The Edge of Extinction: Travels with Enduring People in Vanishing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weavers' Way Short Walk 10 (Of 11) Halvergate to Berney Arms

S10 Weavers’ Way Short Walk 10 (of 11) Halvergate to Berney Arms www.norfolktrails.co.uk Version Date: December 2013 Along the way Walk summary A walk through the flat open landscape of Halvergate Marshes, rich with wildlife and windmills, that ends at one of the most The route begins in the village of Halvergate and leads along Marsh Road past the thatched Red remote railway stations in the country. Lion pub out onto the Halvergate Marshes. The marshes were part of a great estuary in Roman times but the area was drained and settled in the early medieval period and now makes up the Getting started largest expanse of grazing marsh in East Anglia. The whole area is designated as a site of This walk starts in Halvergate at Squires special scientific interest and has several international designations too. The marshes support Road/Marsh Road junction (TG420069) and ends internationally important numbers of wintering Bewick’s swan and populations of other waders at Berney Arms rail station (TG460053). and wildfowl that include ruff, golden plover, lapwing, bean goose, European white-fronted goose and wigeon. Other species breeding on Halvergate Marshes include snipe, oystercatcher, yellow Getting there Train Berney Arms Rail Station request stop on wagtail and bearded tit; short-eared and barn owls are frequent winter visitors. limited service. More trains on Sundays. National Rail enquiries: 08457 484950. A little less than a mile out of Halvergate, the Weavers’ Way leads away from the road and along www.nationalrail.co.uk a path to cross Halvergate Fleet, a salt marsh watercourse that the former road to Yarmouth Bus service used to run along until the construction of the Acle New Road (Acle Straight) in the 1830s. -

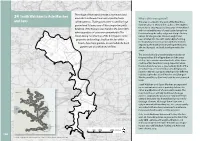

24 South Walsham to Acle Marshes and Fens

South Walsham to Acle Marshes The village of Acle stands beside a vast marshland 24 area which in Roman times was a great estuary Why is this area special? and Fens called Gariensis. Trading ports were located on high This area is located to the west of the River Bure ground and Acle was one of those important ports. from Moulton St Mary in the south to Fleet Dyke in Evidence of the Romans was found in the late 1980's the north. It encompasses a large area of marshland with considerable areas of peat located away from when quantities of coins were unearthed in The the river along the valley edge and along tributary Street during construction of the A47 bypass. Some valleys. At a larger scale, this area might have properties in the village, built on the line of the been divided into two with Upton Dyke forming beach, have front gardens of sand while the back the boundary between an area with few modern impacts to the north and a more fragmented area gardens are on a thick bed of flints. affected by roads and built development to the south. The area is basically a transitional zone between the peat valley of the Upper Bure and the areas of silty clay estuarine marshland soils of the lower reaches of the Bure these being deposited when the marshland area was a great estuary. Both of the areas have nature conservation area designations based on the two soil types which provide different habitats. Upton Broad and Marshes and Damgate Marshes and Decoy Carr have both been designated SSSIs. -

Broads (2006) IDB Water Level Management Plans: Summary

Broads (2006) IDB Water Level Management Plans: Summary WLMP Date reviewed Agreed (Lou WLMP Title (with Author Board Designated Site Designation Mayer/Clive English Doarks) Nature) SSSI, SAC, SPA, Calthorpe Broad RAMSAR, Heidi Brograve 2001 2005 Broads IDB NNR Mahon SSSI, SAC, Upper Thurne Broads SPA, & Marshes RAMSAR, SSSI, SAC, Mike Upper Thurne Broads Catfield 2001 2005 Broads IDB SPA, Harding & Marshes RAMSAR, SSSI, SAC, Mike Chapelfield 2001 2005 Broads IDB Ant Broads & Marshes SPA, Harding RAMSAR, SSSI, SAC, Halvergate Marshes , SPA, RAMSAR, Heidi SSSI, SAC, Mahon / Halvergate 2000 2005 Broads IDB Damgate Marshes SPA, Sandie RAMSAR, Tolhurst SSSI, SAC, Decoy Carr , SPA, RAMSAR, SSSI, SAC, Burgh Common SPA, Muckfleet Marshes RAMSAR, Hemsby and John 2000 2005 Broads IDB SSSI, SAC, Muckfleet Harpley Hall Farm Fen SPA, RAMSAR Trinity Broads SSSI, SAC SSSI, SAC, Priory Meadows , SPA, Heidi RAMSAR, Hickling 2001 2005 Broads IDB Mahon SSSI, SAC, Upper Thurne Broads SPA, & Marshes RAMSAR, SSSI, SAC, John Horning 1998 2005 Broads IDB Alderfen Broad SPA, Harpley RAMSAR, SSSI, SAC, John Ludham – Potter SPA, Horsefen 1999 2005 Broads IDB Harpley Heigham Marshes RAMSAR, NNR SSSI, SAC, Upper Thurne Broads SPA, John & Marshes Horsey 2000 2005 Broads IDB RAMSAR,s Harpley Winterton To Horsey SSSI, SAC Dunes SSSI, SAC, Ludham Bridge John 1999 2005 Broads IDB Ant Broads & Marshes SPA, East Harpley RAMSAR, SSSI, SAC, John Upper Thurne Broads Martham 2002 2005 Broads IDB SPA, Harpley & Marshes RAMSAR, SSSI, SAC, John Ludham – Potter SPA, Potter Heigham -

Norton Marshes to Haddiscoe Dismantled

This area inspired the artist Sir J. A. Arnesby 16 Yare Valley - Norton Marshes to Brown (1866-1955) who lived each summer Haddiscoe Dismantled Railway at The White House, Haddiscoe. Herald of the Night, Sir J.A.Arnesby-Brown Why is this area special? This is a vast area of largely drained marshland which lies to the south of the Rivers Yare and Waveney. It traditionally formed part of the parishes of Norton (Subcourse), Thurlton, Thorpe and Haddiscoe along with a detached part of Raveningham. It would have had a direct connection to what is now known as Haddiscoe Island, prior to the construction of the New Cut which connected the Yare and Waveney together to avoid having to travel across Breydon Water. There are few houses within this marshland area. Those that exist are confined to those locations 27 where there were, or are transport links across NORFOLK the rivers. The remainder of the settlements have 30 28 developed in a linear way hugging the edges of the southern river valley side. 22 31 23 29 The Haddiscoe Dam road provides the main 24 26 connection north-south from Haddiscoe village to 25 NORWICH St Olaves. 11 20 Gt YARMOUTH 10 12 19 21 A journey on the train line from Norwich to 14 9 Lowestoft which follows the line of the New Cut 13 15 18 16 and then hugs the northern side of the Waveney 17 Valley provides a glorious way to view this area as 8 7 public rights of way into the middle of the marshes LOWESTOFT 6 4 (other than the fully navigable river) are few and 2 3 1 5 far between. -

Download Tales from the Emporium for FREE

Tales from the Emporium The life and times of the Whittlecreek and Eaton St Torpid Heritage Railway and Sal T. Marsh's Emporium Bob Trubshaw Welcome to more tales from an imaginary heritage railway in the top left-hand corner of Norfolk with rolling stock inspired by Rowland Emett’s cartoons of the 1940s and 50s. Truth to tell the author doesn’t get overly excited by locomotives or station buildings, although wagons and carriages occasionally arouse curiosity. His real interest is in the bigger picture of railways: why they were created, how they dealt with the local terrain, what influence they had on local farming, industry and settlements, and so forth. And that extends to 'heritage' railways: how they acquire funding, how they promote themselves as places of interest, and how they interact with other tourist attractions in the vicinity. The Whittlecreek and Eaton St Torpid Heritage Railway employs a General Manager (who does not like being called ‘The General’), a formidable Property Manager (who does like to be referred to as ‘The PM’), a witticism-infested Operations Manager who socialises each week with the neophobic Workshop Manager, and a Gift Shop Manager (deemed ‘nice but useless’). The railway staff interact with the somewhat overbearing curator of the nearby Arts Centre and two young sisters who create and sell pots at the Wonky Pot Emporium – when not chatting to customers or learning about some arcane aspects of Daoism. Paranormal vigils in the ruins of a twelfth century castle, the creation of a heritage museum focused on the former sand mining in the area, sightings of inexplicable big cats – or are they phantom black dogs? – in the fields nearby, and the preparations for a Viking festival all unknowingly converge on the dodgy dealings of the proprietor of the local canoe hire facility (named after a one-time local lass called Pocahontas). -

A Study of the Tales As Printed in Folk-Lore in 1891

2060302 INVESTIGATING THE LEGENDS OF THE CARRS: A STUDY OF THE TALES AS PRINTED IN FOLK-LORE IN 1891 Maureen James A submission presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Glamorgan/Prifysgol Morgannwg For the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Volume 1 April 2013 Abstract This study investigates the content, collection and dissemination of the Legends of the Cars, a group of tales published in Folk-Lore in 1891, as having been collected in North Lincolnshire from local people. The stories, have been criticised for their relatively unique content and the collector, Marie Clothilde Balfour has been accused of creating the tales. The stories are today used by artists, writers and storytellers, wishing to evoke the flatland and beliefs of the past, yet despite the questions raised regarding authenticity, neither the collector, the context or the contents have been thoroughly investigated. The tales have also, due to their inclusion in diverse collections, moved geographically south in the popular perception. This thesis documents the research into the historical, geographical and social context of the Legends of the Cars, and also validates the folkloric content and the dialect as being from North Lincolnshire. The situation within the early Folklore Society prior to, and after the publication of the stories, has also been investigated, to reveal a widespread desire to collect stories from the rural populations, particularly if they demonstrated a latent survival of paganism. Balfour followed the advice of the folklorists and, as well as submitting the tales in dialect, also acknowledged their pagan content within her introductions. -

Rock, Cherry Creek, Nannie Creek

Rock, Cherry and Narmie r-teks 3rhw t ;MeA o;- Watershed Analysis A 13.2: R 6 2/2x Winema National Forest - / TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. DESCRIPTION OF THE WATERSHED AREA 1 A. Location and Land Management 1 B. Geology 7 C. Climate 9 D. Soils 9 E. Hydrology 10 F. Potential Vegetation 10 III. BENEFICIAL USES AND VALUES 12 A. Biodiversity 12 B. Wilderness/Research Natural Area 12 C. Recreation 12 D. Cultural Resources 13 E. Timber and Roads 14 F. Agriculture and Water Source 14 G. Mineral Resources 15 H. Aesthetic/Scenic Values 15 IV. ISSUES TO BE EVALUATED 16 V. ANALYSIS OF ISSUES 17 A. Forest Health Decline 17 B. Wildlife and Plant Habitat Alteration 22 C. Fish Stocking in Subalpine Lakes 29 D. Impact to Native Fish Populations 31 E. Fish Habitat Degradation 36 F. Channel Condition Alteration 41 G. Hydrograph Change 45 H. Increased Sediment Loading 56 VI. MANAGEMENT RECOMMENDATIONS AND RESTORATION OPPORTUNITIES 63 A. Upland Forests 63 B. Low Elevation Wetlands 63 C. Fish/Aquatic Habitats 64 D. Roads and Channel Morphology 64 E. Trails 67 F. Riparian Reserves 67 G. Geomorphological Reserves 69 H. Soils 69 VII. REFERENCES 70 VIII. APPENDICES A. List of People Consulted 74 B. Wildlife Species 75 C. Plant and Fungi Species 80 D. Source of Vegetation Data 89 |&j0hERN OflEGOX~@NUND~IVEAQ UORARY WATERSHED ANALYSIS REPORT FOR THE ROCK, CHERRY. AND NANNIE CREEK WATERSHED AREA I. INTRODUCTION This report documents an analysis of the Rock, Cherry, and Nannie Watershed Area. The purpose of the analysis is to develop a scientifically-based understanding of the processes and interactions occurring within the watershed area and the effects of management practices. -

Lost Floodplain Wetland Environments and Efforts to Restore Connectivity, Habitat, and Water Quality Settings on the Great Barrier Reef

fmars-06-00071 February 25, 2019 Time: 15:47 # 1 POLICY AND PRACTICE REVIEWS published: 26 February 2019 doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00071 Lost Floodplain Wetland Environments and Efforts to Restore Connectivity, Habitat, and Water Quality Settings on the Great Barrier Reef Nathan J. Waltham1,2*, Damien Burrows1, Carla Wegscheidl3, Christina Buelow1,2, Mike Ronan4, Niall Connolly3, Paul Groves5, Donna Marie-Audas5, Colin Creighton1 and Marcus Sheaves1,2 1 Centre for Tropical Water and Aquatic Ecosystem Research, College of Science and Engineering, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD, Australia, 2 Science for Integrated Coastal Ecosystem Management, School of Marine Biology and Aquaculture, College of Science and Engineering, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD, Australia, 3 Rural Economic Development, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Queensland Government, Townsville, QLD, Australia, 4 Department of Environment and Science, Queensland Government, Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 5 Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, Australian Government, Townsville, QLD, Australia Edited by: Mario Barletta, Departamento de Oceanografia da Managers are moving toward implementing large-scale coastal ecosystem restoration Universidade Federal de Pernambuco projects, however, many fail to achieve desired outcomes. Among the key reasons for (UFPE), Brazil this is the lack of integration with a whole-of-catchment approach, the scale of the Reviewed by: A. Rita Carrasco, project (temporal, spatial), the requirement for on-going costs for maintenance, the Universidade do Algarve, Portugal lack of clear objectives, a focus on threats rather than services/values, funding cycles, Jacob L. Johansen, New York University Abu Dhabi, engagement or change in stakeholders, and prioritization of project sites. Here we United Arab Emirates critically assess the outcomes of activities in three coastal wetland complexes positioned *Correspondence: along the catchments of the Great Barrier Reef (GBR) lagoon, Australia, that have Nathan J. -

Special Status Vascular Plant Surveys and Habitat Modeling in Yosemite National Park, 2003–2004

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Special Status Vascular Plant Surveys and Habitat Modeling in Yosemite National Park, 2003–2004 Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SIEN/NRTR—2010/389 ON THE COVER USGS and NPS joint survey for Tompkins’ sedge (Carex tompkinsii), south side Merced River, El Portal, Mariposa County, California (upper left); Yosemite onion (Allium yosemitense) (upper right); Yosemite lewisia (Lewisia disepala) (lower left); habitat model for mountain lady’s slipper (Cypripedium montanum) in Yosemite National Park, California (lower right). Photographs by: Peggy E. Moore. Special Status Vascular Plant Surveys and Habitat Modeling in Yosemite National Park, 2003–2004 Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SIEN/NRTR—2010/389 Peggy E. Moore, Alison E. L. Colwell, and Charlotte L. Coulter U.S. Geological Survey Western Ecological Research Center 5083 Foresta Road El Portal, California 95318 October 2010 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Program Center publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series provides contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. -

Ephemerality of Discrete Methane Vents in Lake Sediments

Ephemerality of discrete methane vents in lake sediments The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Scandella, Benjamin P.; Pillsbury, Liam; Weber, Thomas; Ruppel, Carolyn; Hemond, Harold F. and Juanes, Ruben. “Ephemerality of Discrete Methane Vents in Lake Sediments.” Geophysical Research Letters 43, 9 (May 2016): 4374–4381 © 2016 American Geophysical Union As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/2016GL068668 Publisher American Geophysical Union (AGU) Version Final published version Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/110359 Terms of Use Article is made available in accordance with the publisher's policy and may be subject to US copyright law. Please refer to the publisher's site for terms of use. Geophysical Research Letters RESEARCH LETTER Ephemerality of discrete methane vents in lake sediments 10.1002/2016GL068668 Benjamin P. Scandella1, Liam Pillsbury2, Thomas Weber2, Carolyn Ruppel3,4, Harold F. Hemond1, Key Points: and Ruben Juanes1,4 • We present direct high-resolution, months-long measurements of 1Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, methane venting from lake sediments USA, 2Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of New Hampshire, Durham, New Hampshire, USA, 3U.S. • We show that gas vents are 4 ephemeral and not persistent as Geological Survey, Woods Hole, Massachusetts, USA, Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences, previously assumed Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA • Our study provides an unprecedented detailed view of the spatiotemporal signature of methane flux Abstract Methane is a potent greenhouse gas whose emission from sediments in inland waters and shallow oceans may both contribute to global warming and be exacerbated by it. -

2020 PDF Guide

Your premier LGBTQIA+ arts and culture festival 19 JAN – 9 FEB 194 events • 22 days midsumma.org.au 2020 1 2 3 #midsumma midsumma.org.au Welcome About Midsumma Judy Small Aaron Martin Foley MP Sally Capp Rachel Slade Midsumma Festival Co-Chair Minister for Creative Industries Lord Mayor of Melbourne Chief Customer Experience Officer & Midsumma Festival is Australia’s premier queer arts and cultural O’Shannessy Minister for Equality Executive Co-Sponsor, NAB Pride organisation, bringing together a diverse mix of LGBTQIA+ artists, Midsumma Festival Co-Chair performers, communities and audiences. In Victoria, we begin every year with a The colour and joy of the Midsumma Festival We’re back again this year and we’re looking celebration of pride. shines in January and the City of Melbourne forward to another successful Midsumma Every January, Midsumma Festival expands over 22 days of summer Welcome to Midsumma Festival 2020! We are thrilled to welcome you with an explosion of queer events that spring forth from the welcomes the brilliant atmosphere and Festival. It’s always a great time of year to on behalf of the Midsumma board as its first co-chairs. We recognise Each Midsumma, Victoria’s LGBTIQ underground, fringe, and mainstream, at the very forefront of local, community pride it brings. connect and celebrate with our community. the amazing contribution to the festival of our predecessor John communities come together to celebrate national and international queer culture. The Midsumma Festival Caldwell and assure you we will do our best -

Acts • Port Fairy Folk MUSIC Festival – 1977 to 2016

International Boys of the Lough (Scotland) Acts • Port Fairy Folk MUSIC National Abominable Snow Band, Acacia Trio, Boys of The Lough, Barefoot Nellie, John Beavis, Festival – 1977 to 2016 Ted Egan , Captain Moonlight, Bernard Carney, There are around 3500 acts that have been Elizabeth Cohen, Christy Cooney, Alfirio Cristaldo, booked, programmed and played at Port Fairy John Crowl, Dave Diprose, Five N' A Zak, Fruitcake since 1977. of Australian Stories, Stan Gottschalk, Rose No-one has actually counted all of them. Many Harvey, Greg Hastings, High Time String Band, Street Performers and workshop acts have not Richard Keame, Jindivick, Stephen Jones, been listed here. Sebastian Jorgensen, Tony Kishawi, Jamie Lawrence, Di McNicol, Malarkey, Muddy Creek December 2 - 4th 1977 Bush Band, The New Dancehall Racketeers, Tom Declan Affley, Tipplers All, Poteen, Nick Mercer, Nicholson, Trevor Pickles, Shades of Troopers Bush Turkey, Flying Pieman and many more Creek, Gary Shields, Judy Small, Danny Spooner, Shenanigans, Sirocco, Tara, Mike O'Rourke, Tam O December 1- 3rd 1978 Shanter, Tim O' Brien, Ian Paulin, Pibroch, Shirley Declan Affley, Buckley's Bush Band, John Power, Cathy O'Sullivan and Cleis Pearce, Poteen, MacAuslan, Poteen, Rum Buggery and The Lash Tansey's Fancy, Rick E Vengeance, Lisa Young Trio, Kel Watkins, Tim Whelan, Fay White, Stephen December 7 -9th 1979 Whiteside, Witchwood, Geoff Woof, Yabbies Redgum, Finnegans Wake, Poteen, Mick and Helen Flanagan, Tim O'Brien and Captain Moonlight, March 8 - 11th 1985 Buckley's Bush Band,