Heracles on Top of Troy in the Casa Di Octavius Quartio in Pompeii Katharina Lorenz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sophocles, Ajax, Lines 1-171

SophoclesFourTrag-00Bk Page 2 Thursday, July 26, 2007 3:56 PM Ajax: Cast of Characters ATHENA goddess of wisdom, craft, and strategy ODYSSEUS a Greek commander from Ithaca AJAX the son of Telamon and a Greek commander from Salamis CHORUS of Salaminian warriors TECMESSA a Phrygian captive, wife of Ajax MESSENGER from the Greek camp, loyal to Teucer TEUCER the half-brother of Ajax, son of Telamon and Hesione, a Trojan MENELAUS the youngest son of Atreus and a Greek commander from Sparta AGAMEMNON the eldest son of Atreus from Mycenae and the supreme commander of the Greeks at Troy Nonspeaking Roles EURYSACES the young son of Ajax and Tecmessa ATTENDANTS Casting In the original production at the Theatre of Dionysus, the division of roles between the three speaking actors may have been as follows: 1. Ajax, Agamemnon 2. Athena, Messenger, Teucer 3. Tecmessa, Menelaus, Odysseus After line 1168, a nonspeaking actor played the role of Tecmessa. This translation is based on a version developed by Peter Meineck for the Aquila Theatre Company in 1993 for a U.S. tour. The original cast included Donald T. Allen, Tony Longhurst, James Moriarty, Yasmin Sidhwa, and Andrew Tansey. Division of roles: The parts can also be divided as follows: (1) Ajax, Teucer; (2) Odysseus, Tecmessa; (3) Athena, Messenger, Menelaus, Agamemnon. 2 SophoclesFourTrag-00Bk Page 3 Thursday, July 26, 2007 3:56 PM Ajax SCENE: Night. The Greek camp at Troy. It is the ninth year of the Trojan War, after the death of Achilles. Odysseus is following tracks that lead him outside the tent of Ajax. -

Acquisitions

Acquisitions Objects are presented in order of acquisition. African Art Ancient and 2008–09. Gift of A Practice for Everyday Life (APFEL), and Indian Art Byzantine Art 2013.1058. of the Americas A Practice for Everyday Life Finger Ring with Intaglio (APFEL) (English, founded Depicting Eros, 3rd century 2003), Kirsty Carter (English, Container Depicting Warriors, a.d., Roman. Gift of Dorothy born 1979), Emma Thomas Rulers, and Winged Beings with Braude Edinburg to the (English, born 1979), Performa Trophy Heads, 180 b.c./a.d. Harry B. and Bessie K. 09 Graphic Identity System, 500, Nazca, South Coast, Braude Memorial Collection, 2009. Gift of A Practice Peru. Gift of Edward and Betty 2013.1105. for Everyday Life (APFEL), Harris, 2004.1154. Solidus of Empress Irene, a.d. 2013.1059. 797/802, Byzantine, minted A Practice for Everyday Life in Constantinople. Gift of the (APFEL) (English, founded American Art Classical Art Society, 2014.9. 2003), Kirsty Carter (English, Statuette of a Woman, c. 450 b.c., born 1979), Emma Thomas J. Robert F. Swanson (1900– Greek, Boeotia. Katherine K. (English, born 1979), Performa 1981), Pipsan Saarinen Adler Memorial Fund, 11 Graphic Identity System, Swanson (1905–1979), Eliel 2014.969. 2011. Gift of A Practice Saarinen (1873–1950), made for Everyday Life (APFEL), by Johnson Furniture Company 2013.1060. (1908–1983), Nesting Tables, Architecture A Practice for Everyday Life c. 1939. Gift of Suzanne (APFEL) (English, founded Langsdorf in memory of Martyl and Design 2003), Kirsty Carter (English, and Alexander Langsdorf, born 1979), Emma Thomas 2006.194.1–3. Joel Sanders (American, born (English, born 1979), Performa Union Porcelain Works (1863– 1956), Karen Van Lengen Relâche Party Invite Card and c. -

Sea Monsters in Antiquity: a Classical and Zoological Investigation

Sea Monsters in Antiquity: A Classical and Zoological Investigation Alexander L. Jaffe Harvard University Dept. of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology Class of 2015 Abstract: Sea monsters inspired both fascination and fear in the minds of the ancients. In this paper, I aim to examine several traditional monsters of antiquity with a multi-faceted approach that couples classical background with modern day zoological knowledge. Looking at the examples of the ketos and the sea serpent in Roman and Greek societies, I evaluate the scientific bases for representations of these monsters across of variety of media, from poetry to ceramics. Through the juxtaposition of the classical material and modern science, I seek to gain a greater understanding of the ancient conception of sea monsters and explain the way in which they were rationalized and depicted by ancient cultures. A closer look at extant literature, historical accounts, and artwork also helps to reveal a human sentiment towards the ocean and its denizens penetrating through time even into the modern day. “The Sea-monsters, mighty of limb and huge, the wonders of the sea, heavy with strength invincible, a terror for the eyes to behold and ever armed with deadly rage—many of these there be that roam the spacious seas...”1 Oppian, Halieutica 1 As the Greek poet Oppian so eloquently reveals, sea monsters inspired both fascination and fear in the minds of the ancients. From the Old Testament to Ovid, sources from throughout the ancient world show authors exercising both imagination and observation in the description of these creatures. Mythology as well played a large role in the creation of these beliefs, with such classic examples as Perseus and Andromeda or Herakles and Hesione. -

A Language-Exercise in Dramatization

A LANGUAGE-EXERCISE IN DRAMATIZATION EMMA SIEBEL No material presented for a language-exercise and no form of language-work has awakened in the children a more intense interest or provoked them to greater effort than have the stories of the gods and the Trojan war, and especially the writing of the play which follows. The exercise is classwork, and all the children are represented, some contributing more than others; all, however, working with earnestness and each doing his part. There was quite a heated discussion as to the subject to be chosen-some favoring the "Wedding Feast," others contending that that would be too simple, that it would only necessitate allow- ing the characters to say "in their own words" what the story had told them. They wished to "make up" their play, and the suggestion that we write on "Laomedon's Broken Promises," that being a story from which "a good lesson could be learned," carried the day. I had some misgivings as to the outcome, but would not discourage their enthusiastic effort. The story of Cinderella, so familiar to all, was acted out to give them the "play-idea" and to familiarize them with the terms "exit," "enter," "act," "scene," "speech," "action," etc. We then spent one lesson "practicing," as they said, "the language of the gods," and another in changing sentences, "to make them sound more poetical." The suggestion to substitute "Persons of the Play" for "Cast of Characters" came from a little girl who thought that "we are only children, and we want it to be all our own." They then selected the characters needed, deciding that we could easily add others should we have need of them. -

Literary Industries

Literary industries By Hubert Howe Bancroft NATIVE RACES OF THE PACIFIC STATES; five volumes HISTORY OF CENTRAL AMERICA; three volumes HISTORY OF MEXICO; six volumes HISTORY OF TEXAS AND THE NORTH MEXICAN STATES; two volumes HISTORY OF ARIZONA AND NEW MEXICO; one volume HISTORY OF CALIFORNIA; seven volumes HISTORY OF NEVADA, COLORADO AND WYOMING; one volume HISTORY OF UTAH; one volume HISTORY OF THE NORTHWEST COAST; two volumes HISTORY OF OREGON; two volumes HISTORY OF WASHINGTON, IDAHO AND MONTANA; one volume HISTORY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA; one volume HISTORY OF ALASKA; one volume CALIFORNIA PASTORAL; one volume CALIFORNIA INTER-POCULA; one volume Literary industries http://www.loc.gov/resource/calbk.195 POPULAR TRIBUNALS; two volumes ESSAYS AND MISCELLANY; one volume LITERARY INDUSTRIES; one volume CHRONICLES OF THE BUILDERS OF THE COMMONWEALTH LITERARY INDUSTRIES. A MEMOIR. BY HUBERT HOWE BANCROFT All my life I have followed few and simple aims, but I have always known my own purpose clearly, and that is a source of infinite strength. William Waldorf Astor. SAN FRANCISCO THE HISTORY COMPANY, PUBLISHERS 1891 Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1890, by HUBERT H. BANCROFT, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. Literary industries http://www.loc.gov/resource/calbk.195 All Rights Reserved. v CONTENTS OF THIS VOLUME. CHAPTER I. PAGE. THE FIELD 1 CHAPTER II. THE ATMOSPHERE 12 CHAPTER III. SPRINGS AND LITTLE BROOKS 42 CHAPTER IV. THE COUNTRY BOY BECOMES A BOOKSELLER 89 CHAPTER V. HAIL CALIFORNIA! ESTO PERPETUA 120 CHAPTER VI. THE HOUSE OF H. H. BANCROFT AND COMPANY 142 CHAPTER VII. -

Folktale Types and Motifs in Greek Heroic Myth Review P.11 Morphology of the Folktale, Vladimir Propp 1928 Heroic Quest

Mon Feb 13: Heracles/Hercules and the Greek world Ch. 15, pp. 361-397 Folktale types and motifs in Greek heroic myth review p.11 Morphology of the Folktale, Vladimir Propp 1928 Heroic quest NAME: Hera-kleos = (Gk) glory of Hera (his persecutor) >p.395 Roman name: Hercules divine heritage and birth: Alcmena +Zeus -> Heracles pp.362-5 + Amphitryo -> Iphicles Zeus impersonates Amphityron: "disguised as her husband he enjoyed the bed of Alcmena" “Alcmena, having submitted to a god and the best of mankind, in Thebes of the seven gates gave birth to a pair of twin brothers – brothers, but by no means alike in thought or in vigor of spirit. The one was by far the weaker, the other a much better man, terrible, mighty in battle, Heracles, the hero unconquered. Him she bore in submission to Cronus’ cloud-ruling son, the other, by name Iphicles, to Amphitryon, powerful lancer. Of different sires she conceived them, the one of a human father, the other of Zeus, son of Cronus, the ruler of all the gods” pseudo-Hesiod, Shield of Heracles Hera tries to block birth of twin sons (one per father) Eurystheus born on same day (Hera heard Zeus swear that a great ruler would be born that day, so she speeded up Eurystheus' birth) (Zeus threw her out of heaven when he realized what she had done) marvellous infancy: vs. Hera’s serpents Hera, Heracles and the origin of the MIlky Way Alienation: Madness of Heracles & Atonement pp.367,370 • murders wife Megara and children (agency of Hera) Euripides, Heracles verdict of Delphic oracle: must serve his cousin Eurystheus, king of Mycenae -> must perform 12 Labors (‘contests’) for Eurystheus -> immortality as reward The Twelve Labors pp.370ff. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

The Roman House As Memory Theater: the House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii Author(S): Bettina Bergmann Source: the Art Bulletin, Vol

The Roman House as Memory Theater: The House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii Author(s): Bettina Bergmann Source: The Art Bulletin, Vol. 76, No. 2 (Jun., 1994), pp. 225-256 Published by: College Art Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3046021 Accessed: 18-01-2018 19:09 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms College Art Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Art Bulletin This content downloaded from 132.229.13.63 on Thu, 18 Jan 2018 19:09:34 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms The Roman House as Memory Theater: The House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii Bettina Bergmann Reconstructions by Victoria I Memory is a human faculty that readily responds to training reading and writing; he stated that we use places as wax and and can be structured, expanded, and enriched. Today few, images as letters.2 Although Cicero's analogy had been a if any, of us undertake a systematic memory training. In common topos since the fourth century B.c., Romans made a many premodern societies, however, memory was a skill systematic memory training the basis of an education. -

To Oral History

100 E. Main St. [email protected] Ventura, CA 93001 (805) 653-0323 x 320 QUARTERLY JOURNAL SUBJECT INDEX About the Index The index to Quarterly subjects represents journals published from 1955 to 2000. Fully capitalized access terms are from Library of Congress Subject Headings. For further information, contact the Librarian. Subject to availability, some back issues of the Quarterly may be ordered by contacting the Museum Store: 805-653-0323 x 316. A AB 218 (Assembly Bill 218), 17/3:1-29, 21 ill.; 30/4:8 AB 442 (Assembly Bill 442), 17/1:2-15 Abadie, (Señor) Domingo, 1/4:3, 8n3; 17/2:ABA Abadie, William, 17/2:ABA Abbott, Perry, 8/2:23 Abella, (Fray) Ramon, 22/2:7 Ablett, Charles E., 10/3:4; 25/1:5 Absco see RAILROADS, Stations Abplanalp, Edward "Ed," 4/2:17; 23/4:49 ill. Abraham, J., 23/4:13 Abu, 10/1:21-23, 24; 26/2:21 Adams, (rented from Juan Camarillo, 1911), 14/1:48 Adams, (Dr.), 4/3:17, 19 Adams, Alpha, 4/1:12, 13 ph. Adams, Asa, 21/3:49; 21/4:2 map Adams, (Mrs.) Asa (Siren), 21/3:49 Adams Canyon, 1/3:16, 5/3:11, 18-20; 17/2:ADA Adams, Eber, 21/3:49 Adams, (Mrs.) Eber (Freelove), 21/3:49 Adams, George F., 9/4:13, 14 Adams, J. H., 4/3:9, 11 Adams, Joachim, 26/1:13 Adams, (Mrs.) Mable Langevin, 14/1:1, 4 ph., 5 Adams, Olen, 29/3:25 Adams, W. G., 22/3:24 Adams, (Mrs.) W. -

The Horse-Breeder's Guide and Hand Book

LIBRAKT UNIVERSITY^' PENNSYLVANIA FAIRMAN ROGERS COLLECTION ON HORSEMANSHIP (fop^ U Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/horsebreedersguiOObruc TSIE HORSE-BREEDER'S GUIDE HAND BOOK. EMBRACING ONE HUNDRED TABULATED PEDIGREES OF THE PRIN- CIPAL SIRES, WITH FULL PERFORMANCES OF EACH AND BEST OF THEIR GET, COVERING THE SEASON OF 1883, WITH A FEW OF THE DISTINGUISHED DEAD ONES. By S. D. BRUCE, A.i3.th.or of tlie Ainerican. Stud Boole. PUBLISHED AT Office op TURF, FIELD AND FARM, o9 & 41 Park Row. 1883. NEW BOLTON CSNT&R Co 2, Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1883, By S. D. Bruce, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. INDEX c^ Stallions Covering in 1SS3, ^.^ WHOSE PEDIGREES AND PERFORMANCES, &c., ARE GIVEN IN THIS WORK, ALPHABETICALLY ARRANGED, PAGES 1 TO 181, INCLUSIVE. PART SECOISTD. DEAD SIRES WHOSE PEDIGREES AND PERFORMANCES, &c., ARE GIVEN IN THIS WORK, PAGES 184 TO 205, INCLUSIVE, ALPHA- BETICALLY ARRANGED. Index to Sires of Stallions described and tabulated in tliis volume. PAGE. Abd-el-Kader Sire of Algerine 5 Adventurer Blythwood 23 Alarm Himvar 75 Artillery Kyrle Daly 97 Australian Baden Baden 11 Fellowcraft 47 Han-v O'Fallon 71 Spendthrift 147 Springbok 149 Wilful 177 Wildidle 179 Beadsman Saxon 143 Bel Demonio. Fechter 45 Billet Elias Lawrence ' 37 Volturno 171 Blair Athol. Glen Athol 53 Highlander 73 Stonehege 151 Bonnie Scotland Bramble 25 Luke Blackburn 109 Plenipo 129 Boston Lexington 199 Breadalbane. Ill-Used 85 Citadel Gleuelg... -

Child Abuse in Greek Mythology: a Review C Stavrianos, I Stavrianou, P Kafas

The Internet Journal of Forensic Science ISPUB.COM Volume 3 Number 1 Child Abuse in Greek Mythology: A Review C Stavrianos, I Stavrianou, P Kafas Citation C Stavrianos, I Stavrianou, P Kafas. Child Abuse in Greek Mythology: A Review. The Internet Journal of Forensic Science. 2007 Volume 3 Number 1. Abstract The aim of this review was to describe child abuse cases in ancient Greek mythology. Names like Hercules, Saturn, Aesculapius, Medea are very familiar. The stories can be divided into 3 categories: child abuse from gods to gods, from gods to humans and from humans to humans. In these stories children were abused in different ways and the reasons were of social, financial, political, religious, medical and sexual origin. The interpretations of the myths differed and the conclusions seemed controversial. Archaeologists, historians, and philosophers still try to bring these ancient stories into light in connection with the archaeological findings. The possibility for a dentist to face a child abuse case in the dental office nowadays proved the fact that child abuse was not only a phenomenon of the past but also a reality of the present. INTRODUCTION courses are easily available to everyone. Child abuse may be defined as any non-accidental trauma, On 1860 the forensic odontologist Ambroise Tardieu, neglect, failure to meet basic needs or abuse inflicted upon a referring to 32 cases, made a connection between subdural child by a caretaker that is beyond the acceptable norm of haematoma and abuse. In 1874 a church group in New York childcare in our culture. Abused children found in all 1 City took a child named Mary-Helen from home in which economic, social, ethnic and cultural backgrounds and she was being abused. -

Fasig-Tipton

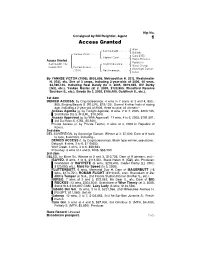

Hip No. Consigned by Bill Reightler, Agent 1 Access Granted Halo Saint Ballado . { Ballade Yankee Victor . Caro (IRE) { Highest Carol . { Tokyo Princess Access Granted . Fappiano Dark bay/br. filly; Cryptoclearance . { Naval Orange foaled 2002 {Denied Access . Sovereign Dancer (1992) { Del Sovereign . { Delso By YANKEE VICTOR (1996), $833,806, Metropolitan H. [G1], Westchester H. [G3], etc. Sire of 3 crops, including 2-year-olds of 2006, 40 wnrs, $2,490,140, including Real Dandy (to 3, 2005, $819,935, WV Derby [G3], etc.), Yankee Master (at 2, 2005, $123,900, Woodford Reserve Bourbon S., etc.), Swede (to 3, 2005, $106,400, Goldfinch S., etc.). 1st dam DENIED ACCESS, by Cryptoclearance. 4 wins in 7 starts at 3 and 4, $53,- 865, Singing Beauty S. [R] (LRL, $19,125). Dam of 4 other foals of racing age, including a 2-year-old of 2006, three to race, all winners-- Access Agenda (g. by Twilight Agenda). 8 wins, 2 to 7, 2005, $203,735, 2nd Mister Diz S.-R (LRL, $10,000). Access Approved (g. by With Approval). 11 wins, 4 to 6, 2005, $181,591, 3rd Da Hoss S. (CNL, $5,500). Private Access (c. by Private Terms). 2 wins at 4, 2005 in Republic of Korea. 2nd dam DEL SOVEREIGN, by Sovereign Dancer. Winner at 2, $7,500. Dam of 9 foals to race, 8 winners, including-- DENIED ACCESS (f. by Cryptoclearance). Black type winner, see above. Delquoit. 8 wins, 2 to 6, $119,653. Wolf Creek. 4 wins, 3 to 6, $58,683. Provobay. 3 wins at 4 and 5, 2005, $55,900.