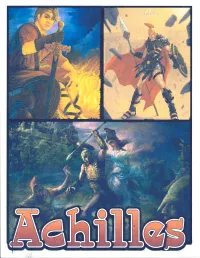

Thetis and Cheiron in Thessaly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cave of the Nymphs at Pharsalus Brill Studies in Greek and Roman Epigraphy

The Cave of the Nymphs at Pharsalus Brill Studies in Greek and Roman Epigraphy Editorial Board John Bodel (Brown University) Adele Scafuro (Brown University) VOLUME 6 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bsgre The Cave of the Nymphs at Pharsalus Studies on a Thessalian Country Shrine By Robert S. Wagman LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Pharsala. View of the Karapla hill and the cave of the Nymphs from N, 1922 (SAIA, Archivio Fotografico B 326) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Wagman, Robert S. Title: The Cave of the Nymphs at Pharsalus : studies on a Thessalian country shrine / by Robert S. Wagman. Description: Boston : Brill, 2015. | Series: Brill studies in Greek and Roman epigraphy, ISSN 1876-2557 ; volume 6 | Includes bibliographical references and indexes. Identifiers: LCCN 2015032381| ISBN 9789004297616 (hardback : alk. paper) | ISBN 9789004297623 (e-book) Subjects: LCSH: Thessaly (Greece)—Antiquities. | Excavations (Archaeology)—Greece—Thessaly. | Inscriptions—Greece—Thessaly. | Farsala (Greece)—Antiquities. | Excavations (Archaeology)—Greece—Farsala. | Inscriptions—Greece—Farsala. | Nymphs (Greek deities) Classification: LCC DF221.T4 W34 2015 | DDC 938/.2—dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015032381 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, ipa, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 1876-2557 isbn 978-90-04-29761-6 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-29762-3 (e-book) Copyright 2016 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi and Hotei Publishing. -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

Critical Evaluation of Risks and Opportunities for OPERANDUM Oals

Ref. Ares(2020)72894 - 07/01/2020 OPEn-air laboRAtories for Nature baseD solUtions to Manage hydro-meteo risks Critical evaluation of risks and opportunities for OPERANDUM OALs Deliverable information Deliverable no.: D1.2 Work package no.: 01 Document version: V01 Document Preparation Date: 18.11.2019 Responsibility: Partner No. 7 – UNIVERSITY OF SURREY This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 776848 GA no.: 776848 Project information Project acronym and name: OPERANDUM - OPEn-air laboRAtories for Nature baseD solUtions to Manage hydro-meteo risks EC Grant Agreement no.: 776848 Project coordinator: UNIBO Project start date: 01.07.2018 Duration: 48 months Document Information & Version Management Document title: Critical evaluation of risks and opportunities for OPERANDUM OALs Document type: Report Main author(s): Sisay Debele (UoS), Prashant Kumar (UoS), Jeetendra Sahani (UoS), Paul Bowyer (HZG), Julius Pröll (HZG), Swantje Preuschmann (HZG), Slobodan B. Mickovski (GCU), Liisa Ukonmaanaho (LUKE), Nikos Charizopoulos (AUA-PSTE), Michael Loupis (KKT-ITC), Thomas Zieher (OEAW), Martin Rutzinger (OEAW), Glauco Gallotti (UNIBO), Leonardo Aragão (UNIBO), Leonardo Bagaglini (UNIBO), Maria Stefanopoulou (KKT-ITC), Depy Panga (KKT-ITC), Leena Finér (LUKE), Eija Pouta (LUKE), Marco A. Santo (UNIBO), Natalia Korhonen (FMI), Francesco Pilla (UCD), Arunima Sarkar (UCD), Bidroha Basu (UCD) Contributor(s): - Reviewed by: Fabrice Renaud (UoG) and Federico Porcù -

Tensions in the Greek Symposium Julia Burns Submitted in Fulfillment

Conflicting Desires and Unstable Identities: Tensions in the Greek Symposium Julia Burns Submitted in Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in Classical Studies May 2013 ©2013 Julia Burns I. Introduction The Greek symposium, or private drinking party, was a formal context for the consumption of wine, often accompanied by the enactment of ritual activities or other associated forms of entertainment.1 The tradition of symposia seems to have evolved from group feasts in the Archaic period and from the traditional gathering of hetaireiai in the late Archaic period.2 Generally, men would congregate in the andron of a private home and recline on kline for a night of drinking, singing or poetry composition, discussion, or other games.3 While meals that shared aspects of the Archaic symposium were held in public spaces in Athens by the fifth century, symposia remained the preserve of the elites: the aristocracy had a monopoly on sympotic symbolic capital, despite any popularizing elements of polis-wide feasting.4 The term “symposium” is often used synecdochically for the series of ritual activities that takes place over the course of a single gathering; however, it more accurately relates to the time when wine was consumed during a private party. If food was prepared before the drinking began, this meal, the deipnon, was a distinct and separate ritual element of the party.5 After the consumption of food, a hymn was sung in honor of the gods and libations were poured. At this point, the master of ceremonies, called the symposiarch, would decide the proper ratio at which 1 I would like to thank Kate Gilhuly for her support and invaluable comments on drafts of this paper. -

Hesiod Theogony.Pdf

Hesiod (8th or 7th c. BC, composed in Greek) The Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are probably slightly earlier than Hesiod’s two surviving poems, the Works and Days and the Theogony. Yet in many ways Hesiod is the more important author for the study of Greek mythology. While Homer treats cer- tain aspects of the saga of the Trojan War, he makes no attempt at treating myth more generally. He often includes short digressions and tantalizes us with hints of a broader tra- dition, but much of this remains obscure. Hesiod, by contrast, sought in his Theogony to give a connected account of the creation of the universe. For the study of myth he is im- portant precisely because his is the oldest surviving attempt to treat systematically the mythical tradition from the first gods down to the great heroes. Also unlike the legendary Homer, Hesiod is for us an historical figure and a real per- sonality. His Works and Days contains a great deal of autobiographical information, in- cluding his birthplace (Ascra in Boiotia), where his father had come from (Cyme in Asia Minor), and the name of his brother (Perses), with whom he had a dispute that was the inspiration for composing the Works and Days. His exact date cannot be determined with precision, but there is general agreement that he lived in the 8th century or perhaps the early 7th century BC. His life, therefore, was approximately contemporaneous with the beginning of alphabetic writing in the Greek world. Although we do not know whether Hesiod himself employed this new invention in composing his poems, we can be certain that it was soon used to record and pass them on. -

1 Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer's Iliad Senior Thesis

Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer’s Iliad Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Undergraduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Classical Studies Professor Joel Christensen, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts By Joana Jankulla May 2018 Copyright by Joana Jankulla 1 Copyright by Joana Jankulla © 2018 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Joel Christensen. Thank you, Professor Christensen for guiding me through this process, expressing confidence in me, and being available whenever I had any questions or concerns. I would not have been able to complete this work without you. Secondly, I would like to thank Professor Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Professor Cheryl Walker for reading my thesis and providing me with feedback. The Classics Department at Brandeis University has been an instrumental part of my growth in my four years as an undergraduate, and I am eternally thankful to all the professors and staff members in the department. Thank you to my friends, specifically Erica Theroux, Sarah Jousset, Anna Craven, Rachel Goldstein, Taylor McKinnon and Georgie Contreras for providing me with a lot of emotional support this year. I hope you all know how grateful I am for you as friends and how much I have appreciated your love this year. Thank you to my mom for FaceTiming me every time I was stressed about completing my thesis and encouraging me every step of the way. Finally, thank you to Ian Leeds for dropping everything and coming to me each time I needed it. -

1 | Page the LIGHTNING THIEF Percy Jackson and the Olympians

THE LIGHTNING THIEF Percy Jackson and the Olympians - Book 1 Rick Riordan 1 | Page 1 I ACCIDENTALLY VAPORIZE MY PRE-ALGEBRA TEACHER Look, I didn't want to be a half-blood. If you're reading this because you think you might be one, my advice is: close this book right now. Believe what-ever lie your mom or dad told you about your birth, and try to lead a normal life. Being a half-blood is dangerous. It's scary. Most of the time, it gets you killed in painful, nasty ways. If you're a normal kid, reading this because you think it's fiction, great. Read on. I envy you for being able to believe that none of this ever happened. But if you recognize yourself in these pages-if you feel something stirring inside-stop reading immediately. You might be one of us. And once you know that, it's only a mat-ter of time before they sense it too, and they'll come for you. Don't say I didn't warn you. My name is Percy Jackson. I'm twelve years old. Until a few months ago, I was a boarding student at Yancy Academy, a private school for troubled kids in upstate New York. 2 | Page Am I a troubled kid? Yeah. You could say that. I could start at any point in my short miserable life to prove it, but things really started going bad last May, when our sixth-grade class took a field trip to Manhattan- twenty-eight mental-case kids and two teachers on a yellow school bus, heading to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to look at ancient Greek and Roman stuff. -

University of Groningen the Sacrifice of Pregnant Animals Bremmer, Jan N

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Groningen University of Groningen The Sacrifice of Pregnant Animals Bremmer, Jan N. Published in: Greek Sacrificial Ritual: Olympian and Chthonian IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2005 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Bremmer, J. N. (2005). The Sacrifice of Pregnant Animals. In B. Alroth, & R. Hägg (Eds.), Greek Sacrificial Ritual: Olympian and Chthonian (pp. 155-165). Gothenburg: Paul Astroms Forlag. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 12-11-2019 THE SACRIFICE OF PREGNANT ANIMALS by JAN N. BREMMER There has recently been renewed interest in Olympian sacrifice and its chthonian counterparts, 1 but much less attention has been paid to its more unusual variants. -

The Hecate of the Theogony Jenny Strauss Clay

STRAUSS CALY, JENNY, The Hecate of the "Theogony" , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 25:1 (1984) p.27 The Hecate of the Theogony Jenny Strauss Clay EAR THE MIDDLE of the Theogony, Hesiod appears to drop N everything in order to launch into an extended encomium of Hecate (411-52). Because of its length and apparent lack of integration into its context, but above all because of the peculiar terms of praise reserved for the goddess, the so-called "Hymn to Hecate" has often been dismissed as an intrusion into the Hesiodic text.l To be sure, voices have also been raised in defense,2 and, at present, the passage stands unbracketed in the editions of Mazon, Solmsen, and West.3 But questions remain even if the authenticity of the lines is acknowledged. Why does Hesiod devote so much space to so minor a deity? What is the origin and function of Hesiod's Hecate, and what role does she play in the poem ?4 1 Most notably by U. von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, Der Glaube der Hellenen I (Berlin 1931) 172. Wilamowitz is followed by M. P. Nilsson, Geschichte der griechischen Re/igion 3 I (Munich 1969) 723. Condemnation is fairly universal among earlier editors. Cf 0. Gruppe, Ueber die Theogonie des Hesiod (Berlin 1841) 72; G. Schoemann, Die He siodische Theogonie (Berlin 1868) 190, who, after many good observations, concludes that the passage is a later interpolation; H. Flach, Die Hesiodische Theogonie (Berlin 1873) 81; A. Fick, Hesiods Gedichte (Gottingen 1887) 17 ("Der Verfasser war ein Or phiker"); F. -

New Achilles Folder.Pdf

ffi ffi Achilles (uh-KlH-leez) was a mighty Greek hero. r. Greeks and Romans told many stories about him. The stories said that Achilles could not be harmed. He was i: ',' , ; \: i ", : : The stories also said that gods helped Achilles and other heroes. During one battle, a hero named Hector threw his spear at Achilles. The goddess Athena (uh-THEE-nuh) knocked the spear down. Then Achilles raised his spear to throw at Hector. But the god Apollo created a fog around Hector. Achilles could not see Hector. Hector ran from Achilles. As Hector ran, Athena approached him. She had i: r i i, ,. , :,: ,'. , herself as one of his brothers. So Hector stopped. Athena offered him a new spear, but it was a trick. When Hector reached for the spear, it disappeared. Achilles then caught up to Hector. He attacked and killed Hector. Achilles defeated many enemies in battle. Achilles' mother was Thetis (THEE-tuhss). She was a sea : ' . Nymphs were creatures that never grew old or died. They w€re : . Achilles' father was the human King Peleus (PEE-1ee-uhss). Peleus ruled an area of Greece called Phthia (THYE-uh). Because Achilles was part human, he would grow old and die. He was : ,, ,, . Thetis wanted to keep Achilles from dying of old age. At night, Thetis put Achilles into a fire to burn off his mortal skin. In the morning, she rubbed ambrosia (am-BRoH-zhuh) on him to heal his body. Ambrosia was the food of the gods. Achilles' mother also wanted to protect her son from harm. -

Leto As Mother: Representations of Leto with Apollo and Artemis in Attic Vase Painting of the Fifth Century B.C

https://publications.dainst.org iDAI.publications ELEKTRONISCHE PUBLIKATIONEN DES DEUTSCHEN ARCHÄOLOGISCHEN INSTITUTS Dies ist ein digitaler Sonderdruck des Beitrags / This is a digital offprint of the article Lavinia Foukara Leto as Mother: Representations of Leto with Apollo and Artemis in Attic Vase Painting of the Fifth Century B.C. aus / from Archäologischer Anzeiger Ausgabe / Issue Seite / Page 63–83 https://publications.dainst.org/journals/aa/2027/6626 • urn:nbn:de:0048-journals.aa-2017-1-p63-83-v6626.5 Verantwortliche Redaktion / Publishing editor Redaktion der Zentrale | Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Weitere Informationen unter / For further information see https://publications.dainst.org/journals/aa ISSN der Online-Ausgabe / ISSN of the online edition 2510-4713 ISSN der gedruckten Ausgabe / ISSN of the printed edition Verlag / Publisher Ernst Wasmuth Verlag GmbH & Co. Tübingen ©2019 Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Zentrale, Podbielskiallee 69–71, 14195 Berlin, Tel: +49 30 187711-0 Email: [email protected] / Web: dainst.org Nutzungsbedingungen: Mit dem Herunterladen erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen (https://publications.dainst.org/terms-of-use) von iDAI.publications an. Die Nutzung der Inhalte ist ausschließlich privaten Nutzerinnen / Nutzern für den eigenen wissenschaftlichen und sonstigen privaten Gebrauch gestattet. Sämtliche Texte, Bilder und sonstige Inhalte in diesem Dokument unterliegen dem Schutz des Urheberrechts gemäß dem Urheberrechtsgesetz der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Die Inhalte können von Ihnen nur dann genutzt und vervielfältigt werden, wenn Ihnen dies im Einzelfall durch den Rechteinhaber oder die Schrankenregelungen des Urheberrechts gestattet ist. Jede Art der Nutzung zu gewerblichen Zwecken ist untersagt. Zu den Möglichkeiten einer Lizensierung von Nutzungsrechten wenden Sie sich bitte direkt an die verantwortlichen Herausgeberinnen/Herausgeber der entsprechenden Publikationsorgane oder an die Online-Redaktion des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts ([email protected]). -

THE DIONYSIAN PARADE and the POETICS of PLENITUDE by Professor Eric Csapo 20 February 2013 ERIC CSAPO

UCL DEPARTMENT OF GREEK AND LATIN HOUSMAN LECTURE UCL Housman Lecture THE DIONYSIAN PARADE AND THE POETICS OF PLENITUDE by Professor Eric Csapo 20 February 2013 ERIC CSAPO A.E. Housman (1859–1936) Born in Worcestershire in 1859, Alfred Edward Housman was a gifted classical scholar and poet. After studying in Oxford, Housman worked for ten years as a clerk, while publishing and writing scholarly articles on Horace, Propertius, Ovid, Aeschylus, Euripides and Sophocles. He gradually acquired such a high reputation that in 1892 he returned to the academic world as Professor of Classics at University College London (1892–1911) and then as Kennedy Professor of Latin at Trinity College, Cambridge (1911–1936). Housman Lectures at UCL The Department of Greek and Latin at University College London organizes regular Housman Lectures, named after its illustrious former colleague (with support from UCL Alumni). Housman Lectures, delivered by a scholar of international distinction, originally took place every second year and now happen every year, alternating between Greek and Roman topics (Greek lectures being funded by the A.G. Leventis Foundation). The fifth Housman lecture, which was given by Professor Eric Csapo (Professor of Classics, University of Sydney) on 20 February 2013, is here reproduced with minor adjustments. This lecture and its publication were generously supported by the A.G. Leventis Foundation. 2 HOUSMAN LECTURE The Dionysian Parade and the Poetics of Plenitude Scholarship has treated our two greatest Athenian festivals very differently.1 The literature on the procession of the Panathenaea is vast. The literature on the Parade (pompe) of the Great Dionysia is miniscule.