Studies in Comparative Federalism: West Germany (M-128)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Godesberg Programme and Its Aftermath

Karim Fertikh The Godesberg Programme and its Aftermath A Socio-histoire of an Ideological Transformation in European Social De- mocracies Abstract: The Godesberg programme (1959) is considered a major shift in European social democratic ideology. This article explores its genesis and of- fers a history of both the written text and its subsequent uses. It does so by shedding light on the organizational constraints and the personal strategies of the players involved in the production of the text in the Social Democra- tic Party of Germany. The article considers the partisan milieu and its trans- formations after 1945 and in the aftermaths of 1968 as an important factor accounting for the making of the political myth of Bad Godesberg. To do so, it explores the historicity of the interpretations of the programme from the 1950s to the present day, and highlights the moments at which the meaning of Godesberg as a major shift in socialist history has become consolidated in Europe, focusing on the French Socialist Party. Keywords: Social Democracy, Godesberg Programme, socio-histoire, scienti- fication of politics, history of ideas In a recent TV show, “Baron noir,” the main character launches a rant about the “f***g Bad Godesberg” advocated by the Socialist Party candidate. That the 1950s programme should be mentioned before a primetime audience bears witness to the widespread dissemination of the phrase in French political culture. “Faire son Bad Godesberg” [literally, “doing one’s Bad Godesberg”] has become an idiomatic French phrase. It refers to a fundamental alteration in the core doctrinal values of a politi- cal party (especially social-democratic and socialist ones). -

Landeszentrale Für Politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg, Director: Lothar Frick 6Th Fully Revised Edition, Stuttgart 2008

BADEN-WÜRTTEMBERG A Portrait of the German Southwest 6th fully revised edition 2008 Publishing details Reinhold Weber and Iris Häuser (editors): Baden-Württemberg – A Portrait of the German Southwest, published by the Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg, Director: Lothar Frick 6th fully revised edition, Stuttgart 2008. Stafflenbergstraße 38 Co-authors: 70184 Stuttgart Hans-Georg Wehling www.lpb-bw.de Dorothea Urban Please send orders to: Konrad Pflug Fax: +49 (0)711 / 164099-77 Oliver Turecek [email protected] Editorial deadline: 1 July, 2008 Design: Studio für Mediendesign, Rottenburg am Neckar, Many thanks to: www.8421medien.de Printed by: PFITZER Druck und Medien e. K., Renningen, www.pfitzer.de Landesvermessungsamt Title photo: Manfred Grohe, Kirchentellinsfurt Baden-Württemberg Translation: proverb oHG, Stuttgart, www.proverb.de EDITORIAL Baden-Württemberg is an international state – The publication is intended for a broad pub- in many respects: it has mutual political, lic: schoolchildren, trainees and students, em- economic and cultural ties to various regions ployed persons, people involved in society and around the world. Millions of guests visit our politics, visitors and guests to our state – in state every year – schoolchildren, students, short, for anyone interested in Baden-Würt- businessmen, scientists, journalists and numer- temberg looking for concise, reliable informa- ous tourists. A key job of the State Agency for tion on the southwest of Germany. Civic Education (Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg, LpB) is to inform Our thanks go out to everyone who has made people about the history of as well as the poli- a special contribution to ensuring that this tics and society in Baden-Württemberg. -

Central Europe

Central Europe West Germany FOREIGN POLICY wTHEN CHANCELLOR Ludwig Erhard's coalition government sud- denly collapsed in October 1966, none of the Federal Republic's major for- eign policy goals, such as the reunification of Germany and the improvement of relations with its Eastern neighbors, with France, NATO, the Arab coun- tries, and with the new African nations had as yet been achieved. Relations with the United States What actually brought the political and economic crisis into the open and hastened Erhard's downfall was that he returned empty-handed from his Sep- tember visit to President Lyndon B. Johnson. Erhard appealed to Johnson for an extension of the date when payment of $3 billion was due for military equipment which West Germany had bought from the United States to bal- ance dollar expenses for keeping American troops in West Germany. (By the end of 1966, Germany paid DM2.9 billion of the total DM5.4 billion, provided in the agreements between the United States government and the Germans late in 1965. The remaining DM2.5 billion were to be paid in 1967.) During these talks Erhard also expressed his government's wish that American troops in West Germany remain at their present strength. Al- though Erhard's reception in Washington and Texas was friendly, he gained no major concessions. Late in October the United States and the United Kingdom began talks with the Federal Republic on major economic and military problems. Relations with France When Erhard visited France in February, President Charles de Gaulle gave reassurances that France would not recognize the East German regime, that he would advocate the cause of Germany in Moscow, and that he would 349 350 / AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK, 1967 approve intensified political and cultural cooperation between the six Com- mon Market powers—France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. -

African-Americans with German Connections

African‐Americans with German Connections These portraits were created to introduce students, parents, and school administrators to the many African‐American leaders with German connections. Many people are not aware of the connections between Germany and Historically Black Colleges and Universities and important movements in African‐American history such as the founding of the NAACP. Too often school personnel question why a student of color would want to learn German or be interested in German‐speaking countries. These portraits tell why some people did, and show the deep history of people of color learning and using German. A second purpose of these portraits is to convey to visitors to a classroom that all students are welcome and have a place there. Images by themselves are only a small part of the classroom experience, but they do serve an important purpose. A second set of these portraits can be printed and hung up around the school. Students can use them in a “scavenger” hunt, looking for people from different time periods, from different areas of studies, etc. Students could have a list of names depicted in the portraits and move around the classroom noting information from two or three of the portraits. They could learn about the others by asking classmates to provide information about those individuals in a question/answer activity. The teacher can put two slips of paper with each name in a bag and have students draw names. The students then find the portrait of the name they have drawn and practice the alphabet by spelling the portrayed individual’s name in German or asking and answering questions about the person. -

The Visitation of Alois Ersin, S.J., to the Province of Lower Germany in 1931

Chapter 10 The Visitation of Alois Ersin, S.J., to the Province of Lower Germany in 1931 Klaus Schatz, S.J. Translated by Geoffrey Gay 1 Situation and Problems of the Province Around the year 1930, the Lower German province of the Society of Jesus was expanding but not without problems and internal tensions.1 The anti-Jesuit laws passed in 1872 during the Kulturkampf had been abrogated in 1917.2 The Weimar Constitution of 1919 had dismantled the final barriers that still existed between the constituent elements of Germany and granted religious freedom. The German province numbered 1,257 members at the beginning of 1921, when the province was divided into two: the Lower German (Germania Inferior) and the Upper German (Germania Superior), known informally as the northern and southern provinces. The southern or Upper German province, with Munich as its seat, comprised Jesuit communities in the states of Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden, and Saxony. These consisted of Munich (three residences), Aschaffen- burg, Nuremberg, Straubing, Rottmannshöhe (a retreat house), Stuttgart, and Dresden. The northern or Lower German province, with Cologne as its seat, was spread over the whole of northern Germany and included the territory of Prussia and the smaller states of northern Germany (of which only Hamburg had a Jesuit residence). At the time of the division, the new province contained fifteen residences: Münster in Westphalia, Dortmund, Essen, Duisburg, Düs- seldorf, Aachen, Cologne, Bonn, Bad Godesberg (Aloisiuskolleg), Waldesruh, 1 See Klaus Schatz, S.J., Geschichte der deutschen Jesuiten 1814–1983, 5 vols. (Münster/W.: Aschendorff, 2013) for greater detail. -

[email protected] Www

Unterkunftsverzeichnis der Stadt Bonn sortiert nach den Stadtbezirken: Bonn, Bad Godesberg, Beuel, Hardtberg Kat. * Hotel hotel Telefon Telefax Internet-Adresse Preise/Price Zimmer Adresse address telephone fax Website in € number 02 28 02 28 eMail EZ/SGL of e-mail DZ/DBL rooms BONN HG 3* Acora Hotel und Wohnen 66 86 0 66 20 20 www.acora-bonn.de EZ 53-95 120 (A) Westpreußenstraße 20-30 [email protected] DZ 65-107 53119 Bonn-Tannenbusch HG 3* Aigner 60 40 60 6 04 06 70 www.hotel-aigner-bonn.de EZ 69-102 42 (A) Dorotheenstraße 12 [email protected] DZ 88-109 53111 Bonn-Nordstadt HR 4* Ameron Hotel Königshof 26 01 0 2 60 15 29 www.hotel-koenigshof-bonn.de EZ 69-219 129 Adenauerallee 9 [email protected] DZ 109-249 53111 Bonn-Zentrum HG 3* Ameron Hotel My Poppelsdorf 26 91 0 26 10 70 www.mypoppelsdorf.com EZ 58-128 45 Wallfahrtsweg 4 [email protected] DZ 78-148 53115 Bonn-Poppelsdorf AP 3* Ameron Hotel My Südstadt 85 45 0 85 45 41 9 www.mysuedstadt.com EZ 54-138 36 Kaiserstraße 221 [email protected] DZ 74-148 53113 Bonn-Südstadt HG 3* Am Römerhof 60 41 80 63 38 38 www.hotel-roemerhof-bonn.de EZ 65-85 26 (A) Römerstraße 20 [email protected] DZ 90-100 53111 Bonn-Castell HG Am Roonplatz 91 19 30 9 11 93 30 www.hotel-am-roonplatz.de EZ 63-73 14 Argelanderstraße 91 [email protected] DZ 80-90 53115 Bonn-Südstadt AP 4* Apartmenthotel Kaiser Karl 98 14 19 99 98 14 19 98 www.apartment-hotel-bonn.de EZ ab 84 25 Vorgebirsstraße 56 [email protected] DZ ab 94 53119 Bonn-Nordtstadt HG 3* Astoria -

16 November 2018 in Bonn, Germany

United Nations/Germany High Level Forum: The way forward after UNISPACE+50 and on Space2030 13 – 16 November 2018 in Bonn, Germany USEFUL INFORMATION FOR PARTICIPANTS Content: 1. Welcome to Bonn! ..................................................................................................................... 2 2. Venue of the Forum and Social Event Sites ................................................................................. 3 3. How to get to the Venue of the Forum ....................................................................................... 4 4. How to get to Bonn from International Airports ......................................................................... 5 5. Visa Requirements and Insurance .............................................................................................. 6 6. Recommended Accommodation ............................................................................................... 6 7. General Information .................................................................................................................. 8 8. Organizing Committe ............................................................................................................... 10 Bonn, Rhineland Germany Bonn Panorama © WDR Lokalzeit Bonn 1. Welcome to Bonn! Bonn - a dynamic city filled with tradition. The Rhine and the Rhineland - the sounds, the music of Europe. And there, where the Rhine and the Rhineland reach their pinnacle of beauty lies Bonn. The city is the gateway to the romantic part of -

Mennonite Life

MENNONITE LIFEJUNE 1991 In this Issue The Mennonite encounter with National Socialism in the 1930s and 1940s remains a troubling event in Mennonite history, even as the memory of World War II and the Holocaust continue to sear the conscience of Western civilization. How could such evil happen? How could people of good will be so compromised? Mennonites have been a people of two kingdoms. Their loyalty to Christ’s kingdom has priority, but they also believe and confess, in the words of the Dortrecht Confession (1632) that “ God has ordained power and authority, and set them to punish the evil, and protect the good, to govern the world, and maintain countries and cities with their subjects in good order and regulation.” The sorting out of heavenly and worldly allegiances has never been simple. Rulers in all times and places, from Phillip II in the Spanish Netherlands to George Bush in the Persian Gulf region, have claimed to fulfill a divine mandate. In his time Adolf Hitler offered protection from anarchy and from communism. There should be no surprise that some Mennonites, especially recent victims of Russian Communism, found the National Socialist program attractive. In this issue three young Mennonite scholars, all of whom researched their topics in work toward master’s degrees, examine the Mennonite response to National Socialism in three countries: Paraguay, Germany, and Canada. John D. Thiesen, archivist at Mennonite Library and Archives at Bethel College, recounts the story as it unfolded in Paraguay. This article is drawn from his thesis completed at Wichita State University in 1990. -

The Failed Post-War Experiment: How Contemporary Scholars Address the Impact of Allied Denazification on Post-World War Ii Germany

John Carroll University Carroll Collected Masters Essays Master's Theses and Essays 2019 THE FAILED POST-WAR EXPERIMENT: HOW CONTEMPORARY SCHOLARS ADDRESS THE IMPACT OF ALLIED DENAZIFICATION ON POST-WORLD WAR II GERMANY Alicia Mayer Follow this and additional works at: https://collected.jcu.edu/mastersessays Part of the History Commons THE FAILED POST-WAR EXPERIMENT: HOW CONTEMPORARY SCHOLARS ADDRESS THE IMPACT OF ALLIED DENAZIFICATION ON POST-WORLD WAR II GERMANY An Essay Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies College of Arts & Sciences of John Carroll University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Alicia Mayer 2020 As the tide changed during World War II in the European theater from favoring an Axis victory to an Allied one, the British, American, and Soviet governments created a plan to purge Germany of its Nazi ideology. Furthermore, the Allies agreed to reconstruct Germany so a regime like the Nazis could never come to power again. The Allied Powers met at three major summits at Teheran (November 28-December 1,1943), Yalta (February 4-11, 1945), and Potsdam (July 17-August 2, 1945) to discuss the occupation period and reconstruction of all aspects of German society. The policy of denazification was agreed upon by the Big Three, but due to their political differences, denazification took different forms in each occupation zone. Within all four Allied zones, there was a balancing act between denazification and the urgency to help a war-stricken population in Germany. This literature review focuses specifically on how scholars conceptualize the policy of denazification and its legacy on German society. -

Germany at the Pivot

Three powerful factors military dy l Kenne security, trade opportunities, and Pau by Ostpolitik—are shaping West German tos attitudes toward the Soviet bloc. —Pho Germany at the Pivot BY VINCENT P. GRIMES N ONE critical issue after an- tional approach are West German O other—arms control, East- economic and military power within West trade, modernization of NATO and the German perception NATO nuclear weapons, policy to- that a historic opportunity exists to ward eastern Europe—West Ger- ease national problems. many is now exerting a major and The rise of a powerhouse econo- perhaps decisive influence. my in the Federal Republic, far from The nation of 61,000,000 seems concentrating German attention on increasingly ready to place itself at internal affairs, has fed German odds with key allies on the basic readiness to play a more prominent security issue of how to respond to international role. Soviet power. Bonn consistently After World War II, Germany lay outpaces both the US and Britain in destroyed, and the lines of occupa- supporting Soviet leader Mikhail tion became the frontiers of a divid- Gorbachev and in calling for West- ed Europe. From this prostrate con- ern military concessions. dition, the West German state has The West German Air Force's first-rate equipment includes 165 Tornado fighter/ Bonn's actions reflect a desire for risen to become a worldwide indus- ground-attack aircraft. This Tornado and a larger role in eastern Europe, a trial giant and the dominant eco- crew recently visited Andrews AFB, Md., region where the Kremlin faces vast nomic force on the Continent. -

Weisenburger 3

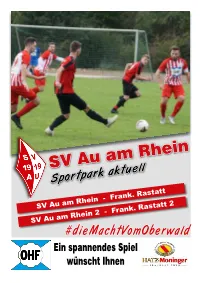

SV Au am Rhein Sportpark aktuell SV Au am Rhein - Frank. Rastatt SV Au am Rhein 2 - Frank. Rastatt 2 #dieMachtVomOberwald Ein spannendes Spiel wünscht Ihnen SV Au am Rhein - Werbepartner Vorwort der Vorstandschaft Liebe Gäste des SV Au am Rhein, wir möchten Euch herzlich zu unserem heutigen Heimspiel gegen Frankonia Rastatt hier im Sportpark am Oberwald begrüßen. Es steht mittlerweile das fünfte Heimspiel in dieser Saison an und unser Hygienekonzept für Besucher*innen und Aktive hat sich aus unserer Sicht bewährt. Der Erfolg ist aber nicht zuletzt darauf zurückzuführen, dass Ihr lieben Gäste, Euch vorbildlich mit den neuen Regeln arrangiert habt. Besonders die vielfache Nutzung der Onlineanmeldung über unsere Homepage www.svauamrhein.de hat den Verantwortlichen bei den Heimspielen die Arbeit erheblich erleichtert. Sportlich wollen wir heute nach der letzten Heimpleite wieder an die bisherigen Erfolge an heimischer Wirkungsstätte anknüpfen und mit Eurer Unterstützung die drei Punkte am Oberwald behalten. Ein besonderer Gruß geht wie immer an unsere heutigen Gäste aus Rastatt sowie dem Schiedsrichter der Partie. Aber nun freuen wir uns gemeinsam mit Euch auf ein spannendes Spiel. Wir wünschen allen einen sportlich fairen Verlauf und viel Freude an der „schönsten Nebensache der Welt“. Es grüßen Euch die Vorstände - Markus Ball und Sven Kreis! Hygienekonzept Sportpark am Oberwald Regeln für den Spielbetrieb ➢ Die Heimmannschaft muss spätestens 1,5 Std. vor Anpfiff auf dem Gelände sein, ➢ Die Gastmannschaft darf frühestens 1 Std. vor Anpfiff -

On the Origin and Composition of the German East-West Population Gap

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 12031 On the Origin and Composition of the German East-West Population Gap Christoph Eder Martin Halla DECEMBER 2018 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 12031 On the Origin and Composition of the German East-West Population Gap Christoph Eder Johannes Kepler University Linz Martin Halla Johannes Kepler University Linz, CD-Lab Aging, Health, and the Labor Market, IZA and Austrian Public Health Institute DECEMBER 2018 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 12031 DECEMBER 2018 ABSTRACT On the Origin and Composition of the German East-West Population Gap* The East-West gap in the German population is believed to originate from migrants escaping the socialist regime in the German Democratic Republic (GDR).