Annales Zoologici Fennici 39: 21-28

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Parasite of Red Grouse (Lagopus Lagopus Scoticus)

THE ECOLOGY AND PATHOLOGY OF TRICHOSTRONGYLUS TENUIS (NEMATODA), A PARASITE OF RED GROUSE (LAGOPUS LAGOPUS SCOTICUS) A thesis submitted to the University of Leeds in fulfilment for the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By HAROLD WATSON (B.Sc. University of Newcastle-upon-Tyne) Department of Pure and Applied Biology, The University of Leeds FEBRUARY 198* The red grouse, Lagopus lagopus scoticus I ABSTRACT Trichostrongylus tenuis is a nematode that lives in the caeca of wild red grouse. It causes disease in red grouse and can cause fluctuations in grouse pop ulations. The aim of the work described in this thesis was to study aspects of the ecology of the infective-stage larvae of T.tenuis, and also certain aspects of the pathology and immunology of red grouse and chickens infected with this nematode. The survival of the infective-stage larvae of T.tenuis was found to decrease as temperature increased, at temperatures between 0-30 C? and larvae were susceptible to freezing and desiccation. The lipid reserves of the infective-stage larvae declined as temperature increased and this decline was correlated to a decline in infectivity in the domestic chicken. The occurrence of infective-stage larvae on heather tips at caecal dropping sites was monitored on a moor; most larvae were found during the summer months but very few larvae were recovered in the winter. The number of larvae recovered from the heather showed a good correlation with the actual worm burdens recorded in young grouse when related to food intake. Examination of the heather leaflets by scanning electron microscopy showed that each leaflet consists of a leaf roll and the infective-stage larvae of T.tenuis migrate into the humid microenvironment' provided by these leaf rolls. -

North Yorkshire Muker & Swaledale

north yorkshire north yorkshire 19 muker & swaledale 20 rosedale abbey NORTH EAST NORTH uDistance: 7½ miles/12km uTime: 4 hours uGrade: Moderate EAST NORTH uDistance: 6½ miles/10.5km uTime: 4 hours uGrade: Moderate e a blossoming Hawthorn plau N Yo R walK plau N Yo R walK see UR in upper swaledale. EAT F age 60 on p Photo: Photo: dennis kelsall tom bailey tom RoutE RoutE s tart/parking Muker long s tart/parking Considerate stay car park (P&D), DL11 bank Top Farm on the roadside parking in village, 6QG, grid ref sD910978 final stretch of this walk. yo18 8rA, grid ref Is it for me? Mostly good, se724959 well-signed paths and Is it for me? Field and chosen by… see the waterfalls of Kisdon tracks, with a few gentle CHOSEN BY... Start moorland paths and tracks philip thomas Force. Swaledale’s industrial ups & downs. two steeper, DENNis KELSALL 1From the village centre, head stiles 12 Distilling the past emerges as you rise rougher detours to kisdon Rosedale’s abbey past the school and bear R. Yorkshire Dales across opposite bank of the Force & swinner Gill can was, in fact, a priory After 75m, leave L over a stile plaNNiNg be skipped. into half a day’s outing, the river, where exposed paths for nuns, but little remains walking beside a cottage to Nearest town Pickering stiles 2 (& several smaller refreshments the Coach walk from Muker to Keld is a turn into Swinner Gill. Beyond beyond a small turret near the a tarmac drive. Follow it R squeeze stiles/gates) house inn (tel: 01751 heady concoction of flower the ruin of Crackpot Hall, church and a few stones built through a caravan site for 417208); Abbey stores meadows, waterfalls and the ravine is scarred by plaNNiNg into the fabric of the present 300m before the marked tearooms (tel: 01751 drystone workmanship. -

Swaledale Museum Newsletter 29 Spring 2020 Print

Newsletter No.29 Spring 2020 A message from the Curator As I write this, in mid-April, I am hoping that we will be able to resume ‘service as normal’ in the Museum this season. However any forward planning has become an almost impossible task as the situation changes from week to week. Ever the optimist I have decided to assume that we will be re-opening on 21st May and be running our programme of events. However, checking ahead will be paramount as we adapt to the latest guidelines. One of the benefits of the lockdown has been longer and more considered messages between Lidar image of Reeth - thanks to Stephen Eastmead acquaintances. I have, for example, been receiving regular pages from an ‘electronic diary of the plague marginalia in much loved and favourite books. months’ from an elderly friend living in a small hamlet. What sort of evidential trail are we leaving behind He wonderfully captures how small things have acquired us now, that will reflect what the Dale, the country greater meaning and value. I have been reading Jared and the world has gone through? How will curators Diamond’s The World Until Yesterday (2012) in which in the future present these episodes to the public? he compares how traditional and modern societies cope What projects are already in the making to tell the story of how we all reacted and coped? with life, looking at peace and danger, youth and age, language and health. He asks what can we learn from A severe blow to us all has been the loss of Janet ‘traditional’ societies? This spurred me to think about Bishop, Chairman of the Friends of the Museum. -

(""Tfrp Fiwa Dq,Bo

REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD 40 Free House_- Real Ales Bar snacks G^ZETTE _ _ ISSUE NO.212 JANUARY 2014 I - I I No iob roo smor rngr .rtiror., I Books & Maps RLduced rores for Senior I I I citizens I I Tel. 01748 884218 I I Tetephone 07875 253178 | STUBBS ELECTRICAL NORMAN F. BROWN CHARTERED Your Locol Electricol Service SURVEYOR5 & E5TATE A6ENT5 O Rewires/alterations SALES - LETTINGS - MANACEMITN'I' o Showers/storage heaters FREE'NO OBLIGATION' o Fire alarms/emergency lights MARKET APPRAISAL O Underfloor heating AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST O Fault finding 14 Queens Road, Richmond, Norlh Yorkslrirc, DLlO 4AG O Landlords' ceftificates T etz (017 4$ 82247 3 1822967 a PAT Testing www.norrnanfbrown.co.uk o Solar electric Contact Stephen on: T 0t748 822907 M:07980 l30Ol4 E: [email protected] ctrical.co.uk -i_o= ' '-:'' AND v '-: REPAI a, t o f M. - PLUMBING ! GUY J For all your o o plumbing requirements o a AGA'S & RAYBURN'S SERVICED RichardD 5,rnilh ! = Tel: 01748 - 825640 PA NTING & DECOFATING o s. A ghpp7 Al'eru. ta ynu ql.l, ^ To adveftise in the Gazette Quality Local o Vran Tradesmen please S''li;x::^',#* @ FREE NO OBUGIIBLIGATION o6 (rfim npur/J magazinp o contact the editor ! Wurt.k{,qL, FIXEDJD QUOTATIO OTATIONS 01748 88611U505. For { COMPLETEETE DIDECORATING,RATING SERVICE { t (""tfrp fiwa Dq,bo, adveftising rates please AtL APESS; BOTH IilTERNALIA IAL & EXTERUTEXTERI COVERED i o contact the treasurer t48 ! =.f 0L748 824824483 F 01748 884474. Mobile:07932 032501 . Emailr dspaintingl Slurdy,y Hous6 IFarm, ",ilx",""#31?i|lf***Whashton DLl 9 REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD 3 ( lAZlrl'l"l'li MANAGEMENT TEAM REETH & DISTRICT CAZETTE I,TD No material may be reproduced in whole or in part wilhout pcnnission. -

Gunnerside, Swaledale – Conservation Area Character Appraisal

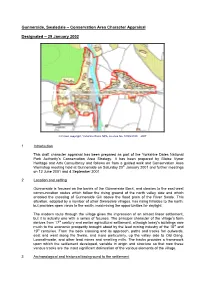

Gunnerside, Swaledale – Conservation Area Character Appraisal Designated – 29 January 2002 © Crown copyright, Yorkshire Dales NPA, Licence No. 100023740 2007 1 Introduction This draft character appraisal has been prepared as part of the Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority’s Conservation Area Strategy. It has been prepared by Blaise Vyner Heritage and Arts Consultancy and follows on from a guided walk and Conservation Area Workshop meeting held at Gunnerside on Saturday 20th January 2001 and further meetings on 12 June 2001 and 4 September 2001. 2 Location and setting Gunnerside is focused on the banks of the Gunnerside Beck, and cleaves to the east-west communication routes which follow the rising ground of the north valley side and which enabled the crossing of Gunnerside Gill above the flood plain of the River Swale. This situation, adopted by a number of other Swaledale villages, has rising hillsides to the north, but provides open views to the south, maximising the opportunities for daylight. The modern route through the village gives the impression of an almost linear settlement, but it is actually one with a series of focuses. The principal character of the village’s form derives from 17th century and earlier agricultural settlement, although today’s buildings owe much to the economic prosperity brought about by the lead mining industry of the 18th and 19th centuries. From the beck crossing and its approach, paths and tracks fan outwards, east and west along the Swale, and more particularly, up the valley side to Old Gang, Lownathwaite, and other lead mines and smelting mills. The tracks provides a framework upon which the settlement developed, variable in origin and structure so that now these various tracks are the most significant delineation of the various elements of the village. -

Your Local News Magazine for the Two Dales

REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD ISSUE NO. 249 MARCH 2017 Your local news magazine for the Two Dales. PRICELESS REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD First Thoughts . Reeth, park up, go for a walk and go home. Not to mention on Fridays when What shall we complain about today? I people drive past the market in Reeth know - cyclists. They’re an easy target. to go to a market elsewhere . oops, What about that bike/running event locals again. they had around Reeth last month. Perhaps we could charge people to What a mess they made of the green! come into Reeth? Just like the Hold on though, this morning I walked bookseller in Hawes who charges 50p across the green and there was some for people who come into his shop and real damage, caused by a large vehicle just browse. He’s popular isn’t he? needlessly driving right across it. These cyclists are a drain on the Locals I suspect - so that’s all right NHS though - especially when they then. come off their bikes and are airlifted These cyclists though, they come to hospital. Never happens to car into Reeth and don’t spend a penny in drivers that. Mind you, I suppose at any of the local businesses. It’s a bit least the cyclists are in the great like on Scott Trial day when there are outdoors, taking exercise and keeping plenty of motor bikes riders coming fit - unlike the thousands of couch through Reeth and not stopping to potatoes who are contributing to a patronise the local businesses; or even diabetes epidemic which threatens to on a weekend when people come into bankrupt the NHS. -

Swaledale and Arkengarthdale

Swaledale and Arkengarthdale Coronavirus support This document is intended to collate all the current information with regard to services available in the two dales to support all residents, particularly those who are self-isolating for whatever reason. An Anchor Hub has been designated by North Yorkshire County Council (NYCC) located at Hudson House in Reeth and managed by Reeth & District Community Transport (RDCT), the Yellow Bus, and Hudson House (HH). This will be managed by Gail Hall and Jill May with the support of the boards of RDCT & HH, and a team of volunteers. Anchor Hub Phone 01748 880 021 manned Monday to Friday 10 am to 3 pm (except bank holidays). Messages can be left at any time. Calls to NYCC from people in the two dales will be redirected to the hub. The hub will maintain a list of contacts in the various communities in the two dales and will direct callers to their nearest support person. The hub will also deliver shopping and prescriptions to your door using the Yellow Bus and volunteers. Village Contacts Anchor Hub Hudson House 01748 880 021 [email protected] or [email protected] Arkengarthdale Susan Dray 01748 884 689 [email protected] Grinton & Ellerton Mark Jones 07710 784 627 [email protected] Gunnerside David Crapper 07814 577 311 [email protected] Healaugh Richard Tarran 07866 410 616 [email protected] Keld Jacqui & Chris 01748 886 374 Melbecks Elizabeth Bedford 01748 886 974 [email protected] (Feetham/Low 07957 207 579 Row/Blades) Delyth Rennie 01748 886 057 [email protected] Muker Jen Gathercole 01748 886 138 [email protected] Jackie Pope 01748 886 414 [email protected] (Prescriptions Hawes Surgery) Reeth Helen Guy 01748 880 212 [email protected] Version 4 final 3 May 2020, 1900 hrs 1 Services by village Arkengarthdale www.arkengarthdale.org.uk A system is in place for delivering bread, milk, eggs and papers; meat; fruit and vegetables; cheese; and plants. -

21. Yorkshire Dales Area Profile: Supporting Documents

National Character 21. Yorkshire Dales Area profile: Supporting documents www.gov.uk/natural-england 1 National Character 21. Yorkshire Dales Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment 1 2 3 White Paper , Biodiversity 2020 and the European Landscape Convention , we North are revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas (NCAs). These are East areas that share similar landscape characteristics, and which follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good Yorkshire decision-making framework for the natural environment. & The North Humber NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform their West decision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The information they contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a landscape East scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage broader Midlands partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will also help West Midlands to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. East of England Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features that shape our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key London drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each area’s characteristics and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental Opportunity (SEOs) are South East suggested, which draw on this integrated information. The SEOs offer guidance South West on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. -

GUNNERSIDE an Introduction to the Built Heritage of the Village

GUNNERSIDE An introduction to the built heritage of the village Gunnerside village stands on the north side of Inn. West of the bridge there is a scatter of The usual 20th-century remodellings and the Swaledale, where the deep ravine of Gunnerside Gill development along and to the south of the Ivelet conversion of even the smallest farm buildings into flows into the main Swale valley. This has long been road, whilst the Methodist Chapel sits on the west of holiday cottages are apparent, especially in the a bridging point on the tributary stream while the the main road. A big chapel (in Swaledale only western part of the village which contains the periodic threat of flooding probably explains why the Reeth has one of comparable size), it is built on a modern school. There were two older church-based present structure spanning the Gill is of no great town rather than a village scale and plan, with twin schools on the east side of the Gill: a Methodist one age. The main road up the valley from Reeth drops stairs from the entrance lobby and galleries all lost to a 20th-century fire (although the attractive down to the bridge, and then turns south along the round. It stands in the centre of an extensive school master’s house survives), and a suitably- west bank of the Gill to cross the Swale and follow graveyard with memorials going back into the Gothic Anglican one - now ‘Gunnarsgill Hall’- looking the south side of the valley up to Muker, whilst a 18th century. -

Yorkshire Swale Flood History 2013

Yorkshire Swale flood history 2013 Sources The greater part of the information for the River Swale comes from a comprehensive PhD thesis by Hugh Bowen Willliams to the University of Leeds in 1957.He in turn has derived his information from newspaper reports, diaries, local topographic descriptions, minutes of Local Authority and Highway Board and, further back in time, from Quarter Sessions bridge accounts. The information is supplemented by various conversations which Williams had with farmers who owned land adjacent to the river. Where possible the height of the flood at the nearest cross- section of the place referred to in the notes is given. This has either been levelled or estimated from the available data. Together with the level above Ordnance Datum (feet) and the section in question there is given (in brackets) the height of the flood above normal water level. Information is also included from the neighbouring dales (mainly Wensleydale and Teesdale) as this gives some indication of conditions in Swaledale. Williams indicates that this is by no means a complete list, but probably contains most of the major floods in the last 200 years, together with some of the smaller ones in the last 70 years. Date and Rainfall Description sources 11 Sep 1673 Spate carried away dwelling house at Brompton-on-Swale. Burnsell Bridge on the Wharfe was washed away. North Riding Selseth Bridge in the Parish of Ranbaldkirke became ruinous by reason of the late great storm. Quarter Sessions (NRQS) ? Jul 1682 Late Brompton Bridge by the late great floods has fallen down. NRQS Speight(1891) Bridge at Brompton-on-Swale was damaged. -

Review of Polling Districts, Polling Places & Polling Stations

Elect ra Elections – polling arrangements Review of polling districts, polling places & polling stations Background information and the Returning Officer’s proposals If you have any comments or questions please contact: Electoral Registration Officer Richmondshire District Council Mercury House Station Road Richmond North Yorkshire DL10 4JX [email protected] or or complete an online survey at www.richmondshire.gov.uk/surveys/polling by 13 September 2019. Polling District and Places Review 2018/2019 Background Within each Local Authority area, legislation requires Councils to carry out reviews of Polling Districts and Polling Places in that area. The Electoral Registration and Administration Act 2013 introduced a change to the timing of compulsory reviews and the next review must be held between 1 October 2018 and 31 January 2020 with subsequent reviews held within a 16 month period starting on 1 October every fifth year after 1 October 2018. The Council’s last review was held in 2013 when a number of minor changes were made. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England (LGBCE) carried out a District Ward Boundary Review and published their final proposals in May 2018. The number of wards reduced from 24 to 16 and took effect at the District Council Elections on 2 May 2019. The majority of our current polling station allocations were not affected by the new Ward Boundary arrangements, however three areas would have been affected. Council at its meeting on 24 July 2018 approved a review of the current polling station allocations for Colburn, Gayles and Richmond parishes as a result of revisions to their parish electoral arrangements. -

Humber River Basin District WFD Investigation

Humber River Basin District WFD Investigation Mining Pollution: Catchment Characterisation Report (up-dated 10 January 2014) Project details Project name Gunnerside Gill catchment characterisation Contact John Barber, GWCL-Yorkshire Area NoCam assessment Probably Not Impacted: Score = 1: Rank = 355 (Eng) River length impacted Gunnerside Gill = 6km downstream of mines Mining Waste Directive inventory Yes (Bunton Lead Mine) Water body summary information Surface Water Body ID GB104027069090 (Humber River Basin District) Surface Water Body Name Gunnerside Gill (Gunnerside Beck) Surface Water Catchment Swale, Ure, Nidd & Upper Ouse (SUNO) Surface Water Body Type Mid, Small, Siliceous (Secondary River) Groundwater Body ID GB40402G701900 (Humber River Basin District) Groundwater Body Name SUNO: Millstone Grit & Carboniferous Limestone RBP Measure in WAP None (Good Status - but see below) RFF Database No Figure 1. Gunnerside Gill location within the Humber River Basin District (in pink) 1 Background information Surface water body classification Status in 2009 Ecological Status Good Biological Status Good General Physico-Chemical Status High Hydromorphological Status Not High Hydromorphological Designation Not a Heavily Modified Water Body Specific Pollutants Overall High Chemical Status Does Not Require Assessment Groundwater body Status Confid Predicted Reason for not classification in 2009 -ence Status achieving good status Disproportionate cost Chemical Status Overall Poor High Good by 2027 Technically infeasible Saline Intrusion Good High Good - Surface Water Impacts Poor Low Good by 2027 Technically infeasible Wetland (GWDTE) Impacts Good Low Good - Drinking Water Protected Area Poor High Good by 2027 Disproportionate cost General Chemical Assessment Poor Low Good by 2027 Technically infeasible Upward Pollutant Trend Yes - - - Figure 2. Gunnerside Gill catchment location 2 Pollution from abandoned metal mines adversely impacts both surface water quality and aqueous ecology with potential reduction in WFD status.