Submission to UN Special Rapporteur Pablo De Greiff 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

His Honour Judge Peter Smithwick for the Tribunal

A P P E A R A N C E S The Sole Member: His Honour Judge Peter Smithwick For the Tribunal: Mrs. Mary Laverty, SC Mr. Justin Dillon, SC Mr. Dara Hayes, BL Mr. Fintan Valentine, BL Instructed by: Jane McKevitt Solicitor For the Commissioner of An Garda Siochana: Mr. Diarmuid McGuinness, SC Mr. Michael Durack, SC Mr. Gareth Baker, BL Instructed by: Mary Cummins CSSO For Owen Corrigan: Mr. Jim O'Callaghan, SC Mr. Darren Lehane, BL Instructed by: Fintan Lawlor Lawlor Partners Solicitors For Leo Colton: Mr. Paul Callan, SC Mr. Eamon Coffey, BL Instructed by: Dermot Lavery Solicitors For Finbarr Hickey: Fionnuala O'Sullivan, BL Instructed by: James MacGuill & Co. For the Attorney General: Ms. Nuala Butler, SC Mr. Douglas Clarke, SC Instructed by: CSSO For Freddie Scappaticci: Eavanna Fitzgerald, BL Pauline O'Hare Instructed by: Michael Flanigan Solicitor For Kevin Fulton: Mr. Neil Rafferty, QC Instructed by: John McAtamney Solicitor For Breen Family: Mr. John McBurney For Buchanan Family/ Heather Currie: Ernie Waterworth McCartan Turkington Breen Solicitors For the PSNI: Mark Robinson, BL NOTICE: A WORD INDEX IS PROVIDED AT THE BACK OF THIS TRANSCRIPT. THIS IS A USEFUL INDEXING SYSTEM, WHICH ALLOWS YOU TO QUICKLY SEE THE WORDS USED IN THE TRANSCRIPT, WHERE THEY OCCUR AND HOW OFTEN. EXAMPLE: - DOYLE [2] 30:28 45:17 THE WORD “DOYLE” OCCURS TWICE PAGE 30, LINE 28 PAGE 45, LINE 17 I N D E X Witness Page No. Line No. OWEN CORRIGAN CROSS-EXAMINED BY MR. O'CALLAGHAN 4 1 Smithwick Tribunal - 1 August 2012 - Day 119 1 1 THE TRIBUNAL RESUMED ON THE 1ST AUGUST 2012 AS FOLLOWS: 2 3 MR. -

Identity, Authority and Myth-Making: Politically-Motivated Prisoners and the Use of Music During the Northern Irish Conflict, 1962 - 2000

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Identity, authority and myth-making: Politically-motivated prisoners and the use of music during the Northern Irish conflict, 1962 - 2000 Claire Alexandra Green Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 I, Claire Alexandra Green, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 29/04/19 Details of collaboration and publications: ‘It’s All Over: Romantic Relationships, Endurance and Loyalty in the Songs of Northern Irish Politically-Motivated Prisoners’, Estudios Irlandeses, 14, 70-82. 2 Abstract. In this study I examine the use of music by and in relation to politically-motivated prisoners in Northern Ireland, from the mid-1960s until 2000. -

Legacy Inquest Review, Mrs Justice Keegan – Sept/Oct 2019

No Case name Lawyers Brief description Readiness Likely Other of incident Disclosure Other scheduling remarks Non-sensitive Sensitive aspects 1. Neil John Family lawyers – Mr McConville, 21, from Bleary, Co Well advanced PONI material also Officer M (the killer) No clear indication – Non-legacy, Karen Quinlivan/ Armagh, was shot dead near also shot Michael year 2? though first McConville O Muirigh Lisburn by PSNI following a car Tighe + Pearse fatality by PSNI. PSNI-Ritchie pursuit in April 2003. Jordan – more cross- Victim’s partner PONI-Fee referencing required wishing to join 2. Terence Family lawyers – Shot dead on 10 May 1988. He 12 folders - still 2 folders Scope concerns by Cases to be heard in AG Ref in 2013 Fiona died after Brian Nelson sent redacting for Art 2 + 8 state. Family lawyers joint inquest with McDaid Doherty/Padraig O UDA/UFF gunmen to the wrong anxious about lack families’ agreement. Muirigh address. of system and Even though material multiple agencies, previously collected still including NIO (6 much work required 3. Gerard Slane Family lawyers – Father of three, was shot dead by 20 folders - Art 2 + 8 Public Interest Lever Arch files) and along with “robust case AG Ref in 2011 Fiona Doherty/Paul the UDA at his home at Waterville redactions done 1-18 Immunity (PII) Cabinet Office (no management”. Pierce Street, west Belfast, on 23 ongoing - folders 1-4 idea of quantity). PSNI + MoD – Mark September 1988. Nelson case complete, 16 more Keegan shares Not ready for hearing Robinson to do. concerns; orders production of a plan N.B. -

Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990

From ‘as British as Finchley’ to ‘no selfish strategic interest’: Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990 Fiona Diane McKelvey, BA (Hons), MRes Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences of Ulster University A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Ulster University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2018 I confirm that the word count of this thesis is less than 100,000 words excluding the title page, contents, acknowledgements, summary or abstract, abbreviations, footnotes, diagrams, maps, illustrations, tables, appendices, and references or bibliography Contents Acknowledgements i Abstract ii Abbreviations iii List of Tables v Introduction An Unrequited Love Affair? Unionism and Conservatism, 1885-1979 1 Research Questions, Contribution to Knowledge, Research Methods, Methodology and Structure of Thesis 1 Playing the Orange Card: Westminster and the Home Rule Crises, 1885-1921 10 The Realm of ‘old unhappy far-off things and battles long ago’: Ulster Unionists at Westminster after 1921 18 ‘For God's sake bring me a large Scotch. What a bloody awful country’: 1950-1974 22 Thatcher on the Road to Number Ten, 1975-1979 26 Conclusion 28 Chapter 1 Jack Lynch, Charles J. Haughey and Margaret Thatcher, 1979-1981 31 'Rise and Follow Charlie': Haughey's Journey from the Backbenches to the Taoiseach's Office 34 The Atkins Talks 40 Haughey’s Search for the ‘glittering prize’ 45 The Haughey-Thatcher Meetings 49 Conclusion 65 Chapter 2 Crisis in Ireland: The Hunger Strikes, 1980-1981 -

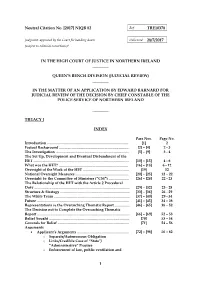

Barnard's (Edward) Application for Judicial Review of The

Neutral Citation No. [2017] NIQB 82 Ref: TRE10378 Judgment: approved by the Court for handing down Delivered: 28/7/2017 (subject to editorial corrections)* IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE IN NORTHERN IRELAND ________ QUEEN’S BENCH DIVISION (JUDICIAL REVIEW) ________ IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION BY EDWARD BARNARD FOR JUDICIAL REVIEW OF THE DECISION BY CHIEF CONSTABLE OF THE POLICE SERVICE OF NORTHERN IRELAND ________ TREACY J INDEX Para Nos. Page No. Introduction ........................................................................................ [1] 2 Factual Background ........................................................................... [2] – [4] 2 - 3 The Investigation .............................................................................. [5] – [9] 3 - 4 The Set Up, Development and Eventual Disbandment of the HET ....................................................................................................... [10] – [15] 4 - 6 What was the HET? ........................................................................... [16] – [18] 6 - 12 Oversight of the Work of the HET .................................................. [19] 12 National Oversight Measures .......................................................... [20] – [25] 12 – 22 Oversight by the Committee of Ministers (“CM”) ...................... [26] – [28] 22 - 23 The Relationship of the HET with the Article 2 Procedural Duty ....................................................................................................... [29] – [32] 23 - 25 Structure -

Extremism and Terrorism

Ireland: Extremism and Terrorism On December 19, 2019, Cloverhill District Court in Dublin granted Lisa Smith bail following an appeal hearing. Smith, a former member of the Irish Defense Forces, was arrested at Dublin Airport on suspicion of terrorism offenses following her return from Turkey in November 2019. According to Irish authorities, Smith was allegedly a member of ISIS. Smith was later examined by Professor Anne Speckhard who determined that Smith had “no interest in rejoining or returning to the Islamic State.” Smith’s trial is scheduled for January 2022. (Sources: Belfast Telegraph, Irish Post) Ireland saw an increase in Islamist and far-right extremism throughout 2019, according to Europol. In 2019, Irish authorities arrested five people on suspicions of supporting “jihadi terrorism.” This included Smith’s November 2019 arrest. An additional four people were arrested for financing jihadist terrorism. Europol also noted a rise in far-right extremism, based on the number of Irish users in leaked user data from the far-right website Iron March. (Source: Irish Times) Beginning in late 2019, concerns grew that the possible return of a hard border between British-ruled Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland after Brexit could increase security tensions in the once war-torn province. The Police Services of Northern Ireland recorded an increase in violent attacks along the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland border in 2019 and called on politicians to take action to heal enduring divisions in society. According to a representative for the New IRA—Northern Ireland’s largest dissident organization—the uncertainty surrounding Brexit provided the group a politicized platform to carry out attacks along the U.K. -

Dziadok Mikalai 1'St Year Student

EUROPEAN HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY Program «World Politics and economics» Dziadok Mikalai 1'st year student Essay Written assignment Course «International relations and governances» Course instructor Andrey Stiapanau Vilnius, 2016 The Troubles (Northern Ireland conflict 1969-1998) Plan Introduction 1. General outline of a conflict. 2. Approach, theory, level of analysis (providing framework). Providing the hypothesis 3. Major actors involved, definition of their priorities, preferences and interests. 4. Origins of the conflict (historical perspective), major actions timeline 5. Models of conflicts, explanations of its reasons 6. Proving the hypothesis 7. Conclusion Bibliography Introduction Northern Ireland conflict, called “the Troubles” was the most durable conflict in the Europe since WW2. Before War in Donbass (2014-present), which lead to 9,371 death up to June 3, 20161 it also can be called the bloodiest conflict, but unfortunately The Donbass War snatched from The Troubles “the victory palm” of this dreadful competition. The importance of this issue, however, is still essential and vital because of challenges Europe experience now. Both proxy war on Donbass and recent terrorist attacks had strained significantly the political atmosphere in Europe, showing that Europe is not safe anymore. In this conditions, it is necessary for us to try to assume, how far this insecurity and tensions might go and will the circumstances and the challenges of a international relations ignite the conflict in Northern Ireland again. It also makes sense for us to recognize that the Troubles was also a proxy war to a certain degree 23 Sources, used in this essay are mostly mass-media articles, human rights observers’ and international organizations reports, and surveys made by political scientists on this issue. -

Tom Vaughan Lawlor Barry Ward Martin Mccann

TOM VAUGHAN LAWLOR BARRY WARD MARTIN MCCANN DIRECTED BY STEPHEN BURKE 2017 / 93 MIN / IRELAND / ENGLISH / PRISON THRILLER Sales Contact: 173 Richardson Street, Brooklyn, NY 11222 USA Office: +1.718.312.8210 Fax: +1.718.362.4865 Email: [email protected] Web: www.visitfilms.com LOGLINE Based on the true story of the 1983 mass break-out of 38 prisoners from the HMP Maze high security prison, Maze is a gripping prison break film that follows the relationship between two men on oppo- site sides of the prison bars. SYNOPSIS Maze charts how inmate Larry Marley, played by Tom Vaughan-Lawlor (Love / Hate), becomes chief architect of the largest prison escape in Europe since World War II – an escape which he plans but does not go on himself. Up against him is the most state-of-the-art and secure prison in the whole of Europe - a prison within a prison. While scheming his way towards pulling off this feat, Larry comes into close contact with prison warder Gordon Close, played by Barry Ward (Jimmy’s Hall). Larry and Gordon’s complex journey begins with cautious, chess-like moves. Initially, Gordon holds all the power in their relationship and rejects all of Larry’s attempts at establishing a friendship be- tween them. Bit by bit, Larry wears down Gordon’s defenses, maneuvering himself into a position of trust. As each man begins to engage with the other as an equal, the barrier between prisoner and warder has been broken. During all this time, however, Larry has been scheming behind Gordon’s back, gleaning as much information as he can and working with other prisoners in a separate block, trying to engineer their escape. -

The Edge of Extinction: Travels with Enduring People in Vanishing

THE EDGE OF EXTINCTION Th e Edge of Extinction TRAVELS WITH ENDURING PEOPLE IN VANISHING LANDS M jules pretty Comstock Publishing Associates a division of Cornell University Press Ithaca and London Copyright © 2014 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2014 by Cornell University Press Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pretty, Jules N., author. Th e Edge of extinction : travels with enduring people in vanishing lands / Jules Pretty. pages cm Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8014-5330-4 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Nature—Eff ect of human beings on—Moral and ethical aspects. 2. Human beings—Eff ect of environment on—Moral and ethical aspects. I. Title. GF80.P73 2014 304.2—dc23 2014017464 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fi bers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu . Cloth printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 { iv } For My father, John Pretty (1932–2012), and mother, Susan and Gill, Freya, and Th eo Without my journey And without this spring I would have missed this dawn. -

Over Ten Years of Cover-Ups Left Nineteen People Dead

Irelandclick.com January 22 2007 Site Search DailyIreland.com Advanced Home As of 11th April 2006, www.dailyireland.com, incorporating www.irelandclick.com is Registered with ABC ELECTRONIC (www.abce.org.uk) and supports industry agreed standards for website News traffic measurement Comment Sport Over ten years of cover-ups left nineteen Features people dead ------------------------- RUC’s Special Branch gave Mount Vernon UVF a licence to kill Lá North Belfast News ------------------------- By Ciaran Barnes Downloads 19/01/2007 ------------------------- Andersonstown News 17 January 1993, Sharon McKenna: Two former policemen claim Mark Haddock told them he shot Shraon Home McKenna dead at the house of an elderly Protestant friend on the Shore Road. News Jonty Brown and Trevor McIlwrath claim Special Branch blocked attempts Comment by them to charge the UVF men involved despite the detectives having the confession. Sport Features 24 February 1994, Sean McParland: Murdered by a UVF Special Branch agent from Newtownabbey nicknamed ------------------------- the Beast. The paramilitary is the current boss of the organisation in Southeast Antrim. North Belfast News No one has been charged with the killing. Home News 17 May 1994, Eamon Fox and Gary Convie: The Catholic builders were allegedly shot dead by Haddock as they worked on a building site in Tiger's Comment Bay. Despite admitting to Special Branch handlers that he was involved Haddock was never charged. Sport Features 17 June 1994, Cecil Dougherty and William Corrigan: The Protestant builders were shot dead in a hut on a construction site in Rathcoole. They ------------------------- were mistaken for Catholics. South Belfast News The killing was carried out by a paramilitary who was trying to wrest control of the Southeast Antrim UVF from Haddock, shooting the men while Home his boss was on holiday. -

UNITED Kingdompolitical Killings in Northern Ireland EUR 45/001/94 TABLE of CONTENTS

UNITED KINGDOMPolitical Killings in Northern Ireland EUR 45/001/94 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 Killings by members of the security forces ........................................................... 3 Investigative Procedures: practice and standards ...................................... 8 The Use of Lethal Force: Laws and Regulations/International Standards ..................................................................................... 12 Collusion between security forces and armed groups ........................................ 14 The Stevens Inquiry 1989-90 ..................................................................... 14 The Case of Brian Nelson .......................................................................... 16 The Killing of Patrick Finucane .................................................................. 20 The Stevens Inquiry 1993 .......................................................................... 23 Other Allegations of Collusion .................................................................... 25 Amnesty International's Concerns about Allegations of Collusion ............ 29 Killings by Armed Political Groups ...................................................................... 34 Introduction ................................................................................................. 34 Human Rights Abuses by Republican Armed Groups .............................. 35 IRA Bombings -

Double Blind

Double Blind The untold story of how British intelligence infiltrated and undermined the IRA Matthew Teague, The Atlantic, April 2006 Issue https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2006/04/double-blind/304710/ I first met the man now called Kevin Fulton in London, on Platform 13 at Victoria Station. We almost missed each other in the crowd; he didn’t look at all like a terrorist. He stood with his feet together, a short and round man with a kind face, fair hair, and blue eyes. He might have been an Irish grammar-school teacher, not an IRA bomber or a British spy in hiding. Both of which he was. Fulton had agreed to meet only after an exchange of messages through an intermediary. Now, as we talked on the platform, he paced back and forth, scanning the faces of passersby. He checked the time, then checked it again. He spoke in an almost impenetrable brogue, and each time I leaned in to understand him, he leaned back, suspicious. He fidgeted with several mobile phones, one devoted to each of his lives. “I’m just cautious,” he said. He lives in London now, but his wife remains in Northern Ireland. He rarely goes out, for fear of bumping into the wrong person, and so leads a life of utter isolation, a forty-five-year-old man with a lot on his mind. During the next few months, Fulton and I met several times on Platform 13. Over time his jitters settled, his speech loosened, and his past tumbled out: his rise and fall in the Irish Republican Army, his deeds and misdeeds, his loyalties and betrayals.