Preparing for and Responding to Bioterrorism Tularemia and Viral

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amerithrax Investigative Summary

The United States Department of Justice AMERITHRAX INVESTIGATIVE SUMMARY Released Pursuant to the Freedom of Information Act Friday, February 19, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. THE ANTHRAX LETTER ATTACKS . .1 II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . 4 A. Overview of the Amerithrax Investigation . .4 B. The Elimination of Dr. Steven J. Hatfill as a Suspect . .6 C. Summary of the Investigation of Dr. Bruce E. Ivins . 6 D. Summary of Evidence from the Investigation Implicating Dr. Ivins . .8 III. THE AMERITHRAX INVESTIGATION . 11 A. Introduction . .11 B. The Investigation Prior to the Scientific Conclusions in 2007 . 12 1. Early investigation of the letters and envelopes . .12 2. Preliminary scientific testing of the Bacillus anthracis spore powder . .13 3. Early scientific findings and conclusions . .14 4. Continuing investigative efforts . 16 5. Assessing individual suspects . .17 6. Dr. Steven J. Hatfill . .19 7. Simultaneous investigative initiatives . .21 C. The Genetic Analysis . .23 IV. THE EVIDENCE AGAINST DR. BRUCE E. IVINS . 25 A. Introduction . .25 B. Background of Dr. Ivins . .25 C. Opportunity, Access and Ability . 26 1. The creation of RMR-1029 – Dr. Ivins’s flask . .26 2. RMR-1029 is the source of the murder weapon . 28 3. Dr. Ivins’s suspicious lab hours just before each mailing . .29 4. Others with access to RMR-1029 have been ruled out . .33 5. Dr. Ivins’s considerable skill and familiarity with the necessary equipment . 36 D. Motive . .38 1. Dr. Ivins’s life’s work appeared destined for failure, absent an unexpected event . .39 2. Dr. Ivins was being subjected to increasing public criticism for his work . -

2001 Anthrax Letters

Chapter Five: 2001 Anthrax Letters Author’s Note: The analysis and comments regarding the communication efforts described in this case study are solely those of the authors; this analysis does not represent the official position of the FDA. This case was selected because it is one of the few major federal efforts to distribute medical countermeasures in response to an acute biological incident. These events occurred more than a decade ago and represent the early stages of US biosecurity preparedness and response; however, this incident serves as an excellent illustration of the types of communication challenges expected in these scenarios. Due in part to the extended time since these events and the limited accessibility of individual communications and messages, this case study does not provide a comprehensive assessment of all communication efforts. In contrast to the previous case studies in this casebook, the FDA’s role in the 2001 anthrax response was relatively small, and as such, this analysis focuses principally on the communication efforts of the CDC and state and local public health agencies. The 2001 anthrax attacks have been studied extensively, and the myriad of internal and external assessments led to numerous changes to response and communications policies and protocols. The authors intend to use this case study as a means of highlighting communication challenges strictly within the context of this incident, not to evaluate the success or merit of changes made as a result of these events. Abstract The dissemination of Bacillus anthracis via the US Postal Service (USPS) in 2001 represented a new public health threat, the first intentional exposure to anthrax in the United States. -

Lessons from the Anthrax Attacks Implications for US

Lessons from the Anthrax Attacks Implications for US. Bioterrorism Preparedness A Report on a National Forum on Biodefense Author David Heymart Research Assistants Srusha Ac h terb erg, L Joelle Laszld Organized by the Center for Strategic and International Studies and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency --CFr”V? --.....a DlSTRf BUTION This report ISfor official use only; distribution authorized to U S. government agencies, designated contractors, and those with an official need Contains information that may be exempt from public release under the Freedom of Information Act. exemption number 2 (5 USC 552); exemption number 3 (’lo USC 130).Approvalof the Defense Threat Reduction Agency prior to public release is requrred Contract Number OTRAM-02-C-0013 For Official Use Only About CSIS For four decades, the Center for Stravgic and Internahonal Studies (CSIS)has been dedicated 10 providing world leaders with strategic insights on-and pohcy solubons tcurrentand emergtng global lssues CSIS IS led by John J Hamre, former L S deputy secretary of defense It is guided by a board of trustees chaired by former U S senator Sam Nunn and consistlng of prominent individuals horn both the public and private sectors The CSIS staff of 190 researchers and support staff focus pnrnardy on three subjecr areas First, CSIS addresses the fuU spectrum of new challenges to national and mternabonal security Second, it maintains resident experts on all of the world's myor geographical regions Third, it IS committed to helping to develop new methods of governance for the global age, to this end, CSIS has programs on technology and pubhc policy, International trade and finance, and energy Headquartered in Washington, D-C ,CSIS IS pnvate, bipartlsan, and tax-exempt CSIS docs not take specific policy positions, accordygly, all views expressed herein should be understood to be solely those ofthe author Spousor. -

Anthrax Reporting and Investigation Guideline

Anthrax Signs and Symptoms depend on the type of infection; all types can cause severe illness: Symptoms • Cutaneous: painless, pruritic papules or vesicles which form black eschars, often surrounded by edema or erythema. Fever and lymphadenopathy may occur. • Ingestion: Oropharyngeal: mucosal lesion in the oral cavity or oropharynx, sore throat, difficulty swallowing, and swelling of neck. Fever, fatigue, shortness of breath, abdominal pain, nausea/vomiting may occur. Gastrointestinal: abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting/diarrhea, abdominal swelling. Fever, fatigue, and headache are common. • Inhalation: Biphasic, presenting with fever, chills, fatigue, followed by cough, chest pain, shortness of breath, nausea/vomiting, abdominal pain, headache, diaphoresis, and altered mental status. Pleural effusion or mediastinal widening on imaging. • Injection: Severe soft tissue infection; no apparent eschar. Fever, shortness of breath, nausea may occur. Occasional meningeal or abdominal involvement. Incubation Usually < 1 week but as long as 60 days for inhalational anthrax Case Clinical criteria: An illness with at least one specific OR two non-specific symptoms and signs classification that are compatible with one of the above 4 types, systemic involvement, or anthrax meningitis; OR death of unknown cause and consistent organ involvement Confirmed: Clinically Probable: Clinically consistent with Suspect: Clinically consistent with isolation, consistent Gram-positive rods, OR positive consistent with positive IHC, 4-fold rise in test from CLIA-accredited laboratory, OR anthrax test ordered antibodies, PCR, or LF MS epi evidence relating to anthrax but no epi evidence Differential Varies by form; mononucleosis, cat-scratch fever, tularemia, plague, sepsis, bacterial or viral diagnosis pneumonia, mycobacterial infection, influenza, hantavirus Treatment Appropriate antibiotics and supportive care; anthrax antitoxin if spores are activated. -

Bioterrorism & Biodefense

Hugh-Jones et al. J Bioterr Biodef 2011, S3 Bioterrorism & Biodefense http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/2157-2526.S3-001 Review Article Open Access The 2001 Attack Anthrax: Key Observations Martin E Hugh-Jones1*, Barbara Hatch Rosenberg2 and Stuart Jacobsen3 1Professor Emeritus, Louisiana State University; Anthrax Moderator, ProMED-mail, USA 2Sloan-Kettering Institute for Cancer Research and State Univ. of NY-Purchase (retired); Scientists Working Group on CBW, Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation, USA 3Technical Consultant Silicon Materials, Dallas, TX,USA Abstract Unresolved scientificquestions, remaining ten years after the anthrax attacks, three years after the FBI accused a dead man of perpetrating the 2001 anthrax attacks singlehandedly, and more than a year since they closed the case without further investigation, indictment or trial, are perpetuating serious concerns that the FBI may have accused the wrong person of carrying out the anthrax attacks. The FBI has not produced concrete evidence on key questions: • Where and how were the anthrax spores in the attack letters prepared? There is no material evidence of where the attack anthrax was made, and no direct evidence that any specific individual made the anthrax, or mailed it. On the basis of a number` of assumptions, the FBI has not scrutinized the most likely laboratories. • How and why did the spore powders acquire the high levels of silicon and tin found in them? The FBI has repeatedly insisted that the powders in the letters contained no additives, but they also claim that they have not been able to reproduce the high silicon content in the powders, and there has been little public mention of the extraordinary presence of tin. -

Gao-15-80, Anthrax

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Requesters December 2014 ANTHRAX Agency Approaches to Validation and Statistical Analyses Could Be Improved GAO-15-80 December 2014 ANTHRAX Agency Approaches to Validation and Statistical Analyses Could Be Improved Highlights of GAO-15-80, a report to congressional requesters Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found In 2001, the FBI investigated an After the 2001 Anthrax attacks, the genetic tests that were conducted by the intentional release of B. anthracis, a Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) four contractors were generally bacterium that causes anthrax, which scientifically verified and validated, and met the FBI’s criteria. However, GAO was identified as the Ames strain. found that the FBI lacked a comprehensive approach—or framework—that could Subsequently, FBI contractors have ensured standardization of the testing process. As a result, each of the developed and validated several contractors developed their tests differently, and one contractor did not conduct genetic tests to analyze B. anthracis verification testing, a key step in determining whether a test will meet a user’s samples for the presence of certain requirements, such as for sensitivity or accuracy. Also, GAO found that the genetic mutations. The FBI had contractors did not develop the level of statistical confidence for interpreting the previously collected and maintained testing results for the validation tests they performed. Responses to future these samples in a repository. incidents could be improved by using a standardized framework for achieving GAO was asked to review the FBI’s minimum performance standards during verification and validation, and by genetic test development process and incorporating statistical analyses when interpreting validation testing results. -

An Examination of the Potential Threat of a State-Sponsored Biological Attack Against the United States: a Study of Policy Implications

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Spring 2019 An Examination of the Potential Threat of a State-Sponsored Biological Attack Against the United States: A Study of Policy Implications Courtney Anne Pfluke Missouri State University, [email protected] As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the American Politics Commons, Defense and Security Studies Commons, Health Policy Commons, Other Immunology and Infectious Disease Commons, and the Other International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pfluke, Courtney Anne, "An Examination of the Potential Threat of a State-Sponsored Biological Attack Against the United States: A Study of Policy Implications" (2019). MSU Graduate Theses. 3342. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3342 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -

The Impact of the 2001 Anthrax Attacks

University of Birmingham BIOTERRORISM POLICY REFORM AND IMPLEMENTATION IN THE UNITED STATES: THE IMPACT OF THE 2001 ANTHRAX ATTACKS Mary Victoria Cieplak April 5, 2013 Candidate for a MPhil in U.S. Intelligence Services American and Canadian Studies College of Arts and Law ID No. CT/AD/1129744 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. C i e p l a k | 2 Abstract The 2001 anthrax attacks on the United States (U.S.) Congress and U.S. media outlets showed the world that a new form of terror has emerged in our modern society. Prior to 2001, bioterrorism and biological warfare had brief mentions in history books, however, since the 2001 anthrax attacks, a new type of security has been a major priority for the U.S. U.S. politicians, public health workers, three levels of law enforcement, and the entire nation were caught off guard. Now that over a decade has passed, it is appropriate to take a closer look at the impact this act of bioterrorism had on the U.S. government’s formation and implementation of new policies and procedures. -

Communicating in a Crisis: Biological Attack

2. Use common sense, practice good hygiene and cleanliness to avoid spreading germs. “Communication before, during People who are potentially exposed should: and after a biological attack will 1. Follow instructions of health care providers and other public health officials. NEWS &TERRORISM 2. Expect to receive medical evaluation and treatment. Be prepared for long lines. If COMMUNICATING IN A CRISIS be a critical element in effectively the disease is contagious, persons exposed may be quarantined. A fact sheet from the National Academies and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security responding to the crisis and help If people become aware of a suspicious substance nearby, they should: ing people to protect themselves 1. Quickly get away. and recover.” 2. Cover their mouths and noses with layers of fabric that can filter the air but still allow breathing. —A Journalist’s Guide to Covering 3. Wash with soap and water. Bioterrorism (Radio and Television News 4. Contact authorities. BIOLOGICAL ATTACK Director’s Foundation, 2004) 5. Watch TV, listen to the radio, or check the Internet for official news and informa- HUMAN PATHOGENS, BIOTOXINS, tion including the signs and symptoms of the disease, if medications or vaccinations AND AGRICULTURAL THREATS are being distributed, and where to seek medical attention if they become sick. 6. Seek emergency medical attention if they become sick. Table 1. Diseases/Agents Listed by the CDC as Potential WHAT IS IT? Bioterror Threats (as of March 2005). The U.S. Department of Medical Treatment Agriculture maintains lists of animal and plant agents of concern. Table 2 lists general medical treatments for several biothreat agents. -

Analysis of Department of Defense Plans and Responses to Three Potential Anthrax Incidents in March 2005

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND mono- graphs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND monographs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Analysis of Department of Defense Plans and Responses to Three Potential Anthrax Incidents in March 2005 Executive Summary Terrence K. Kelly, Terri Tanielian, Bruce W. Don, Melinda Moore, Charles Meade, K. Scott McMahon, John C. Baker, Gary Cecchine, Deanna Weber Prine, Michael A. -

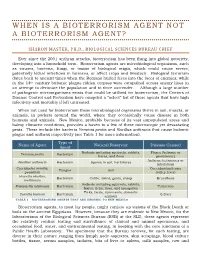

When Is a Bioterrorism Agent Not a Bioterrorism Agent?

WHEN IS A BIOTERRORI SM AGENT NOT A BIOTERRORISM AGENT? SHARON MASTER, PH.D., BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES BUREAU CHIEF Ever since the 2001 anthrax attacks, bioterrorism has been flung into global notoriety, developing into a household term. Bioterrorism agents are microbiological organisms, such as viruses, bacteria, fungi, or toxins of biological origin, which could cause severe, potentially lethal infections in humans, or affect crops and livestock. Biological terrorism dates back to ancient times when the Romans hurled feces into the faces of enemies, while in the 14th century bubonic plague-ridden corpses were catapulted across enemy lines in an attempt to decimate the population and to force surrender. Although a large number of pathogenic microorganisms exists that could be utilized for bioterrorism, the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention have compiled a “select” list of these agents that have high infectivity and mortality if left untreated. When not used for bioterrorism these microbiological organisms thrive in soil, insects, or animals, in pockets around the world, where they occasionally cause disease in both humans and animals. New Mexico, probably because of its vast unpopulated areas and balmy climactic conditions, provides a haven to a few of these microscopic yet devastating pests. These include the bacteria Yersinia pestis and Bacillus anthracis that cause bubonic plague and anthrax respectively (see Table 1 for more information). Type of Name of Agent Natural Reservoir Disease Caused Agent Rodents including squirrels, rabbits, Plague (bubonic or Yersinia pestis Bacterium hares, and fleas pneumonic) Anthrax (cutaneous or Bacillus anthracis Bacterium Spores in soil, herbivores inhalation) Coccidiodes immitis, Coccidioidomycosis Fungus Soil posadasii (valley fever) Brucella abortus, Bacterium Cattle, swine, goats, sheep Brucellosis mellitensis Rodents including squirrels, rabbits, Francisella tularensis Bacterium Tularemia hares, ticks, fleas, and mosquitos Ticks, birds, ruminants, domestic Coxiella burnetti Bacterium Q-fever animals TABLE 1. -

The Policies of Secrecy and Deceit

“BioSecurity”: The Policies of Secrecy and Deceit Meet Homeland Security's New Bioterror Czarina By Tom Burghardt Theme: Biotechnology and GMO Global Research, August 24, 2009 Antifascist Calling... 24 August 2009 In the wake of the 2001 anthrax attacks, successive U.S. administrations have pumped some $57 billion across 11 federal agencies and departments into what is euphemistically called “biodefense.” Never mind that the deadly weaponized pathogen employed in the attacks didn’t originate in some desolate Afghan cave or secret underground bunker controlled by Saddam. And never mind that the principal cheerleaders for expanding state-funded programs are Pentagon bioweaponeers, private corporations and a shadowy nexus of biosecurity apparatchiks who stand to make a bundle under current and future federal initiatives. Leading the charge for increased funding is the Alliance for Biosecurity, a collaborative venture between the Center for Biosecurity of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) and Big Pharma. Speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland in January 2005, former U.S. Senate Majority Leader William Frist, a Bushist acolyte, baldly stated that “The greatest existential threat we have in the world today is biological” and predicted that “an inevitable bioterror attack” would come “at some time in the next 10 years.” Later that year, Frist and former House Speaker Dennis Hastert (R-IL) covertly inserted language into the 2006 Defense Appropriations bill (H.R. 2863) that granted legal immunity to vaccine manufacturers, even in cases of willful misconduct. It was signed into law by President Bush. According toPublic Citizen andThe New York Times, Frist and Hastert benefited financially from their actions; the pair, as well as 41 other congressmen and senators owned as much as $16 million in pharmaceutical stock.SourceWatch revealed that “the Biotechnology Industry Organization (BIO) is purported to be the key author of the language additions.