Tartuffe Education Pack

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monsieur De Pourceaugnac, Comédie-Ballet De Molière Et Lully

Monsieur de Pourceaugnac, comédie-ballet de Molière et Lully Dossier pédagogique Une production du Théâtre de l’Eventail en collaboration avec l’ensemble La Rêveuse Mise en scène : Raphaël de Angelis Direction musicale : Florence Bolton et Benjamin Perrot Chorégraphie : Namkyung Kim Théâtre de l’Eventail 108 rue de Bourgogne, 45000 Orléans Tél. : 09 81 16 781 19 [email protected] http://theatredeleventail.com/ Sommaire Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 2 La farce dans l’œuvre de Molière ................................................................................................ 3 Molière : éléments biographiques ............................................................................................. 3 Le comique de farce .................................................................................................................... 4 Les ressorts du comique dans Monsieur de Pourceaugnac .............................................. 5 Musique baroque et comédie-ballet ........................................................................................... 7 Qui est Jean-Baptiste Lully ? ........................................................................................................ 7 La musique dans Monsieur de Pourceaugnac ..................................................................... 8 La commedia dell’arte ................................................................................................................. -

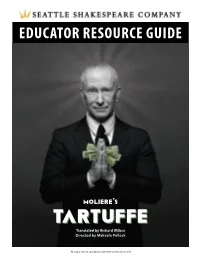

Translated by Richard Wilbur Directed by Makaela Pollock

Translated by Richard Wilbur Directed by Makaela Pollock All original material copyright © Seattle Shakespeare Company 2015 WELCOME Dear Educators, Tartuffe is a wonderful play, and can be great for students. Its major themes of hypocrisy and gullibility provide excellent prompts for good in-class discussions. Who are the “Tartuffes” in our 21st century world? What can you do to avoid being fooled the way Orgon was? Tartuffe also has some challenges that are best to discuss with students ahead of time. Its portrayal of religion as the source of Tartuffe’s hypocrisy angered priests and the deeply religious when it was first written, which led to the play being banned for years. For his part, Molière always said that the purpose of Tartuffe was not to lampoon religion, but to show how hypocrisy comes in many forms, and people should beware of religious hypocrisy among others. There is also a challenging scene between Tartuffe and Elmire at the climax of the play (and the end of Orgon’s acceptance of Tartuffe). When Tartuffe attempts to seduce Elmire, it is up to the director as to how far he gets in his amorous attempts, and in our production he gets pretty far! This can also provide an excellent opportunity to talk with students about staunch “family values” politicians who are revealed to have had affairs, the safety of women in today’s society, and even sexual assault, depending on the age of the students. Molière’s satire still rings true today, and shows how some societal problems have not been solved, but have simply evolved into today’s context. -

Download Teachers' Notes

Teachers’ Notes Researched and Compiled by Michele Chigwidden Teacher’s Notes Adelaide Festival Centre has contributed to the development and publication of these teachers’ notes through its education program, CentrED. Brink Productions’ by Molière A new adaptation by Paul Galloway Directed by Chris Drummond INTRODUCTION Le Malade imaginaire or The Hypochondriac by French playwright Molière, was written in 1673. Today Molière is considered one of the greatest masters of comedy in Western literature and his work influences comedians and dramatists the world over1. This play is set in the home of Argan, a wealthy hypochondriac, who is as obsessed with his bowel movements as he is with his mounting medical bills. Argan arranges for Angélique, his daughter, to marry his doctor’s nephew to get free medical care. The problem is that Angélique has fallen in love with someone else. Meanwhile Argan’s wife Béline (Angélique’s step mother) is after Argan’s money, while their maid Toinette is playing havoc with everyone’s plans in an effort to make it all right. Molière’s timeless satirical comedy lampoons the foibles of people who will do anything to escape their fear of mortality; the hysterical leaps of faith and self-delusion that, ironically, make us so susceptible to the quackery that remains apparent today. Brink’s adaptation, by Paul Galloway, makes Molière’s comedy even more accessible, and together with Chris Drummond’s direction, the brilliant ensemble cast and design team, creates a playful immediacy for contemporary audiences. These teachers’ notes will provide information on Brink Productions along with background notes on the creative team, cast and a synopsis of The Hypochondriac. -

Moliere Monsieur De Pourceaugnac

MOLIERE MONSIEUR DE POURCEAUGNAC « Il existe un jeu qui consiste à disposer sur quatre coins, quatre tonneaux et quatre planches bien amarrées, de monter sur ces planches, et à l’aide du corps, du souffle, de la voix, du visage et des mains, à recréer le monde…Alors il s’établit entre le spectateur et nous une circulation étroite, un échange d’âmes et de cœurs, une harmonisation du souffle de toutes les poitrines, qui nous redonnent du courage et raniment la foi que nous avons dans la vie… » J-L Barrault 1 2 Le Théâtre de l’éventail Fondée en 2006, la compagnie s’est efforcée de travailler La poésie est aussi un des axes de la compagnie. Cécile sur la tradition théâtrale, le théâtre populaire et Messineo mène ce travail à travers des lectures ou des l’itinérance. créations de spectacle, Persée et Andromède ou le plus Le premier spectacle, La Jalousie du Barbouillé et Le heureux des trois de Jules Laforgue (2011), L’homme aux Médecin volant, crée en 2007 a reçu le Prix Engagement semelles de vent sur l’oeuvre d’Arthur Rimbaud (2015). et Initiatives Jeunes dans l’Union Européenne. La seconde création, Le Médecin malgré lui (2011), a été jouée plus de 200 fois en salle ou en plein air, en France et à l’étranger (Espagne, Italie, Burkina Faso). Créé en 2014, Monsieur de Pourceaugnac, est la troisième pièce de Molière mise en scène par Raphaël de Angelis. Le spectacle sera recréé en 2016 dans sa version intégrale sous forme de « comédie-ballet » dans le cadre d’une collaboration avec l’ensemble de musique ancienne, La Rêveuse. -

1. Ouvrages Personnels 1. Théâtre Et Musique. Dramaturgie De L'insertion

OUVRAGES 1. Ouvrages personnels 1. Théâtre et musique. Dramaturgie de l’insertion musicale dans le théâtre français (1550-1680), Paris, Champion, 2002 2. L’« Enfance de la tragédie » (1610-1642). Pratiques tragiques françaises de Hardy à Corneille, Paris, PUPS, 2014 2. Direction d’ouvrages ou de numéros de revue 1. « Racine poète » (en collaboration avec D. Moncond’huy), La Licorne, n°50, 1999 2. Les Mises en scène de la parole aux XVIe et XVIIe siècles (en collaboration avec Gilles Siouffi), Montpellier, Presses Universitaires de la Méditerranée, 2007 3. Le Spectateur de théâtre à l’âge classique (XVIIe-XVIIIe siècles) (en collaboration avec Franck Salaün), Montpellier, L’Entretemps, 2008 4. Plus sur Rotrou : écrire le théâtre (en collaboration avec D. Moncond’huy), Paris, Atlande, 2008 5. « Le Théâtre de Jean Mairet », Littératures classiques, n°65, 2008 6. Les Sons du théâtre. Angleterre et France (XVIe-XVIIIe siècle). Éléments d’une histoire de l’écoute (co-direction Xavier Bisaro), Rennes, PUR, 2013 7. « Scènes de reconnaissance » (co-direction Franck Salaün et Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin), Arrêt sur scène / Scene Focus, n°2, 2013 (en ligne sur http://www.ircl.cnrs.fr) 8. « Préface et critique. Le paratexte théâtral en France, en Italie et en Espagne (XVIe-XVIIe siècles) » (co- direction Anne Cayuela, Françoise Decroisette et Marc Vuillermoz), Littératures classiques, n°83, 2014 9. « Français et langues de France dans le théâtre du XVIIe siècle », Littératures classiques, n°87, 2015 10. Les Théâtres anglais et français (XVIe-XVIIIe siècle). Contacts, circulation, influences (co-direction Florence March), Rennes, PUR, 2016 11. « Mettre en scène(s) L’École des femmes », (co-direction Jean-Noël Laurenti et Mickaël Bouffard), Arrêt sur scène / Scene Focus, n°5, 2016 12. -

Tartuffe, by Moliere, Translated by Richard Wilbur Presented by Perisphere Theater Resources for Teachers and Students

Tartuffe, by Moliere, translated by Richard Wilbur Presented by Perisphere Theater Resources for teachers and students January/February 2018 Created by Heather Benjamin and Bridget Grace Sheaff, 2017 Context for Tartuffe PLOT The story takes place in the home of the wealthy Orgon, where Tartuffe—a fraud and a pious imposter—has insinuated himself. He succeeds in winning the respect and devotion of the head of the house and then tries to marry his daughter, seduce his wife and scrounge the deed to the property. Tartuffe nearly gets away with it, but an emissary from King Louis XIV arrives in time to recover the property, free Monsieur Orgon and haul Tartuffe off to jail. His Frontispiece of the one of the earliest duplicity, lies, and overall trickery are finally exposed printings of Tartuffe, depicting the most and punished. famous scene, from a 1739 collected edition of his works in French and English, printed by John Watts. —Dramatists Play Service summary PLAY STYLE Molière’s dramatic roots lie in Old French farce, the unscripted popular plays that featured broad characters with robust attitudes and vulgar ways, emphasized a strong physical style of performance, and were an entertainment staple in the town marketplace and on the fairground. He was, likewise, greatly influenced by his interaction with the Italian commedia dell'arte performers who were known for both their improvisational skills and highly physical playing, and for the everyday truth they brought to their lively theatrical presentations. The “new brand” of French comedy, which Molière developed and perfected, featured the vivacity and physicality of farce, tempered by a commedia-inspired naturalness of character. -

Corneille in the Shadow of Molière Dominique Labbé

Corneille in the shadow of Molière Dominique Labbé To cite this version: Dominique Labbé. Corneille in the shadow of Molière. French Department Research Seminar, Apr 2004, Dublin, Ireland. halshs-00291041 HAL Id: halshs-00291041 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00291041 Submitted on 27 Nov 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. University of Dublin Trinity College French Department Research Seminar (6 April 2004) Corneille in the shadow of Molière Dominique Labbé [email protected] http://www.upmf-grenoble.fr/cerat/Recherche/PagesPerso/Labbe (Institut d'Etudes Politiques - BP 48 - F 38040 Grenoble Cedex) Où trouvera-t-on un poète qui ait possédé à la fois tant de grands talents (…) capable néanmoins de s'abaisser, quand il le veut, et de descendre jusqu'aux plus simples naïvetés du comique, où il est encore inimitable. (Racine, Eloge de Corneille) In December 2001, the Journal of Quantitative Linguistics published an article by Cyril Labbé and me (see bibliographical references at the end of this note, before appendixes). This article presented a new method for authorship attribution and gave the example of the main Molière plays which Pierre Corneille probably wrote (lists of these plays in appendix I, II and VI). -

Tartuffe Or the Hypocrite by Jean Baptiste Poquelin Moliere

Tartuffe or the Hypocrite by Jean Baptiste Poquelin Moliere Tartuffe or the Hypocrite by Jean Baptiste Poquelin Moliere Etext prepared by Dagny, [email protected] and John Bickers, [email protected] TARTUFFE OR THE HYPOCRITE by JEAN BAPTISTE POQUELIN MOLIERE Translated By Curtis Hidden Page INTRODUCTORY NOTE Jean Baptiste Poquelin, better known by his stage name of Moliere, stands without a rival at the head of French comedy. Born at Paris in January, 1622, where his father held a position in the royal household, he was educated at the Jesuit College de Clermont, and for some time studied law, which he soon abandoned for the stage. His life was spent in Paris and in the provinces, acting, directing page 1 / 151 performances, managing theaters, and writing plays. He had his share of applause from the king and from the public; but the satire in his comedies made him many enemies, and he was the object of the most venomous attacks and the most impossible slanders. Nor did he find much solace at home; for he married unfortunately, and the unhappiness that followed increased the bitterness that public hostility had brought into his life. On February 17, 1673, while acting in "La Malade Imaginaire," the last of his masterpieces, he was seized with illness and died a few hours later. The first of the greater works of Moliere was "Les Precieuses Ridicules," produced in 1659. In this brilliant piece Moliere lifted French comedy to a new level and gave it a new purpose--the satirizing of contemporary manners and affectations by frank portrayal and criticism. -

Monsieur DE Pourceaugnac MOLIERE

DOSSIER PEDAGOGIQUE Monsieur DE Pourceaugnac MOLIERE Marianne Wolfsohn Mise en scène Boris Bénézit / Antoine Laloux SOMMAIRE Musique / Arrangements Elodie Tellier Présentation Lumières / Régie Molière Sébastien Choriol Scénographie / Construction Monsieur DE Pourceaugnac Eve-Céline Leroux Le Théâtre de la Ramée Costumes / Décors La note d’intention La distribution AVEC Boris Bénézit Eraste Avant le spectacle p.x Emmanuel Bordier Une entrée par l’affiche p.x Sbrigani Une entrée par le décor et les Olivier Cariat Oronte costumes p.x Marie-Laure Desbordes Nérine Après le spectacle p.x Fred Egginton Revenir sur le spectacle p.x Le Médecin Rural – urbain p.x Morgane Grzegorski Julie L’étranger p.x Antoine Laloux L’Apothicaire Prolongements p.x Stéphane Piasentin Léonard de Pourceaugnac et Christophe Fouquet Héléna Lebesgue Durée : 1h45 Avec le soutien du Conseil Régional des Hauts de France Nord - Pas-de-Calais – Picardie, de la DRAC Nord-Pas-de-Calais-Picardie, de la Communauté de Communes de la Picardie Verte , du Théâtre du Beauvaisis, de la Comédie de Picardie, de la SPEDIDAM et du Conseil départemental de l’Oise Production Théâtre de la Ramée Molière Dramaturge et comédien français 1622 – 1673 Né à Paris, Jean-Baptiste Poquelin est le fils aîné d'un «valet de chambre et tapissier» du roi Louis XIII. Sa mère, qu’il perd lorsqu’il a dix ans était fille et petite fille fille de tapissier. La famille est aisée. Après avoir suivi un enseignement au collège de Clermont (futur lycée Louis-le-Grand), tenu par les Jésuites, il fait des études de droit à Orléans, puis accepte un temps la charge de «tapissier» pour Louis XIII. -

The Significance of Dorine in Revealing Moral Values In

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF DORINE IN REVEALING MORAL MESSAGES IN MOLIERE’S TARTUFFE AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By BONDAN ADHI WIBOWO Student Number: 024214040 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2008 i ii iii “Carpe diem, Seize the Day” iv This undergraduate thesis is dedicated to My Beloved Family, My Friends, And those who love me v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The first and foremost, I would like to bestow my deepest gratitude to Jesus Christ for giving me his blessing, strength, chance, and patience. Thanks for always guiding me every second in my life. Secondly, my greatest appreciation goes to my beloved parents, Heru Pramono and Pudjiningtyas, who always give me love, encouragement, and motivation to finish my study. I thank my brother Ivan Adi Prabowo for his love and support in many ways. My gratitude is also for my big family, I thank them. A special thank for my advisor, Maria Ananta Tri Suryandari, S.S., M.Ed., who has always give me her precious time in guiding me to finish this thesis. I thank her for correcting my thesis so that I could complete this thesis. Big thanks, for helping me to realize my ideas. I also would like to thank to my Co. advisor, Paulus Sarwoto, S.S., M.A for his suggestions and ideas. I thank to all lecture in Sanata Dharma University for teaching me many things. My gratitude also goes to all my best friends; Yabes, Sigit Nugraha, Fitra, Leo, David, Dimas, D N G, Yere, Jeff, Maynard, Koh Abun, Garry, Alfa, Parjo, Steva, Wawik. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Peter Blair, Executive Director December 6, 2011 [email protected]

BoHo Theatre P.O. Box 409267, Chicago, IL 60640 773-791-2393 www.BoHoTheatre.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Peter Blair, Executive Director December 6, 2011 [email protected] BOHO THEATRE TAKES A FRESH LOOK AT A CLASSIC SATIRE WITH THEIR STEAMPUNK TARTUFFE CHICAGO—BoHo Theatre brings laughs and style to the stage this January with Ranjit Bolt’s contemporary translation of Molière’s Tartuffe, the classic tale of sex, money, and the power of persuasion. Tartuffe runs January 13th through February 12th, 2012, at Theater Wit, 1229 W. Belmont Avenue, and is directed by BoHo’s Associate Artistic Director Peter Robel. By using the anachronistic mashup genre called steampunk, director Robel seeks to highlight the machinations of the wicked Tartuffe as he uses one man’s fear of change to his advantage, a fear all too familiar today. In the midst of societal upheaval, when the lines between church and state are being drawn between those for whom religion is the bedrock of society and a younger generation eager to accept change, comes the charlatan Tartuffe. Masquerading as a man of God, Tartuffe worms his way into the life of pious family patriarch Orgon and is soon trying to make off with the man’s wealth, his daughter, and even his wife! Though the rest of the family goes to hilarious lengths to show Orgon the error of his ways and expel Tartuffe from their home, the con man always seems to be one step ahead of them. By using steampunk (a scifi subgenre that mixes Victorian history and aesthetic with futuristic steam-powered technology) as a backdrop, BoHo’s production mirrors the tumultuous societal landscape of 17th century France as a world that at once seems both familiar and alien, when old and new exist side by side. -

THE IMAGINARY INVALID ADAPTED by CONSTANCE CONGDON BASED on a NEW TRANSLATION by DAN SMITH TABLE of CONTENTS the Imaginary Invalid Character List

AUDIENCE GUIDE MOLIÈRE’S THE IMAGINARY INVALID ADAPTED BY CONSTANCE CONGDON BASED ON A NEW TRANSLATION BY DAN SMITH TABLE OF CONTENTS The Imaginary Invalid Character List .................................. 3 Synopsis ........................................................ 4 Playwright Biography: Molière ....................................... 5 Molière Timeline .................................................. 6 Translator and Adaptor Biographies .................................. 7 Translation and Adaptation in The Imaginary Invalid ..................... 8 Themes ......................................................... 9 Quackery and Medicine in 17th Century France ...................... 10 How To Become A Doctor ....................................... 11 Resources & Further Reading ................................... 12 A NOISE WITHIN’S EDUCATION PROGRAMS MADE POSSIBLE IN PART BY: The Ahmanson Foundation, AMC, The Capital Group Companies Charitable Foundation, The Michael J. Connell Foundation, The Dick and Sally Roberts Coyote Foundation, The Dwight Stuart Youth Fund, Edison International, The Green Foundation, The Michael & Irene Ross Endowment Fund of the Jewish Community Foundation of Los Angeles, Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, Metropolitan Associates, National Endowment for the Arts: Shakespeare in American Communities, The Kenneth T. & Eileen L. Norris Foundation, The Ralph M. Parsons Foundation, Pasadena Rotary Club, The Ann Peppers Foundation, The Rose Hills Foundation,