Jour Al of Co Temporary Asia Quarterly Volume 38

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thailand's Red Networks: from Street Forces to Eminent Civil Society

Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Freiburg (Germany) Occasional Paper Series www.southeastasianstudies.uni-freiburg.de Occasional Paper N° 14 (April 2013) Thailand’s Red Networks: From Street Forces to Eminent Civil Society Coalitions Pavin Chachavalpongpun (Kyoto University) Pavin Chachavalpongpun (Kyoto University)* Series Editors Jürgen Rüland, Judith Schlehe, Günther Schulze, Sabine Dabringhaus, Stefan Seitz The emergence of the red shirt coalitions was a result of the development in Thai politics during the past decades. They are the first real mass movement that Thailand has ever produced due to their approach of directly involving the grassroots population while campaigning for a larger political space for the underclass at a national level, thus being projected as a potential danger to the old power structure. The prolonged protests of the red shirt movement has exceeded all expectations and defied all the expressions of contempt against them by the Thai urban elite. This paper argues that the modern Thai political system is best viewed as a place dominated by the elite who were never radically threatened ‘from below’ and that the red shirt movement has been a challenge from bottom-up. Following this argument, it seeks to codify the transforming dynamism of a complicated set of political processes and actors in Thailand, while investigating the rise of the red shirt movement as a catalyst in such transformation. Thailand, Red shirts, Civil Society Organizations, Thaksin Shinawatra, Network Monarchy, United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship, Lèse-majesté Law Please do not quote or cite without permission of the author. Comments are very welcome. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the author in the first instance. -

Thailand White Paper

THE BANGKOK MASSACRES: A CALL FOR ACCOUNTABILITY ―A White Paper by Amsterdam & Peroff LLP EXECUTIVE SUMMARY For four years, the people of Thailand have been the victims of a systematic and unrelenting assault on their most fundamental right — the right to self-determination through genuine elections based on the will of the people. The assault against democracy was launched with the planning and execution of a military coup d’état in 2006. In collaboration with members of the Privy Council, Thai military generals overthrew the popularly elected, democratic government of Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, whose Thai Rak Thai party had won three consecutive national elections in 2001, 2005 and 2006. The 2006 military coup marked the beginning of an attempt to restore the hegemony of Thailand’s old moneyed elites, military generals, high-ranking civil servants, and royal advisors (the “Establishment”) through the annihilation of an electoral force that had come to present a major, historical challenge to their power. The regime put in place by the coup hijacked the institutions of government, dissolved Thai Rak Thai and banned its leaders from political participation for five years. When the successor to Thai Rak Thai managed to win the next national election in late 2007, an ad hoc court consisting of judges hand-picked by the coup-makers dissolved that party as well, allowing Abhisit Vejjajiva’s rise to the Prime Minister’s office. Abhisit’s administration, however, has since been forced to impose an array of repressive measures to maintain its illegitimate grip and quash the democratic movement that sprung up as a reaction to the 2006 military coup as well as the 2008 “judicial coups.” Among other things, the government blocked some 50,000 web sites, shut down the opposition’s satellite television station, and incarcerated a record number of people under Thailand’s infamous lèse-majesté legislation and the equally draconian Computer Crimes Act. -

Thailand's Moment of Truth — Royal Succession After the King Passes Away.” - U.S

THAILAND’S MOMENT OF TRUTH A SECRET HISTORY OF 21ST CENTURY SIAM #THAISTORY | VERSION 1.0 | 241011 ANDREW MACGREGOR MARSHALL MAIL | TWITTER | BLOG | FACEBOOK | GOOGLE+ This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. This story is dedicated to the people of Thailand and to the memory of my colleague Hiroyuki Muramoto, killed in Bangkok on April 10, 2010. Many people provided wonderful support and inspiration as I wrote it. In particular I would like to thank three whose faith and love made all the difference: my father and mother, and the brave girl who got banned from Burma. ABOUT ME I’m a freelance journalist based in Asia and writing mainly about Asian politics, human rights, political risk and media ethics. For 17 years I worked for Reuters, including long spells as correspondent in Jakarta in 1998-2000, deputy bureau chief in Bangkok in 2000-2002, Baghdad bureau chief in 2003-2005, and managing editor for the Middle East in 2006-2008. In 2008 I moved to Singapore as chief correspondent for political risk, and in late 2010 I became deputy editor for emerging and frontier Asia. I resigned in June 2011, over this story. I’ve reported from more than three dozen countries, on every continent except South America. I’ve covered conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Lebanon, the Palestinian Territories and East Timor; and political upheaval in Israel, Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand and Burma. Of all the leading world figures I’ve interviewed, the three I most enjoyed talking to were Aung San Suu Kyi, Xanana Gusmao, and the Dalai Lama. -

Bomb Planted at ASTV

Volume 17 Issue 20 News Desk - Tel: 076-273555 May 15 - 21, 2010 Daily news at www.phuketgazette.net 25 Baht The Gazette is published in association with Bomb planted at ASTV Leaders react to grenade at ‘yellow-shirt’ TV station PAPER bag contain- told the Gazette that the grenade INSIDE ing a live hand grenade was not the work of the red shirts. was found hanging “There is conflict within the Afrom the front door of PAD itself. For example, some the ASTV ‘yellow-shirt’ television PAD leaders have turned into network office in Phuket Town ‘multi-colors’. That’s a point to on May 11. consider, too,” he said. Bomb disposal police safely Phuket Provincial Police removed the device, an M67 Commander Pekad Tantipong said fragmentation grenade with its pin the act was probably the work of still in place, shortly after it was an individual or small group. discovered at 9am. It had been “I don’t believe this was wrapped in electrical tape and ordered by the red shirt leaders placed in a box inside a brown in Bangkok…I’m confident in Bank on Bird paper shopping bag that read saying this will not affect tour- As Ironman Les Bird’s Alpine “Save the World”. ism at all,” he said. climb nears, find out how he’s When detonated, an M67 Sarayuth Mallam, vice been preparing. has an average ‘casualty radius’ president of the Phuket Tourist Page 10 of 15 meters and a ‘fatality ra- Association, was less confident. dius’ of five meters; fragments CALM AND COLLECTED: A bomb disposal expert shows the M67 grenade. -

Board of Editors

2020-2021 Board of Editors EXECUTIVE BOARD Editor-in-Chief KATHERINE LEE Managing Editor Associate Editor KATHRYN URBAN KYLE SALLEE Communications Director Operations Director MONICA MIDDLETON CAMILLE RYBACKI KOCH MATTHEW SANSONE STAFF Editors PRATEET ASHAR WENDY ATIENO KEYA BARTOLOMEO Fellows TREVOR BURTON SABRINA CAMMISA PHILIP DOLITSKY DENTON COHEN ANNA LOUGHRAN SEAMUS LOVE IRENE OGBO SHANNON SHORT PETER WHITENECK FACULTY ADVISOR PROFESSOR NANCY SACHS Thailand-Cambodia Border Conflict: Sacred Sites and Political Fights Ihechiluru Ezuruonye Introduction “I am not the enemy of the Thai people. But the [Thai] Prime Minister and the Foreign Minister look down on Cambodia extremely” He added: “Cambodia will have no happiness as long as this group [PAD] is in power.” - Cambodian PM Hun Sen Both sides of the border were digging in their heels; neither leader wanted to lose face as doing so could have led to a dip in political support at home.i Two of the most common drivers of interstate conflict are territorial disputes and the politicization of deep-seated ideological ideals such as religion. Both sources of tension have contributed to the emergence of bloody conflicts throughout history and across different regions of the world. Therefore, it stands to reason, that when a specific geographic area is bestowed religious significance, then conflict is particularly likely. This case study details the territorial dispute between Thailand and Cambodia over Prasat (meaning ‘temple’ in Khmer) Preah Vihear or Preah Vihear Temple, located on the border between the two countries. The case of the Preah Vihear Temple conflict offers broader lessons on the social forces that make religiously significant territorial disputes so prescient and how national governments use such conflicts to further their own political agendas. -

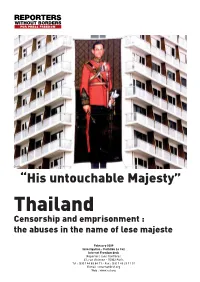

Thailand Censorship and Emprisonment : the Abuses in the Name of Lese Majeste

© AFP “His untouchable Majesty” Thailand Censorship and emprisonment : the abuses in the name of lese majeste February 2009 Investigation : Clothilde Le Coz Internet Freedom desk Reporters sans frontières 47, rue Vivienne - 75002 Paris Tel : (33) 1 44 83 84 71 - Fax : (33) 1 45 23 11 51 E-mail : [email protected] Web : www.rsf.org “But there has never been anyone telling me "approve" because the King speaks well and speaks correctly. Actually I must also be criticised. I am not afraid if the criticism concerns what I do wrong, because then I know. Because if you say the King cannot be criticised, it means that the King is not human.”. Rama IX, king of Thailand, 5 december 2005 Thailand : majeste and emprisonment : the abuses in name of lese Censorship 1 It is undeniable that King Bhumibol According to Reporters Without Adulyadej, who has been on the throne Borders, a reform of the laws on the since 5 May 1950, enjoys huge popularity crime of lese majeste could only come in Thailand. The kingdom is a constitutio- from the palace. That is why our organisa- nal monarchy that assigns him the role of tion is addressing itself directly to the head of state and protector of religion. sovereign to ask him to find a solution to Crowned under the dynastic name of this crisis that is threatening freedom of Rama IX, Bhumibol Adulyadej, born in expression in the kingdom. 1927, studied in Switzerland and has also shown great interest in his country's With a king aged 81, the issues of his suc- agricultural and economic development. -

A Coup Ordained? Thailand's Prospects for Stability

A Coup Ordained? Thailand’s Prospects for Stability Asia Report N°263 | 3 December 2014 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Thailand in Turmoil ......................................................................................................... 2 A. Power and Legitimacy ................................................................................................ 2 B. Contours of Conflict ................................................................................................... 4 C. Troubled State ............................................................................................................ 6 III. Path to the Coup ............................................................................................................... 9 A. Revival of Anti-Thaksin Coalition ............................................................................. 9 B. Engineering a Political Vacuum ................................................................................ 12 IV. Military in Control ............................................................................................................ 16 A. Seizing Power -

The External Relations of the Monarchy in Thai Politics

Aalborg Universitet The external relations of the monarchy in Thai politics Schmidt, Johannes Dragsbæk Publication date: 2007 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Schmidt, J. D. (2007). The external relations of the monarchy in Thai politics. Paper presented at International conference on "Royal charisma, military power and the future of democracy in Thailand", Copenhagen, Denmark. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. ? Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. ? You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ? You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from vbn.aau.dk on: September 29, 2021 The external relations of the monarchy in Thai politics1 Tentative draft – only for discussion Johannes Dragsbaek Schmidt2 The real political problem in Siam was – and is - precisely this: that there was no decisive popular break with ’absolutism’, fuelled by social radicalism and mass nationalism (Anderson 1978: 225) The September 19 military coup in Thailand in 2006 caught most observers by surprise. -

Making Sense of the Military Coup D'état in Thailand

Aktuelle Südostasienforschung Current Research on Southeast Asia The Iron Silk Road and the Iron Fist: Making Sense of the Military Coup D’État in Thailand Wolfram Schaffar ► Schaffar, W. (2018). The iron silk road and the iron fist: Making sense of the military coup d’état in Thailand. Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 11(1), 35-52. In May of 2014, the military of Thailand staged a coup and overthrew the democrati- cally elected government of Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra. The political divisions in Thailand, which culminated in the coup, as well as the course of events leading to the coup, are difficult to explain via Thai domestic policy and the power relations -be tween Thailand’s military, corporate, and civil entities. The divisions can be more clearly revealed when interpreted in the context of the large-scale Chinese project “One Belt, One Road”. This ambitious infrastructure project represents an important step in the rise of China to the position of the world’s biggest economic power and – drawing on world-systems theory – to the center of a new long accumulation cycle of the global econ- omy. Against this backdrop, it will be argued that developments in Thailand can be in- terpreted historically as an example of the upheavals in the periphery of China, the new center. The establishment of an autocratic system is, however, not directly attributable to the influence of China, but results from the interplay of internal factors in Thailand. Keywords: Belt-and-Road Initiative; Coup D’État; High-Speed Train; Thailand; World-Systems Theory THE RETURN OF AUTHORITARIANISM IN THAILAND On 22 May 2014, the military in Thailand staged a coup d’état and removed the elected government of Yingluck Shinawatra, the sister of the exiled former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra.1 This coup marked the climax of the politi- cal division of Thailand into two camps: the Yellow Shirts, which are close to www.seas.at doi 10.14764/10.ASEAS-2018.1-3 www.seas.at the monarchy and to the royalist-conservative elites, and the Red Shirts, who support Thaksin. -

The Political Role of Business Magnates in Competitive Authoritarian Regimes

Jahrbuch für Wirtschaftsgeschichte 2019; 60(2): 299–334 Heiko Pleines The Political Role of Business Magnates in Competitive Authoritarian Regimes. A Comparative Analysis https://doi.org/10.1515/jbwg-2019-3001 Abstract: This contribution examines the role of business magnates (“oli- garchs”) in political transitions away from competitive authoritarianism and towards either full authoritarianism or democracy. Based on 65 cases of compet- itive authoritarian regimes named in the academic literature, 24 historical cases with politically active business magnates are identified for further investigation. The analysis shows that in about half of those cases business magnates do not have a distinct impact on political regime change, as they are tightly integrated into the ruling elites. If they do have an impact, they hamper democratization at an early stage, making a transition to full democracy a rare exception. At the same time, a backlash led by the ruling elites against manipulation through business magnates makes a transition to full autocracy more likely than in competitive authoritarian regimes without influential business magnates. JEL-Codes: D 72, D 74, N 40, P 48 Keywords: Business magnates, economic elites, political regime trajectories, competitive authoritarianism, Großunternehmer, Wirtschaftseliten, Entwick- lungspfade politischer Regime 1 Introduction Wealthy businesspeople who are able to influence political decisions acting on their own are in many present and historical cases treated as “grey eminences” who hold considerable political power. While it is obvious that they influence specific policies, their impact on political regime change is less clear. This ques- tion is especially relevant for so-called “soft”, i.e. electoral or competitive au- || Heiko Pleines, (Prof. -

(Title of the Thesis)*

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Huddersfield Repository University of Huddersfield Repository Treewai, Pichet Political Economy of Media Development and Management of the Media in Bangkok Original Citation Treewai, Pichet (2015) Political Economy of Media Development and Management of the Media in Bangkok. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/26449/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ POLITICAL ECONOMY OF MEDIA DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF THE MEDIA IN BANGKOK PICHET TREEWAI A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Strategy, Marketing and Economics The University of Huddersfield March 2015 Abstract This study is important due to the crucial role of media in the dissemination of information, especially in emerging economies, such as Thailand. -

FULLTEXT01.Pdf

Essential reading for anyone interested in ai politics and culture e ai monarchy today is usually presented as both guardian of tradition and the institution to bring modernity and progress to the ai people. It is moreover Saying the seen as protector of the nation. Scrutinizing that image, this volume reviews the fascinating history of the modern monarchy. It also analyses important cultural, historical, political, religious, and legal forces shaping Saying the Unsayable Unsayable the popular image of the monarchy and, in particular, of King Bhumibol Adulyadej. us, the book o ers valuable Monarchy and Democracy insights into the relationships between monarchy, religion and democracy in ailand – topics that, a er the in Thailand September 2006 coup d’état, gained renewed national and international interest. Addressing such contentious issues as ai-style democracy, lése majesté legislation, religious symbolism and politics, monarchical traditions, and the royal su ciency economy, the book will be of interest to a Edited by broad readership, also outside academia. Søren Ivarsson and Lotte Isager www.niaspress.dk Unsayable-pbk_cover.indd 1 25/06/2010 11:21 Saying the UnSayable Ivarsson_Prels_new.indd 1 30/06/2010 14:07 NORDIC INSTITUTE OF ASIAN STUDIES NIAS STUDIES IN ASIAN TOPICS 32 Contesting Visions of the Lao Past Christopher Goscha and Søren Ivarsson (eds) 33 Reaching for the Dream Melanie Beresford and Tran Ngoc Angie (eds) 34 Mongols from Country to City Ole Bruun and Li Naragoa (eds) 35 Four Masters of Chinese Storytelling