen- 2 Lebensdaten des Komponisten ten: Meredith Davies und benjamin britten; Geboren am 22. november 1913 in lowe- Gesangssolisten: heather harper, sopran, stoft / east suffolk; gestorben am 4. Dezem - peter pears, tenor, und Dietrich fischer- ber 1976 in Aldeburgh (Großbritannien). Dieskau, bariton). Entstehung im oktober 1958 erhielt britten den Auftrag des „coventry arts committee“, ein abend- füllendes chorwerk für die einweihung der neuen kathedrale zu schreiben – der vor- gängerbau war zu beginn des zweiten welt- kriegs (am 14./15.