Famous Racing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Fast Horses The Racehorse in Health, Disease and Afterlife, 1800 - 1920 Harper, Esther Fiona Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 10. Oct. 2021 Fast Horses: The Racehorse in Health, Disease and Afterlife, 1800 – 1920 Esther Harper Ph.D. History King’s College London April 2018 1 2 Abstract Sports historians have identified the 19th century as a period of significant change in the sport of horseracing, during which it evolved from a sporting pastime of the landed gentry into an industry, and came under increased regulatory control from the Jockey Club. -

The Tyro a Review of the Arts of Painting Sculptore and Design

THE TYRO A REVIEW OF THE ARTS OF PAINTING SCULPTORE AND DESIGN. EDITED BY WYNDHAM LEWIS. TO BE PRODUCED AT INTERVALS OF TWO OR THREE MONTHS. Publishers : THE EGOIST PRESS, 2, ROBERT STREET, ADELPH1. PUBLISHED AT 1s. 6d, Subscription for 4 numbers, 6s. 6d, with postage. Printed by Bradley & Son, Ltd., Little Crown Yard, Mill Lane, Reading. NOTE ON TYROS. We present to you in this number the pictures of several very powerful Tyros.* These immense novices brandish their appetites in their faces, lay bare their teeth in a valedictory, inviting, or merely substantial laugh. A. laugh, like a sneeze, exposes the nature of the individual with an unexpectedness that is perhaps a little unreal. This sunny commotion in the face, at the gate of the organism, brings to the surface all the burrowing and interior broods which the individual may harbour. Understanding this so well, people hatch all their villainies in this seductive glow. Some of these Tyros are trying to furnish you with a moment of almost Mediterranean sultriness, in order, in this region of engaging warmth, to obtain some advantage over you. But most of them are, by the skill of the artist, seen basking themselves in the sunshine of their own abominable nature. These partly religious explosions of laughing Elementals are at once satires, pictures, and stories The action of a Tyro is necessarily very restricted; about that of a puppet worked with deft fingers, with a screaming voice underneath. There is none" of the pathos of Pagliacci in the story of the Tyro. It is the child in him that has risen in his laugh, and you get a perspective of his history. -

Le Harcèlement Sexuel : Clarification

Université de Montréal L’évolution des représentations des crimes sexuels et du harcèlement sexuel dans les téléséries américaines de fiction post #Metoo. Par Françoise Goulet-Pelletier Département d’histoire de l’art et d’études cinématographiques Faculté des arts et des sciences Mémoire présenté à la Faculté des études supérieures et postdoctorales en vue de l’obtention du grade de M.A. en études cinématographiques, option recherche. Décembre 2019 © Françoise Goulet-Pelletier, 2019 ii Université de Montréal Unité académique : Département d’histoire de l’art et d’études cinématographiques Ce mémoire intitulé L’évolution des représentations des crimes sexuels et du harcèlement sexuel dans les téléséries américaines post #Metoo. Présenté par Françoise Goulet-Pelletier A été évalué par un jury composé des personnes suivantes Isabelle Raynauld Directrice de recherche Marta Boni Membre du jury Stéfany Boisvert Membre du jury iii Résumé Le mouvement social #Metoo a bouleversé les mœurs et les façons de penser quant aux enjeux liés au harcèlement sexuel et aux abus sexuels. En effet, en automne 2017, une vague de dénonciations déferle sur la place publique et peu à peu, les frontières de ce qui est acceptable ou pas semblent se redéfinir au sein de plusieurs sociétés. En partant de cette constatation sociétale, nous avons cru remarquer une reprise des enjeux entourant le mouvement social #Metoo dans les séries télévisées américaines de fiction. Ce mémoire souhaite illustrer et analyser l’évolution des représentations des crimes sexuels et du harcèlement sexuel inspirée par le mouvement #Metoo. En reprenant les grandes lignes de ce mouvement, cette étude s’attarde sur son impact sur la société nord-américaine. -

Visions of Vietnam

DATA BOOK STAKES RESULTS European Pattern 2008 : HELLEBORINE (f Observatory) 3 wins at 2, wins in USA, Mariah’s Storm S, 2nd Gardenia H G3 . 277 PARK HILL S G2 Prix d’Aumale G3 , Prix Six Perfections LR . 280 DONCASTER CUP G2 Dam of 2 winners : 2010 : (f Observatory) 2005 : CONCHITA (f Cozzene) Winner at 3 in USA. DONCASTER. Sep 9. 3yo+f&m. 14f 132yds. DONCASTER. September 10. 3yo+. 18f. 2006 : Towanda (f Dynaformer) 1. EASTERN ARIA (UAE) 4 9-4 £56,770 2nd Dam : MUSICANTI by Nijinsky. 1 win in France. 1. SAMUEL (GB) 6 9-1 £56,770 2008 : WHITE MOONSTONE (f Dynaformer) 4 wins b f by Halling - Badraan (Danzig) Dam of DISTANT MUSIC (c Distant View: Dewhurst ch g by Sakhee - Dolores (Danehill) at 2, Meon Valley Stud Fillies’ Mile S G1 , O- Sheikh Hamdan Bin Mohammed Al Maktoum S G1 , 3rd Champion S G1 ), New Orchid (see above) O/B- Normandie Stud Ltd TR- JHM Gosden Keepmoat May Hill S G2 , germantb.com Sweet B- Darley TR- M Johnston 2. Tastahil (IRE) 6 9-1 £21,520 Solera S G3 . 2. Rumoush (USA) 3 8-6 £21,520 Broodmare Sire : QUEST FOR FAME . Sire of the ch g by Singspiel - Luana (Shaadi) 2009 : (f Arch) b f by Rahy - Sarayir (Mr Prospector) dams of 24 Stakes winners. In 2010 - SKILLED O- Hamdan Al Maktoum B- Darley TR- BW Hills 2010 : (f Tiznow) O- Hamdan Al Maktoum B- Shadwell Farm LLC Commands G1, TAVISTOCK Montjeu G1, SILVER 3. Motrice (GB) 3 7-12 £10,770 TR- MP Tregoning POND Act One G2, FAMOUS NAME Dansili G3, gr f by Motivator - Entente Cordiale (Affirmed) 2nd Dam : DESERT STORMETTE by Storm Cat. -

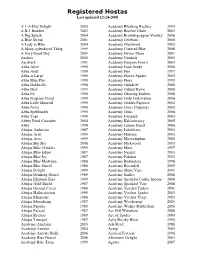

Registered Hostas Last Updated 12-24-2008

Registered Hostas Last updated 12-24-2008 A 1-A-Day Delight 2003 Academy Blushing Recluse 1999 A B-1 Bomber 2002 Academy Bonfire Glade 2003 A Big Splash 2004 Academy Brobdingnagian Viridity 2006 A Blue Streak 2001 Academy Celeborn 2000 A Lady in Blue 2004 Academy Chetwood 2005 A Many-splendored Thing 1999 Academy Cratered Blue 2008 A Very Good Boy 2005 Academy Devon Moor 2001 Aachen 2005 Academy Dimholt 2005 Aardvark 1991 Academy Fangorn Forest 2003 Abba Alive 1990 Academy Faux Sedge 2008 Abba Aloft 1990 Academy Fire 1997 Abba at Large 1990 Academy Flaxen Spades 2002 Abba Blue Plus 1990 Academy Flora 1999 Abba Dabba Do 1998 Academy Galadriel 2000 Abba Dew 1999 Academy Gilded Dawn 2008 Abba Fit 1990 Academy Glowing Embers 2008 Abba Fragrant Cloud 1990 Academy Gold Codswallop 2006 Abba Little Showoff 1990 Academy Golden Papoose 2004 Abba Nova 1990 Academy Grass Clippings 2005 Abba Spellbinder 1990 Academy Grins 2008 Abba Tops 1990 Academy Isengard 2003 Abbey Pond Cascades 2004 Academy Kakistocracy 2005 Abby 1990 Academy Lemon Knoll 2006 Abiqua Ambrosia 1987 Academy Lothlórien 2004 Abiqua Ariel 1999 Academy Mallorn 2003 Abiqua Aries 1999 Academy Mavrodaphne 2000 Abiqua Big Sky 2008 Academy Mirkwood 2003 Abiqua Blue Crinkles 1999 Academy Muse 1997 Abiqua Blue Edger 1987 Academy Nazgul 2003 Abiqua Blue Jay 1987 Academy Palantir 2003 Abiqua Blue Madonna 1988 Academy Redundant 1998 Abiqua Blue Shield 1988 Academy Rivendell 2005 Abiqua Delight 1999 Academy Shiny Vase 2001 Abiqua Drinking Gourd 1989 Academy Smiles 2008 Abiqua Elephant Ears 1999 -

Fivewinners for Godolphinon a Very Special Carnival Night

2 February 2017 www.aladiyat.ae ISSUE 607 Dhs 5 FIVE winners for Godolphin on a Very Special Carnival Night Two for Saeed bin Suroor Very Special (Cape Verdi) Promising Run (Al Rashidiya) Three for Charlie Appleby Gold Trail (2410m turf handicap) Fly At Dawn (UAE 2000 Guineas Trial) Baccarat (1200m turf handicap) Arrogate ‘flies home’ to land Pegasus Arrogate ‘Locals’ Le Bernardin and Muarrab among Torchlighter Meydan stars on show this Thursday Le Bernardin Muarrab Standing at Nunnery Stud, England: MAWATHEEQ MUKHADRAM NAYEF SAKHEE Also standing in England: HAAFHD Standing in France, Haras du Mezeray: MUHTATHIR Standing in Italy, Allevamento di Besnate: MUJAHID www.shadwellstud.co.uk www.shadwellstud.co.uk Discover more about the Shadwell Stallions at www.shadwellstud.co.uk Or call Richard Lancaster, Johnny Peter-Hoblyn or Rachael Gowland on 01842 755913 Email us at: [email protected] twitter.com/ShadwellStud www.facebook.com/ShadwellStud 2 February 2017 3 Godolphin firmly in charge of Contents NEWS 3-13 Carnival owners’ title, again BLOODSTOCK 14-15 EEKING to be leading SPINNING WORLD 17 owner at the Dubai World NICHOLAS GODFREY 18 Cup Carnival for a tenth HOWARD WRIGHT 19 Sconsecutive season, Godolphin JOHN BERRY 20-21 probably secured that accolade DEREK THOMPSON 22 in one foul swoop last Thursday TOM JENNINGS 23 when their famous blue silks were carried to victory on no less than MICHELE MACDONALD 24-25 five occasions, doubling their 2017 RACING STATISTICS 27 Carnival tally. THE FONZ 29 Their main trainers, Saeed bin ENDURANCE 31 Suroor, who saddled a double and HOWJUMPING 32 th S his 200 Carnival winner in the Adam Kirby Jim Crowley QATAR 33 process, and Charlie Appleby, REVIEWS / RESULTS who registered a treble, lead the Kirby, making his seasonal debut Christophe Soumillon, in the MEYDAN (THU) 34-36 way for the trainers with five and who can now boast a 100% jockeys’ table. -

Lot 1066 (100% GST)BAY OR BROWN COLT Stable B 1 Foaled 22Nd September 2018 Branded : Nr Sh; 11 Over 8 Off Sh

Account of BYERLEY STUD, Sandy Hollow, NSW. Lot 1066 (100% GST)BAY OR BROWN COLT Stable B 1 Foaled 22nd September 2018 Branded : nr sh; 11 over 8 off sh Sire Bianconi Danzig ............................. Northern Dancer NICCONI Fall Aspen .................................... Pretense 2005 Nicola Lass Scenic .................................. Sadler's Wells Dubai Lass ................................ Bletchingly Dam Statue of Liberty Storm Cat .................................. Storm Bird LADY OF LIBERTY Charming Lassie ................... Seattle Slew 2013 Export Lady Export Price .................................... Habitat Lady Violet ................................. Old Crony NICCONI (AUS) (Bay 2005-Stud 2010). 6 wins-1 at 2, VRC Lightning S., Gr.1. Sire of 423 rnrs, 311 wnrs, 18 SW, inc. SW Nature Strip (ATC Galaxy H., Gr.1), Faatinah, Sircconi, Chill Party, Nicoscene, Niccanova, Time Awaits, Concealer, Tony Nicconi, Hear the Chant, State Solicitor, Caipirinha, Nistaan, It's Been a Battle, Ayers Rock, Quatronic, Exclusive Lass, Loved Up, SP Lankan Star, Niccovi, Akkadian, Mandylion, Shokora, etc. 1st dam LADY OF LIBERTY, by Statue of Liberty. Raced twice. Three-quarter-sister to TEMPEST TOST (dam of MILDRED). This is her first foal. 2nd dam EXPORT LADY, by Export Price. 2 wins at 1200m. Sister to NOTOIRE, Violet Haze (dam of SINO BRILHANTE), half-sister to TEMPEST TOST (dam of MILDRED), WELL KNOWN, Livigno, Tullamarine, Springburn (dam of (MY) NIKITA, HAPPY HIPPY). Dam of 10 foals, 8 to race, 5 winners, inc:- Black Bubble. 6 wins 1000m to 1200m, $150,450, VRC Aluminates Chemical Industries H., MRC Gecko Solutions Training H., San Domenico H. Sneem. 6 wins-4 in succession-to 1300m, QTC Paul Carter Solicitor H. 3rd dam LADY VIOLET, by Old Crony. -

The General Stud Book : Containing Pedigrees of Race Horses, &C

^--v ''*4# ^^^j^ r- "^. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2009 witii funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/generalstudbookc02fair THE GENERAL STUD BOOK VOL. II. : THE deiterol STUD BOOK, CONTAINING PEDIGREES OF RACE HORSES, &C. &-C. From the earliest Accounts to the Year 1831. inclusice. ITS FOUR VOLUMES. VOL. II. Brussels PRINTED FOR MELINE, CANS A.ND C"., EOILEVARD DE WATERLOO, Zi. M DCCC XXXIX. MR V. un:ve PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. To assist in the detection of spurious and the correction of inaccu- rate pedigrees, is one of the purposes of the present publication, in which respect the first Volume has been of acknowledged utility. The two together, it is hoped, will form a comprehensive and tole- rably correct Register of Pedigrees. It will be observed that some of the Mares which appeared in the last Supplement (whereof this is a republication and continua- tion) stand as they did there, i. e. without any additions to their produce since 1813 or 1814. — It has been ascertained that several of them were about that time sold by public auction, and as all attempts to trace them have failed, the probability is that they have either been converted to some other use, or been sent abroad. If any proof were wanting of the superiority of the English breed of horses over that of every other country, it might be found in the avidity with which they are sought by Foreigners. The exportation of them to Russia, France, Germany, etc. for the last five years has been so considerable, as to render it an object of some importance in a commercial point of view. -

Haras La Pasion

ÍNDICE GENERAL ÍNDICE GANADORES CLÁSICOS REFERENCIA DE PADRILLOS EASING ALONG VIOLENCE MANIPULATOR LIZARD ISLAND SIXTIES ICON ZENSATIONAL SANTILLANO SABAYON HURRICANE CAT JOHN F KENNEDY GALAN DE CINE POTRILLOS POTRANCAS NOTAS CÓMO LLEGAR ÍNDICE POTRILLOS POTRILLOS 1 ES CALIU Easing Along - Entidad Suprema por Rock Hard Ten 2 EL IMPENETRABLE Violence - La Imparcial por Easing Along 3 VITARO Violence - Vlytava por Southern Halo 4 PADRICIANO Violence - Petrova por Southern Halo 5 BOLLANI Manipulator - Be My Baby por Exchange Rate 6 LEONCINO Manipulator - Latoscana por Sea The Stars 7 ONDEADOR Manipulator - Onda Chic por Easing Along 8 ARDE DENTRO Manipulator - Arde La Ciudad por Stormy Atlantic 9 LINCE IBERICO Manipulator - Linkwoman por Southern Halo 10 FANATICO MISTICO Manipulator - Fancy Kitty por Easing Along 11 MUY SARDINERO Manipulator - Monaguesca por Easing Along 12 DON BERTONI Manipulator - Dayli por Mutakddim 13 ANANA FIZZ Manipulator - Anantara por Exchange Rate 14 MUÑECO VUDU Manipulator - Muñeca Lista por Lizard Island 15 CARROBBIO Lizard Island - Cookie Crisp por Mutakddim 16 SAN DOMENICO Lizard Island - Saratogian por Candy Ride 17 ENTRE VOS Y YO Sixties Icon - Entretiempo por Exchange Rate 18 SAGARDOY Sixties Icon - Sagardoa por Easing Along 19 CILINDRO Sixties Icon - Cilindrada por Touch Gold 20 DON BASSI Sixties Icon - Devotion Unbridled por Unbridled 21 ILUMINISMO Sixties Icon - Ilegalidad por Easing Along 22 BUEN BELGA Zensational - Buenas Costumbres por Honour And Glory 23 LEON AMERICANO Zensational - Leandrinha por Bernstein -

Mother Most Amiable

VOLUME 40 De Maria Nunquam Satis ISSUE N O. 52 a To Promote Faithful Obedience to the Legitimate Teaching Magisterium of the One, TrueTrue,, Holy, CatholicCatholic,, Apostolic Church Founded by Jesus Christ... a To Preserve Without Compromise or DiluDilutiontion the TraditionsTraditions,Traditions , Dogma and Doctrines of the One, True Church... a To Work and Pray for the Triumph of the Immaculate Heart of Mary Our Queen and the Resultant Reign of Christ Our King... Motherhere shall always Most be thatAmiable enmity mentioned in Scripture T betweenIn the lastthe four Christian titles weforces have of considered the Our Mother’s holinessWoman by(Mary) looking and at whatthe sheAnti-Christ was not , that is, negatively. Nowforces let usof studythe serpent what she (Lucifer). is . And whileThe veryin our first presentthing that day we arethose told about her is that she is most amiable, i.e. , most lovable. The word forces of Anti-Christ (Freemasonry, “amiable,” as we commonly use it, has not in English the sameCommunism, force as theAtheistic Latin word Materialism, “amabilis,” which means, as weLiberalism have said, “lovable.”and its Protestant offspring,But is there Apostate not something Modernism, within us which tells us this withoutSocialism, its being Militant put intoIslam, words? etc.) Doare not her statues and pictures,gaining if theyuniversal are at allvictories in good taste,in depict Mary as a sweet, gentle, modest virgin? In a word is not her establishing the reign of the outstanding characteristic this—that she is one whom you Luciferian brotherhood throughout feel you must love? theShe world, is one we you who would fight neverbeneath be theafraid to go to, for you knowstandard she would of the never Cross be cross, know sharp, that sneering, unkind, or boredultimately and unwillingMary, Mother to listen of God to andyou. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

United in Victory Toledo-Winlock Soccer Team Survives Dameon Pesanti / [email protected] Opponents of Oil Trains Show Support for a Speaker Tuesday

It Must Be Tigers Bounce Back Spring; The Centralia Holds Off W.F. West 9-6 in Rivalry Finale / Sports Weeds are Here / Life $1 Midweek Edition Thursday, May 1, 2014 Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com United in Victory Toledo-Winlock Soccer Team Survives Dameon Pesanti / [email protected] Opponents of oil trains show support for a speaker Tuesday. Oil Train Opponents Dominate Centralia Meeting ONE-SIDED: Residents Fear Derailments, Explosions, Traffic Delays By Dameon Pesanti [email protected] More than 150 people came to Pete Caster / [email protected] the Centralia High School audito- Toledo-Winlock United goalkeeper Elias delCampo celebrates after leaving the Winlock School District meeting where the school board voted to strike down the rium Tuesday night to voice their motion to dissolve the combination soccer team on Wednesday evening. concerns against two new oil transfer centers slated to be built in Grays Harbor. CELEBRATION: Winlock School Board The meeting was meant to be Votes 3-2 to Keep Toledo/Winlock a platform for public comments and concerns related to the two Combined Boys Soccer Program projects, but the message from attendees was clear and unified By Christopher Brewer — study as many impacts as pos- [email protected] sible, but don’t let the trains come WINLOCK — United they have played for nearly through Western Washington. two decades, and United they will remain for the Nearly every speaker ex- foreseeable future. pressed concerns about the Toledo and Winlock’s combined boys’ soccer increase in global warming, program has survived the chopping block, as the potential derailments, the unpre- Winlock School Board voted 3-2 against dissolving paredness of municipalities in the the team at a special board meeting Wednesday eve- face of explosions and the poten- ning.