The Customization of Wall Painting Designs in the Roman Domus: a Case Study of the Trojan Cycle Friezes of Pompeii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

The Horse-Breeder's Guide and Hand Book

LIBRAKT UNIVERSITY^' PENNSYLVANIA FAIRMAN ROGERS COLLECTION ON HORSEMANSHIP (fop^ U Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/horsebreedersguiOObruc TSIE HORSE-BREEDER'S GUIDE HAND BOOK. EMBRACING ONE HUNDRED TABULATED PEDIGREES OF THE PRIN- CIPAL SIRES, WITH FULL PERFORMANCES OF EACH AND BEST OF THEIR GET, COVERING THE SEASON OF 1883, WITH A FEW OF THE DISTINGUISHED DEAD ONES. By S. D. BRUCE, A.i3.th.or of tlie Ainerican. Stud Boole. PUBLISHED AT Office op TURF, FIELD AND FARM, o9 & 41 Park Row. 1883. NEW BOLTON CSNT&R Co 2, Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1883, By S. D. Bruce, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. INDEX c^ Stallions Covering in 1SS3, ^.^ WHOSE PEDIGREES AND PERFORMANCES, &c., ARE GIVEN IN THIS WORK, ALPHABETICALLY ARRANGED, PAGES 1 TO 181, INCLUSIVE. PART SECOISTD. DEAD SIRES WHOSE PEDIGREES AND PERFORMANCES, &c., ARE GIVEN IN THIS WORK, PAGES 184 TO 205, INCLUSIVE, ALPHA- BETICALLY ARRANGED. Index to Sires of Stallions described and tabulated in tliis volume. PAGE. Abd-el-Kader Sire of Algerine 5 Adventurer Blythwood 23 Alarm Himvar 75 Artillery Kyrle Daly 97 Australian Baden Baden 11 Fellowcraft 47 Han-v O'Fallon 71 Spendthrift 147 Springbok 149 Wilful 177 Wildidle 179 Beadsman Saxon 143 Bel Demonio. Fechter 45 Billet Elias Lawrence ' 37 Volturno 171 Blair Athol. Glen Athol 53 Highlander 73 Stonehege 151 Bonnie Scotland Bramble 25 Luke Blackburn 109 Plenipo 129 Boston Lexington 199 Breadalbane. Ill-Used 85 Citadel Gleuelg... -

Fasig-Tipton

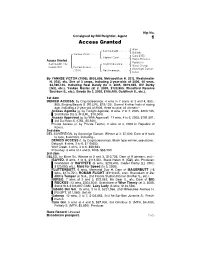

Hip No. Consigned by Bill Reightler, Agent 1 Access Granted Halo Saint Ballado . { Ballade Yankee Victor . Caro (IRE) { Highest Carol . { Tokyo Princess Access Granted . Fappiano Dark bay/br. filly; Cryptoclearance . { Naval Orange foaled 2002 {Denied Access . Sovereign Dancer (1992) { Del Sovereign . { Delso By YANKEE VICTOR (1996), $833,806, Metropolitan H. [G1], Westchester H. [G3], etc. Sire of 3 crops, including 2-year-olds of 2006, 40 wnrs, $2,490,140, including Real Dandy (to 3, 2005, $819,935, WV Derby [G3], etc.), Yankee Master (at 2, 2005, $123,900, Woodford Reserve Bourbon S., etc.), Swede (to 3, 2005, $106,400, Goldfinch S., etc.). 1st dam DENIED ACCESS, by Cryptoclearance. 4 wins in 7 starts at 3 and 4, $53,- 865, Singing Beauty S. [R] (LRL, $19,125). Dam of 4 other foals of racing age, including a 2-year-old of 2006, three to race, all winners-- Access Agenda (g. by Twilight Agenda). 8 wins, 2 to 7, 2005, $203,735, 2nd Mister Diz S.-R (LRL, $10,000). Access Approved (g. by With Approval). 11 wins, 4 to 6, 2005, $181,591, 3rd Da Hoss S. (CNL, $5,500). Private Access (c. by Private Terms). 2 wins at 4, 2005 in Republic of Korea. 2nd dam DEL SOVEREIGN, by Sovereign Dancer. Winner at 2, $7,500. Dam of 9 foals to race, 8 winners, including-- DENIED ACCESS (f. by Cryptoclearance). Black type winner, see above. Delquoit. 8 wins, 2 to 6, $119,653. Wolf Creek. 4 wins, 3 to 6, $58,683. Provobay. 3 wins at 4 and 5, 2005, $55,900. -

2018 Media Guide NYRA.Com 1 FIRST RUNNING the First Running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park Took Place on a Thursday

2018 Media Guide NYRA.com 1 FIRST RUNNING The first running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park took place on a Thursday. The race was 1 5/8 miles long and the conditions included “$200 each; half forfeit, and $1,500-added. The second to receive $300, and an English racing saddle, made by Merry, of St. James TABLE OF Street, London, to be presented by Mr. Duncan.” OLDEST TRIPLE CROWN EVENT CONTENTS The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is the oldest of the Triple Crown events. It predates the Preakness Stakes (first run in 1873) by six years and the Kentucky Derby (first run in 1875) by eight. Aristides, the winner of the first Kentucky Derby, ran second in the 1875 Belmont behind winner Calvin. RECORDS AND TRADITIONS . 4 Preakness-Belmont Double . 9 FOURTH OLDEST IN NORTH AMERICA Oldest Triple Crown Race and Other Historical Events. 4 Belmont Stakes Tripped Up 19 Who Tried for Triple Crown . 9 The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is one of the oldest stakes races in North America. The Phoenix Stakes at Keeneland was Lowest/Highest Purses . .4 How Kentucky Derby/Preakness Winners Ran in the Belmont. .10 first run in 1831, the Queens Plate in Canada had its inaugural in 1860, and the Travers started at Saratoga in 1864. However, the Belmont, Smallest Winning Margins . 5 RUNNERS . .11 which will be run for the 150th time in 2018, is third to the Phoenix (166th running in 2018) and Queen’s Plate (159th running in 2018) in Largest Winning Margins . -

Heracles on Top of Troy in the Casa Di Octavius Quartio in Pompeii Katharina Lorenz

9 | Split-screen visions: Heracles on top of Troy in the Casa di Octavius Quartio in Pompeii katharina lorenz The houses of Pompeii are full of mythological images, several of which present scenes of Greek, few of Roman epic.1 Epic visions, visual experi- ences derived from paintings featuring epic story material, are, therefore, a staple feature in the domestic sphere of the Campanian town throughout the late first century BCE and the first century CE until the destruction of the town in 79 CE. The scenes of epic, and mythological scenes more broadly, profoundly undercut the notion that such visualisations are merely illustration of a textual manifestation; on the contrary: employing a diverse range of narrative strategies and accentuations, they elicit content exclusive to the visual domain, and rub up against the conventional, textual classifications of literary genres. The media- and genre-transgressing nature of Pompeian mythological pictures renders them an ideal corpus of material to explore what the relationships are between visual representations of epic and epic visions, what characterises the epithet ‘epic’ when transferred to the visual domain, and whether epic visions can only be generated by stories which the viewer associates with a text or texts of the epic genre. One Pompeian house in particular provides a promising framework to study this: the Casa di Octavius Quartio, which in one of its rooms combines two figure friezes in what is comparable to the modern cinematographic mode of the split screen. Modern study has been reluctant to discuss these pictures together,2 1 Vitruvius (7.5.2) differentiates between divine, mythological and Homeric decorations, emphasising the special standing of Iliad and Odyssey in comparison to the overall corpus of mythological depictions; cf. -

John Ferneley Catalogue of Paintings

JOHN FERNELEY (1782 – 1860) CATALOGUE OF PAINTINGS CHRONOLOGICALLY BY SUBJECT Compiled by R. Fountain Updated December 2014 1 SUBJECT INDEX Page A - Country Life; Fairs; Rural Sports, Transport and Genre. 7 - 11 D - Dogs; excluding hounds hunting. 12 - 23 E - Horses at Liberty. 24 - 58 G - Horses with grooms and attendants (excluding stabled horses). 59 - 64 H - Portraits of Gentlemen and Lady Riders. 65 - 77 J - Stabled Horses. 74 - 77 M - Military Subjects. 79 P - Hunting; Hunts and Hounds. 80 - 90 S - Shooting. 91 - 93 T - Portraits of Racehorses, Jockeys, Trainers and Races. 94 - 99 U - Portraits of Individuals and Families (Excluding equestrian and sporting). 100 - 104 Index of Clients 105 - 140 2 NOTES ON INDEX The basis of the index are John Ferneley’s three account books transcribed by Guy Paget and published in the latter’s book The Melton Mowbray of John Ferneley, 1931. There are some caveats; Ferneley’s writing was always difficult to read, the accounts do not start until 1808, are incomplete for his Irish visits 1809-1812 and pages are missing for entries in the years 1820-1826. There are also a significant number of works undoubtedly by John Ferneley senior that are not listed (about 15-20%) these include paintings that were not commissioned or sold, those painted for friends and family and copies. A further problem arises with unlisted paintings which are not signed in full ie J. Ferneley/Melton Mowbray/xxxx or J. Ferneley/pinxt/xxxx but only with initials, J. Ferneley/xxxx, or not at all. These paintings may be by John Ferneley junior or Claude Loraine Ferneley whose work when at its best is difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish from that of their father or may be by either son with the help of their father. -

AP® Latin Teaching the Aeneid

Professional Development AP® Latin Teaching The Aeneid Curriculum Module The College Board The College Board is a mission-driven not-for-profit organization that connects students to college success and opportunity. Founded in 1900, the College Board was created to expand access to higher education. Today, the membership association is made up of more than 5,900 of the world’s leading educational institutions and is dedicated to promoting excellence and equity in education. Each year, the College Board helps more than seven million students prepare for a successful transition to college through programs and services in college readiness and college success — including the SAT® and the Advanced Placement Program®. The organization also serves the education community through research and advocacy on behalf of students, educators and schools. For further information, visit www.collegeboard.org. © 2011 The College Board. College Board, Advanced Placement Program, AP, AP Central, SAT, and the acorn logo are registered trademarks of the College Board. All other products and services may be trademarks of their respective owners. Visit the College Board on the Web: www.collegeboard.org. Contents Introduction................................................................................................. 1 Jill Crooker Minor Characters in The Aeneid...........................................................3 Donald Connor Integrating Multiple-Choice Questions into AP® Latin Instruction.................................................................... -

D. Octavius Caesar Augustus (Augustus) - the Lives of the Twelve Caesars, Volume 2

D. Octavius Caesar Augustus (Augustus) - The Lives Of The Twelve Caesars, Volume 2. C. Suetonius Tranquillus Project Gutenberg's D. Octavius Caesar Augustus, (Augustus) by C. Suetonius Tranquillus This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: D. Octavius Caesar Augustus (Augustus) The Lives Of The Twelve Caesars, Volume 2. Author: C. Suetonius Tranquillus Release Date: December 13, 2004 [EBook #6387] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK D. OCTAVIUS CAESAR AUGUSTUS *** Produced by Tapio Riikonen and David Widger THE LIVES OF THE TWELVE CAESARS By C. Suetonius Tranquillus; To which are added, HIS LIVES OF THE GRAMMARIANS, RHETORICIANS, AND POETS. The Translation of Alexander Thomson, M.D. revised and corrected by T.Forester, Esq., A.M. Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. D. OCTAVIUS CAESAR AUGUSTUS. (71) I. That the family of the Octavii was of the first distinction in Velitrae [106], is rendered evident by many circumstances. For in the most frequented part of the town, there was, not long since, a street named the Octavian; and an altar was to be seen, consecrated to one Octavius, who being chosen general in a war with some neighbouring people, the enemy making a sudden attack, while he was sacrificing to Mars, he immediately snatched the entrails of the victim from off the fire, and offered them half raw upon the altar; after which, marching out to battle, he returned victorious. -

2020 International List of Protected Names

INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (only available on IFHA Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 03/06/21 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne-Billancourt, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org The list of Protected Names includes the names of : Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally renowned, either as main stallions and broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or jump) From 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf Since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf The main stallions and broodmares, registered on request of the International Stud Book Committee (ISBC). Updates made on the IFHA website The horses whose name has been protected on request of a Horseracing Authority. Updates made on the IFHA website * 2 03/06/2021 In 2020, the list of Protected -

2019 Media Guide NYRA.Com 1 TABLE of CONTENTS

2019 Media Guide NYRA.com 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS HISTORY 2 Table of Conents 3 General Information 4 History of The New York Racing Association, Inc. (NYRA) 5 NYRA Officers and Officials 6 Belmont Park History 7 Belmont Park Specifications & Map 8 Saratoga Race Course History 9 Saratoga Leading Jockeys and Trainers TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE 10 Saratoga Race Course Specifications & Map 11 Saratoga Walk of Fame 12 Aqueduct Racetrack History 13 Aqueduct Racetrack Specifications & Map 14 NYRA Bets 15 Digital NYRA 16-17 NYRA Personalities & NYRA en Espanol 18 NYRA & Community/Cares 19 NYRA & Safety 20 Handle & Attendance Page OWNERS 21-41 Owner Profiles 42 2018 Leading Owners TRAINERS 43-83 Trainer Profiles 84 Leading Trainers in New York 1935-2018 85 2018 Trainer Standings JOCKEYS 85-101 Jockey Profiles 102 Jockeys that have won six or more races in one day 102 Leading Jockeys in New York (1941-2018) 103 2018 NYRA Leading Jockeys BELMONT STAKES 106 History of the Belmont Stakes 113 Belmont Runners 123 Belmont Owners 132 Belmont Trainers 138 Belmont Jockeys 144 Triple Crown Profiles TRAVERS STAKES 160 History of the Travers Stakes 169 Travers Owners 173 Travers Trainers 176 Travers Jockeys 29 The Whitney 2 2019 Media Guide NYRA.com AQUEDUCT RACETRACK 110-00 Rockaway Blvd. South Ozone Park, NY 11420 2019 Racing Dates Winter/Spring: January 1 - April 20 BELMONT PARK 2150 Hempstead Turnpike Elmont, NY, 11003 2019 Racing Dates Spring/Summer: April 26 - July 7 GENERAL INFORMATION GENERAL SARATOGA RACE COURSE 267 Union Ave. Saratoga Springs, NY, 12866 -

CHAPTERS from TURF HISTORY "By U^EWMARKET 2-7

CHAPTERS FROM TURF HISTORY "By U^EWMARKET 2-7 JOHNA.SEAVERNS TUFTS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES 3 9090 014 540 286 Webster Family Library of Veterinary Medicine Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University 200 Westboro Road North Grafton. MA 01535 CHAPTERS FROM TURF HISTORY The Two CHAPTERS FROM TURF HISTORY BY NEWMARKET LONDON "THE NATIONAL REVIEW" OFFICE 43 DUKE STREET, ST. JAMES'S. S.W.I 1922 '"^1"- 6 5f \^n The author desires to make due acknowledgment to Mr. Maxse, Editor of the National Review, for permission to reprint the chapters of this book which first appeared under his auspices. CONTENTS PAGK I. PRIME MINISTERS AND THEIR RACE-HORSES II II. A GREAT MATCH (VOLTIGEUR AND THE FLYING DUTCHMAN) . -44 III. DANEBURY AND LORD GEORGE BENTINCK . 6l IV. THE RING, THE TURF, AND PARLIAMENT (MR. GULLY, M.P.) . .86 V. DISRAELI AND THE RACE-COURSE . IO3 VI. THE FRAUD OF A DERBY .... I26 VII. THE TURF AND SOME REFLECTIONS . I44 ILLUSTRATIONS THE 4TH DUKE OF GRAFTON .... Frontispiece TO FACE PAGE THE 3RD DUKE OF GRAFTON, FROM AN OLD PRINT . 22 THE DEFEAT OF CANEZOU IN THE ST. LEGER ... 35 BLUE BONNET, WINNER OF THE ST. LEGER, 1842 . 45 THE FLYING DUTCHMAN, WINNER OF THE DERBY AND THE ST. LEGER, 1849 .48 VOLTIGEUR, WINNER OF THE DERBY AND THE ST. LEGER, 1850 50 THE DONCASTER CUP, 1850. VOLTIGEUR BEATING THE FLYING DUTCHMAN 54 trainer's COTTAGE AT DANEBURY IN THE TIME OF OLD JOHN DAY 62 THE STOCKBRIDGE STANDS 62 LORD GEORGE BENTINCK, AFTER THE DRAWING BY COUNT d'orsay 64 TRAINER WITH HORSES ON STOCKBRIDGE RACE-COURSE . -

Famous Racing

FAMOUS RACING TALES OF THE \«L."-- waster Family Library of Veterinary N/tedic<ne Cummirigs School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University 200 Westtx)ro Road North Grafton. MA 01S36 .TUFTS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES 3 9090 014 561 241 [PRICE ONE SHILLING.] ^" A Little Book for Every Holder of Consols and for every Counting-House and Private Desk in the Land. TALES PLEASANT AND TRAGIC OF THE BANK OF ENGLAND, ITS FAITHFUL AND UNTKUE SERVANTS, ANCIENT FOES AND TIME-TRIED FRIENDS, CLOSE PINCHES AND NARROW ESCAPES; WITH PORTRAITS AND ANECDOTES OF THE FOUNDER OF THE BANK—THE OLD BANKERS, CITY CELEBRITIES AND MERCHANTS; GRESHAM AND THE CITY GRASSHOPPER; MARTINS, CHILDS, ROTHSCHILDS, BARINGS, COUTTS, THE GOLDSMIDS, &c. WARD'S PICTURE OF "THE SOUTH SEA BUBBLE."—THE ROMAXCE OF BANKING.—THE PATTERN CASHIER. NOTABILIA OF FORGERIES.-CURIOSITIES OF BANK NOTES, &c. BY A HANDMAID THE OLD LADY OF THREADNEEDLE STREET. LONDON .—JAMES HOGG, 22, EXETER STREET, STRAND. LORD GEORGE BENTINCK. (Sn- pm/c m.) — " J FAMOUS RACING MEN WITH ANECDOTES AND PORTRAITS. By 'THORMANBY.' In life's rough tide I sank not down, But swam till Fortune threw a rope, Buoyant on bladders filled with hope." Green. ( T/te Spleen. " Nee metuis dubio Fortunte stantis in orbe Numen, et exosa- verba superba decc ? " Fearest thou not the divine power of Fortune, as she stands on her unsteady wheel, that gfoddess who abhors all vaunting words ? "--OviD. LONDON: JAMES HOGG, 22, EXETER STREET, STRAND, W.C. 1882. ^4,C^\3 WITH A FRONTISPIECE SHOWING THE HAND OF GOOD FORTUNE! Crown 8vo., price 3s. 6d.