THE SPLIT NOUN PHRASE in CLASSICAL LATIN by Zachary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Copyright, I Ilir Bejtja 2014

Copyright, i Ilir Bejtja 2014 1 Udhёheqёsi i Ilir Bejtja, vёrteton se ky ёshtё version i miratuar i disertacionit tё mёposhtёm: The supervisor of Ilir Bejtja certifies that this is the approved version of the below dissertation: MARKETINGU SELEKTIV PER KËRKESË TURISTIKE SELEKTIVE PËR HAPËSIRA TURISTIKE TË PANDOTURA Prof. Dr. Bardhyl Ceku 2 MARKETINGU SELEKTIV PËR KËRKESË TURISTIKE SELEKTIVE PËR HAPËSIRA TURISTIKE TË PANDOTURA Pregatitur nga: Ilir Bejtja “Disertacioni i paraqitur nё Fakultetin e Biznesit Universiteti “Aleksandёr Moisu” Durrёs Nё pёrputhje tё plotё Me kёrkesat Pёr gradёn “Doktor” Universiteti “Aleksandёr Moisu” Durrёs Dhjetor, 2014 3 DEDIKIM Ky disertacion i dedikohet familjes time, nënës dhe motrës time, për pritëshmëritë e tyre të vazhdueshme dhe besimin që kanë tek unë. 4 MIRËNJOHJE Një mirënjohje të veçantë për të gjithë ata që më kanë ndihmuar të pasuroj idetë e mia lidhur me zhvillimin e turizmit të qëndrueshëm, profesionistë nësektor, bashkëpunëtorë dhe profesorë, si edhe njerëz të mi të afërt e të dashur për mështetjen dhe nxitjen e tyre të vazhdueshme që unë të arrija të përfundoja këtë disertacion! Faleminderit të gjithëve! 5 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my family, my mother and my sister for their continuous expectancy and confidence on me. 6 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A special thank to all of them who helped me to enrich my ideas on the sustainable tourism development so far, sector professionals, collaborators and teachers, and to my loved people as well for their continuous support and incitement to commit with the completion of this dissertation! Thank you all! 7 Deklaratё mbi origjinalitetin Ilir Bejtja Deklaroj se kjo tezë përfaqëson punën time origjinale dhe nuk kam përdorur burime të tjera, përveç atyre të shkruajtura nëpërmjet citimeve. -

PAUL at ILLYRICUM, TITUS to DALMATIA: EARLY CHRISTIANITY in the ROMAN ADRIATIC ALBANIA • MONTENEGRO • CROATIA September 20 - October 1, 2020 Tour Host: Dr

Tutku Travel Programs Endorsed by Biblical Archaeology Society PAUL AT ILLYRICUM, TITUS TO DALMATIA: EARLY CHRISTIANITY IN THE ROMAN ADRIATIC ALBANIA • MONTENEGRO • CROATIA September 20 - October 1, 2020 Tour Host: Dr. Mark Wilson organized by Paul at Illyricum, Titus to Dalmatia: Early Christianity in the Roman Adriatic / September 21-October 1, 2020 Dyrrachium Paul at Illyricum, Titus to Dalmatia: Early Christianity in the Roman Adriatic Mark Wilson, D.Litt. et Phil., Director, Asia Minor Research Center, Antalya, Turkey; Associate Professor Extraordinary of New Testament, Stellenbosch University [email protected] Twice in his letters Paul mentions Christian activity in the Adriatic – Sep 24 Thu Kotor Illyricum (Romans 15:19) and Dalmatia (2 Timothy 4:10). Both were We will cross the border into Montenegro to visit the Roman bridge Roman provinces now located in Albania, Montenegro, and Croatia. We (Adzi-Pasa) at Podgorica; then we’ll visit the Roman site of Budva with will visit numerous Roman sites in these countries as we seek to discover its baths and necropolis; in the afternoon we will tour the old town and early Christian traditions. These traditions are kept alive through the castle at the UNESCO world heritage site of Kotor. Dinner and overnight architecture of majestic Byzantine churches. Several UNESCO World in Kotor. (B, D) Heritage sites await us as we reach them through spectacular natural Sep 25 Fri Dubrovnik scenery. Discover this little-known biblical world as we travel the Diocletian’s Palace, eastern Adriatic together in 2020. Split We will cross the border into Croatia and visit historic Dubrovnik, another UNESCO site and take a Apollonia walking tour of its city walls and old town, Franciscan church and monastery and have free time for a cable car ride with a panoramic overlook. -

Conference Proceedings

1st International Conference on Cultural Heritage, Media and Tourism Прва меѓународна конференција за културно наследство, медиуми и туризам Conference Proceedings Ohrid, Macedonia 18-19.01.2013 Organizers: Institute for Socio-cultural Anthropology of Macedonia University for Audio-Visual Arts, ESRA- Skopje, Paris, New York Euro-Asian Academy for Television and Radio, Moscow, Russia Program Committee: Rubin Zemon, Ph.D. (University St. Paul the Apostle), Ohrid, Macedonia Lina Gergova, Ph.D. (Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Studies with Ethnographic Museum) Sofia, Bulgaria Yasar Tonta, Ph.D. (Hacettepe University) Ankara, Turkey Armanda Kodra Hysa, Ph.D. (University College London, School of Slavonic and East European Studies) London, UK) Lidija Vujacic, Ph.D. (University of Monte Negro) Niksic, Monte Negro Dimitar Dymitrov, Ph.D. (Academy of Film, Television and Internet Communication) Sofia, Bulgaria Gabriela Rakicevic, Ph.D. (Faculty of Tourism and Hospitality)Ohrid, Macedonia Misho Netkovski, Ph.D. (University for Audio- Visual Arts/ ESRA) Skopje, Macedonia Organization Committee: Rubin Zemon, Ph.D. (University St. Paul the Apostle), Ohrid, Macedonia Verica Dzijanoska, (Institute for Socio-Cultural Anthropology of Macedonia) Samoil Malcheski, Ph.D. (University St. Paul the Apostle), Ohrid, Macedonia Jane Bakreski, Ph.D. (University St. Paul the Apostle), Ohrid, Macedonia Dijana Capeska-Bogatinoska, M.Sc. (University St. Paul the Apostle), Ohrid, Macedonia Lina Miloshevska-lecturer (University -

Dokumenti I Strategjisë Së Zhvillimit Të Territorit Të Bashkisë Elbasan

BASHKIA ELBASAN DREJTORIA E PLANIFIKIMIT TË TERRITORIT Adresa: Bashkia Elbasan, Rr. “Q. Stafa”, Tel.+355 54 400152, e-mail: [email protected], web: www.elbasani.gov.al DOKUMENTI I STRATEGJISË SË ZHVILLIMIT TË TERRITORIT TË BASHKISË ELBASAN MIRATOHET KRYETARI I K.K.T Z. EDI RAMA MINISTRIA E ZHVILLIMIT URBAN Znj. EGLANTINA GJERMENI KRYETARI I KËSHILLIT TË BASHKISË Z. ALTIN IDRIZI KRYETARI I BASHKISË Z. QAZIM SEJDINI Miratuar me Vendim të Këshillit të Bashkisë Elbasan Nr. ___Datë____________ Miratuar me Vendim të Këshillit Kombëtar të Territorit Nr. 1 Datë 29/12/2016 Përgatiti Bashkia Elbasan Mbështeti Projekti i USAID për Planifikimin dhe Qeverisjen Vendore dhe Co-PLAN, Instituti për Zhvillimin e Habitatit 1 TABELA E PËRMBAJTJES AUTORËSIA DHE KONTRIBUTET ........................................................................................ 6 SHËNIM I RËNDËSISHËM ....................................................................................................... 7 I. SFIDAT E BASHKISË ELBASAN ....................................................................................... 11 1.1 Tendencat kryesore të zhvillimit të pas viteve `90të ......................................................................................... 13 1.1.1 Policentrizmi ............................................................................................................................................. 15 1.2 Territori dhe mjedisi ........................................................................................................................................ -

Characters for Classical Latin

Characters for Classical Latin David J. Perry version 13, 2 July 2020 Introduction The purpose of this document is to identify all characters of interest to those who work with Classical Latin, no matter how rare. Epigraphers will want many of these, but I want to collect any character that is needed in any context. Those that are already available in Unicode will be so identified; those that may be available can be debated; and those that are clearly absent and should be proposed can be proposed; and those that are so rare as to be unencodable will be known. If you have any suggestions for additional characters or reactions to the suggestions made here, please email me at [email protected] . No matter how rare, let’s get all possible characters on this list. Version 6 of this document has been updated to reflect the many characters of interest to Latinists encoded as of Unicode version 13.0. Characters are indicated by their Unicode value, a hexadecimal number, and their name printed IN SMALL CAPITALS. Unicode values may be preceded by U+ to set them off from surrounding text. Combining diacritics are printed over a dotted cir- cle ◌ to show that they are intended to be used over a base character. For more basic information about Unicode, see the website of The Unicode Consortium, http://www.unicode.org/ or my book cited below. Please note that abbreviations constructed with lines above or through existing let- ters are not considered separate characters except in unusual circumstances, nor are the space-saving ligatures found in Latin inscriptions unless they have a unique grammatical or phonemic function (which they normally don’t). -

On the Roman Frontier1

Rome and the Worlds Beyond Its Frontiers Impact of Empire Roman Empire, c. 200 B.C.–A.D. 476 Edited by Olivier Hekster (Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands) Editorial Board Lukas de Blois Angelos Chaniotis Ségolène Demougin Olivier Hekster Gerda de Kleijn Luuk de Ligt Elio Lo Cascio Michael Peachin John Rich Christian Witschel VOLUME 21 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/imem Rome and the Worlds Beyond Its Frontiers Edited by Daniëlle Slootjes and Michael Peachin LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016036673 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 1572-0500 isbn 978-90-04-32561-6 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-32675-0 (e-book) Copyright 2016 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi and Hotei Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

The Jesuit College of Asunción and the Real Colegio Seminario De San Carlos (C

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/91085 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications The Uses of Classical Learning in the Río de la Plata, c. 1750-1815 by Desiree Arbo A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics and Ancient History University of Warwick, Department of Classics and Ancient History September 2016 ii Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES ...........................................................................................................V LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................V ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................. VI DECLARATION AND INCLUSION OF MATERIAL FROM A PREVIOUS PUBLICATION ............................................................................................................ VII NOTE ON REFERENCES ........................................................................................... VII ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................. -

Albanien 2014

Albanien 2014 Inhalt Ziel dieser Kulturreise, verfasst von Helmut Kapl ............................................................................... 1 Besa, der Schlüssel zur Eigenstaatlichkeit ........................................................................................... 3 Kloster Sveti Naum, Geschenk an Jugoslawien ................................................................................... 4 Französisches Protektorat Korca ......................................................................................................... 6 Mercedesvorliebe Albaniens und Kamenica ....................................................................................... 7 Kirchen von Mborje, Boboshtice und Voskopoja ................................................................................ 8 Fresken von Onufi in Shelcan mit Astronauten ................................................................................... 9 Kirche und Moschee in Elbasan ........................................................................................................ 10 Römische Pferderelaisstation Ad Quintum ....................................................................................... 10 Onufri-Museum in der Festung von Berat ........................................................................................ 11 Tekke der Bektaschi und Junggesellenmosche in Berat .................................................................... 11 Klosteranlage in Ardenica ................................................................................................................ -

Res Publica and

Durham E-Theses 'Without Body or Form': Res Publica and the Roman Republic HODGSON, LOUISE,LOVELACE How to cite: HODGSON, LOUISE,LOVELACE (2013) 'Without Body or Form': Res Publica and the Roman Republic, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/8506/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk DURHAM UNIVERSITY ‘Without Body or Form’ Res Publica and the Roman Republic LOUISE LOVELACE HODGSON 2013 A thesis submitted to the Department of Classics and Ancient History of Durham University in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the author's prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .............................................................................................................................. -

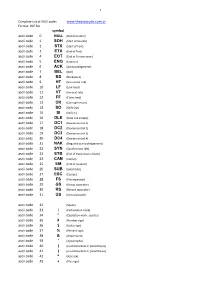

Symbol BS HT LF VT FF CR SO SI EM FS GS RS US ! " # $ % & ' ( )

³ Complete List of ASCii codes www.theasciicode.com.ar Format: PDF file symbol ascii code 0 NULL (Null character) ascii code 1 SOH (Start of Header) ascii code 2 STX (Start of Text) ascii code 3 ETX (End of Text) ascii code 4 EOT (End of Transmission) ascii code 5 ENQ (Enquiry) ascii code 6 ACK (Acknowledgement) ascii code 7 BEL (Bell) ascii code 8 BS (Backspace) ascii code 9 HT (Horizontal Tab) ascii code 10 LF (Line feed) ascii code 11 VT (Vertical Tab) ascii code 12 FF (Form feed) ascii code 13 CR (Carriage return) ascii code 14 SO (Shift Out) ascii code 15 SI (Shift In) ascii code 16 DLE (Data link escape) ascii code 17 DC1 (Device control 1) ascii code 18 DC2 (Device control 2) ascii code 19 DC3 (Device control 3) ascii code 20 DC4 (Device control 4) ascii code 21 NAK (Negative acknowledgement) ascii code 22 SYN (Synchronous idle) ascii code 23 ETB (End of transmission block) ascii code 24 CAN (Cancel) ascii code 25 EM (End of medium) ascii code 26 SUB (Substitute) ascii code 27 ESC (Escape) ascii code 28 FS (File separator) ascii code 29 GS (Group separator) ascii code 30 RS (Record separator) ascii code 31 US (Unit separator) ascii code 32 (Space) ascii code 33 ! (Exclamation mark) ascii code 34 " (Quotation mark ; quotes) ascii code 35 # (Number sign) ascii code 36 $ (Dollar sign) ascii code 37 % (Percent sign) ascii code 38 & (Ampersand) ascii code 39 ' (Apostrophe) ascii code 40 ( (round brackets or parentheses) ascii code 41 ) (round brackets or parentheses) ascii code 42 * (Asterisk) ascii code 43 + (Plus sign) ³ ascii code 44 , (Comma) ascii code 45 - (Hyphen) ascii code 46 . -

The Bank of America Celebrated National Punctuation Day with Week-Long Celebrations and Trivia Contests in 2005 and 2006

The Bank of America celebrated National Punctuation Day with week-long celebrations and trivia contests in 2005 and 2006 Hi Jeff! We are excited about celebrating National Punctuation Day soon! Here is the document for our 2006 National Punctuation Day Contest. It is divided into pages — one for each day of National Punctuation Week and one for the following Monday with the final answer. Each day people will e-mail their answers to the day’s question to us. From the correct entries we’ll draw three names, and those people will be awarded a prize of Bank of America merchandise. To honor the day, we will wear your T-shirts and enjoy a fun week celebrating and learning good punctuation! Marie Gayed Thank you for providing us a light-hearted opportunity to teach punctuation! Happy National Punctuation Day! Karen Nelson and Marie Gayed Tampa (Florida) Legal Bank of America Karen Nelson 2006 contest Question for Monday, September 25 How many true punctuation marks are on the standard keyboard? (a) Fewer than 12 (b) 15 to 22 (c) 25 to 32 Question for Tuesday, September 26 What was the first widely used Roman punctuation mark? (a) Period (b) Interrobang (c) Interpunct Question for Wednesday, September 27 Who was known as the Father of Italic Type and was also the first printer to use the semicolon? He was the first to print pocket-sized books so that the classics would be available to the masses. Question for Thursday, September 28 Which of the following punctuation marks have no equivalent in speech? (a) comma and period (b) colon and semicolon (c) question mark and exclamation mark Question for Friday, September 29 What is the name of this symbol: "¶"? ANSWERS Monday, September 25: (b). -

Via Egnatia: the Dyrrachion- Philippoi Itinerary

VIA EGNATIA: THE DYRRACHION- PHILIPPOI ITINERARY. (START TO XI CENTURY) *** Afrim HOTI- Damianos KOMATAS *** After the creation of the roman province of Macedonia a new street infra- structure development strategy emerged. Cicero (106-43 BC) described this new strategy with the well-known expression “nostra militare”1. Several dis- tinct archeological objects (relieves, milestones and especially carved inscrip- tions) as well as written documents, specifically talk about the characteristics of this street. More specifically these evidences show that this road has been used as a military road (Fig. 1), as well as a principal artery of interregional commerce2. Egnatia got its final shape after many construction and reconstruction phases. Based on data given by Polybius (200-120 BC), the road, built by the Macedonian consul Gnaeus Egnatius between years 146-143 BC, connected Apolonia of Illiry with Thessaloniki, spawning a distance of 267 miles (395 km)3. As time passed by, the colony of Dyrrachium (Fig. 2) became the starting point of Egnatia, with the length increasing to 553 miles (830 km) as this street reached Byzant. Many existing road infrastructures were used in several segments of this road. According to Strabon’ s (63 BC- 24 AD) Geographica the stone road found on the side of Shkumbini’s valley followed the previous street line of the Illyrian street “Candavia” 4. 1 F. Walbank, "Via illa nostra militaris: Some Thoughts on the Via Egnatia," Althistorische Stu- dien: Hermann Bengtson zum 70. Geburtstag dargebracht (Wiesbaden 1983) 131-147. 2V. Shtylla, Rrugët dhe urat e vjetra në Shqipëri, Tiranë , 1998, 37 ; N. Ceka, Iliret, 2001, 178-179; A.