1 Researching State Rescaling in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wt/Tpr/G/375

RESTRICTED WT/TPR/G/375 6 June 2018 (18-3454) Page: 1/23 Trade Policy Review Body Original: English TRADE POLICY REVIEW REPORT BY CHINA Pursuant to the Agreement Establishing the Trade Policy Review Mechanism (Annex 3 of the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization), the policy statement by China is attached. Note: This report is subject to restricted circulation and press embargo until the end of the first session of the meeting of the Trade Policy Review Body on China. WT/TPR/G/375 • China - 2 - Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 3 2 NEW ERA, NEW THOUGHT AND NEW VISION ............................................................... 3 3 APPLYING A NEW DEVELOPMENT VISION AND ESTABLISHING NEW INSTITUTIONS OF AN OPEN ECONOMY ............................................................................ 4 3.1 Setting new mechanisms for sustainable trade development .............................................. 4 3.2 Creating more attractive investment environment ............................................................ 5 3.3 Supporting outbound direct investment cooperation for mutual benefits and win-win with host countries and regions ............................................................................................ 8 3.4 Strengthening the protection of intellectual property rights ................................................ 8 3.5 Building pilot free trade zones according to high standard ................................................ -

I. Guides to the State of the Field Song Research Tools

I. Guides to the State of the Field Page 1 of 125 Song Research Tools home | about | faq I. Guides to the State of the Field The late Etienne Balazs began formulating plans for an international, collaborative study of the Sung period as early as 1949 and formally initiated the "Sung Project" in 1954. The Project was responsible for some of the most valuable reference tools in this guide. Its history is related in: Ref (W) DS751.S86 1978x Yves Hervouet, "Introduction," (W) DS751.S86 1978x A Sung Bibliography Loc: Z3102 .S77 Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 1978, pp. vii-xiv. I.A. SOCIETIES, NEWSLETTERS, AND JOURNALS Societies Japan: Sōdaishi kenkyūkai 宋代史研究会 (Society for Song Studies): http://home.hiroshima-u.ac.jp/songdai/songdaishi-yanjiuhui.htm This site contains announcements for and reports on the annual meetings of the society, links to related sites, a bibliography of Japanese scholarship on Song studies (1982-2002) and a directory of Japanese scholars working in the field. Sōdaishi danwakai 宋代史談話會 (Society for the Study of Song History in Japan) http://www2u.biglobe.ne.jp/~songsong/songdai/danwakai.html Established in 1997 as a forum and reading group for young scholars of Song history active in Kyoto-Osaka-Kobe region. Includes meeting information, list of readings, and an announcement board. Sōdai shibun kenkyūkai 宋代詩文研究會 (Society for the Study of Song Literature) http://www9.big.or.jp/~co-ume/song/ http://www9.big.or.jp/~co-ume/song/danwakai.htm Includes announcements and a mailing list. Registration is required to get access to the full site. -

English/ and New York City—8.538 Million in 2016; 789 Km

OVERVIEW Public Disclosure Authorized CHONGQING Public Disclosure Authorized 2 35 Public Disclosure Authorized SPATIAL AND ECONOMIC TRANSFORMATION FOR A GLOBAL CITY Public Disclosure Authorized Photo: onlyyouqj. Photo: © 2019 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, inter- pretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judg- ment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to World Bank Publications, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522-2625; e-mail: [email protected]. Citation Please cite the report as follows: World Bank. 2019. Chongqing 2035: Spatial and Economic Transfor- mation for a Global City. Overview. Washington, DC: World Bank. -

Invest in Chongqing Liangjiang New Area by China Italy Chamber of Commerce Chongqing Office 2020 CONTENT

Invest in Chongqing Liangjiang New Area By China Italy Chamber of Commerce Chongqing Office 2020 CONTENT 01 02 03 04 Liangjiang New Area – National Strategy The first national open area in inland China Established on June 18th, 2010, Liangjiang New Area is the third national open area directly approved by the State Council, ranking after Putong New Area in Shanghai, Binhai New Area in Tianjin. Liangjiang New Area covers 40% of the area of Chongqing city and has a population of about 2.35 million inhabitants. It is expected that by 2025, the population of the area may reach 5 million. Unit Price(RMB/KWh) Catalogue 1-10 35-110 110 >220KV KV KV KV Large Industrial 0.6057 0.5807 0.5657 0.5557 Electricity Supply Drainage Catalogue 3 3 Total Payable Unit Price (RMB/M ) (RMB/M ) Catalogue 3 (Yuan/M3) (RMB/M ) Industrial 3.25 1.3 4.55 Industrial 2.32 Policy Preferences The corporate income tax shall be imposed at a reduced rate of VAT TAX 15% High Talent Rewarding 100% of the contribution to the local economic Reward development of Liangjiang according to the salary income One Company One Policy” ( 一企一策 ) National key laboratory --- 500 MRMB R&D National Engineering Technology Research Center --- 400MRMB Innovation National level international science and technology cooperation base --- Reward 150MRMB Other Accroding to the sectors of the inductry, the total investment value and Incentives Annual value of production, Liangjiang will provide 100MRMB-500MRMB incentives to the company 1. The average price of land lease: 1st floor RMB 30 – 80 / SQM / Month; 2nd floor RMB 25 – 50 / SQM /Month; 3rd floor RMB 15 – 30 / SQM /Month; 2. -

2020 NN Development Zone Directory4

Development Zone Directory Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang 2020 Contents Introduction 4 Shanghai 6 Jiangsu 11 Zhejiang 22 Others 32 Imprint Address Publisher: SwissCham China SwissCham Shanghai Administrator: SwissCham Shanghai Carlton Building, 11th Floor, Room1138, 21 Project execution, editorial and Huanghe Road, Shanghai, 200003. P. R. translations: Nini Qi (lead), China Eric Ma 中国上海市黄河路21号鸿祥大厦1138室 邮编 Project direction: Peter Bachmann :200003 Tel: 021 5368 1248 Copyright 2020 SwissCham China Web: https://www.swisscham.org/shanghai/ 2 Development Zone Directory 2020 Dear Readers, A lot has changed since we published our first edition of the Development Zone Directory back in 2017. But China remains one of the top investment hotspots in the world, despite ongoing trade and other disputes the country faces. While it is true that companies and countries are relocating or building up additional supply chains to lessen their dependence on China, it is also a fact that no other country has the industrial capacity, growing middle class and growth potential. The Chinese market attracts the most foreign direct investment and it well may do so for many years to come, given the large untapped markets in the central and western part of the country. Earlier this year, Premier Li Keqiang mentioned that there are 600 million Chinese citizens living with RMB 1,000 of monthly disposable income. While this may sounds surprising, it also shows the potential that Chinese inner regions have for the future. Investing in China and selling to the Chinese consumers is something that makes sense for companies from around the world. The development zones listed in this directory are here to support and help foreign investors to deal with the unique challenges in the Chinese market. -

P020200328433470342932.Pdf

In accordance with the relevant provisions of the CONTENTS Environment Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China, the Chongqing Ecology and Environment Statement 2018 Overview …………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 is hereby released. Water Environment ………………………………………………………………………………… 3 Atmospheric Environment ………………………………………………………………………… 5 Acoustic Environment ……………………………………………………………………………… 8 Solid and Hazardous Wastes ………………………………………………………………………… 9 Director General of Chongqing Ecology Radiation Environment …………………………………………………………………………… 11 and Environment Bureau Landscape Greening ………………………………………………………………………………… 12 May 28, 2019 Forests and Grasslands ……………………………………………………………………………… 12 Cultivated Land and Agricultural Ecology ………………………………………………………… 13 Nature Reserve and Biological Diversity …………………………………………………………… 15 Climate and Natural Disaster ……………………………………………………………………… 16 Eco-Priority & Green Development ………………………………………………………………… 18 Tough Fight for Pollution Prevention and Control ………………………………………………… 18 Ecological environmental protection supervision …………………………………………………… 19 Ecological Environmental Legal Construction ……………………………………………………… 20 Institutional Capacity Building of Ecological Environmental Protection …………………………… 20 Reform of Investment and Financing in Ecological Environmental Protection ……………………… 21 Ecological Environmental Protection Investment …………………………………………………… 21 Technology and Standards of Ecological Environmental Protection ………………………………… 22 Heavy Metal Pollution Control ……………………………………………………………………… 22 Environmental -

2020 Annual Report 2020 Contents

CHONGQING MACHINERY & ELECTRIC CO., LTD. CHONGQING MACHINERY (a joint stock limited company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) Stock Code: 02722 ANNUAL REPORT 2020 ANNUAL REPORT 2020 ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS Corporate Information 2 Financial Highlights 4 Group Structure 5 Results Highlights 6 Chairman’s Statement 7 Management’s Discussion and Analysis 24 Directors, Supervisors and Senior Management 45 Report of the Board of Directors 63 Report of the Supervisory Committee 90 Corporate Governance Report 93 Risk and Internal Control and Governance Report 112 Environmental, Social and Governance Report 120 Independent Auditor’s Report 150 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 160 Statement of Financial Position of the Company 164 Consolidated Income Statement 167 Income Statement of the Company 170 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 172 Cash Flows Statement of the Company 175 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 177 Statement of Changes in Equity of the Company 181 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 185 Supplementary Information to Consolidated Financial Statements 471 Corporate Information DIRECTORS COMMITTEES UNDER BOARD OF DIRECTORS Executive Directors Members of the Audit and Risk Management Mr. Zhang Fulun (Chairman) Committee Ms. Chen Ping Mr. Yang Quan Mr. Lo Wah Wai (Chairman) Mr. Jin Jingyu Non-executive Directors Mr. Liu Wei Mr. Dou Bo Mr. Huang Yong Mr. Zhang Yongchao Members of the Remuneration Committee Mr. Dou Bo Mr. Wang Pengcheng Mr. Ren Xiaochang (Chairman) Mr. Lo Wah Wai Independent Non-executive Directors Mr. Jin Jingyu Mr. Huang Yong Mr. Lo Wah Wai Mr. Ren Xiaochang Members of the Nomination Committee Mr. Jin Jingyu Mr. -

Legal Updates

8th Edition of 2014 Legal Updates 1. SAFE Circular 36 Changes Policy for the Settlement of Foreign Exchange Capital, Benefitting Foreign-invested PE Funds and Ordinary Foreign-invested Enterprises 2. CBRC Issues Interim Provisions on the Administration of Specialized Subsidiaries of Financial Leasing Companies Legal Updates 1. SAFE Circular 36 Changes Policy for the Settlement of Foreign Exchange Capital, Benefitting Foreign-invested PE Funds and Ordinary Foreign-invested Enterprises (Authors: Yong WANG, Qian LI) On July 15, 2014, China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange (“SAFE”) issued the Circular of the State Administration of Foreign Exchange on Issues Concerning the Pilot Reform of the Administrative Approach to the Settlement of Foreign Exchange Capital of Foreign-invested Enterprises in Certain Areas (Hui Fa [2014] No. 36) (“Circular 36”).Circular 36 promotes discretionary settlement of foreign exchange capital in 16 pilot areas. They areTianjin Binhai New Area, Economy Group of Shenyang, Suzhou Industrial Park, Donghu National Independent Innovation Demonstration Zone, Guangzhou Nansha New Area, Hengqin New Area, Chengdu High-tech Industrial Development Zone, Zhongguancun Science Park [in Beijing], Chongqing Liangjiang New Area, the border development and opened regions in Heilongjiang Province where pilot foreign exchange administrative reform is implemented, Wenzhou Comprehensive Financial Reform Pilot Area, Pingtan Comprehensive Experimental Area, China-Malaysia Qinzhou Industrial Park, Guiyang Comprehensive Bonded Zone, Qianhai Shenzhen-Hong Kong Modern Service Industry Cooperation Zone and Qingdao Comprehensive Wealth Management and Financial Reform Pilot Area.1 Circular 36 became effective on August 4, 2014 and supersede prior provisions in the event there is a conflict between Circular 36 and those provisions. -

China's Fintech

China’s FinTech: the End of the Wild West POLICY PAPER APRIL 2021 Institut Montaigne is a nonprofit, independent think tank based in Paris, France. Our mission is to craft public policy proposals aimed at shaping political debates and decision making in France and Europe. We bring together leaders from a diverse range of backgrounds – government, civil society, corporations and academia – to produce balanced analyses, international benchmarking and evidence-based research. We promote a balanced vision of society, in which open and competitive markets go hand in hand with equality of opportunity and social cohesion. Our strong commitment to representative democracy and citizen participation, on the one hand, and European sovereignty and integration, China’s FinTech: on the other, form the intellectual basis for our work. Institut Montaigne is funded by corporations and individuals, none of whom contribute to more than 3% of its annual budget. the End of the Wild West POLICY PAPER – APRIL 2021 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Viviana Zhu is the Policy Officer for Institut Montaigne’s Asia Program. She became the editor of the Institute’s quarterly publication, China Trends, in March 2020. Before joining Institut Montaigne in January 2019, Viviana worked as Coordinator of the Asia Program of the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR). She was responsible for event coordination, reporting, and research support. She holds a Master’s degree in International Politics and a Bachelor’s degree in Politics and Economics from the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, where her primary focus was China and international politics. In May 2020, she has co-authored an Institut Montaigne policy paper, “Fighting COVID-19: East Asian Responses to the Pandemic” (with Mathieu Duchâtel and François Godement). -

Landmark Food and the Construction of Food Tourism City of Chongqing Ma Jianlin Chongqing Business Vocational College, Chongqing 4001331

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 220 3rd International Conference on Education, E-learning and Management Technology (EEMT 2018) Landmark Food and the Construction of Food Tourism City of Chongqing Ma Jianlin Chongqing Business Vocational College, Chongqing 4001331 Keywords: Landmark food; food Tourism; city construction Abstract. The concept and formation of landmark food has been recognized by most people. Among the six elements of tourism, food is indispensable for people’s life, and is also dominated in tourism income. Combining the development of landmark food and local tourism in Chongqing, this paper put forward the importance of developing food Tourism in Chongqing, and proposed to develop food tourism according to the regional differentiation, create landmark food stores and special food street to build a city for food Tourism and enhances the image of city tourism. 1. Introduction Tourism has become an indispensable part of people’s life. It the era of mass tourism, people travel frequently and have accumulated a wealth of experience. Meanwhile, the demand for tourism has gradually become personalized and diverse. How people interpret tourism changes greatly. Travelers are no longer satisfied with the traditional way of tourism, that is, get a hurried and cursory glance at the scenery, but prefer to obtain spiritual and cultural satisfaction through tourism. Tourism motives are gradually diversified. And food Tourism which aims at enjoyment and experience has gradually become the mainstream of tourism. In 2017, according to the sample survey statistics, the average overnight spending of domestic tourists reached 1369.84 Yuan per capita. In terms of cost allocation, food and beverage accounted for 17.82%, accommodation accounted for 24.30%, shopping accounted for 14.43%, and transportation accounted for 14.00% 1. -

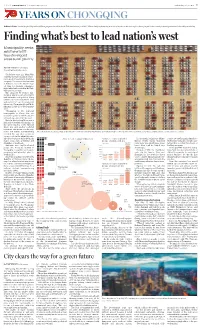

Finding What's Best to Lead Nation's West

CHINA DAILY | HONG KONG EDITION Wednesday, July 31, 2019 | 7 years onYEARS ON CHONGQING Editor's Note: As the People’s Republic of China prepares to celebrate its 70th anniversary on Oct 1, China Daily is featuring a series of stories on the role regions have played in the country’s development and where they are today. Finding what’s best to lead nation’s west Municipality seeks solutions to lift lessdeveloped areas out of poverty By TAN YINGZI in Chongqing [email protected] Until three years ago, Meng Min could barely have imagined return ing home to Chongqing to start up a company. The former chief scientist at Covance, one of the world’s larg est drug development companies, had studied and worked in the Unit ed States for 24 years. But attracted by China’s fast growing pharmaceutical industry and favorable local policies, Meng returned to her hometown in 2016 and started her own bioanalytical laboratory, Chongqing Denali Med pharma, in the city’s development zone. “Chongqing is the youngest municipality in China. You can reach your goals here if you have sol id knowledge and skills,” she said. Back in 1980s when Meng was a high school student, Chongqing, on the upper reaches of the Yangtze River, was just another polluted industrial city known for its large motor and vehicle manufacturing An aerial view of cars parked at Guoyuan Port in Chongqing, waiting to be transported to other parts of the country along the Yangtze River. WANG QUANCHAO / XINHUA industry. She and other ambitious young people in the inland city usu ally chose to pursue their dreams in Area: 82,402 square kilometers Annual per capita disposable In the north, it links the China yuan to set up Chongqing OneSpace major cities, such as Beijing and income of urban residents Europe freight trains, launched Technology Company, enough capi Shanghai, or go abroad. -

Chongqing Service Guide on 72-Hour Visa-Free Transit Tourists

CHONGQING SERVICE GUIDE ON 72-HOUR VISA-FREE TRANSIT TOURISTS 24-hour Consulting Hotline of Chongqing Tourism Administration: 023-12301 Website of China Chongqing Tourism Government Administration: http://www.cqta.gov.cn:8080 Chongqing Tourism Administration CHONGQING SERVICE GUIDE ON 72-HOUR VISA-FREE TRANSIT TOURISTS CONTENTS Welcome to Chongqing 01 Basic Information about Chongqing Airport 02 Recommended Routes for Tourists from 51 COUNtRIEs 02 Sister Cities 03 Consulates in Chongqing 03 Financial Services for Tourists from 51 COUNtRIEs by BaNkChina Of 05 List of Most Popular Five-star Hotels in Chongqing among Foreign Tourists 10 List of Inbound Travel Agencies 14 Most Popular Traveling Routes among Foreign Tourists 16 Distinctive Trips 18 CHONGQING SERVICE GUIDE ON 72-HOUR VISA-FREE TRANSIT TOURISTS CONTENTS Welcome to Chongqing 01 Basic Information about Chongqing Airport 02 Recommended Routes for Tourists from 51 COUNtRIEs 02 Sister Cities 03 Consulates in Chongqing 03 Financial Services for Tourists from 51 COUNtRIEs by BaNkChina Of 05 List of Most Popular Five-star Hotels in Chongqing among Foreign Tourists 10 List of Inbound Travel Agencies 14 Most Popular Traveling Routes among Foreign Tourists 16 Distinctive Trips 18 Welcome to Chongqing A city of water and mountains, the fashion city Chongqing is the only municipality directly under the Central Government in the central and western areas of China. Numerous mountains and the surging Yangtze River passing through make the beautiful city of Chongqing in the upper reaches of the Yangtze River. With 3,000 years of history, Chongqing, whose civilization is prosperous and unique, is a renowned city of history and culture in China.