Tartuffe: a Modern Adaptation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

A Dangerous Method

A David Cronenberg Film A DANGEROUS METHOD Starring Keira Knightley Viggo Mortensen Michael Fassbender Sarah Gadon and Vincent Cassel Directed by David Cronenberg Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Official Selection 2011 Venice Film Festival 2011 Toronto International Film Festival, Gala Presentation 2011 New York Film Festival, Gala Presentation www.adangerousmethodfilm.com 99min | Rated R | Release Date (NY & LA): 11/23/11 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Donna Daniels PR Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Donna Daniels Ziggy Kozlowski Carmelo Pirrone 77 Park Ave, #12A Jennifer Malone Lindsay Macik New York, NY 10016 Rebecca Fisher 550 Madison Ave 347-254-7054, ext 101 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 New York, NY 10022 Los Angeles, CA 90036 212-833-8833 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8844 fax 323-634-7030 fax A DANGEROUS METHOD Directed by David Cronenberg Produced by Jeremy Thomas Co-Produced by Marco Mehlitz Martin Katz Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Executive Producers Thomas Sterchi Matthias Zimmermann Karl Spoerri Stephan Mallmann Peter Watson Associate Producer Richard Mansell Tiana Alexandra-Silliphant Director of Photography Peter Suschitzky, ASC Edited by Ronald Sanders, CCE, ACE Production Designer James McAteer Costume Designer Denise Cronenberg Music Composed and Adapted by Howard Shore Supervising Sound Editors Wayne Griffin Michael O’Farrell Casting by Deirdre Bowen 2 CAST Sabina Spielrein Keira Knightley Sigmund Freud Viggo Mortensen Carl Jung Michael Fassbender Otto Gross Vincent Cassel Emma Jung Sarah Gadon Professor Eugen Bleuler André M. -

New Age, Vol. 18, No. 19, Mar. 9, 1016

NOTES OF THEWEEK . VICTORIA. By Alice Morning . FOREIGNAFFAIRS. By S. Verdad. Views AND REVIEWS : COLLECTIVEPSYCHOLOGY. UNEDITEDOPINIONS : THE CASE FOR GERMANY . By A. E. R. REVIEWS : YOUTH : A PLAY. By Miles Malleson. A PATHOLOGICALVIEW OF THE UNITEDSTATES-I. By E. A. B. THE RUSSIAN CAMPAIGN. By Stanley Washburn . LITTLEEPISTLES-I : To SIR OLIVER LODGE. BY National Guildsman . PASTICHE. By C. E. B., Ruth Pitter, W. Mears, P. Selver . MORE LETTERS TO My NEPHEW. By Anthony Farley . LETTERS TO THE EDITOR from C. S. M., Ernest Kempston, Oscar Levy, A. H. Murray, DRAMA. By John Francis Hope. Sheikh M. H. Kedwai of Gadia, B., BOUDOIR ECONOMY: A DUOLOGUE. By D. Leigh C. E. M. J., M. Bridges Adams, Claude Bennett . Askew, Alfred Willams, Huntly Carter, A. READERS ANDWRITERS. By R. H. C. Hanson . MAN AND MANNERS: AN OCCASIONALDIARY. PRESS CUTTINGS. that it is not only just that our wealthy men should NOTES OF THE WEEK pay for the war in actual loss of their capital, but, sooner or later, it will be necessary. Its justice may THOUGH no one would guess it who has the acquaintance be seen from the following considerations. In the first of daily journalists, and though, it must be said, place, it has always been the defence of private wealth they are modestly sceptical of it themselves, the power (maintained, be it remembered, by the whole constitutional of daily journalism is enormous. By its means authority) that its accumulation in this form (consistinglargely of repetition), not only are lies and half- ensured the nation an ample reserve for precisely such an truths concerning public affairs put and kept in emergency as a great war. -

Cornell Alumni News Volume 51, Number 17 June 1, 1949 Price 25 Cents

Cornell Alumni News Volume 51, Number 17 June 1, 1949 Price 25 Cents FicMϊn Fall|Creek Gorge in June NEW BOOKS BY CORNELLIANS Dirt Roads to Stoneposts-έ)/ Romeyn Berry '04 loo pages, 6 x 9, $2. postpaid OMEYN BERRY, for twenty-five years an incisive interpreter R of Cornell in this paper, here records his observations of farming for profit at Stoneposts, his rural estate in Tompkins County. The man can, and does, drive a manure-spreader with dignity and plow a straight furrow without missing a wild goose, a meadow-lark, or a white cloud in the skies above him. Readers of "Now In My Time!" will find in DIRT ROADS TO STONE- POSTS a collection of Mr. Berry's more noteworthy contributions to other publications (with some new ones appearing here for the first time) which Morris Bishop, in his Introduction, pronounces "pure gems." It's the smell of the land! It's Rym! It's the spirit of the hills that lie near enough to hear the Bells of Cornell! The Merry Old Mobίles~by Larry Freeman, PhD 2.50 pages, 6 x 9, $5 postpaid ERE is a book that takes you miles away from today's stream- H lined necessity, back to the time when all men were assumed to be master roadside mechanics and all women too delicate to drive. Fifty fabulous years have passed since the advent of the automobile. Quite fittingly, the changes it has wrought in the American Scene are portrayed by one of the country's leading psychologists and col- lectors. -

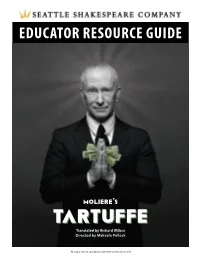

Translated by Richard Wilbur Directed by Makaela Pollock

Translated by Richard Wilbur Directed by Makaela Pollock All original material copyright © Seattle Shakespeare Company 2015 WELCOME Dear Educators, Tartuffe is a wonderful play, and can be great for students. Its major themes of hypocrisy and gullibility provide excellent prompts for good in-class discussions. Who are the “Tartuffes” in our 21st century world? What can you do to avoid being fooled the way Orgon was? Tartuffe also has some challenges that are best to discuss with students ahead of time. Its portrayal of religion as the source of Tartuffe’s hypocrisy angered priests and the deeply religious when it was first written, which led to the play being banned for years. For his part, Molière always said that the purpose of Tartuffe was not to lampoon religion, but to show how hypocrisy comes in many forms, and people should beware of religious hypocrisy among others. There is also a challenging scene between Tartuffe and Elmire at the climax of the play (and the end of Orgon’s acceptance of Tartuffe). When Tartuffe attempts to seduce Elmire, it is up to the director as to how far he gets in his amorous attempts, and in our production he gets pretty far! This can also provide an excellent opportunity to talk with students about staunch “family values” politicians who are revealed to have had affairs, the safety of women in today’s society, and even sexual assault, depending on the age of the students. Molière’s satire still rings true today, and shows how some societal problems have not been solved, but have simply evolved into today’s context. -

Download Teachers' Notes

Teachers’ Notes Researched and Compiled by Michele Chigwidden Teacher’s Notes Adelaide Festival Centre has contributed to the development and publication of these teachers’ notes through its education program, CentrED. Brink Productions’ by Molière A new adaptation by Paul Galloway Directed by Chris Drummond INTRODUCTION Le Malade imaginaire or The Hypochondriac by French playwright Molière, was written in 1673. Today Molière is considered one of the greatest masters of comedy in Western literature and his work influences comedians and dramatists the world over1. This play is set in the home of Argan, a wealthy hypochondriac, who is as obsessed with his bowel movements as he is with his mounting medical bills. Argan arranges for Angélique, his daughter, to marry his doctor’s nephew to get free medical care. The problem is that Angélique has fallen in love with someone else. Meanwhile Argan’s wife Béline (Angélique’s step mother) is after Argan’s money, while their maid Toinette is playing havoc with everyone’s plans in an effort to make it all right. Molière’s timeless satirical comedy lampoons the foibles of people who will do anything to escape their fear of mortality; the hysterical leaps of faith and self-delusion that, ironically, make us so susceptible to the quackery that remains apparent today. Brink’s adaptation, by Paul Galloway, makes Molière’s comedy even more accessible, and together with Chris Drummond’s direction, the brilliant ensemble cast and design team, creates a playful immediacy for contemporary audiences. These teachers’ notes will provide information on Brink Productions along with background notes on the creative team, cast and a synopsis of The Hypochondriac. -

Print Journalism: a Critical Introduction

Print Journalism A critical introduction Print Journalism: A critical introduction provides a unique and thorough insight into the skills required to work within the newspaper, magazine and online journalism industries. Among the many highlighted are: sourcing the news interviewing sub-editing feature writing and editing reviewing designing pages pitching features In addition, separate chapters focus on ethics, reporting courts, covering politics and copyright whilst others look at the history of newspapers and magazines, the structure of the UK print industry (including its financial organisation) and the development of journalism education in the UK, helping to place the coverage of skills within a broader, critical context. All contributors are experienced practising journalists as well as journalism educators from a broad range of UK universities. Contributors: Rod Allen, Peter Cole, Martin Conboy, Chris Frost, Tony Harcup, Tim Holmes, Susan Jones, Richard Keeble, Sarah Niblock, Richard Orange, Iain Stevenson, Neil Thurman, Jane Taylor and Sharon Wheeler. Richard Keeble is Professor of Journalism at Lincoln University and former director of undergraduate studies in the Journalism Department at City University, London. He is the author of Ethics for Journalists (2001) and The Newspapers Handbook, now in its fourth edition (2005). Print Journalism A critical introduction Edited by Richard Keeble First published 2005 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX9 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” Selection and editorial matter © 2005 Richard Keeble; individual chapters © 2005 the contributors All rights reserved. -

Through FILMS 70 Years of European History Through Films Is a Product in Erasmus+ Project „70 Years of European History 1945-2015”

through FILMS 70 years of European History through films is a product in Erasmus+ project „70 years of European History 1945-2015”. It was prepared by the teachers and students involved in the project – from: Greece, Czech Republic, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Turkey. It’ll be a teaching aid and the source of information about the recent European history. A DANGEROUS METHOD (2011) Director: David Cronenberg Writers: Christopher Hampton, Christopher Hampton Stars: Michael Fassbender, Keira Knightley, Viggo Mortensen Country: UK | GE | Canada | CH Genres: Biography | Drama | Romance | Thriller Trailer In the early twentieth century, Zurich-based Carl Jung is a follower in the new theories of psychoanalysis of Vienna-based Sigmund Freud, who states that all psychological problems are rooted in sex. Jung uses those theories for the first time as part of his treatment of Sabina Spielrein, a young Russian woman bro- ught to his care. She is obviously troubled despite her assertions that she is not crazy. Jung is able to uncover the reasons for Sa- bina’s psychological problems, she who is an aspiring physician herself. In this latter role, Jung employs her to work in his own research, which often includes him and his wife Emma as test subjects. Jung is eventually able to meet Freud himself, they, ba- sed on their enthusiasm, who develop a friendship driven by the- ir lengthy philosophical discussions on psychoanalysis. Actions by Jung based on his discussions with another patient, a fellow psychoanalyst named Otto Gross, lead to fundamental chan- ges in Jung’s relationships with Freud, Sabina and Emma. -

Wmc Investigation: 10-Year Analysis of Gender & Oscar

WMC INVESTIGATION: 10-YEAR ANALYSIS OF GENDER & OSCAR NOMINATIONS womensmediacenter.com @womensmediacntr WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER ABOUT THE WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER In 2005, Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan, and Gloria Steinem founded the Women’s Media Center (WMC), a progressive, nonpartisan, nonproft organization endeav- oring to raise the visibility, viability, and decision-making power of women and girls in media and thereby ensuring that their stories get told and their voices are heard. To reach those necessary goals, we strategically use an array of interconnected channels and platforms to transform not only the media landscape but also a cul- ture in which women’s and girls’ voices, stories, experiences, and images are nei- ther suffciently amplifed nor placed on par with the voices, stories, experiences, and images of men and boys. Our strategic tools include monitoring the media; commissioning and conducting research; and undertaking other special initiatives to spotlight gender and racial bias in news coverage, entertainment flm and television, social media, and other key sectors. Our publications include the book “Unspinning the Spin: The Women’s Media Center Guide to Fair and Accurate Language”; “The Women’s Media Center’s Media Guide to Gender Neutral Coverage of Women Candidates + Politicians”; “The Women’s Media Center Media Guide to Covering Reproductive Issues”; “WMC Media Watch: The Gender Gap in Coverage of Reproductive Issues”; “Writing Rape: How U.S. Media Cover Campus Rape and Sexual Assault”; “WMC Investigation: 10-Year Review of Gender & Emmy Nominations”; and the Women’s Media Center’s annual WMC Status of Women in the U.S. -

The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter Edited by Peter Raby Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521651239 - The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter Edited by Peter Raby Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter provides an introduction to one of the world’s leading and most controversial writers, whose output in many genres and roles continues to grow. Harold Pinter has written for the theatre, radio, television and screen, in addition to being a highly successful director and actor. This volume examines the wide range of Pinter’s work (including his recent play Celebration). The first section of essays places his writing within the critical and theatrical context of his time, and its reception worldwide. The Companion moves on to explore issues of performance, with essays by practi- tioners and writers. The third section addresses wider themes, including Pinter as celebrity, the playwright and his critics, and the political dimensions of his work. The volume offers photographs from key productions, a chronology and bibliography. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521651239 - The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter Edited by Peter Raby Frontmatter More information CAMBRIDGE COMPANIONS TO LITERATURE The Cambridge Companion to Greek Tragedy The Cambridge Companion to the French edited by P. E. Easterling Novel: from 1800 to the Present The Cambridge Companion to Old English edited by Timothy Unwin Literature The Cambridge Companion to Modernism edited by Malcolm Godden and Michael edited by Michael Levenson Lapidge The Cambridge Companion to Australian The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Literature Romance edited by Elizabeth Webby edited by Roberta L. Kreuger The Cambridge Companion to American The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Women Playwrights English Theatre edited by Brenda Murphy edited by Richard Beadle The Cambridge Companion to Modern British The Cambridge Companion to English Women Playwrights Renaissance Drama edited by Elaine Aston and Janelle Reinelt edited by A. -

Natural Pursuits – the Screen Dramas of Simon Gray Television Season at BFI Southbank in August 2011

PRESS RELEASE June 2011 11/49 Natural Pursuits – The Screen Dramas of Simon Gray Television Season at BFI Southbank in August 2011 BFI Southbank celebrates the tragi-comic screen dramas of the late Simon Gray. A writer of immense wit and intellectual charm whose razor-sharp dialogue is unsurpassed. The month long season features some of Gray’s most celebrated work including screenings of Unnatural Pursuits (1992), After Pilkington (1987) and They Never Slept (1991) which feature performances by British acting elite including Alan Bates, Edward Fox and Miranda Richardson. Following the screening of They Never Slept, a panel of guests including producer Kenith Trodd, and directors Udayan Prasad and Christopher Morahan will discuss his great contribution to television drama and the theatre illustrated with clips of some of his early and rare television plays to be chaired by Broadcaster Matthew Sweet. After the screening of Butley on Sunday 14 Aug, Lindsay Posner, director of the 40th anniversary revival of the play currently running at the Duchess Theatre will also be welcomed to the BFI stage for a Q&A. Gray wrote prolifically from the mid-60s onwards for both the West End stage (Otherwise Engaged, Quartermaine’s Terms, The Late Middle Classes, Butley) and for television, where such important early successes such as Death of a Teddy Bear, Man in a Sidecar and The Caramel Crisis were carelessly wiped. His most fertile period writing specifically for TV occurred between 1975 and 1993 during a close collaboration with producer Kenith Trodd and four major directors, Michael Lindsay- Hogg, Christopher Morahan, Udayan Prasad and Pat O’Connor. -

World Notions Disorderly

Quixote and the Logic of Exceptionalism Quixote Aaron R. Hanlon Aaron A WORLDof DISORDERLY NOTIONS A WORLD OF DISORDERLY NOTIONS A WORLD Y of DISORDERL NOTIONS h Quixote and the Logic of Exceptionalism Aaron R. Hanlon university of virginia press Charlottesville and London University of Virginia Press © 2019 by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper First published 2019 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Hanlon, Aaron R. (Aaron Raymond), 1982– author. Title: A world of disorderly notions : Quixote and the logic of exceptionalism / Aaron R. Hanlon. Description: Charlottesville : University of Virginia Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018044533 | ISBN 9780813942162 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780813942179 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: English fiction—18th century—History and criticism—Theory, etc. | Characters and characteristics in literature | American fiction—19th century—History and criticism—Theory, etc. | Exceptionalism in literature. | Cervantes Saavedra, Miguel de, 1547–1616. Don Quixote. | English fiction—Spanish influences. | American fiction—Spanish influences. Classification: LCC PR858.C47 H36 2019 | DDC 823/.50927—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018044533 Cover art: From vol. 1 of Don Quixote, Miguel de Cervantes (London: Cadell & Davies, 1818). Proof with etched letters, print by Francis Engleheart, after Robert Smirke. (Image © Trustees of the British Museum) For Nhi, crosser of boisterous oceans A world of disorderly notions, picked out of his books, crowded into his imagination. —Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quixote CONTENTS Introduction: Tilting at Concepts 1 Part I: The Character of Quixotism 1.