Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

His Honour Judge Peter Smithwick for the Tribunal

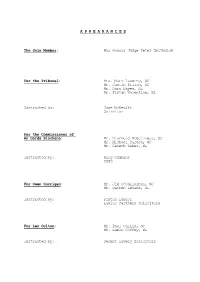

A P P E A R A N C E S The Sole Member: His Honour Judge Peter Smithwick For the Tribunal: Mrs. Mary Laverty, SC Mr. Justin Dillon, SC Mr. Dara Hayes, BL Mr. Fintan Valentine, BL Instructed by: Jane McKevitt Solicitor For the Commissioner of An Garda Siochana: Mr. Diarmuid McGuinness, SC Mr. Michael Durack, SC Mr. Gareth Baker, BL Instructed by: Mary Cummins CSSO For Owen Corrigan: Mr. Jim O'Callaghan, SC Mr. Darren Lehane, BL Instructed by: Fintan Lawlor Lawlor Partners Solicitors For Leo Colton: Mr. Paul Callan, SC Mr. Eamon Coffey, BL Instructed by: Dermot Lavery Solicitors For Finbarr Hickey: Fionnuala O'Sullivan, BL Instructed by: James MacGuill & Co. For the Attorney General: Ms. Nuala Butler, SC Mr. Douglas Clarke, SC Instructed by: CSSO For Freddie Scappaticci: Eavanna Fitzgerald, BL Pauline O'Hare Instructed by: Michael Flanigan Solicitor For Kevin Fulton: Mr. Neil Rafferty, QC Instructed by: John McAtamney Solicitor For Breen Family: Mr. John McBurney For Buchanan Family/ Heather Currie: Ernie Waterworth McCartan Turkington Breen Solicitors For the PSNI: Mark Robinson, BL NOTICE: A WORD INDEX IS PROVIDED AT THE BACK OF THIS TRANSCRIPT. THIS IS A USEFUL INDEXING SYSTEM, WHICH ALLOWS YOU TO QUICKLY SEE THE WORDS USED IN THE TRANSCRIPT, WHERE THEY OCCUR AND HOW OFTEN. EXAMPLE: - DOYLE [2] 30:28 45:17 THE WORD “DOYLE” OCCURS TWICE PAGE 30, LINE 28 PAGE 45, LINE 17 I N D E X Witness Page No. Line No. OWEN CORRIGAN CROSS-EXAMINED BY MR. O'CALLAGHAN 4 1 Smithwick Tribunal - 1 August 2012 - Day 119 1 1 THE TRIBUNAL RESUMED ON THE 1ST AUGUST 2012 AS FOLLOWS: 2 3 MR. -

Double Blind

Double Blind The untold story of how British intelligence infiltrated and undermined the IRA Matthew Teague, The Atlantic, April 2006 Issue https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2006/04/double-blind/304710/ I first met the man now called Kevin Fulton in London, on Platform 13 at Victoria Station. We almost missed each other in the crowd; he didn’t look at all like a terrorist. He stood with his feet together, a short and round man with a kind face, fair hair, and blue eyes. He might have been an Irish grammar-school teacher, not an IRA bomber or a British spy in hiding. Both of which he was. Fulton had agreed to meet only after an exchange of messages through an intermediary. Now, as we talked on the platform, he paced back and forth, scanning the faces of passersby. He checked the time, then checked it again. He spoke in an almost impenetrable brogue, and each time I leaned in to understand him, he leaned back, suspicious. He fidgeted with several mobile phones, one devoted to each of his lives. “I’m just cautious,” he said. He lives in London now, but his wife remains in Northern Ireland. He rarely goes out, for fear of bumping into the wrong person, and so leads a life of utter isolation, a forty-five-year-old man with a lot on his mind. During the next few months, Fulton and I met several times on Platform 13. Over time his jitters settled, his speech loosened, and his past tumbled out: his rise and fall in the Irish Republican Army, his deeds and misdeeds, his loyalties and betrayals. -

Voices from the Grave Ed Moloney Was Born in England. a Former Northern Ireland Editor of the Irish Times and Sunday Tribune, He

Voices prelims:Layout 1 3/12/09 11:52 Page i Voices from the Grave Ed Moloney was born in England. A former Northern Ireland editor of the Irish Times and Sunday Tribune, he was named Irish Journalist of the Year in 1999. Apart from A Secret History of the IRA, he has written a biography of Ian Paisley. He now lives and works in New York. Professor Thomas E. Hachey and Dr Robert K. O’Neill are the General Editors of the Boston College Center for Irish Programs IRA/UVF project, of which Voices from the Grave is the inaugural publication. Voices prelims:Layout 1 3/12/09 11:52 Page ii by the same author the secret history of the ira paisley: from demagogue to democrat? Voices prelims:Layout 1 3/12/09 11:52 Page iii ed moloney VOICES FROM THE GRAVE Two Men’s War in Ireland The publishers would like to acknowledge that any interview material used in Voices from the Grave has been provided by kind permission from the Boston College Center for Irish Programs IRA/UVF project that is archived at the Burns Library on the Chestnut Hill campus of Boston College. Voices prelims:Layout 1 3/12/09 11:52 Page iv First published in 2010 by Faber and Faber Limited Bloomsbury House 74–77 Great Russell Street London wc1b 3da Typeset by Faber and Faber Limited Printed in England by CPI Mackays, Chatham All rights reserved © Ed Moloney, 2010 Interview material © Trustees of Boston College, 2010 The right of Ed Moloney to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 Use of interview material by kind permission of The Boston College Irish Center’s Oral History Archive. -

A Process of Analysis

A process of analysis (1) The Protestant/Unionist/Loyalist community Compiled by Michael Hall ISLAND 107 PAMPHLETS 1 Published February 2015 by Island Publications / Farset Community Think Tanks Project 466 Springfield Road, Belfast BT12 7DW © Michael Hall 2015 [email protected] http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/islandpublications cover photographs © Michael Hall The Project wishes to thank all those who participated in the discussions and interviews from which this publication was compiled. This first part of a three-part project has received financial support from The Reconciliation Fund Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Dublin. Printed by Regency Press, Belfast The Island Pamphlets series was launched in 1993 to stimulate a community-wide debate on historical, cultural, political and socio-economic issues. Most of the pamphlets are edited accounts of discussions undertaken by small groups of individuals – the ‘Community Think Tanks’ – which have embraced (on both a ‘single identity’ and a cross-community basis) Loyalists, Republicans, community activists, women’s groups, victims, cross-border workers, ex-prisoners, young people, senior citizens and others. To date 106 titles have been produced and 190,400 pamphlets have been distributed at a grassroots level. Many of the titles are available for (free) download from http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/islandpublications. 2 Introduction Sixteen years after the signing of the Good Friday Agreement issues surrounding identity, marching and flags in Northern Ireland remain as contentious as ever. These unresolved matters have poisoned political discourse and at times threatened to destabilise the political institutions. Even the Stormont House Agreement (announced in the final days of 2014) in which Northern Ireland’s political parties reached a belated consensus on a range of financial and legacy matters, once again pushed any discussion of identity-related issues further into the future. -

His Honour Judge Peter Smithwick for the Tribunal

A P P E A R A N C E S The Sole Member: His Honour Judge Peter Smithwick For the Tribunal: Mrs. Mary Laverty, SC Mr. Justin Dillon, SC Mr. Dara Hayes, BL Mr. Fintan Valentine, BL Instructed by: Jane McKevitt Solicitor For the Commissioner of An Garda Siochana: Mr. Diarmuid McGuinness, SC Mr. Michael Durack, SC Mr. Gareth Baker, BL Instructed by: Mary Cummins CSSO For Owen Corrigan: Mr. Jim O'Callaghan, SC Mr. Darren Lehane, BL Instructed by: Fintan Lawlor Lawlor Partners Solicitors For Leo Colton: Mr. Paul Callan, SC Mr. Eamon Coffey, BL Instructed by: Dermot Lavery Solicitors For Finbarr Hickey: Fionnuala O'Sullivan, BL Instructed by: James MacGuill & Co. For the Attorney General: Ms. Nuala Butler, SC Mr. Douglas Clarke, SC Instructed by: CSSO For Freddie Scappaticci: Eavanna Fitzgerald, BL Pauline O'Hare Instructed by: Michael Flanigan Solicitor For Kevin Fulton: Mr. Neil Rafferty, QC Instructed by: John McAtamney Solicitor For Breen Family: Mr. John McBurney For Buchanan Family/ Heather Currie: Ernie Waterworth McCartan Turkington Breen Solicitors For the PSNI: Mark Robinson, BL NOTICE: A WORD INDEX IS PROVIDED AT THE BACK OF THIS TRANSCRIPT. THIS IS A USEFUL INDEXING SYSTEM, WHICH ALLOWS YOU TO QUICKLY SEE THE WORDS USED IN THE TRANSCRIPT, WHERE THEY OCCUR AND HOW OFTEN. EXAMPLE: - DOYLE [2] 30:28 45:17 THE WORD “DOYLE” OCCURS TWICE PAGE 30, LINE 28 PAGE 45, LINE 17 I N D E X Witness Page No. Line No. WILLIAM FRAZER EXAMINED BY MRS. LAVERTY 19 1 CROSS-EXAMINED BY MR. LEHANE 37 16 CROSS-EXAMINED BY MR. -

British Irish

British Irish RIGHTS WATCH THE MURDER OF JOHN DIGNAM, 1ST JULY 1992 DECEMBER 2005 0 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 British Irish RIGHTS WATCH (BIRW) is an independent non-governmental organisation that has been monitoring the human rights dimension of the conflict and the peace process in Northern Ireland since 1990. Our services are available, free of charge, to anyone whose human rights have been violated because of the conflict, regardless of religious, political or community affiliations. We take no position on the eventual constitutional outcome of the conflict. 1.2 This report concerns the murder of John Dignam, whose body was found on 1st July 1992. The bodies of two other men, Aidan Starrs and Gregory Burns, were found on the same day at separate locations. The IRA were responsible for all three murders. They claimed that the men were informers and that they had been involved in the murder of a woman called Margaret Perry, who was killed a year earlier. According to a confession extorted from John Dignam, he was an accessory after the fact, in that he helped Aidan Starrs to hide her body. It would appear that Gregory Burns gave the orders for her murder and that Aidan Starrs planned it. 1.3 In this report, we set out what is known about John Dignam’s death. While many of the facts are known, some significant questions remain unanswered. No-one has been charged with John Dignam’s murder, nor those of Aidan Starrs or Gregory Burns. The only evidence that John Dignam was an informer is his own confession, extorted from him by the IRA under extreme pressure and probably under the threat of torture. -

A P P E a R a N C E S the Sole Member: His Honour Judge Peter Smithwick for the Tribunal: Mrs. Mary Laverty, SC Mr. Justin Dill

A P P E A R A N C E S The Sole Member: His Honour Judge Peter Smithwick For the Tribunal: Mrs. Mary Laverty, SC Mr. Justin Dillon, SC Mr. Dara Hayes, BL Mr. Fintan Valentine, BL Instructed by: Jane McKevitt Solicitor For the Commissioner of An Garda Siochana: Mr. Diarmuid McGuinness, SC Mr. Michael Durack, SC Mr. Gareth Baker, BL Instructed by: Mary Cummins CSSO For Owen Corrigan: Mr. Jim O'Callaghan, SC Mr. Darren Lehane, BL Instructed by: Fintan Lawlor Lawlor Partners Solicitors For Leo Colton: Mr. Paul Callan, SC Mr. Eamon Coffey, BL Instructed by: Dermot Lavery Solicitors For Finbarr Hickey: Fionnuala O'Sullivan, BL Instructed by: James MacGuill & Co. For the Attorney General: Ms. Nuala Butler, SC Mr. Douglas Clarke, SC Instructed by: CSSO For Freddie Scappaticci: Eavanna Fitzgerald, BL Pauline O'Hare Instructed by: Michael Flanigan Solicitor For Kevin Fulton: Mr. Neil Rafferty, QC Instructed by: John McAtamney Solicitor For Breen Family: Mr. John McBurney For Buchanan Family/ Heather Currie: Ernie Waterworth McCartan Turkington Breen Solicitors For the PSNI: Mark Robinson, BL NOTICE: A WORD INDEX IS PROVIDED AT THE BACK OF THIS TRANSCRIPT. THIS IS A USEFUL INDEXING SYSTEM, WHICH ALLOWS YOU TO QUICKLY SEE THE WORDS USED IN THE TRANSCRIPT, WHERE THEY OCCUR AND HOW OFTEN. EXAMPLE: - DOYLE [2] 30:28 45:17 THE WORD “DOYLE” OCCURS TWICE PAGE 30, LINE 28 PAGE 45, LINE 17 I N D E X Witness Page No. Line No. DAVID McCONVILLE EXAMINED BY MR. DILLON 3 1 CROSS-EXAMINED BY MR. DURACK 64 2 Smithwick Tribunal - 15 May 2012 - Day 99 1 1 THE TRIBUNAL RESUMED ON THE 15TH OF MAY, 2012, AS FOLLOWS: 2 3 CHAIRMAN: Good morning. -

The Leadership of the Republican Movement During the Peace Process

Appendix I: The Leadership of the Republican Movement during the Peace Process Other leading members of Sinn Féin Conor Murphy (p) Mary-Lou McDonald Alex Maskey (p) Caoimhghín Ó Caoláin Core strategy personnel Behind-the-scenes IRA figures Arthur Morgan (p) Sean Crowe (p) Gerry Adams (p) Michelle Gildernew Martin McGuinness (p) Aengus O Snodaigh Ted Howell (p) Bairbre de Brun Pat Doherty Martin Ferris (p) Gerry Kelly (p) Mitchel McLaughlin Influential ex-prisoners Declan Kearney (p) Behind-the-scenes Sinn Féin Tom Hartley (p) figures Seanna Walsh (p) Jim Gibney (p) Aidan McAteer (p) Padraig Wilson (p) Brian Keenan (p) Richard McAuley (p) Leo Green (p) Chrissie McAuley Bernard Fox (p) (until 2006) Siobhan O’Hanlon Brendan McFarlane (p) Dawn Doyle Raymond McCartney (p) Rita O’Hare Laurence McKeown (p) Denis Donaldson (until 2005) (p) Ella O’Dwyer (p) Lucilita Breathnach Martina Anderson (p) Dodie McGuinness (p) denotes former republican prisoner 193 Appendix II: The Geographical Base of the Republican Leadership Gerry Adams Ted Howell Gerry Kelly Declan Kearney Tom Hartley Jim Gibney Seanna Walsh Padraig Wilson Leo Green Bernard Fox Mary-Lou McDonald Pat Doherty (Donegal) Brendan McFarlane Martin McGuinness Sean Crowe Martin Ferris (Kerry) Laurence McKeown Mitchel McLaughlin Aengus O Snodaigh Conor Murphy (South Armagh) Alex Maskey Raymond McCartney Dawn Doyle Arthur Morgan (Louth) Denis Donaldson Martina Anderson Lucilita Breathnach Caoimhghín Ó Caoláin (Monaghan) Chrissie McAuley Dodie McGuinness Rita O’Hare Michelle Gildernew (Fermanagh) Richard McAuley Ella O’Dwyer Aidan McAteer Siobhan O’Hanlon Brian Keenan BELFAST DERRY DUBLIN OTHER 194 Notes Introduction 1. Sinn Féin Northern Ireland Assembly Election Leaflet, Vote Sinn Féin, Vote Nation- alist: Vote Carron and Molloy 1 and 2 (1982) (Linenhall Library Political Collection – henceforth LLPC). -

Northern Ireland Peace Monitoring Report, Number Four

Community Relations Council Northern Ireland Peace Monitoring Report Number Four September 2016 Robin Wilson Peace Monitoring Report The Northern Ireland Peace Monitoring Report Number Four Robin Wilson September 2016 3 Peace Monitoring Report Sources and acknowledgements This report draws mainly on statistics which are in the public domain. Datasets from various government departments and public bodies in Northern Ireland have been used and comparisons made with figures produced by similar organisations in England, Scotland, Wales and the Republic of Ireland. Using this variety of sources means there is no standard model that applies across the different departments and jurisdictions. Many organisations have also changed the way in which they collect their data over the years, which means that in some cases it has not been possible to provide historical perspective on a consistent basis. For some indicators, only survey-based data are available. When interpreting statistics from survey data, such as the Labour Force Survey, it is worth bearing in mind that they are estimates associated with confidence intervals (ranges in which the true value is likely, to a certain probability, to lie). In other cases where official figures may not present the full picture, such as crimes recorded by the police, survey data are included because they may provide a more accurate estimate. Data, however, never speak ‘simply for themselves’. And political debate in Northern Ireland takes a very particular, largely self-contained form. To address this and provide perspective, previous reports have included comparative international data where available and appropriate. This report builds on its predecessors by painting further international context: expert and comparative literature is added where relevant as are any benchmarks established by standard-setting bodies. -

Submission to UN Special Rapporteur Pablo De Greiff 2015

RELATIVES FOR JUSTICE Submission to Special Rapporteur on Truth, Justice, Reparation and Guarantees of Non-Recurrence, Pablo De Greiff November 2015 Relatives for Justice welcomes this opportunity to engage with the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Truth, Justice, Reparation and Guarantees of Non-Recurrence. This country visit occurs at a most fortuitous moment as the local political parties and British and Irish governments negotiate the implementation of the Stormont House Agreement and its measures for dealing with the past. For victims and survivors of the most recent period of conflict between Ireland and Britain the matters of truth, justice, acknowledgement and recognition have not been dealt with in a comprehensive manner to date. This submission will argue that they have not been dealt with in a human rights compliant manner. This submission will further argue that these matters should not be subject to internal negotiation and trade off rather than being treated as matters of governmental and societal legal and moral obligation to all of those who have suffered most during the conflict. While recognising that the matters are complex and difficult, they are nonetheless clearly identifiable, and comprehensive and compliant solutions are available, as evidenced by the copious numbers of reports and recommendations published to date, including Eolas (2003), Healing Through Remembering (2006), the Consultative Group for Dealing With the Past (2009), Haass O’Sullivan (2013) and lastly the Stormont House Agreement (2014). The visit of the Special Rapporteur is therefore most welcome at a time when the intervention of international, independence and expertise is most clearly needed and should be most valued. -

APPEARANCES the Sole Member: His Honour Judge Peter Smithwick

A P P E A R A N C E S The Sole Member: His Honour Judge Peter Smithwick For the Tribunal: Mrs. Mary Laverty, SC Mr. Justin Dillon, SC Mr. Dara Hayes, BL Mr. Fintan Valentine, BL Instructed by: Jane McKevitt Solicitor For the Commissioner of An Garda Siochana: Mr. Diarmuid McGuinness, SC Mr. Michael Durack, SC Mr. Gareth Baker, BL Instructed by: Mary Cummins CSSO For Owen Corrigan: Mr. Jim O'Callaghan, SC Mr. Darren Lehane, BL Instructed by: Fintan Lawlor Lawlor Partners Solicitors For Leo Colton: Mr. Paul Callan, SC Mr. Eamon Coffey, BL Instructed by: Dermot Lavery Solicitors For Finbarr Hickey: Fionnuala O'Sullivan, BL Instructed by: James MacGuill & Co. For the Attorney General: Ms. Nuala Butler, SC Mr. Douglas Clarke, SC Instructed by: CSSO For Freddie Scappaticci: Niall Mooney, BL Pauline O'Hare Instructed by: Michael Flanigan Solicitor For Kevin Fulton: Mr. Neil Rafferty, QC Instructed by: John McAtamney Solicitor For Breen Family: Mr. John McBurney For Buchanan Family/ Heather Currie: Ernie Waterworth McCartan Turkington Breen Solicitors NOTICE: A WORD INDEX IS PROVIDED AT THE BACK OF THIS TRANSCRIPT. THIS IS A USEFUL INDEXING SYSTEM, WHICH ALLOWS YOU TO QUICKLY SEE THE WORDS USED IN THE TRANSCRIPT, WHERE THEY OCCUR AND HOW OFTEN. EXAMPLE: - DOYLE [2] 30:28 45:17 THE WORD “DOYLE” OCCURS TWICE PAGE 30, LINE 28 PAGE 45, LINE 17 I N D E X Witness Page No. Line No. KEVIN FULTON CROSS-EXAMINED BY MR. DURACK 1 10 CROSS-EXAMINED BY MR. O'ROURKE 34 2 CROSS-EXAMINED BY MS. MULVENNA 76 18 EXAMINED BY MR. -

Irish Literature Since 1990 Examines the Diversity and Energy of Writing in a Period Marked by the Unparalleled Global Prominence of Irish Culture

BREW0009 15/5/09 11:17 am Page 1 Irish literature since 1990 Irish literature since 1990 examines the diversity and energy of writing in a period marked by the unparalleled global prominence of Irish culture. The book is distinctive in bringing together scholars from across Europe and the United States, whose work explores Irish literary culture from a rich variety of critical perspectives. This collection provides a wide-ranging survey of fiction, poetry and drama over the last two decades, considering both well-established figures and newer writers who have received relatively little critical attention before. It also considers creative work in cinema, visual culture and the performing arts. Contributors explore the central developments within Irish culture and society that have transformed the writing and reading of identity, sexuality, history and gender. The volume examines the contexts from which the literature emerges, including the impact of Mary Robinson’s presidency in the Irish Republic; the new buoyancy of the Irish diaspora, and growing cultural confidence ‘back home’; legislative reform on sexual and moral issues; the uneven effects generated by the resurgence of the Irish economy (the ‘Celtic Tiger’ myth); Ireland’s increasingly prominent role in Europe; the declining reputation of established institutions and authorities in the Republic (corruption trials and Church scandals); the Northern Ireland Peace Process, and the changing relationships it has made possible. In its breadth and critical currency, this book will be of particular BREWSTER interest to academics and students working in the fields of literature, drama and cultural studies. Scott Brewster is Director of English at the University of Salford Michael Parker is Professor of English Literature at the University of Central Lancashire AND Cover image: ‘Collecting Meteorites at Knowth, IRELANTIS’.