Swaledale Museum Newsletter 27 Spring 2019 Draft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Happy Easter to All from Your Local News Magazine for the Two Dales PRICELESS

REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD ISSUE NO. 193 APRIL 2012 Happy Easter to all from your local news magazine for the Two Dales PRICELESS 2 REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD CHURCH NOTICES in Swaledale & Arkengarthdale st 1 April 9.15 am St. Mary’s Muker Eucharist - Palm Sunday 10.30 am Low Row URC Reeth Methodist 11.00 am Holy Trinity Low Row Eucharist St. Edmund’s Marske Reeth Evangelical Congregational Eucharist 2.00 pm Keld URC 6.00 pm St. Andrew’s, Grinton Evening Prayer BCP 6.30 pm Gunnerside Methodist Reeth Evangelical Congregational th 5 April 7.30 pm Holy Trinity Low Row Eucharist & Watch 8.00 pm St. Michael’s Downholme Vigil th 6 April 9.00 am Keld – Corpse Way Walk - Good Friday 11.00 am Reeth Evangelical Congregational 12.00 pm St Mary’s Arkengarthdale 2.00 pm St. Edmund’s Marske Devotional Service 3.00 pm Reeth Green Meet 2pm Memorial Hall Open Air Witness th 7 April – Easter Eve 8.45 pm St. Andrew’s, Grinton th 8 April 9.15 am St. Mary’s, Muker Eucharist - Easter Sunday 9.30 am St. Andrew’s, Grinton Eucharist St. Michael’s, Downholme Holy Communion 10.30 am Low Row URC Holy Communion Reeth Methodist All Age Service 11.00 am Reeth Evangelical Congregational St. Edmund’s Marske Holy Communion Holy Trinity Low Row Eucharist 11.15 am St Mary’s Arkengarthdale Holy Communion BCP 2.00 pm Keld URC Holy Communion 4.30 pm Reeth Evangelical Congregational Family Service followed by tea 6.30 pm Gunnerside Methodist with Gunnerside Choir Arkengarthdale Methodist Holy Communion th 15 April 9.15 am St. -

Your Local News Magazine for the Two Dales

REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD ISSUE NO. 205 APRIL 2013 Your local news magazine for the Two Dales FREE YET PRICELESS 2 REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD 3 GAZETTE MANAGEMENT TEAM REETH & DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD Chairman: Malcolm Gardner No material may be reproduced in whole Forge House, Healaugh, Richmond DL11 6LD or in part without permission. Whilst Tel/Fax : 01748 884113 every care is taken, the publishers cannot Email : [email protected] be held legally responsible for any errors or opinions in Articles, Listings or Secretary & Upper Dale Distribution: Advertisements. Sue Alderson Published by the Holme View, Low Row, Richmond, DL 11 6PE Reeth & District Gazette Ltd. Tel. : 01748 886292 c/o THE TREASURER Email : [email protected] DAVID TRUSSON Treasurer : David Trusson The Lodge, Marrick Richmond, North Yorkshire. DL11 7LQ The Lodge, Marrick, Richmond, DL11 7LQ Tel./Fax : 01748 884474 Tel. : 01748 884474 Email: [email protected] Email : [email protected] Production Manager: James Alderson “Gazette” - ADVERTISING To ensure prompt attention for new adverts, Greenways, Grinton, Richmond, DL11 6HJ setting up, changes to current advert runs as Tel. : 01748 884312 well as articles for inclusion, please contact: Email :[email protected] The EDITOR - G. M. Lundberg Distribution: Wendy Gardner Gallows Top, Low Row, Richmond, Forge House, Healaugh, Richmond, DL11 6LD North Yorks. DL11 6PP Tel. : 01748 884113 : 01748 886111 or 886505 Email : [email protected] Subscription Secretary : Alex Hewlett, The Vicarage, Reeth, Richmond, DL11 6TR Tel. : 0121 2760040 GAZETTE DEADLINES Email : [email protected] In order that we can distribute the Editor & Advertising Editor: George Lundberg Gazette at the beginning of each Gallows Top, Low Row, Richmond, DL11 6PP month, it is necessary to have a Tel. -

A Parasite of Red Grouse (Lagopus Lagopus Scoticus)

THE ECOLOGY AND PATHOLOGY OF TRICHOSTRONGYLUS TENUIS (NEMATODA), A PARASITE OF RED GROUSE (LAGOPUS LAGOPUS SCOTICUS) A thesis submitted to the University of Leeds in fulfilment for the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By HAROLD WATSON (B.Sc. University of Newcastle-upon-Tyne) Department of Pure and Applied Biology, The University of Leeds FEBRUARY 198* The red grouse, Lagopus lagopus scoticus I ABSTRACT Trichostrongylus tenuis is a nematode that lives in the caeca of wild red grouse. It causes disease in red grouse and can cause fluctuations in grouse pop ulations. The aim of the work described in this thesis was to study aspects of the ecology of the infective-stage larvae of T.tenuis, and also certain aspects of the pathology and immunology of red grouse and chickens infected with this nematode. The survival of the infective-stage larvae of T.tenuis was found to decrease as temperature increased, at temperatures between 0-30 C? and larvae were susceptible to freezing and desiccation. The lipid reserves of the infective-stage larvae declined as temperature increased and this decline was correlated to a decline in infectivity in the domestic chicken. The occurrence of infective-stage larvae on heather tips at caecal dropping sites was monitored on a moor; most larvae were found during the summer months but very few larvae were recovered in the winter. The number of larvae recovered from the heather showed a good correlation with the actual worm burdens recorded in young grouse when related to food intake. Examination of the heather leaflets by scanning electron microscopy showed that each leaflet consists of a leaf roll and the infective-stage larvae of T.tenuis migrate into the humid microenvironment' provided by these leaf rolls. -

Newsletter No.23 Spring 2017

Newsletter No.23 Spring 2017 T here is such a lot to look forward to with the Museum opening at the beginning of May. Helen has put together a very interesting and varied programme of talks, exhibitions and One of the miniature other events so please check them out on the works of art which will back page of this Newsletter and keep an eye be auctioned on May 17th - a local on the local press and the posters at the landscape by Carolyn Museum for changes and additions to the Stephenson programme - everything is also listed on the Museum website of course if you have internet access. The season begins with the AGM on Wednesday 17th May and as usual the official part of the evening will be very short, but followed by a new venture, an auction of art, mostly with local connections, which promises Did our albino mole have any offspring? Will we ever find out more to be great fun. The items to be auctioned will about the little boy who died of diphtheria, whose miniature hob- be on display from 12th May and for those nailed boots were left in a bag outside the Museum after his mother unable to attend on the evening, sealed bids died? Our ‘ferret feeding trough’ seems to have been recycled from a may be left in advance at the Museum. fine piece of stone carving, but for what function was it originally Janet Bishop, made? The list is endless. Clearly the Swaledale Museum is spot on- Chair of the Friends of Swaledale Museum trend. -

Mould Side: Lead, Chert and Grit – a Circular Walk

Mould Side: Lead, Chert and Grit – a circular walk About 3.8 miles / 6.1 km or 3-4 hours when you stop and look at the landscape. Good walking boots and appropriate clothing is essential. There are several short sections usually no more than 20 metres in length, which are steep climbs or decents of grassy banks. You can usually zig-zag up these. Walking down Stoddart’s Hush requires walking of rocks but this isn’t very difficult other than choosing your path over the rocks. Stoddart’s Hush, by far the most spectacular hush to visit, is one of those ‘off the beaten track’ places which is well worth the effort of getting there. I have placed all the photographs at the end of this document, so that you can just print the front 5 text pages of the guide to take with you. Location: From Reeth turn by The Buck Hotel to go up Arkengarthdale. Between the village of Langthwaite and the CB Inn turn left towards Low Row (sign post = Low Row). The lane climbs up hill passing some large lead mining spoil heaps. Just passed the last spoil heap the lane continues to climb, but after approximately 200m it passes over a flat bridge with stone side-walls, located at the bottom of Turf Moor Hush. Park either side of this bridge on the grass verge. There is plenty of room for many cars. Route: Using your GPS follow the route up Turf Moor Hush. The first 20 minutes is all up hill. About 75-80% of the hill climbing is done whilst your are fresh. -

Name Bike Town Fred Adams Montesa Bristol Tom Affleck Cloburnmrs Sherco Saltburn Scott Aitkin EAM TRS Sedgfield Tom Alderson

Scott Trial Entry List 2017 Name Bike Town Fred Adams Montesa Bristol Tom Affleck CloburnMRS Sherco Saltburn Scott Aitkin EAM TRS Sedgfield Tom Alderson Cloburn Vertigo Cumbria Jordan Allanson Montesa Redcar Ben Allison-Hughes Beta Cleatlam Andrew Allum Beta Eppleby Matthew Alpe Inch Perfect Beta Clitheroe Andrew Anderson Scorpa Killin Phil Anstey Beta Wareham Philip Armstrong Beta Silsden Connor Atkinson RCM Sherco Ilfracombe Ian Austermuhle Beta-UK.COM Malton Matthew Baldwin Gas Gas Silsden Kev Barker Beta Gainford John Battensby MRS Sherco Cramlington Philip Baxter Sherco Blaydon Liston Bell Montesa Midlothian Lewis Bell Montesa Midlothian Tom Bennett TRS Staffs Edward Berry Montesa Skipton Russell Birley Gas Gas Scarborough Phil Blacka Sherco Keighley Bevan Blacker Gas Gas Boroughbridge Aldis Blacker Gas Gas Boroughbridge Billy Bolt BB57 Wallsend Joe Bradley Montesa Harrogate Lewis Braithwaite Beta Darlington Emma Bristow MRS Sherco Lincs William Brockbank Sherco Kendal Anthony Brown Beta Rossendale Nick Brown Sherco Leyburn Michael Brown JST GasGas Seamer Chris Brown TT AM Scorpa Middlesborough Brad Bullock Beta Tarporley Declan Bullock Gas Gas Tarporley Gareth Bunt Cloburn Gas Gas Skelton Lewis Byron Putoline Beta Glasgow Mark Cameron Sherco Devon Robert Carr Beta Skipton Miles Carruthers Sherco Hants Jack Challoner Craigs Montesa Halifax Sam Charlton Gas Gas Northallerton Kieran Child Beta Bradford Toby Churchill Sherco Devon Graham Clarkson Beta Scotton Thomas Coates Beta Arkengarthdale Sam Connor Beta Hampton Hill Billy Craig -

Swaledale Museum Newsletter 29 Spring 2020 Print

Newsletter No.29 Spring 2020 A message from the Curator As I write this, in mid-April, I am hoping that we will be able to resume ‘service as normal’ in the Museum this season. However any forward planning has become an almost impossible task as the situation changes from week to week. Ever the optimist I have decided to assume that we will be re-opening on 21st May and be running our programme of events. However, checking ahead will be paramount as we adapt to the latest guidelines. One of the benefits of the lockdown has been longer and more considered messages between Lidar image of Reeth - thanks to Stephen Eastmead acquaintances. I have, for example, been receiving regular pages from an ‘electronic diary of the plague marginalia in much loved and favourite books. months’ from an elderly friend living in a small hamlet. What sort of evidential trail are we leaving behind He wonderfully captures how small things have acquired us now, that will reflect what the Dale, the country greater meaning and value. I have been reading Jared and the world has gone through? How will curators Diamond’s The World Until Yesterday (2012) in which in the future present these episodes to the public? he compares how traditional and modern societies cope What projects are already in the making to tell the story of how we all reacted and coped? with life, looking at peace and danger, youth and age, language and health. He asks what can we learn from A severe blow to us all has been the loss of Janet ‘traditional’ societies? This spurred me to think about Bishop, Chairman of the Friends of the Museum. -

(""Tfrp Fiwa Dq,Bo

REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD 40 Free House_- Real Ales Bar snacks G^ZETTE _ _ ISSUE NO.212 JANUARY 2014 I - I I No iob roo smor rngr .rtiror., I Books & Maps RLduced rores for Senior I I I citizens I I Tel. 01748 884218 I I Tetephone 07875 253178 | STUBBS ELECTRICAL NORMAN F. BROWN CHARTERED Your Locol Electricol Service SURVEYOR5 & E5TATE A6ENT5 O Rewires/alterations SALES - LETTINGS - MANACEMITN'I' o Showers/storage heaters FREE'NO OBLIGATION' o Fire alarms/emergency lights MARKET APPRAISAL O Underfloor heating AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST O Fault finding 14 Queens Road, Richmond, Norlh Yorkslrirc, DLlO 4AG O Landlords' ceftificates T etz (017 4$ 82247 3 1822967 a PAT Testing www.norrnanfbrown.co.uk o Solar electric Contact Stephen on: T 0t748 822907 M:07980 l30Ol4 E: [email protected] ctrical.co.uk -i_o= ' '-:'' AND v '-: REPAI a, t o f M. - PLUMBING ! GUY J For all your o o plumbing requirements o a AGA'S & RAYBURN'S SERVICED RichardD 5,rnilh ! = Tel: 01748 - 825640 PA NTING & DECOFATING o s. A ghpp7 Al'eru. ta ynu ql.l, ^ To adveftise in the Gazette Quality Local o Vran Tradesmen please S''li;x::^',#* @ FREE NO OBUGIIBLIGATION o6 (rfim npur/J magazinp o contact the editor ! Wurt.k{,qL, FIXEDJD QUOTATIO OTATIONS 01748 88611U505. For { COMPLETEETE DIDECORATING,RATING SERVICE { t (""tfrp fiwa Dq,bo, adveftising rates please AtL APESS; BOTH IilTERNALIA IAL & EXTERUTEXTERI COVERED i o contact the treasurer t48 ! =.f 0L748 824824483 F 01748 884474. Mobile:07932 032501 . Emailr dspaintingl Slurdy,y Hous6 IFarm, ",ilx",""#31?i|lf***Whashton DLl 9 REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD REETH AND DISTRICT GAZETTE LTD 3 ( lAZlrl'l"l'li MANAGEMENT TEAM REETH & DISTRICT CAZETTE I,TD No material may be reproduced in whole or in part wilhout pcnnission. -

W Elcome to the Autumn 2010 Newsletter

Newsletter No.10 Autumn 2010 W elcome to the Autumn 2010 Newsletter A huge 'thank you' is due to everyone who has been involved with the Museum in any way over the past year, and I would particularly like to thank the Friends Committee. We try to help and support the work done in the Museum and personally, I have thoroughly enjoyed being a volunteer and meeting so many visitors. They are, very largely, extremely positive about their visit. A comment often heard is that they have a real sense of pleasure in being able to touch objects, which gives them a much closer feeling to their history. This is one of the many things that makes this museum so special. Susan Gibbings & Jo Evans from Leigh, North Island, Janet Bishop New Zealand with the lead mining display. Susan is a geologist & primary school teacher who came to see Swaledale after reading Adam Brunskill. C urator’s Report Although we have felt the effects of the ‘Credit Crunch’ with the best museums on local history [they] have visited’, & fewer visitors, we have had an action packed year & have Martin Amos from St Annes-on-Sea commented ‘Truly every reason to feel positive. Thanks to our new links with great things come in small packages’. We are delighted Marrick Priory & the University of Leeds Access Department that the Davies from Buxton felt the Museum is ‘a true we have had more children coming gem – [&] captures the spirit of the Dales’. than ever before. They revel in the Now the comment of one visitor, Mr Bucknell from opportunity to come close to the Wells, got me wondering. -

Swaledale & Arkengarthdale

Swaledale & Arkengarthdale The two far northern dales, with their The River Swale is one of England’s fastest industry, but in many places you will see iconic farming landscape of field barns and rising spate rivers, rushing its way between the dramatic remains of the former drystone walls, are the perfect place to Thwaite, Muker, Reeth and Richmond. leadmining industry. Find out more about retreat from a busy world and relax. local life at the Swaledale Museum in Reeth. On the moors you’re likely to see the At the head of Swaledale is the tiny village hardy Swaledale sheep, key to the Also in Reeth are great shops showcasing of Keld - you can explore its history at the livelihood of many Dales farmers - and the local photography and arts and crafts: Keld Countryside & Heritage Centre. This logo for the Yorkshire Dales National Park; stunning images at Scenic View Gallery and is the crossing point of the Coast to Coast in the valleys, tranquil hay meadows, at dramatic sculptures at Graculus, as well as Walk and the Pennine Way long distance their best in the early summer months. exciting new artists cooperative, Fleece. footpaths, and one end of the newest It is hard to believe these calm pastures Further up the valley in Muker is cosy cycle route, the Swale Trail (read more and wild moors were ever a site for Swaledale Woollens and the Old School about this on page 10). Gallery. The glorious wildflower meadows of Muker If you want to get active, why not learn navigation with one of the companies in the area that offer training courses or take to the hills on two wheels with Dales Bike Centre. -

Gunnerside, Swaledale – Conservation Area Character Appraisal

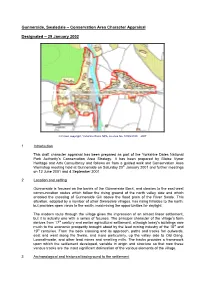

Gunnerside, Swaledale – Conservation Area Character Appraisal Designated – 29 January 2002 © Crown copyright, Yorkshire Dales NPA, Licence No. 100023740 2007 1 Introduction This draft character appraisal has been prepared as part of the Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority’s Conservation Area Strategy. It has been prepared by Blaise Vyner Heritage and Arts Consultancy and follows on from a guided walk and Conservation Area Workshop meeting held at Gunnerside on Saturday 20th January 2001 and further meetings on 12 June 2001 and 4 September 2001. 2 Location and setting Gunnerside is focused on the banks of the Gunnerside Beck, and cleaves to the east-west communication routes which follow the rising ground of the north valley side and which enabled the crossing of Gunnerside Gill above the flood plain of the River Swale. This situation, adopted by a number of other Swaledale villages, has rising hillsides to the north, but provides open views to the south, maximising the opportunities for daylight. The modern route through the village gives the impression of an almost linear settlement, but it is actually one with a series of focuses. The principal character of the village’s form derives from 17th century and earlier agricultural settlement, although today’s buildings owe much to the economic prosperity brought about by the lead mining industry of the 18th and 19th centuries. From the beck crossing and its approach, paths and tracks fan outwards, east and west along the Swale, and more particularly, up the valley side to Old Gang, Lownathwaite, and other lead mines and smelting mills. The tracks provides a framework upon which the settlement developed, variable in origin and structure so that now these various tracks are the most significant delineation of the various elements of the village. -

Swaledale Museum Newsletter 28 Autumn 2019 Draft

Newsletter No.28 Autumn 2019 T his really has been an incredible few months. The flooding brought all this amazing community together, as so often happens when some event like this happens. Thank you Helen for some memorable talks. I often wish you were here in the winter to liven up the next few months. I really enjoyed the auction, and although there were only seven of us there, plus a puppy, it turned out to be enormous fun. I think we all came away with items we had not planned on buying, which is what very often happens in auctions. Janet Bishop, Chair of the Friends of Swaledale Museum A message from the Curator As I write this the Museum is buzzing with activity, not with The aftermath of the July floods - © scenicview.co.uk visitors, but with building work. As ever with an old building grateful to them. I am delighted that Marie has offered there is always rescue work to be done. This time we are to become Minutes Secretary for the Friends of the concentrating on the ceiling and interior end walls, and one of Museum, and she has also been doing sterling work the sash windows. Thanks to the Friends we do not have to helping update our archive filing. Rob Macdonald is delay this work, and can get on with these repairs straight giving our website a boost, with a host of new ideas with away, which is a huge relief. a view to attracting more people not only to the site, but It has been a strange year.