The Odyssey by Homer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sophocles, Ajax, Lines 1-171

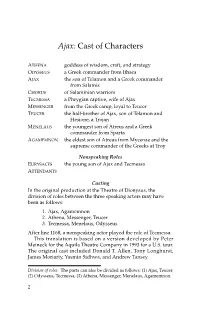

SophoclesFourTrag-00Bk Page 2 Thursday, July 26, 2007 3:56 PM Ajax: Cast of Characters ATHENA goddess of wisdom, craft, and strategy ODYSSEUS a Greek commander from Ithaca AJAX the son of Telamon and a Greek commander from Salamis CHORUS of Salaminian warriors TECMESSA a Phrygian captive, wife of Ajax MESSENGER from the Greek camp, loyal to Teucer TEUCER the half-brother of Ajax, son of Telamon and Hesione, a Trojan MENELAUS the youngest son of Atreus and a Greek commander from Sparta AGAMEMNON the eldest son of Atreus from Mycenae and the supreme commander of the Greeks at Troy Nonspeaking Roles EURYSACES the young son of Ajax and Tecmessa ATTENDANTS Casting In the original production at the Theatre of Dionysus, the division of roles between the three speaking actors may have been as follows: 1. Ajax, Agamemnon 2. Athena, Messenger, Teucer 3. Tecmessa, Menelaus, Odysseus After line 1168, a nonspeaking actor played the role of Tecmessa. This translation is based on a version developed by Peter Meineck for the Aquila Theatre Company in 1993 for a U.S. tour. The original cast included Donald T. Allen, Tony Longhurst, James Moriarty, Yasmin Sidhwa, and Andrew Tansey. Division of roles: The parts can also be divided as follows: (1) Ajax, Teucer; (2) Odysseus, Tecmessa; (3) Athena, Messenger, Menelaus, Agamemnon. 2 SophoclesFourTrag-00Bk Page 3 Thursday, July 26, 2007 3:56 PM Ajax SCENE: Night. The Greek camp at Troy. It is the ninth year of the Trojan War, after the death of Achilles. Odysseus is following tracks that lead him outside the tent of Ajax. -

2010 Njcl Certamen Novice Division Round One

2010 NJCL CERTAMEN NOVICE DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. What effect did the flower of the lotus have upon the men of Odysseus? STOPPED CARING ABOUT HOME / DID NOT WANT TO GO BACK HOME / WANTED TO STAY IN LOTUS-EATER LAND / WEEP BITTERLY AS ODYSSEUS FORCED THEM BACK TO SHIPS B1: Who ate six of Odysseus' crewmen at another stop? POLYPHEMUS B2: What race of giant man-eaters crushed all but one of Odysseus' ships at another stop? LAESTRYGONIANS 2. From what Latin verb do we derive “adroit,” “dress,” “escort,” and “director”? REGŌ B1: Which one of these English words is also derived from regō: reciprocal, ruler, unrequited, rigidity? RULER B2: What English derivative of regō is a noun meaning “the denotation of a place where a person is located”? ADDRESS/REGION 3. Whose arrow was the first to strike the Calydonian boar? ATALANTA’S B1: What son of Oeneus, the king of Calydon, subsequently killed the boar? MELEAGER B2: What deity inflicted the monstrous boar upon Calydon after being offended by Oeneus? ARTEMIS 4. Give the vocative singular of the Latin noun meaning “son.” FĪLĪ B1: Give the vocative singular of the Latin noun meaning “poet.” POĒTA B2: Give the vocative of the phrase “my good friend.” MĪ AMĪCE BONE 5. What emperor lived a life of leisure while his father ruled the empire, and continued to do so in Campania after he was deposed by Odoacer? ROMULUS AUGUST(UL)US B1: What year was that overthrow of Romulus Augustulus? 476 AD B2: Who was Romulus Augustulus’ father, a name shared with a matricide in Greek tragedy? ORESTES 6. -

Sea Monsters in Antiquity: a Classical and Zoological Investigation

Sea Monsters in Antiquity: A Classical and Zoological Investigation Alexander L. Jaffe Harvard University Dept. of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology Class of 2015 Abstract: Sea monsters inspired both fascination and fear in the minds of the ancients. In this paper, I aim to examine several traditional monsters of antiquity with a multi-faceted approach that couples classical background with modern day zoological knowledge. Looking at the examples of the ketos and the sea serpent in Roman and Greek societies, I evaluate the scientific bases for representations of these monsters across of variety of media, from poetry to ceramics. Through the juxtaposition of the classical material and modern science, I seek to gain a greater understanding of the ancient conception of sea monsters and explain the way in which they were rationalized and depicted by ancient cultures. A closer look at extant literature, historical accounts, and artwork also helps to reveal a human sentiment towards the ocean and its denizens penetrating through time even into the modern day. “The Sea-monsters, mighty of limb and huge, the wonders of the sea, heavy with strength invincible, a terror for the eyes to behold and ever armed with deadly rage—many of these there be that roam the spacious seas...”1 Oppian, Halieutica 1 As the Greek poet Oppian so eloquently reveals, sea monsters inspired both fascination and fear in the minds of the ancients. From the Old Testament to Ovid, sources from throughout the ancient world show authors exercising both imagination and observation in the description of these creatures. Mythology as well played a large role in the creation of these beliefs, with such classic examples as Perseus and Andromeda or Herakles and Hesione. -

A Language-Exercise in Dramatization

A LANGUAGE-EXERCISE IN DRAMATIZATION EMMA SIEBEL No material presented for a language-exercise and no form of language-work has awakened in the children a more intense interest or provoked them to greater effort than have the stories of the gods and the Trojan war, and especially the writing of the play which follows. The exercise is classwork, and all the children are represented, some contributing more than others; all, however, working with earnestness and each doing his part. There was quite a heated discussion as to the subject to be chosen-some favoring the "Wedding Feast," others contending that that would be too simple, that it would only necessitate allow- ing the characters to say "in their own words" what the story had told them. They wished to "make up" their play, and the suggestion that we write on "Laomedon's Broken Promises," that being a story from which "a good lesson could be learned," carried the day. I had some misgivings as to the outcome, but would not discourage their enthusiastic effort. The story of Cinderella, so familiar to all, was acted out to give them the "play-idea" and to familiarize them with the terms "exit," "enter," "act," "scene," "speech," "action," etc. We then spent one lesson "practicing," as they said, "the language of the gods," and another in changing sentences, "to make them sound more poetical." The suggestion to substitute "Persons of the Play" for "Cast of Characters" came from a little girl who thought that "we are only children, and we want it to be all our own." They then selected the characters needed, deciding that we could easily add others should we have need of them. -

From the Odyssey, Part 1: the Adventures of Odysseus

from The Odyssey, Part 1: The Adventures of Odysseus Homer, translated by Robert Fitzgerald ANCHOR TEXT | EPIC POEM Archivart/Alamy Stock Photo Archivart/Alamy This version of the selection alternates original text The poet, Homer, begins his epic by asking a Muse1 to help him tell the story of with summarized passages. Odysseus. Odysseus, Homer says, is famous for fighting in the Trojan War and for Dotted lines appear next to surviving a difficult journey home from Troy.2 Odysseus saw many places and met many the summarized passages. people in his travels. He tried to return his shipmates safely to their families, but they 3 made the mistake of killing the cattle of Helios, for which they paid with their lives. NOTES Homer once again asks the Muse to help him tell the tale. The next section of the poem takes place 10 years after the Trojan War. Odysseus arrives in an island kingdom called Phaeacia, which is ruled by Alcinous. Alcinous asks Odysseus to tell him the story of his travels. I am Laertes’4 son, Odysseus. Men hold me formidable for guile5 in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky’s rim. My home is on the peaked sea-mark of Ithaca6 under Mount Neion’s wind-blown robe of leaves, in sight of other islands—Dulichium, Same, wooded Zacynthus—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy’s training; I shall not see on earth a place more dear, though I have been detained long by Calypso,7 loveliest among goddesses, who held me in her smooth caves to be her heart’s delight, as Circe of Aeaea,8 the enchantress, desired me, and detained me in her hall. -

Folktale Types and Motifs in Greek Heroic Myth Review P.11 Morphology of the Folktale, Vladimir Propp 1928 Heroic Quest

Mon Feb 13: Heracles/Hercules and the Greek world Ch. 15, pp. 361-397 Folktale types and motifs in Greek heroic myth review p.11 Morphology of the Folktale, Vladimir Propp 1928 Heroic quest NAME: Hera-kleos = (Gk) glory of Hera (his persecutor) >p.395 Roman name: Hercules divine heritage and birth: Alcmena +Zeus -> Heracles pp.362-5 + Amphitryo -> Iphicles Zeus impersonates Amphityron: "disguised as her husband he enjoyed the bed of Alcmena" “Alcmena, having submitted to a god and the best of mankind, in Thebes of the seven gates gave birth to a pair of twin brothers – brothers, but by no means alike in thought or in vigor of spirit. The one was by far the weaker, the other a much better man, terrible, mighty in battle, Heracles, the hero unconquered. Him she bore in submission to Cronus’ cloud-ruling son, the other, by name Iphicles, to Amphitryon, powerful lancer. Of different sires she conceived them, the one of a human father, the other of Zeus, son of Cronus, the ruler of all the gods” pseudo-Hesiod, Shield of Heracles Hera tries to block birth of twin sons (one per father) Eurystheus born on same day (Hera heard Zeus swear that a great ruler would be born that day, so she speeded up Eurystheus' birth) (Zeus threw her out of heaven when he realized what she had done) marvellous infancy: vs. Hera’s serpents Hera, Heracles and the origin of the MIlky Way Alienation: Madness of Heracles & Atonement pp.367,370 • murders wife Megara and children (agency of Hera) Euripides, Heracles verdict of Delphic oracle: must serve his cousin Eurystheus, king of Mycenae -> must perform 12 Labors (‘contests’) for Eurystheus -> immortality as reward The Twelve Labors pp.370ff. -

The Odyssey Homer Translated Lv Robert Fitzç’Erald

I The Odyssey Homer Translated lv Robert Fitzç’erald PART 1 FAR FROM HOME “I Am Odysseus” Odysseus is in the banquet hail of Alcinous (l-sin’o-s, King of Phaeacia (fë-a’sha), who helps him on his way after all his comrades have been killed and his last vessel de stroyed. Odysseus tells the story of his adventures thus far. ‘I am Laertes’ son, Odysseus. [aertes Ia Men hold me formidable for guile in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky’s rim. My home is on the peaked sea-mark of Ithaca 4 Ithaca ith’. k) ,in island oft under Mount Neion’s wind-blown robe of leaves, the west e ast it C reece. in sight of other islands—Dulichium, Same, wooded Zacynthus—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy’s training; I (I 488 An Epic Poem I shall not see on earth a place more dear, though I have been detained long by Calypso,’ 12. Calypso k1ip’sö). loveliest among goddesses, who held me in her smooth caves, to be her heart’s delight, as Circe of Aeaea, the enchantress, 15 15. Circe (sür’së) of Aeaea e’e-). desired me, and detained me in her hail. But in my heart I never gave consent. Where shall a man find sweetness to surpass his OWfl home and his parents? In far lands he shall not, though he find a house of gold. -

Child Abuse in Greek Mythology: a Review C Stavrianos, I Stavrianou, P Kafas

The Internet Journal of Forensic Science ISPUB.COM Volume 3 Number 1 Child Abuse in Greek Mythology: A Review C Stavrianos, I Stavrianou, P Kafas Citation C Stavrianos, I Stavrianou, P Kafas. Child Abuse in Greek Mythology: A Review. The Internet Journal of Forensic Science. 2007 Volume 3 Number 1. Abstract The aim of this review was to describe child abuse cases in ancient Greek mythology. Names like Hercules, Saturn, Aesculapius, Medea are very familiar. The stories can be divided into 3 categories: child abuse from gods to gods, from gods to humans and from humans to humans. In these stories children were abused in different ways and the reasons were of social, financial, political, religious, medical and sexual origin. The interpretations of the myths differed and the conclusions seemed controversial. Archaeologists, historians, and philosophers still try to bring these ancient stories into light in connection with the archaeological findings. The possibility for a dentist to face a child abuse case in the dental office nowadays proved the fact that child abuse was not only a phenomenon of the past but also a reality of the present. INTRODUCTION courses are easily available to everyone. Child abuse may be defined as any non-accidental trauma, On 1860 the forensic odontologist Ambroise Tardieu, neglect, failure to meet basic needs or abuse inflicted upon a referring to 32 cases, made a connection between subdural child by a caretaker that is beyond the acceptable norm of haematoma and abuse. In 1874 a church group in New York childcare in our culture. Abused children found in all 1 City took a child named Mary-Helen from home in which economic, social, ethnic and cultural backgrounds and she was being abused. -

Heracles on Top of Troy in the Casa Di Octavius Quartio in Pompeii Katharina Lorenz

9 | Split-screen visions: Heracles on top of Troy in the Casa di Octavius Quartio in Pompeii katharina lorenz The houses of Pompeii are full of mythological images, several of which present scenes of Greek, few of Roman epic.1 Epic visions, visual experi- ences derived from paintings featuring epic story material, are, therefore, a staple feature in the domestic sphere of the Campanian town throughout the late first century BCE and the first century CE until the destruction of the town in 79 CE. The scenes of epic, and mythological scenes more broadly, profoundly undercut the notion that such visualisations are merely illustration of a textual manifestation; on the contrary: employing a diverse range of narrative strategies and accentuations, they elicit content exclusive to the visual domain, and rub up against the conventional, textual classifications of literary genres. The media- and genre-transgressing nature of Pompeian mythological pictures renders them an ideal corpus of material to explore what the relationships are between visual representations of epic and epic visions, what characterises the epithet ‘epic’ when transferred to the visual domain, and whether epic visions can only be generated by stories which the viewer associates with a text or texts of the epic genre. One Pompeian house in particular provides a promising framework to study this: the Casa di Octavius Quartio, which in one of its rooms combines two figure friezes in what is comparable to the modern cinematographic mode of the split screen. Modern study has been reluctant to discuss these pictures together,2 1 Vitruvius (7.5.2) differentiates between divine, mythological and Homeric decorations, emphasising the special standing of Iliad and Odyssey in comparison to the overall corpus of mythological depictions; cf. -

Homer's Odyssey Bingo Myfreebingocards.Com

Homer's Odyssey Bingo myfreebingocards.com Safety First! Before you print all your bingo cards, please print a test page to check they come out the right size and color. Your bingo cards start on Page 3 of this PDF. If your bingo cards have words then please check the spelling carefully. If you need to make any changes go to mfbc.us/e/q95wuq Play Once you've checked they are printing correctly, print off your bingo cards and start playing! On the next page you will find the "Bingo Caller's Card" - this is used to call the bingo and keep track of which words have been called. Your bingo cards start on Page 3. Virtual Bingo Please do not try to split this PDF into individual bingo cards to send out to players. We have tools on our site to send out links to individual bingo cards. For help go to myfreebingocards.com/virtual-bingo. Help If you're having trouble printing your bingo cards or using the bingo card generator then please go to https://myfreebingocards.com/faq where you will find solutions to most common problems. Share Pin these bingo cards on Pinterest, share on Facebook, or post this link: mfbc.us/s/q95wuq Edit and Create To add more words or make changes to this set of bingo cards go to mfbc.us/e/q95wuq Go to myfreebingocards.com/bingo-card-generator to create a new set of bingo cards. Legal The terms of use for these printable bingo cards can be found at myfreebingocards.com/terms. -

The Trojan War

THE TROJAN WAR PART ONE: THE ORIGINS OF THE TROJAN WAR have actually revealed weaker stonework on the western walls of Troy, suggesting that a genuine difference in construction led to the myth that The city of Troy had several mythical founders and kings, the two gods built the other walls. including Teucer, Dardanus, Tros, Ilus and Assaracus. The most widely accepted story makes Ilus the actual founder, Mythical reasons behind the Trojan War and from him the city took the name it was best-known by in ancient times, Ilium. In an episode similar to the founding During Priam's of Thebes, Ilus was given a cow and told to found a city lifetime Troy where it first lay down. As instructed, he followed the reached its animal, and on the land where it rested drew up the greatest boundaries of his city. He then received an additional sign prosperity, but from the gods, a legless wooden statue called the Palladium, when he was a which dropped from the heavens with the message that it very old man it should be carefully guarded as it 'brought empire'. Some say was tota lly it was a statue of Athene's friend Pallas, but most believe it destroyed after a was of Athene herself and that this statue was to make Troy ten-year siege by a great city. warriors from Greece. Some say Laomedon's Troy Zeus himself Ilus was succeeded by his son Laomedon, who built great caused the Trojan walls around his city with the help of a mortal, Aeacus, and War to thin out the two gods Poseidon and Apollo. -

A Dictionary of Mythology —

Ex-libris Ernest Rudge 22500629148 CASSELL’S POCKET REFERENCE LIBRARY A Dictionary of Mythology — Cassell’s Pocket Reference Library The first Six Volumes are : English Dictionary Poetical Quotations Proverbs and Maxims Dictionary of Mythology Gazetteer of the British Isles The Pocket Doctor Others are in active preparation In two Bindings—Cloth and Leather A DICTIONARY MYTHOLOGYOF BEING A CONCISE GUIDE TO THE MYTHS OF GREECE AND ROME, BABYLONIA, EGYPT, AMERICA, SCANDINAVIA, & GREAT BRITAIN BY LEWIS SPENCE, M.A. Author of “ The Mythologies of Ancient Mexico and Peru,” etc. i CASSELL AND COMPANY, LTD. London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne 1910 ca') zz-^y . a k. WELLCOME INS77Tint \ LIBRARY Coll. W^iMOmeo Coll. No. _Zv_^ _ii ALL RIGHTS RESERVED INTRODUCTION Our grandfathers regarded the study of mythology as a necessary adjunct to a polite education, without a knowledge of which neither the classical nor the more modem poets could be read with understanding. But it is now recognised that upon mythology and folklore rests the basis of the new science of Comparative Religion. The evolution of religion from mythology has now been made plain. It is a law of evolution that, though the parent types which precede certain forms are doomed to perish, they yet bequeath to their descendants certain of their characteristics ; and although mythology has perished (in the civilised world, at least), it has left an indelible stamp not only upon modem religions, but also upon local and national custom. The work of Fruger, Lang, Immerwahr, and others has revolutionised mythology, and has evolved from the unexplained mass of tales of forty years ago a definite and systematic science.