A Comprehensive Guide to Trumpet Orchestral Excerpts: an Analysis of Excerpts by Bartók, Beethoven, Mahler, and Mussorgsky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeing (For) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2014 Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Benjamin Park, "Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623644. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-t267-zy28 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park Anderson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, College of William and Mary, 2005 Bachelor of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program College of William and Mary May 2014 APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Benjamin Park Anderson Approved by T7 Associate Professor ur Knight, American Studies Program The College -

A Selection of Contemporary Fanfares for Multiple Trumpets Demonstrating Evolutionary Processes in the Fanfare Form

MODERN FORMS OF AN ANCIENT ART: A SELECTION OF CONTEMPORARY FANFARES FOR MULTIPLE TRUMPETS DEMONSTRATING EVOLUTIONARY PROCESSES IN THE FANFARE FORM Paul J. Florek, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2015 APPROVED: Keith Johnson, Major Professor Eugene Corporon, Committee Member John Holt, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Costas Tsatsoulis, Interim Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Florek, Paul J. Modern Forms of an Ancient Art: A Selection of Contemporary Fanfares for Multiple Trumpets Demonstrating Evolutionary Processes in the Fanfare Form. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2015, 73 pp., 1 table, 26 figures, references, 96 titles. The pieces discussed throughout this dissertation provide evidence of the evolution of the fanfare and the ability of the fanfare, as a form, to accept modern compositional techniques. While Britten’s Fanfare for St. Edmundsbury maintains the harmonic series, it does so by choice rather than by the necessity in earlier music played by the baroque trumpet. Stravinsky’s Fanfare from Agon applies set theory, modal harmonies, and open chords to blend modern techniques with medieval sounds. Satie’s Sonnerie makes use of counterpoint and a rather unusual, new characteristic for fanfares, soft dynamics. Ginastera’s Fanfare for Four Trumpets in C utilizes atonality and jazz harmonies while Stravinsky’s Fanfare for a New Theatre strictly coheres to twelve-tone serialism. McTee’s Fanfare for Trumpets applies half-step dissonance and ostinato patterns while Tower’s Fanfare for the Uncommon Woman demonstrates a multi-section work with chromaticism and tritones. -

Kidsbook © Is a Publication of the Negaunee Music Institute

KIDS�OOK CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA CSO SCHOOL CONCERTS May 4, 2018, 10:15 and 12:00 CSO FAMILY MATINEE SERIES May 5, 2018, 11:00 and 12:45 TheThe FirebirdFirebird 312-294-3000 | CSO.ORG | 220 S. MICHIGAN AVE. | CHICAGO THE FIREBIRD PERFORMERS Members of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Tania Miller conductor Joffrey Academy Trainees and Studio Company guest dancers WHAT WOULD IT �E LIKE TO LIVE PROGRAM INCLUDES SELECTIONS FROM IN A WORLD WITHOUT HARMONY? Glière Russian Sailors’ Dance This program explores the ways from The Red Poppy that dynamic orchestral music and Prokofiev exquisite ballet dancing convey Suite No. 2 from emotion and tell stories of conflict Romeo and Juliet, and harmony. Our concert features Op. 64B Stravinsky’s Suite from The Firebird Tchaikovsky which depicts the heroic efforts of Swan Lake, Op. 20 Prince Ivan and a magical glowing Stravinsky bird struggling to defeat evil and Suite from The Firebird (1919) restore peace to the world. 2 CSO School Concerts / CSO Family Matinee series / THE FIREBIRD CONFLICT &HARMONY Each piece on our program communicates a unique combination of conflict and harmony. The first piece on the concert is Russian Sailor’s Dance from the ballet The Red Poppy by Reinhold Glière [say, Glee-AIR]. What kind of emotion do you feel as the low strings and brass begin the piece? William Shakespeare’s What emotion do you feel as the story of Romeo and Juliet is music gets faster? Would you say filled with conflict, and composer this piece is mostly about harmony Sergei Prokofiev [say: pro-CO-fee- or conflict? Why? What story of ] brilliantly captures this emotion do you imagine the music is in his ballet based on this timeless telling you? tale. -

Mouthpiece Vol. 22 Issue 4

DecemberThe Journal2020 of the Australian Mouthpiece Trumpet Guild Pty Ltd ABN Volume76 085 24022 Issue 446 4 Mouthpiece gets a new look in 2021 Page 17 Interview with “Mr. Clean” — James Wilt of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Page 15 ITG News Page 8 ...and more! Next issue Orchestra matters, (Aussie trumpets of the Aukland Phil); Cornet Coirner International corner, December 2020 1 Volume 22 Issue 4 December 2020 Mouthpiece Volume 22 Issue 4 CONTENTS Click the page number to go to the page Publishing information Page 2 Guild Notes, Editorial, Page 3 Australian Trumpet News Page 4 A Blast from the past Page 7 ITG News Page 8 Orchestra matters (held over to 2021) Page 10 New work review Page 12 Cornet Corner Page 13 International Corner Page 15 Mouthpiece gets a new cover! Page 19 Snippets Page 20 PUBLISHING INFORMATION ADVERTISING RATES Deadlines for 2020 publications: 1 issue 4 issues Issue 1 February 15 (March issue) Issue 2 May 15 (June issue) Full page $100 $340 Issue 3 August 15 (September issue) 1/2 page $55 $180 Issue 4 November 15 (December issue) PLEASE NOTE: The above dates are firm. We need copy 1/4 Page $30 $100 within these time frames for efficient production of 1/8 page) $15 $55 Mouthpiece. Provide copy of adverts and articles via email . JPEG versions Classifieds(4 lines max.) $5 $15 preferred. Enquiries to: Australian Trumpet Guild Pty Ltd P.O. Box 1073 Wahroonga Sponsorships are also available. Contact the ATG NSW 2076 Ph: (02) 9489-6940 for details of packages including advertising, email: [email protected] conference stands and other benefits. -

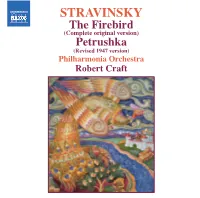

STRAVINSKY the Firebird

557500 bk Firebird US 14/01/2005 12:19pm Page 8 Philharmonia Orchestra STRAVINSKY The Philharmonia Orchestra, continuing under the renowned German maestro Christoph von Dohnanyi as Principal Conductor, has consolidated its central position in British musical life, not only in London, where it is Resident Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall, but also through regional residencies in Bedford, Leicester and Basingstoke, The Firebird and more recently Bristol. In recent seasons the orchestra has not only won several major awards but also received (Complete original version) unanimous critical acclaim for its innovative programming policy and commitment to new music. Established in 1945 primarily for recordings, the Philharmonia Orchestra went on to attract some of this century’s greatest conductors, such as Furtwängler, Richard Strauss, Toscanini, Cantelli and von Karajan. Otto Klemperer was the Petrushka first of many outstanding Principal Conductors throughout the orchestra’s history, including Maazel, Muti, (Revised 1947 version) Sinopoli, Giulini, Davis, Ashkenazy and Salonen. As the world’s most recorded symphony orchestra with well over a thousand releases to its credit, the Philharmonia Orchestra also plays a prominent rôle as one of the United Kingdom’s most energetic musical ambassadors, touring extensively in addition to prestigious residencies in Paris, Philharmonia Orchestra Athens and New York. The Philharmonia Orchestra’s unparalleled international reputation continues to attract the cream of Europe’s talented young players to its ranks. This, combined with its brilliant roster of conductors and Robert Craft soloists, and the unique warmth of sound and vitality it brings to a vast range of repertoire, ensures performances of outstanding calibre greeted by the highest critical praise. -

A Comparison of Rhythm, Articulation, and Harmony in Jean-Michel Defaye's À La Manière De Stravinsky Pour Trombone Et Piano

A COMPARISON OF RHYTHM, ARTICULATION, AND HARMONY IN JEAN- MICHEL DEFAYE’S À LA MANIÈRE DE STRAVINSKY POUR TROMBONE ET PIANO TO COM MON COMPOSITIONAL STRATEGIES OF IGOR STRAVINSKY Dustin Kyle Mullins, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2014 APPROVED: Tony Baker, Major Professor Eugene Corporon, Minor Professor John Holt, Committee Member and Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the College of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Mullins, Dustin Kyle. A Comparison of Rhythm, Articulation, and Harmony in Jean-Michel Defaye’s À la Manière de Stravinsky pour Trombone et Piano to Common Compositional Strategies of Igor Stravinsky. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2014, 45 pp., 2 tables, 27 examples, references, 28 titles. À la Manière de Stravinsky is one piece in a series of works composed by Jean- Michel Defaye that written emulating the compositional styles of significant composers of the past. This dissertation compares Defaye’s work to common compositional practices of Igor Stravinsky (1882 – 1971). There is currently limited study of Defaye’s set of À la Manière pieces and their imitative characteristics. The first section of this dissertation presents the significance of the project, current literature, and methods of examination. The next section provides critical information on Jean-Michel Defaye and Igor Stravinsky. The following three chapters contain a compositional comparison of À la Manière de Stravinsky to Stravinsky’s use of rhythm, articulation, and harmony. The final section draws a conclusion of the piece’s significance in the solo trombone repertoire. -

The History and Usage of the Tuba in Russia

The History and Usage of the Tuba in Russia D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By James Matthew Green, B.A., M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2015 Document Committee: Professor James Akins, Advisor Professor Joseph Duchi Dr. Margarita Mazo Professor Bruce Henniss ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Copyright by James Matthew Green 2015 ! ! ! ! ! ! Abstract Beginning with Mikhail Glinka, the tuba has played an important role in Russian music. The generous use of tuba by Russian composers, the pedagogical works of Blazhevich, and the solo works by Lebedev have familiarized tubists with the instrument’s significance in Russia. However, the lack of available information due to restrictions imposed by the Soviet Union has made research on the tuba’s history in Russia limited. The availability of new documents has made it possible to trace the history of the tuba in Russia. The works of several composers and their use of the tuba are examined, along with important pedagogical materials written by Russian teachers. ii Dedicated to my wife, Jillian Green iii Acknowledgments There are many people whose help and expertise was invaluable to the completion of this document. I would like to thank my advisor, professor Jim Akins for helping me grow as a musician, teacher, and person. I would like to thank my committee, professors Joe Duchi, Bruce Henniss, and Dr. Margarita Mazo for their encouragement, advice, and flexibility that helped me immensely during this degree. I am indebted to my wife, Jillian Green, for her persistence for me to finish this document and degree. -

Concert Band Joan Dealbuquerque, Conductor

Concert Band Joan deAlbuquerque, conductor 2019 Southwest Tour Tour Program To be selected from the following: Rocky Point Holiday Ron Nelson (b. 1929) Be Thou My Vision David Gillingham (b. 1947) Paris Sketches Martin Ellerby (b. 1957) I. Saint-Germain-de-Prés II. Pigalle JOAN DEALBUQUERQUE, III. Père Lachaise CONDUCTOR IV. Les Halles Joan deAlbuquerque was appointed director of bands at Luther College in 2011. She conducts the Luther College Concert Band and the Wind and Percussion Ensemble. Konzertstück for Four Horns and Band Prior to joining Luther College, deAlbuquerque served as the associate director of bands at California State Robert Schumann (1810–1856) University, Long Beach, and as interim director of bands Arr. Leonard Smith at Adams State College in Alamosa, Colorado. An NOTE: Concert Band is performing the first of the three movements. experienced public school teacher, she was director of bands at Pinckney High School in Michigan, where she conducted the wind symphony and marching band in addition to teaching instrumental and general music at the INTERMISSION elementary and middle school levels. Professor deAlbuquerque earned a doctor of music arts degree in wind conducting from the University of North Scherzo: Cat and Mouse Texas as a student of Eugene Migliaro Corporon. She holds Robert Spittal (b. 1963) a master of music degree in wind conducting from Michigan State University, where she studied with John Whitwell. A graduate of Macomb Community College, deAlbuqerque earned a bachelor of music education degree from La Procession du Rocio Michigan State University. Joaquin Turina (1882–1949) As a guest conductor, clinician, and adjudicator, Trans. -

Arbiter, September 26 Associated Students of Boise State University

Boise State University ScholarWorks Student Newspapers (UP 4.15) University Documents 9-26-1977 Arbiter, September 26 Associated Students of Boise State University Although this file was scanned from the highest-quality microfilm held by Boise State University, it reveals the limitations of the source microfilm. It is possible to perform a text search of much of this material; however, there are sections where the source microfilm was too faint or unreadable to allow for text scanning. For assistance with this collection of student newspapers, please contact Special Collections and Archives at [email protected]. Alcohol, the pard, ndthelow continued from cover transcript of the hearing, I think have never really been answer- feel there is ,a very good chance these important questions ans- you will find that it is quite clear ed. TIley haven't even been that we will.be ,bac,tc in court in wered thus solving the "alcohol consumption of alcohol on the that there was not even a valid addressed. For this reason., I the near future attempted to get problem 10 once and for all. state's campuses pursuant to attempt made by the defendant the emergency clause of the state board to prove that there Administrative Procedure Act. existed imminent- peril to the This clause allows a state board public. What the board did do ·c or agency to circumvent the was to point out that they were regularrule of making proced- making a good faith effort to Stitzel new Business dean ure i.e. giving' notice, holding follow the APA. Which in fact hearings, etc., if the board or they are. -

Theory of Music-Stravinsky

Theory of Music – Jonathan Dimond Stravinsky (version October 2009) Introduction Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) was one of the most internationally- acclaimed composer conductors of the 20th Century. Like Bartok, his compositional style drew from the country of his heritage – Russia, in his case. Both composers went on to spend time in the USA later in their careers also, mostly due to the advent of WWII. Both composers were also exposed to folk melodies early in their lives, and in the case of Stravinsky, his father sang in Operas. Stravinsky’s work influenced Bartok’s – as it tended to influence so many composers working in the genre of ballet. In fact, Stravinsky’s influence was so broad that Time Magazine named him one of th the most influential people of the 20 Century! http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Igor_Stravinsky More interesting, however, is the correlation of Stravinsky’s life with that of Schoenberg, who were contemporaries of each other, yet had sometimes similar and sometimes contradictory approaches to music. The study of their musical output is illuminated by their personal lives and philosophies, about which much has been written. For such writings on Stravinsky, we have volumes of work created by his long-term companion and assistant, the conductor/musicologist Robert Craft. {See the Bibliography.} Periods Stravinsky’s compositions fall into three distinct periods. Some representative works are listed here also: The Dramatic Russian Period (1906-1917) The Firebird (1910, revised 1919 and 1945) Petrouchka (1911, revised 1947)) -

January 15Th 1986

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Coyote Chronicle (1984-) Arthur E. Nelson University Archives 1-15-1986 January 15th 1986 CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/coyote-chronicle Recommended Citation CSUSB, "January 15th 1986" (1986). Coyote Chronicle (1984-). 190. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/coyote-chronicle/190 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Arthur E. Nelson University Archives at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Coyote Chronicle (1984-) by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. J» '• .«S •*:"'* %t:RV1NG THE CAL SfATfe: UNtVERSlTY, SAN BERNARDINO COMMUNITY:^ M Jumary 1549M Vohmie 20 9 DR. HALPERN CHOSEN AS OUTSTANDING PROFESSOR OF 1985 by Jackie WUson Students constantly praise Dr. She's funny, informative, Halpera's enthusiasm in her likeable and an authority in her teaching. They say she has a field of critica] thinking. She is an terrific ability to make complex associate professor of psychology sutgects simpler as well as and also the assodate dean of enjoyaUe. Her reception to undergraduate programs here at studrat problems and helping CSUSB. She's a published author them to resolve them is another and has served on a variety of plus. One student said ''She campus committees, most recently exemplifies all the best qualities in chai^ the campus' Innovative the skin of teaching." **1 try to Ideas Committee. Who is this involve my students as much as woman extraordinare? Dr. Diane possiUe", Dr. Haipem said what F. Haipem of course!! she is bcT ^udents. -

2020Teacher Packet

Jacob Joyce, Conductor 2020 Teacher Packet This is designed for teachers attending the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra’s Community Health Network Discovery Concerts. Questions or comments may be directed to the ISO Learning Community. Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra | 32 E. Washington St., Suite 600 | Indianapolis, IN 46204 Table of Contents Musical Selections STRAVINSKY 4-6 “The Augurs of Spring (Dance of the Young Girls)” from Le Sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring) 7-9 WILLIAMS Main Title from Jurassic Park STRAUSS 10-11 “Something Waltz” from Der Rosenkavalier, Op. 59 STRAVINSKY 12-13 “Infernal Dance of All Kastchei’s Subjects” from L’Oiseau de feu (The Firebird) BACH (orch. STOKOWSKI) 14-15 “Passacaglia” from Passacaglia and Fugue in C Minor, BWV 582 CLYNE 16-17 “Space” from Rift SILVESTRI Main Theme from Back to the Future 18-19 Other Activities 20 Sources 21 Standards Covered 22-24 Don’t forget – You can deepen your connection to this curriculum by participating in the Symphony in Color program as well! It’s free! For more information visit www.indianapolissymphony.org/education/teachers/symphony-in-color Be sure to check out the brand new Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra Instrument Family Videos on our website! www.indianapolissymphony.org/education/teachers/young-peoples-discovery-concerts Standards used throughout the curriculum are listed at the end of the packet as well as next to individual questions. 2 INDIANAPOLIS SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Jacob Joyce, Conductor Jacob Joyce is a conductor from Ann Arbor, MI. Recently appointed as the Associate Conductor of the Indianapolis Symphony, Jacob is quickly gaining recognition as an innovative and dynamic presence on the podium.