What of Those Years of Rough Adventure, Weathered Under Zeus?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2010 Njcl Certamen Novice Division Round One

2010 NJCL CERTAMEN NOVICE DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. What effect did the flower of the lotus have upon the men of Odysseus? STOPPED CARING ABOUT HOME / DID NOT WANT TO GO BACK HOME / WANTED TO STAY IN LOTUS-EATER LAND / WEEP BITTERLY AS ODYSSEUS FORCED THEM BACK TO SHIPS B1: Who ate six of Odysseus' crewmen at another stop? POLYPHEMUS B2: What race of giant man-eaters crushed all but one of Odysseus' ships at another stop? LAESTRYGONIANS 2. From what Latin verb do we derive “adroit,” “dress,” “escort,” and “director”? REGŌ B1: Which one of these English words is also derived from regō: reciprocal, ruler, unrequited, rigidity? RULER B2: What English derivative of regō is a noun meaning “the denotation of a place where a person is located”? ADDRESS/REGION 3. Whose arrow was the first to strike the Calydonian boar? ATALANTA’S B1: What son of Oeneus, the king of Calydon, subsequently killed the boar? MELEAGER B2: What deity inflicted the monstrous boar upon Calydon after being offended by Oeneus? ARTEMIS 4. Give the vocative singular of the Latin noun meaning “son.” FĪLĪ B1: Give the vocative singular of the Latin noun meaning “poet.” POĒTA B2: Give the vocative of the phrase “my good friend.” MĪ AMĪCE BONE 5. What emperor lived a life of leisure while his father ruled the empire, and continued to do so in Campania after he was deposed by Odoacer? ROMULUS AUGUST(UL)US B1: What year was that overthrow of Romulus Augustulus? 476 AD B2: Who was Romulus Augustulus’ father, a name shared with a matricide in Greek tragedy? ORESTES 6. -

From the Odyssey, Part 1: the Adventures of Odysseus

from The Odyssey, Part 1: The Adventures of Odysseus Homer, translated by Robert Fitzgerald ANCHOR TEXT | EPIC POEM Archivart/Alamy Stock Photo Archivart/Alamy This version of the selection alternates original text The poet, Homer, begins his epic by asking a Muse1 to help him tell the story of with summarized passages. Odysseus. Odysseus, Homer says, is famous for fighting in the Trojan War and for Dotted lines appear next to surviving a difficult journey home from Troy.2 Odysseus saw many places and met many the summarized passages. people in his travels. He tried to return his shipmates safely to their families, but they 3 made the mistake of killing the cattle of Helios, for which they paid with their lives. NOTES Homer once again asks the Muse to help him tell the tale. The next section of the poem takes place 10 years after the Trojan War. Odysseus arrives in an island kingdom called Phaeacia, which is ruled by Alcinous. Alcinous asks Odysseus to tell him the story of his travels. I am Laertes’4 son, Odysseus. Men hold me formidable for guile5 in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky’s rim. My home is on the peaked sea-mark of Ithaca6 under Mount Neion’s wind-blown robe of leaves, in sight of other islands—Dulichium, Same, wooded Zacynthus—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy’s training; I shall not see on earth a place more dear, though I have been detained long by Calypso,7 loveliest among goddesses, who held me in her smooth caves to be her heart’s delight, as Circe of Aeaea,8 the enchantress, desired me, and detained me in her hall. -

The Odyssey Homer Translated Lv Robert Fitzç’Erald

I The Odyssey Homer Translated lv Robert Fitzç’erald PART 1 FAR FROM HOME “I Am Odysseus” Odysseus is in the banquet hail of Alcinous (l-sin’o-s, King of Phaeacia (fë-a’sha), who helps him on his way after all his comrades have been killed and his last vessel de stroyed. Odysseus tells the story of his adventures thus far. ‘I am Laertes’ son, Odysseus. [aertes Ia Men hold me formidable for guile in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky’s rim. My home is on the peaked sea-mark of Ithaca 4 Ithaca ith’. k) ,in island oft under Mount Neion’s wind-blown robe of leaves, the west e ast it C reece. in sight of other islands—Dulichium, Same, wooded Zacynthus—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy’s training; I (I 488 An Epic Poem I shall not see on earth a place more dear, though I have been detained long by Calypso,’ 12. Calypso k1ip’sö). loveliest among goddesses, who held me in her smooth caves, to be her heart’s delight, as Circe of Aeaea, the enchantress, 15 15. Circe (sür’së) of Aeaea e’e-). desired me, and detained me in her hail. But in my heart I never gave consent. Where shall a man find sweetness to surpass his OWfl home and his parents? In far lands he shall not, though he find a house of gold. -

Homer's Odyssey Bingo Myfreebingocards.Com

Homer's Odyssey Bingo myfreebingocards.com Safety First! Before you print all your bingo cards, please print a test page to check they come out the right size and color. Your bingo cards start on Page 3 of this PDF. If your bingo cards have words then please check the spelling carefully. If you need to make any changes go to mfbc.us/e/q95wuq Play Once you've checked they are printing correctly, print off your bingo cards and start playing! On the next page you will find the "Bingo Caller's Card" - this is used to call the bingo and keep track of which words have been called. Your bingo cards start on Page 3. Virtual Bingo Please do not try to split this PDF into individual bingo cards to send out to players. We have tools on our site to send out links to individual bingo cards. For help go to myfreebingocards.com/virtual-bingo. Help If you're having trouble printing your bingo cards or using the bingo card generator then please go to https://myfreebingocards.com/faq where you will find solutions to most common problems. Share Pin these bingo cards on Pinterest, share on Facebook, or post this link: mfbc.us/s/q95wuq Edit and Create To add more words or make changes to this set of bingo cards go to mfbc.us/e/q95wuq Go to myfreebingocards.com/bingo-card-generator to create a new set of bingo cards. Legal The terms of use for these printable bingo cards can be found at myfreebingocards.com/terms. -

A Dictionary of Mythology —

Ex-libris Ernest Rudge 22500629148 CASSELL’S POCKET REFERENCE LIBRARY A Dictionary of Mythology — Cassell’s Pocket Reference Library The first Six Volumes are : English Dictionary Poetical Quotations Proverbs and Maxims Dictionary of Mythology Gazetteer of the British Isles The Pocket Doctor Others are in active preparation In two Bindings—Cloth and Leather A DICTIONARY MYTHOLOGYOF BEING A CONCISE GUIDE TO THE MYTHS OF GREECE AND ROME, BABYLONIA, EGYPT, AMERICA, SCANDINAVIA, & GREAT BRITAIN BY LEWIS SPENCE, M.A. Author of “ The Mythologies of Ancient Mexico and Peru,” etc. i CASSELL AND COMPANY, LTD. London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne 1910 ca') zz-^y . a k. WELLCOME INS77Tint \ LIBRARY Coll. W^iMOmeo Coll. No. _Zv_^ _ii ALL RIGHTS RESERVED INTRODUCTION Our grandfathers regarded the study of mythology as a necessary adjunct to a polite education, without a knowledge of which neither the classical nor the more modem poets could be read with understanding. But it is now recognised that upon mythology and folklore rests the basis of the new science of Comparative Religion. The evolution of religion from mythology has now been made plain. It is a law of evolution that, though the parent types which precede certain forms are doomed to perish, they yet bequeath to their descendants certain of their characteristics ; and although mythology has perished (in the civilised world, at least), it has left an indelible stamp not only upon modem religions, but also upon local and national custom. The work of Fruger, Lang, Immerwahr, and others has revolutionised mythology, and has evolved from the unexplained mass of tales of forty years ago a definite and systematic science. -

Unit 5: Epic and Myth

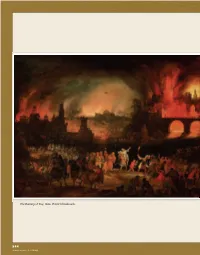

The Burning of Troy, 1606. Pieter Schoubroeck. 944 Archivo Iconografico, S.A./CORBIS UNIT FIVE Epic and Myth Looking Ahead Many centuries ago, before books, magazines, paper, and pencils were invented, people recited their stories. Some of the stories they told offered explanations of natural phenomena, such as thunder and lightning, or the culture’s customs or beliefs. Other stories were meant for entertainment. Taken together, these stories—these myths, epics, and legends—tell a history of loyalty and betrayal, heroism and cowardice, love and rejection. In this unit, you will explore the literary elements that make them unique. PREVIEW Big Ideas and Literary Focus BIG IDEA: LITERARY FOCUS: 1 Journeys Hero BIG IDEA: LITERARY FOCUS: 2 Courage and Cleverness Archetype OBJECTIVES In learning about the genres of epic and myth, • identifying and exploring literary elements you will focus on the following: significant to the genres • understanding characteristics of epics and myths • analyzing the effect that these literary elements have upon the reader 945 Genre Focus: Epic and Myth What is unique about epics and myths? Why do we read stories from the distant past? answer. He thought that in order for us to under- Why should we care about heroes and villains long stand the people we are today, we have to learn dead? About cities and palaces that were destroyed about those who came before us. One way to do centuries before our time? The noted psychologist that, Jung believed, was to read the myths and and psychiatrist Carl Jung thought he knew the epics of long ago. -

The Cyclopes and Asclepius

The Cyclopes and Asclepius According to Hesiod (Theogony, 139-146) Gaia (“Earth”) laid with with Uranus (“Sky”) and produced the “overbearing in spirit” Cyclopes. Their names were Brontes ("thunderer"), Steropes ("lightning") and Arges ("bright"). They had a single eye in the middle of their forehead, they were strong and stubborn but they were very skilled blacksmiths and made thunder and thunderbolt for Zeus. According to Hesiod (Theogony, 492-505), once Zeus had grown up, Gaia (“Earth”) forced Cronos to vomit Zeus’ siblings which Cronos previously swallowed. This happened in reverse order starting from the stone, which was set down at Pytho under the glens of Mount Parnassus to be a sign to mortal men, then his two brothers and three sisters. Then Zeus freed the brothers of his father (these would be the Cyclopes) which Cronos imprisoned in Tartarus. These, in exchange for his kindness, gave Zeus thunder, glowing thunderbolt and lightning. According to Pseudo-Apollodorus (Biblioteca, 1.1.2) Earth coupled with Sky and gave him the Cyclopes: Arges, Steropes and Brontes. Each had one eye in the forehead. However, Sky bound them in Tartarus, a “gloomy place in Hades as far distant from earth as earth is distant from the sky”. According to Pseudo-Apollodorus (Bibliotheca, 1.2.1) when Zeus had grown up he sought the help of Metis, daughter of Oceanus (“Ocean”), who gave Cronus an emetic to force him to disgorge the children he had previously swallowed. Zeus then waged a ten-year war against Cronus and the Titans. He first freed the Hecatoncheires after slewing Campe (the female dragon that was given the task by Cronus to guard them). -

2014 Tsjcl Myth

CONTEST CODE: 09 2014 TEXAS STATE JUNIOR CLASSICAL LEAGUE MYTHOLOGY TEST DIRECTIONS: Please mark the letter of the correct answer on your scantron answer sheet. 1. Goddess of the hunt, she is associated with Selene, goddess of the moon (A) Aphrodite (B) Artemis (C) Athena (D) Aurora 2. He performed Twelve Labors for his cousin due to a trick by Hera (A) Admetus (B) Heracles (C) Jason (D) Perseus 3. They were the Dioscuri, the Gemini Twins (A) Apollo & Artemis (B) Idas & Lynceus (C) Otus & Ephialtes (D) Pollux & Castor 4. He led the Trojan refugees to a new land and their destiny (A) Aeneas (B) Jason (C) Odysseus (D) Teucer 5. Goddess of love and beauty (A) Aphrodite (B) Demeter (C) Hera (D) Themis 6. King of the Underworld, brother to Zeus (A) Apollo (B) Hades (C) Poseidon (D) Vulcan 7. A Satyr, half goat and half man, patron of shepherds (A) Chiron (B) Echidna (C) Ladon (D) Pan 8. God of the Sea, known as The Earth-Shaker (A) Ares (B) Hephaestus (C) Jupiter (D) Poseidon 9. She and her husband Philemon welcomed the disguised Zeus and Hermes to their home (A) Baucis (B) Laodice (C) Oenone (D) Semiramis 10. This beast was defeated by Heracles when he lopped off its heads and seared the stumps (A) Cerberus (B) Chimaera (C) Echidna (D) Hydra 11. Zeus gave Aphrodite to this god as his wife, an interesting choice (A) Apollo (B) Ares (C) Hephaestus (D) Poseidon 12. Zeus changed her into a heifer in order to hide her from Hera (A) Danae (B) Io (C) Merope (D) Semele 13. -

Odyssey Homer Translated by Robert Fitzgerald

ANCHOR TEXT | EPIC POEM from the Odyssey Homer translated by Robert Fitzgerald Part I The Adventures of Odysseus © Pearson Education, Inc., or its affiliates. All rights reserved. or its affiliates. Inc., Education, © Pearson CHARACTERS Alcinous (al SIHN oh uhs)—king of the Phaeacians, Tiresias (ty REE see uhs)—blind prophet who to whom Odysseus tells his story advises Odysseus Odysseus (oh Dihs ee uhs)—king of Ithaca Persephone (puhr SEHF uh nee)—wife of Hades Calypso (kuh LIHP soh)—sea goddess who loves Telemachus (tuh LEHM uh kuhs)—Odysseus and Odysseus Penelope’s son Circe (SUR see)—enchantress who helps Odysseus Sirens (SY ruhnz)—creatures whose songs lure sailors to their deaths Zeus (zoos)—king of the gods Scylla (SIHL uh)—sea monster of gray rock Apollo (uh POL oh)—god of music, poetry, prophecy, and medicine Charybdis (kuh RIHB dihs)—enormous and dangerous whirlpool Agamemnon (ag uh MEHM non)—king and leader of Greek forces Lampetia (lahm PEE shuh)—nymph Poseidon (poh SY duhn)—god of sea, earthquakes, Hermes (HUR meez)—herald and messenger of the horses, and storms at sea gods Athena (uh THEE nuh)—goddess of wisdom, skills, Eumaeus (yoo MEE uhs)—old swineherd and friend and warfare of Odysseus Polyphemus (pol ih FEE muhs)—the Cyclops who Antinous (ant IHN oh uhs)—leader among the imprisons Odysseus suitors Laertes (lay ur teez)—Odysseus’ father Eurynome (yoo RIHN uh mee)—housekeeper for Penelope Cronus (KROH nuhs)—Titan ruler of the universe; father of Zeus Penelope (puh NEHL uh pee)—Odysseus’ wife Perimedes (pehr uh MEE deez)—member of Eurymachus (yoo RIH muh kuhs)—suitor Odysseus’ crew Amphinomus (am FIHN uh muhs)—suitor Eurylochus (yoo RIHL uh kuhs)—another member of the crew SCAN FOR MULTIMEDIA In the opening verses, Homer addresses the muse of epic NOTES poetry. -

Ovid's Metamorphosis of the Famous Apologoi

Ovid’s metamorphosis of the famous Apologoi A narratological study into Odysseus’ wanderings as told by Homer and Ovid MA Thesis University of Amsterdam/Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Faculty of Humanities MA Classics Radhika S. Sahtie Contact: [email protected] [email protected] Student number: 10714553 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. I.J.F. de Jong Second assessor: Dr. M.A.J. Heerink Word count: 20567 Date of completion: June 15th 2020 1 I hereby declare that this dissertation is an original piece of work, written by myself alone. Any information and ideas from other sources are acknowledged fully in the text and notes. Amsterdam, 15th of june 2020 (place, date) (signature) 2 Table of contents Introduction ....................................................................................................4 Chapter 1. The Cyclops episode ...........................................................................7 Part one: A first analysis .....................................................................................8 1.1 Structure ........................................................................................................................ 8 1.2 Narrator and narratee ..................................................................................................... 8 1.3 Focalization ................................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Time ........................................................................................................................... -

Book 9: New Coasts and Poseidon’S Son

book 9: New Coasts and Poseidon’s Son In Books 6–8, Odysseus is welcomed by King Alcinous, who gives a banquet in his honor. That night the king begs Odysseus to tell who he is and what has happened to him. In Books 9–12, Odysseus relates to the king his adventures. “i am laertes’ son” ANALYZE VISUALS “What shall I This sculpture of Odysseus was produced in Rome sometime say first? What shall I keep until the end? between a.d. 4 and 26. How would The gods have tried me in a thousand ways. you describe the expression on But first my name: let that be known to you, his face? 5 and if I pull away from pitiless death, friendship will bind us, though my land lies far. I am Laertes’ son, Odysseus. Men hold me 7–8 hold me formidable for guile: formidable for guile in peace and war: consider me impressive for my cunning and craftiness. this fame has gone abroad to the sky’s rim. 10 My home is on the peaked sea-mark of Ithaca under Mount Neion’s wind-blown robe of leaves, 11–13 Mount Neion’s (nCPJnzQ); Dulichium in sight of other islands—Dulichium, (dL-lGkPC-Em); Same (sAPmC); Zacynthus (zE-sGnPthEs). Same, wooded Zacynthus—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, 15 and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy’s training; I shall not see on earth a place more dear, 18–26 Odysseus refers to two beautiful though I have been detained long by Calypso, goddesses, Calypso and Circe, who have delayed him on their islands. -

Myth World Quest Before They Begin This Unit

¬ELA The Greeks FLORIDA Teacher Edition • Grade 6 The Greeks Published and Distributed by Amplify. © 2021 Amplify Education, Inc. 55 Washington Street, Suite 800, Brooklyn, NY 11201 www.amplify.com All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form, or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written consent of Amplify Education, Inc., except for the classroom use of the worksheets included for students in some lessons. ISBN: 978-1-64383-551-8 Printed in the United States of America 01 LSC 2020 Contents 6D: The Greeks Unit Overview 2 Prometheus SUB-UNIT 1 Sub-Unit 1 Overview 4 Sub-Unit 1 At a Glance & Preparation Checklist 6 Sub-Unit 1: 6 Lessons 18 Odysseus SUB-UNIT 2 Sub-Unit 2 Overview 28 Sub-Unit 2 At a Glance & Preparation Checklist 30 Sub-Unit 2: 7 Lessons 55 Arachne SUB-UNIT 3 Sub-Unit 3 Overview 62 Sub-Unit 3 At a Glance & Preparation Checklist 64 Sub-Unit 3: 6 Lessons 82 Write an Essay SUB-UNIT 4 Sub-Unit 4 Overview 92 Sub-Unit 4 At a Glance & Preparation Checklist 94 Sub-Unit 4: 5 Lessons 96 Clarify & Compare SUB-UNIT 5 Lesson and print materials in digital curriculum. Unit Reading Assessment ASSESSMENT Assessment and print materials in digital curriculum. Icon Key: Steps: Indicates the Exit Ticket Poll Teacher Only order of activities in a lesson Highlight/Annotate Projection Teacher Speech Audio Image Share Video Close Reading Materials Spotlight Warm-Up Differentiation On-the-Fly Student Edition Wrap-Up Digital App Pair Activity Student Groups Writing Journal PDF Teacher-Led Discussion The Greeks The stories of world mythologies have a timeless quality.