Bale Hills in Swaledale and Arkengarthdale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Parasite of Red Grouse (Lagopus Lagopus Scoticus)

THE ECOLOGY AND PATHOLOGY OF TRICHOSTRONGYLUS TENUIS (NEMATODA), A PARASITE OF RED GROUSE (LAGOPUS LAGOPUS SCOTICUS) A thesis submitted to the University of Leeds in fulfilment for the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By HAROLD WATSON (B.Sc. University of Newcastle-upon-Tyne) Department of Pure and Applied Biology, The University of Leeds FEBRUARY 198* The red grouse, Lagopus lagopus scoticus I ABSTRACT Trichostrongylus tenuis is a nematode that lives in the caeca of wild red grouse. It causes disease in red grouse and can cause fluctuations in grouse pop ulations. The aim of the work described in this thesis was to study aspects of the ecology of the infective-stage larvae of T.tenuis, and also certain aspects of the pathology and immunology of red grouse and chickens infected with this nematode. The survival of the infective-stage larvae of T.tenuis was found to decrease as temperature increased, at temperatures between 0-30 C? and larvae were susceptible to freezing and desiccation. The lipid reserves of the infective-stage larvae declined as temperature increased and this decline was correlated to a decline in infectivity in the domestic chicken. The occurrence of infective-stage larvae on heather tips at caecal dropping sites was monitored on a moor; most larvae were found during the summer months but very few larvae were recovered in the winter. The number of larvae recovered from the heather showed a good correlation with the actual worm burdens recorded in young grouse when related to food intake. Examination of the heather leaflets by scanning electron microscopy showed that each leaflet consists of a leaf roll and the infective-stage larvae of T.tenuis migrate into the humid microenvironment' provided by these leaf rolls. -

(""Tfrp Fiwa Dq,Bo

REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD 40 Free House_- Real Ales Bar snacks G^ZETTE _ _ ISSUE NO.212 JANUARY 2014 I - I I No iob roo smor rngr .rtiror., I Books & Maps RLduced rores for Senior I I I citizens I I Tel. 01748 884218 I I Tetephone 07875 253178 | STUBBS ELECTRICAL NORMAN F. BROWN CHARTERED Your Locol Electricol Service SURVEYOR5 & E5TATE A6ENT5 O Rewires/alterations SALES - LETTINGS - MANACEMITN'I' o Showers/storage heaters FREE'NO OBLIGATION' o Fire alarms/emergency lights MARKET APPRAISAL O Underfloor heating AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST O Fault finding 14 Queens Road, Richmond, Norlh Yorkslrirc, DLlO 4AG O Landlords' ceftificates T etz (017 4$ 82247 3 1822967 a PAT Testing www.norrnanfbrown.co.uk o Solar electric Contact Stephen on: T 0t748 822907 M:07980 l30Ol4 E: [email protected] ctrical.co.uk -i_o= ' '-:'' AND v '-: REPAI a, t o f M. - PLUMBING ! GUY J For all your o o plumbing requirements o a AGA'S & RAYBURN'S SERVICED RichardD 5,rnilh ! = Tel: 01748 - 825640 PA NTING & DECOFATING o s. A ghpp7 Al'eru. ta ynu ql.l, ^ To adveftise in the Gazette Quality Local o Vran Tradesmen please S''li;x::^',#* @ FREE NO OBUGIIBLIGATION o6 (rfim npur/J magazinp o contact the editor ! Wurt.k{,qL, FIXEDJD QUOTATIO OTATIONS 01748 88611U505. For { COMPLETEETE DIDECORATING,RATING SERVICE { t (""tfrp fiwa Dq,bo, adveftising rates please AtL APESS; BOTH IilTERNALIA IAL & EXTERUTEXTERI COVERED i o contact the treasurer t48 ! =.f 0L748 824824483 F 01748 884474. Mobile:07932 032501 . Emailr dspaintingl Slurdy,y Hous6 IFarm, ",ilx",""#31?i|lf***Whashton DLl 9 REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD 3 ( lAZlrl'l"l'li MANAGEMENT TEAM REETH & DISTRICT CAZETTE I,TD No material may be reproduced in whole or in part wilhout pcnnission. -

Gunnerside, Swaledale – Conservation Area Character Appraisal

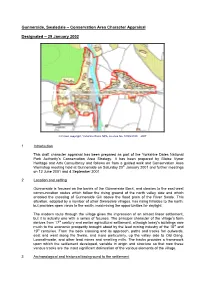

Gunnerside, Swaledale – Conservation Area Character Appraisal Designated – 29 January 2002 © Crown copyright, Yorkshire Dales NPA, Licence No. 100023740 2007 1 Introduction This draft character appraisal has been prepared as part of the Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority’s Conservation Area Strategy. It has been prepared by Blaise Vyner Heritage and Arts Consultancy and follows on from a guided walk and Conservation Area Workshop meeting held at Gunnerside on Saturday 20th January 2001 and further meetings on 12 June 2001 and 4 September 2001. 2 Location and setting Gunnerside is focused on the banks of the Gunnerside Beck, and cleaves to the east-west communication routes which follow the rising ground of the north valley side and which enabled the crossing of Gunnerside Gill above the flood plain of the River Swale. This situation, adopted by a number of other Swaledale villages, has rising hillsides to the north, but provides open views to the south, maximising the opportunities for daylight. The modern route through the village gives the impression of an almost linear settlement, but it is actually one with a series of focuses. The principal character of the village’s form derives from 17th century and earlier agricultural settlement, although today’s buildings owe much to the economic prosperity brought about by the lead mining industry of the 18th and 19th centuries. From the beck crossing and its approach, paths and tracks fan outwards, east and west along the Swale, and more particularly, up the valley side to Old Gang, Lownathwaite, and other lead mines and smelting mills. The tracks provides a framework upon which the settlement developed, variable in origin and structure so that now these various tracks are the most significant delineation of the various elements of the village. -

Swaledale & Arkengarthdale Barns & Walls Conservation Area Appraisal

Swaledale & Arkengarthdale Barns & Walls Conservation Area Appraisal Adopted Document Table of Contents Executive Summary 6 1.0 Introduction 8 1.1 Executive Summary 8 1.2 The Appraisal 8 2.0 Planning Policy Framework 10 2.1 What Is a Conservation Area? 10 2.2 Benefits of Designation 11 3.0 The Special Interest 13 3.1 General 13 3.2 Summary of the Special Interest of the Swaledale & Arkengarthdale Barns & Walls Conservation Area 13 3.3 Summary of Issues Threatening the Special Interest of the Conservation Area 14 9 4.0 Assessing Special Interest 15 4.1 Location and Setting 15 a) Location and Context 15 b) General Character 16 c) Landscape Setting 17 4.2 Historic Development and Archaeology 23 a) Historic Development of the Area 23 b) Archaeology 25 4.3 Spatial Analysis 25 a) Character and Interrelationship of Spaces within the Area 25 b) Key Views and Vistas 26 4.4 Character Analysis 29 a) Definition of Character Zones 29 b) Activity and Prevailing or Former Uses and Their Influence on Plan Form and Buildings 33 c) Quality of Buildings and Their Contribution to the Area 40 d) Audit of Listed Buildings 46 e) Settlements 48 f) Traditional Building Materials, Local Details and the Public Realm 54 g) Contribution Made to the Character of the Area by Green Spaces and Its Biodiversity Value 57 h) Values Attributed by the Local Community and Other Stakeholders 61 i) General Condition of the Swaledale & Arkengarthdale Barns & Walls Conservation Area 62 xx 5.0 Community Involvement 69 6.0 Boundary Changes 70 7.0 Useful Information, Appendices and -

Annales Zoologici Fennici 39: 21-28

ANN. ZOOL. FENNICI Vol. 39 • Breeding losses in red grouse 21 Ann. Zool. Fennici 39: 21–28 ISSN 0003-455X Helsinki 6 March 2002 © Finnish Zoological and Botanical Publishing Board 2002 Breeding losses of red grouse in Glen Esk (NE Scotland): comparative studies, 30 years on Kirsty J. Park1*, Flora Booth2, David Newborn2 & Peter J. Hudson1 1) Department of Biological Sciences, University of Stirling, Stirling FK9 4LA, United Kingdom (*e-mail: [email protected]) 2) Game Conservancy Trust, Swale Farm Satron, Gunnerside, Richmond, North Yorkshire DL8 3HG, United Kingdom Received 5 April 2001, accepted 27 June 2001 Park, K. J., Booth, F., Newborn, D. & Hudson, P. J. 2002: Breeding losses of red grouse in Glen Esk (NE Scotland): comparative studies, 30 years on. — Ann. Zool. Fennici 39: 21–28. Hatching success, brood survival and predation rates of red grouse chicks were examined at four sites in north-east Scotland over two years (1994–1995). Two of these sites have previously been the focus of a large-scale population study on grouse during the late 1950s enabling a comparison to be made. A total of 85 hens were radio-tracked and their breeding success monitored over the two years. Compared with studies undertaken in the 1950s, mean clutch size had risen from 7.2 to 8.6 eggs. Of the 76 nests monitored, 17 (22.4%) broods were lost either through egg or chick predation or by the adult being taken by a predator during incubation. Stoats appeared to be responsible for the largest amount of egg predation. -

Nortr1an F. Browat

Reeth & District Gazett Langthwaite - Arkengi EVOR J. HIRD EREED LI(Onf . prcAt coNTRAcIon FreeHouse-Real/ osmoll --Fnffr estimotes \Jo. Bar Snacks att year. Boo I rotes for Senior citizens lssue: 84 JUI-Y 2002 Tel. 01748 EE42' )hone 01748 886885 vc STUBBS ELECTRICAL LTD ELECTRICAL CONTRACTORS NORtr1AN F. BROWAt/ For all your Domestic & Chartered Surveyors & Estate Agents Commercial Requi rements LEADS THE WAY FORWARD IN ESTATE AGENCY Rewires, Security Lighting, Free market Appraisat withor.rt obtigation - Free tisting on lntemet Showers, Storage Heaters, www. normanfbrown. co. uk Inspections & Testing & Catt now for a professionat Service - Bedate & Richmmd Offices now Portable Appliance Testing. on Intemet for property cietaits with photograph arrC ialout pians Richmond O'ffice : 01748 E22173 | 8229(17 Tef : 01748 822907 Bedate Offke : 01677 42?J287 Fax Ol 748 822345 Letpurn ffiice : 01969 622191 otloz email - stephen@stubbsclectri cal ltdco.u k FREE ESTIMATES V\AMW.OCtipas.COm Pop, Punk, Rock, lndh, R&8, Hig tlop, Jazz, Country, Folk, w Nic erc Soundtracls, and Chlsicrl cd's start fiom f 5,9lll Approved Contractot 04/o1 t-n ail: in foOo(tiprs,com €ffi Tel: 0l 746-884381 Far: 0l 748-88495i w IIIITERE IS ONI,Y ONT] ANVTL SCDf]ARE, RNIXTH CLOCK WORKS TEL : O1748 88476.3 m/ol Clocks & Barometers . Repaired, Cleaned, J. E. HrRD M. GUY PLUMBINC Mobile Eutcher For all your Serviced & Restorecl Prime quality fresh & cooked plumbing requirements Ian Whitruorth meat. Groceries. Weekfy local AGA's & RAYBURN'S visits & Reeth Friday Market SERVICED Dales Centre - Tel: 017683 71709 Rrc Tef : 01748 825640 vc Reeth, Swaledale North Yorkshire. -

Item No. 8 Yorkshire Dales Access Forum – 24 November 2020

Item No. 8 Yorkshire Dales Access Forum – 24 November 2020 Officer’s Report Purpose of the Report The following report brings together, in one place, a collection of items for Members consideration and information. Authority Meetings Any member of the Yorkshire Dales Access Forum can attend Authority Meetings as a member of the public. Please contact Clare Tamea for a copy of the agenda and supporting papers. Please note, it is not a requirement for members of the YDAF to attend Authority meetings, so it is not an ‘approved duty’ and LAF members cannot claim expenses for attending such meetings. Authority Meeting Dates and Venues for 2020/2021: Date Venue Time 15 December 2020 Lifesize virtual meeting 13.00 30 March 2021 TBC 13.00 29 June 2021 TBC 10.30 28 September 2021 TBC 13.00 14 December 2021 TBC 13.00 NB. During the lockdown period meetings have taken place on the Lifesize virtual meeting platform. Please check closer to the time for up to date information. Meetings of the Yorkshire Dales Access Forum for 2021 The following are the dates for meetings during 2021 (venues tbc nearer the time): Tuesday 18 May 2021, 1.15 pm @ Yoredale, Bainbridge Tuesday 23 November 2021, 1.15 pm @ Yoredale, Bainbridge 1 Yorkshire Dales Access Forum Membership Due to Covid 19, the annual application process for membership of the Yorkshire Dales Access Forum has been suspended for this year. Those members that were reaching the end of their three year term have been invited to sit on the forum for a further year, when the recruitment process will be revisited. -

Muker Parish Council Minutes – 2016/17

Muker Parish Council Minutes – 2016/17 22 March 2016 – Annual Meeting 22 March 2106 12 May 2016 16 June 2016 18 August 2016 29 September 2016 3 November 2016 8 December 2016 26 January 2017 MUKER PARISH ANNUAL MEETING The Annual Parish Meeting was held on Tuesday 22 March 2016 at 7.30p.m. in Muker Institute. Councillors Whitehead, Calvert, Porter, Metcalfe, Reynoldson were present. Alison Stringer the Parish Clerk also attended. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE: Cllr Blackie, Cllr Blows ELECTION OF CHAIRMAN: Cllr Ernest Whitehead was elected Chairman, nominated by Cllr Porter and seconded by Cllr Reynoldson. MINUTES OF THE PREVIOUS MEETING: The minutes of the previous meeting held on 17th March, 2015 where read out. The minutes were approved as a correct record. All were in favour. MATTERS ARISING: The notice board in Thwaite has still not got a cork backing – this matter was to be discussed in the Monthly Parish Council meeting following the annual meeting. FINANCIAL STATEMENT AT 31.3.15: This showed an opening balance of £2548.62 Incomings of £7064.04 and Outgoings of £6885.11 The balance to carry forward is £2727.55. All were in favour. ANY OTHER BUSINESS: None MUKER PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES OF PARISH COUNCIL MEETING HELD ON 22 March 2016 The Parish Council meeting was held on the 22nd March 2016. Councillors Calvert, Reynoldson, Metcalfe, Porter, Councillor Whitehead presiding. The Clerk was Miss A Stringer. 1. Apologies for Absence: Cllr John Blackie, Cllr Richard Blows 2. Declaration of Interests: None 3. Minutes of previous meeting: The minutes of the Parish Council meeting held on 16 February 2016 had been circulated. -

Swaledale Museum Newsletter 24 Autumn 2017 Draft

Newsletter No.24 Autumn 2017 Anne Shaw T his year has been, Helen tells me, the best year ever, Hewiit brought probably due to the rain! Rainy days encourage visits to her loom to the indoor attractions, so although we might find the Museum in seemingly endless wet days an irritant (or more), it has September, been good for the Museum. following on from her The talks have been extremely well attended and were inspiring very interesting and varied. I'm not sure how Helen finds exhibition so many excellent speakers but am grateful for her hard ’Land & work in arranging them. Thread’ The exhibition of Anne Hewitt's work has been a great success. Her pieces are so beautiful and I love her blog which shows how she is influenced by the Swaledale Chris Trendell from Canada: ‘I came to get out of the rain - I stayed because I found it most enjoyable.’ countryside around her. I now have one of her cushions, so can admire her skills every day. Chris McLeod from Moray: ‘Shows how good a local history museum can be.’ It is hard to believe that this Museum year has already come to an end but I look forward to welcoming you all Roslyn Docherty from Australia: ‘Remembering my youth back in 2018. in this Sunday School. Loved the visit’. Janet Bishop, Chair Our lively and well attended events suggest we are doing the right thing! We started the Museum year with an art A message from the Curator auction, which was not only tremendous fun, but also raised The most striking thing about this year’s season has been precious funds (£514!). -

Swaledale Museum Newsletter 27 Spring 2019 Draft

Newsletter No.27 Spring 2019 A message from the Curator This year marks the bicentenary of the birth of John Ruskin (1819-1900). Although his prose now reads rather heavily, his ideas are still inspirational. In February I visited the wonderful exhibition on Ruskin at 2 Temple Place in London, and I was struck by how his delight in the ‘Alpine’ air of the countryside of the north-east may perhaps have influenced others. Remember how Marie Hartley and Ella Pontefract describe the ‘Alpine’ views of Swaledale, in their first book published in 1934? Ruskin created a museum in Sheffield, the Guild of St George, in 1870 for the industrial workers of the city. At the same time Swaledale was still very much an Spring has returned to the Museum garden….it must be industrial landscape. Now Ruskin had very clear thoughts on nearly opening time! what a museum should be; a place of learning, interaction and social engagement. In this age of government austerity, which has made such an impact on the funding of culture, perfect shape into which they are fashioned for the infrastructure and education, museums have an even greater function they were meant to follow, and the time taken role to play. even on the most humble object to enhance its aesthetic appeal through decoration. Thinking about the work of 2019 also marks six hundred years since the death of John Ruskin and Leonardo da Vinci makes me look at Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519). It might seem incongruous the our collection in a new and inspiring way, I hope that to connect Ruskin and Leonardo, but both valued the power it will for you also. -

Your Local News Magazine for the Two Dales

REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD ISSUE NO. 200 NOVEMBER 2012 Your local news magazine for the Two Dales FREE YET PRICELESS 2 REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD November Services 2012 4 Nov 9.15 am St. Mary’s Muker Eucharist 10.30 am Low Row URC Reeth Methodist Holy Communion 11.00 am St. Edmund’s, Marske Family Service Holy Trinity Low Row Eucharist Reeth Evangelical Congregational 2.30 pm Gunnerside Methodist 6.00 pm St. Andrew’s Grinton Evening Prayer BCP 6.30 pm Reeth Evangelical Congregational 11 Nov 9.00 am St. Andrew’s Grinton Eucharist St Michael’s Downholme Holy Communion 10.30 am Reeth Methodist Remembrance Service 10.45 am St. Mary’s Arkengarthdale and laying of Wreath St. Mary’s Muker Low Row & Muker Remembrance Service 11.00 am Reeth Evangelical Congregational St. Edmund’s, Marske Morning Service 2.00 pm Keld War Memorial 2.30 pm Arkengarthdale Methodist Holy Communion Remembrance Service 2.45 pm St. Andrew’s Grinton (Parade gathers at Reeth 2 pm) 6.30 pm Reeth Evangelical Congregational 18 Nov 9.15 pm St. Mary’s Muker Eucharist 10.30 am Low Row URC Reeth Methodist Family Service 11.00 am Holy Trinity Low Row Eucharist Reeth Evangelical Congregational St. Edmund’s, Marske Eucharist 2.30 pm Gunnerside Methodist Holy Communion 6.30 pm Reeth Evangelical Congregational 25 Nov 9.30 am St. Andrew’s Grinton Eucharist St Michael’s Downholme Holy Communion 10.30 am Low Row URC Reeth Methodist 11.00 am Reeth Evangelical Congregational St. Edmund’s, Marske Eucharist Crib Service – All families and St. -

Minutes of the Melbecks Parish Council Meeting Held on Thursday July 25Th 2019 at Gunnerside Village Hall

Minutes of the Melbecks Parish Council meeting held on Thursday July 25th 2019 at Gunnerside Village Hall The Melbecks Parish Council meeting was held on Thursday July 25th 2019 at Gunnerside Village Hall. Present were Councillors Silver, Crapper and Lewis with Cllr R. Alderson presiding. The Clerk was Miss N. Adams. 1. Apologies for absence Apologies were received from Cllr McCartney. 2. Declaration of Interests None declared 3. Minutes of the Annual Melbecks Parish Council meeting held on 16th May 2019 The minutes of the Annual Melbecks Parish Council meeting, held on 16th May 2019 were agreed to be a correct record, and these were signed by the Chair. 4. Minutes of the Special meeting held on May 6th 2019 The minutes of the Special Melbecks Parish Council meeting, held on 6th June 2019 were agreed to be a correct record, and these were signed by the Chair. 5. Minutes of the Special meeting held on July 5th 2019 The minutes of the Special Melbecks Parish Council meeting, held on 5th July 2019 were agreed to be a correct record, and these were signed by the Chair. 6. Matters Arising There were no matters arising. 7. Finance There were no finance items. 8. Highways a) 30 mph signs in Low Row. The council noted that 30mph repeater signs have now been installed in Low Row. b) Peat Gate cattle grid. The clerk notified the Council that Highways have added this to their programme of work. c) Brocca Bank. This has also been added to the programme of work. d) Manhole cover in Gunnerside A damaged manhole cover on the road from Gunnerside to Satron has already been notified to Highways, and the clerk was asked to contact Highways to state the council’s support for this work and to try to find out when this work may be taking place.