Ernst Rudorff

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FULLTEXT01.Pdf

1 MISSA SOLEMNIS FOR CHOIR, ORGAN, SOLI, PIANO AND CELESTA ANDREAS HALLÉN I. KYRIE 9:23 choir II. GLORIA 15:46 choir, soli SATB III. CREDO 14:07 choir, tenor solo IV. SANCTUS 13:16 choir V. AGNUS DEI 10:06 choir, soli SATB Total playing time: 62:39 Soloists Pia-Karin Helsing, soprano Maria Forsström, alto Conny Thimander, tenor Andreas E. Olsson, bass Lars Nilsson, organ James Jenkins, piano Lars Sjöstedt, celesta 2 The Erik Westberg Vocal Ensemble Soprano Virve Karén (2) Jonatan Brundin (1,2) Linnea Pettersson (1) Olle Sköld (2) Christina Fridolfsson (1,2) Rickard Collin (1) Lotta Kuisma (1,2) Anders Bek (1,2) Alva Stern (1,2) Victoria Stanmore (2) Lars Nilsson, organ Alto James Jenkins, piano Kerstin Eriksson (2) Lars Sjöstedt, celesta Anu Arvola (2) Cecilia Grönfelt (1,2) (1) 11–12 October 2019 Katarina Karlsson (1,2) Kyrie, Sanctus Anna Risberg (1,2) Anna-Karin Lindström (1,2) (2) 28 February–1 March 2020 Gloria, Credo, Agnus Dei Tenor Anders Lundström (1) Anders Eriksson (2) Stefan Millgård (1,2) Adrian Rubin (2) Mattias Lundström (1,2) Örjan Larsson (1,2) Mischa Carlberg (1) Bass Martin Eriksson (1,2) Anders Sturk Steinwall (1) Andreas E. Olsson (1,2) Mikael Sandlund (2) 3 Andreas Hallén © The Music and Theatre Library of Sweden 4 A significant musical pioneer Johan [Johannes1] Andreas Hallén was born on 22 December 1846 in Göteborg (Gothenburg), Sweden. His musical talent was discovered at an early age and he took up playing the piano and later also the organ. As a teenager he set up a music society that gave a very successful concert, inspiring him to invest in becoming a professional musician. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 30,1910-1911, Trip

J ACADEMY OF MUSIC . BROOKLYN Thirtieth Season, 1910-191 MAX FIEDLER, Conductor flrogratron? of % FIRST CONCERT WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE FRIDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 11 AT 8.15 COPYRIGHT, 1910, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER OPERA AMERICA AND ABROAD Mr. H. WINFRED GOFF Frau CLARA WALLENTHIN- Miss EDITH DE LYS London Covent Garden STRANDBERG Stockholm London Covent Garden two seasons America Savage Grand Opera Royal Opera and Dresden Milan Florence Brussels Rome etc. Mrs. CLARA SEXTON- At present singing in Germany Mr. EARL W. MARSHALL CROWLEY Italy Florence Milan Miss LAURA VAN KURAN Italy Florence etc. Barcelona Now singing in America Italy Florence Now in America Now in Italy Mrs. LOUISE HOMER Mr. MYRON W. WHITNEY Mrs. ALICE KRAFT BENSON France Nantes At present with Aborn Grand Opera Co. New York Paris London Brussels Now with Boston singing in New York Metropolitan Opera Co. Lilian Nordica Concert and Opera Chicago Now Co. Italy - Mme. LENA ABARBANELL Miss FANNY B. LOTT Miss BLANCH FOX (VOLPINI) Austria Hungary Germany etc. Italy Palermo Rimini Pisa etc. Italy Venice Milan Vercelli etc. Metropolitan Opera Co. New York Now singing in Italy American Grand Opera Cos. New Nowsinging "Madam Sherry" N.Y. Miss EDITH FROST STEWART York Chicago San Francisco etc. Mr. HENRY GORRELL To create title role in Victor Her- Miss MARY CARSON (KIDD) Italy Florence Genoa Torino etc. bert's new opera " When Sweet Six- Italy Milan etc. Now singing in Italy teen "now rehearsing in New York Now singing in Italy Mr. FLETCHER NORTON Miss BERNICE FISHER Miss ROSINA SIDNA Now singing in New York With the Boston Opera Co. -

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

The University of Chicago Objects of Veneration

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OBJECTS OF VENERATION: MUSIC AND MATERIALITY IN THE COMPOSER-CULTS OF GERMANY AND AUSTRIA, 1870-1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY ABIGAIL FINE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 © Copyright Abigail Fine 2017 All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES.................................................................. v LIST OF FIGURES.......................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES............................................................................................ ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................. x ABSTRACT....................................................................................................... xiii INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 1: Beethoven’s Death and the Physiognomy of Late Style Introduction..................................................................................................... 41 Part I: Material Reception Beethoven’s (Death) Mask............................................................................. 50 The Cult of the Face........................................................................................ 67 Part II: Musical Reception Musical Physiognomies............................................................................... -

A History of the School of Music

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1952 History of the School of Music, Montana State University (1895-1952) John Roswell Cowan The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cowan, John Roswell, "History of the School of Music, Montana State University (1895-1952)" (1952). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2574. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2574 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE TO USERS Page(s) missing in number only; text follows. The manuscript was microfilmed as received. This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI A KCSTOHY OF THE SCHOOL OP MUSIC MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY (1895-1952) by JOHN H. gOWAN, JR. B.M., Montana State University, 1951 Presented In partial fulfillment of the requirements for tiie degree of Master of Music Education MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY 1952 UMI Number EP34848 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction Is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, If material had to be removed, a note will Indicate the deletion. -

SLUB Dresden Erwirbt Korrespondenzen Von Clara Schumann Und Johannes Brahms Mit Ernst Rudorff

Berlin, 24. Juni 2021 SLUB Dresden erwirbt Korrespondenzen von Clara Schumann und Johannes Brahms mit Ernst Rudorff Die Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden (SLUB Dresden) erwirbt Korrespondenzen von Clara Schumann (1819-1896) und Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) jeweils mit dem Berliner Dirigenten Ernst Rudorff (1840-1916). Die Korrespondenzen waren bislang für die Wissenschaft unzugänglich. Die Kulturstiftung der Länder fördert den Ankauf mit 42.500 Euro. Dazu Prof. Dr. Markus Hilgert, Generalsekretär der Kulturstiftung der Länder: „Die Botschaft, dass diese mehr als 400 Schriftstücke, die zuvor in Privatbesitz waren, nun erstmals der Öffentlichkeit und der Wissenschaft zugänglich sind – jetzt bereits online verfügbar auf der Webseite der SLUB Dresden –, dürfte zahlreiche Musikwissenschaftlerinnen und Musikwissenschaftler aus der ganzen Welt dorthin locken. Die wertvollen Korrespondenzen sind nicht nur Zeugnisse von Clara Schumanns ausgedehnter Konzerttätigkeit quer durch den Kontinent. Sie sind auch Dokumente einer Musikepoche und bieten Einblicke in die Musikwelt Europas zwischen 1858 und 1896.“ Eigenhändiger Brief Clara Schumann an Ernst Rudorff, Moskau und Petersburg, April/Mai 1864, SLUB Dresden, Mscr.Dresd.App. 3222A,19 u. 20; Foto: © SLUB Dresden/Ramona Ahlers-Bergner Die Korrespondenzen zwischen Clara Schumann und Ernst Rudorff umfassen 215 handschriftliche Briefe der Pianistin und 170 Briefe ihres einstigen Schülers. Der Briefwechsel zwischen Brahms und Rudorff besteht aus 16 Briefen von Brahms und zwölf Gegenbriefen von Rudorff sowie ein Blatt mit Noten, beschrieben von beiden. Beide Briefwechsel wurden in das niedersächsische Verzeichnis national wertvollen Kulturgutes aufgenommen. Rund sechs Jahre (1844-1850) wohnte Clara Schumann gemeinsam mit ihrem Mann in Dresden. Die angekauften Korrespondenzen Schumanns mit Rudorff beginnen 1858 und enden mit bis dahin hoher Regelmäßigkeit im Jahr ihres Todes, 1896. -

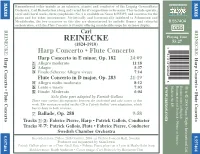

Reinecke Has a Long and Varied List of Compositions to His Name

NAXOS NAXOS Remembered today mainly as an educator, pianist and conductor of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Carl Reinecke has a long and varied list of compositions to his name. They include operatic, vocal and choral works, three symphonies (No. 1 is available on Naxos 8.555397) and concertos for the piano and for other instruments. Stylistically and harmonically indebted to Schumann and Mendelssohn, the two concertos on this disc are characterised by melodic fluency and colourful 8.557404 orchestration, with the Flute Concerto in D major offering considerable scope for virtuoso display. REINECKE: DDD REINECKE: Carl Playing Time REINECKE 55:27 (1824-1910) Harp Concerto • Flute Concerto Harp Concerto • Flute Harp Concerto in E minor, Op. 182 24:09 Harp Concerto • Flute 1 Allegro moderato 11:18 2 Adagio 5:37 3 Finale-Scherzo: Allegro vivace 7:14 Flute Concerto in D major, Op. 283 21:19 4 Allegro molto moderato 8:12 5 Lento e mesto 7:03 www.naxos.com Made in the EU Kommentar auf Deutsch • Notice en français Booklet notes in English ൿ 6 Finale: Moderato 6:04 & Ꭿ Solo flute part adapted by Patrick Gallois 2006 Naxos Rights International Ltd. There exist various discrepancies between the orchestral and solo scores of this work. The version recorded on this CD is Patrick Gallois’ own adaptation, which has its basis in both versions. 7 Ballade, Op. 288 9:58 Tracks 1-3: Fabrice Pierre, Harp • Patrick Gallois, Conductor Tracks 4-7: Patrick Gallois, Flute • Fabrice Pierre, Conductor Swedish Chamber Orchestra 8.557404 8.557404 Recorded from 25th to 28th October, 2004, at Örebro Concert Hall, Sweden. -

Carl Heinrich Carsten Reinecke, Born on 23 June in Altona, Gestorben Am 10

Carl Heinrich Carsten Reinecke, geboren am 23. Juni 1824 Carl Heinrich Carsten Reinecke, born on 23 June in Altona, gestorben am 10. März 1910 in Leipzig, zählt 1824 in Altona, died on 10 March 1910 in Leipzig, zu jenen Gestalten der deutschen Romantik, welche gleich is one of those figures of German romanticism who mehrere Epochen der Musikgeschichte durchlebten, ohne lived through several music historical epochs with- sich von den neuen Strömungen beeinflussen zu lassen. out being in any way influenced by the new tenden- Mitten in die Frühromantik hineingeboren, konnte er die cies. Born in the early romantic era, he experienced schöpferische Laufbahn von so gegensätzlichen Tempera- the creative careers of such opposite personalities as menten wie Chopin und Schumann, Brahms und Liszt Chopin and Schumann, Brahms and Liszt, as well as ebenso mitverfolgen wie die Entwicklung des Virtuosen- the development of the virtuoso and of middle-class tums und der kleinbürgerlichen Salonmusik. salon music. Der von seinem Vater zum Musiker ausgebildete Carl Taught by his father, Carl Reinecke – who never Reinecke, der nie eine Schule besuchte, konzertierte attended school – began by concertizing as a violi- anfänglich als Geiger und Pianist, bevor sein unstetes Leben nist and pianist, before his roving life was brought im Jahre 1860 die wohl entscheidende Wende erfuhr: er to a halt in 1860 by his appointments as director of wurde zum Leiter der Leipziger Gewandhauskonzerte beru- Leipzig’s Gewandhaus concerts and professor at the fen und als Professor ans dortige Konservatorium gewählt. Conservatoire. Prior to this he had travelled extensi- Zuvor war er viel gereist: 1845 hatte er halb Europa durch- vely: in 1845 he toured half of Europe; a year later quert; ein Jahr später war er Hofpianist in Kopenhagen he became court pianist in Copenhagen, where he geworden, wo er mit Niels W. -

CATALOG SUPPLEMENT 2014 Movimentos Edition

CATALOG SUPPLEMENT 2014 Movimentos Edition NEW 2014 Works for Cello and Piano by Richard Strauss, Francis Poulenc, Wolfgang Rihm Benedict Kloeckner, Cello José Gallardo, Piano GEN 14313 Release 2013 Olivier Messiaen: Méditations sur le Mystère de la Sainte Trinité Daniel Beilschmidt, Organ This recording (...) is a program of superlatives in a twofold sense (...) Südwestpresse, May 10, 2013 GEN 13276 Release 2013 Robert Schumann: Fantasiestücke, Op. 12 & Fantasy in C major, Op. 17 Annika Treutler, Piano (...) exceptional musical talent (...) CD tip on hr2-kultur GEN 13272 2 Edition Primavera NEW Tobias Feldmann 2014 Deutscher Musikwettbewerb Award Winner 2012 Tobias Feldmann, Violin Boris Kusnezow, Piano Works by Bartók, Beethoven, Waxman and Ysaÿe GEN 14316 NEW Wassily & Nicolai Gerassimez 2014 Free Fall Deutscher Musikwettbewerb Award Winner 2012 Wassily Gerassimez, Cello Nicolai Gerassimez, Piano Works for Cello and Piano by Mendelssohn Bartholdy, Shostakovich, W. Gerassimez & F. Say GEN 14304 Release 2013 Rie Koyama Deutscher Musikwettbewerb Winner 2010 Rie Koyama, Bassoon Südwestdeutsches Kammerorchester Pforzheim Sebastian Tewinkel, Conductor Bassoon Concertos by Antonio Vivaldi, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, André Jolivet and Paul-Agricole Génin A top flight listening experience. It is sheer pleasure to listen to GEN 13288 the soloist’s performance. CD tip on NDR Kultur Release 2013 Miao Huang Deutscher Musikwettbewerb Award Winner 2011 Miao Huang, Piano Works by Frédéric Chopin and Maurice Ravel (...) yet this is world-class piano playing -

Godowsky6 30/06/2003 11:53 Page 8

225187 bk Godowsky6 30/06/2003 11:53 Page 8 Claudius zugeschriebenen Gedichts. Litanei, Robert Braun gewidmet, nach der DDD In Wohin?, dessen Widmungsträger Sergej Vertonung eines Gedichts von Johann Georg Jacobi, ist Rachmaninow ist, bearbeitet Godowsky das zweite Lied ein Gebet für den Seelenfrieden der Verstorbenen. Das Leopold 8.225187 der Schönen Müllerin, in dem der junge Müllersbursche Originallied und die Transkription sind von einer den Bach hört, dessen sanftes Rauschen, in der Stimmung inneren Friedens durchzogen. Klavierfassung eingefangen, ihn aufzufordern scheint, Godowskys Schubert-Transkriptionen enden mit GODOWSKY seine Reise fortzusetzen, doch wohin? einem Konzertarrangement der Ballettmusik zu Die junge Nonne, David Saperton gewidmet, Rosamunde aus dem Jahr 1923 und der Bearbeitung des basiert auf der Vertonung eines Gedichts von Jacob dritten Moment musical op. 94 von 1922. Schubert Transcriptions Nicolaus Craigher. Die junge Nonne kontrastiert den in der Natur brausenden Sturm mit dem Frieden und Keith Anderson Wohin? • Wiegenlied • Die Forelle • Das Wandern • Passacaglia ewigen Lohn des religiösen Lebens. Deutsche Fassung: Bernd Delfs Konstantin Scherbakov, Piano 8.225187 8 225187 bk Godowsky6 30/06/2003 11:53 Page 2 Leopold Godowsky (1870-1938) für 44 Variationen in der traditionellen barocken Form, Godowsky jede Strophe des Original-Lieds. Piano Music Volume 6: Schubert Transcriptions zu denen u.a. auch eine gelungene Anspielung auf den Das Wandern ist das erste Lied des Zyklus Die Erlkönig zählt. Die Variationen, in denen das Thema in schöne Müllerin, in dem der junge Müllersbursche seine The great Polish-American pianist Leopold Godowsky of Saint-Saëns, Godowsky transcribed for piano his unterschiedlichen Gestalten und Registern zurückkehrt, Wanderung beginnt. -

Woldemar Bargiel (B. Berlin, 3 October 1828 - D

Woldemar Bargiel (b. Berlin, 3 October 1828 - d. Berlin, 23 February 1897) Adagio Op. 38 Preface Woldemar Bargiel enjoyed considerable renown as a composer, conductor, and teacher during his lifetime. Born in Berlin on 3 October 1828, Bargiel benefitted from being a member of a gifted musical family. His father, Adolph Bargiel, was a highly respected piano and voice teacher who taught his son piano, violin, and harmony. Bargiel’s mother, Marianne (née Tromlitz) Wieck, who had divorced Friedrich Wieck in 1824, was the mother of Clara Schumann (née Wieck). In addition to the musical training he received from his parents Bargiel also studied theory with Siegfried Wilhelm Dehn, an eminent teacher, theorist, editor, and librarian. Initial success Bargiel experienced was due in part to Clara. Being nine years older than Bargiel and enjoying a lucrative career as an exceptional concert pianist, Clara’s network of foremost European musicians furthered her brother’s educa- tion and career. Introductions to Felix Mendelssohn and especially to Robert Schumann, who eventually became Bargiel’s brother-in-law, proved crucial. Taking Robert’s advice to enroll at the Leipzig Conservatory in 1846 at the tender age of 16, Bargiel began his extraordinary training. There he studied piano with Ignaz Moscheles and Louis Plaidy; violin with Ferdinand David and Joseph Joachim; and theory and composition with Moritz Hauptmann, Ernst Friedrich Richter, Julius Rietz, and Niels Gade. Upon completion of his studies Bargiel returned to Berlin in 1850. Having quickly developed a favorable reputation as a teacher and composer, some of Bargiel’s early compositions - most notably his first piano trio - were published under the auspices of Clara and Robert Schumann. -

R Obert Schum Ann's Piano Concerto in AM Inor, Op. 54

Order Number 0S0T795 Robert Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A Minor, op. 54: A stemmatic analysis of the sources Kang, Mahn-Hee, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1992 U MI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 ROBERT SCHUMANN S PIANO CONCERTO IN A MINOR, OP. 54: A STEMMATIC ANALYSIS OF THE SOURCES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Mahn-Hee Kang, B.M., M.M., M.M. The Ohio State University 1992 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Lois Rosow Charles Atkinson - Adviser Burdette Green School of Music Copyright by Mahn-Hee Kang 1992 In Memory of Malcolm Frager (1935-1991) 11 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the late Malcolm Frager, who not only enthusiastically encouraged me In my research but also gave me access to source materials that were otherwise unavailable or hard to find. He gave me an original exemplar of Carl Relnecke's edition of the concerto, and provided me with photocopies of Schumann's autograph manuscript, the wind parts from the first printed edition, and Clara Schumann's "Instructive edition." Mr. Frager. who was the first to publish information on the textual content of the autograph manuscript, made It possible for me to use his discoveries as a foundation for further research. I am deeply grateful to him for giving me this opportunity. I express sincere appreciation to my adviser Dr. Lois Rosow for her patience, understanding, guidance, and insight throughout the research.