Action on Bullying

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Print Finishers

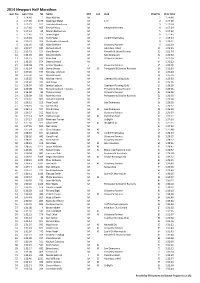

2014 Newport Half Marathon Gun Pos Gun Time No Name M/F Cat Club Chip Pos Chip Time 1 1:14:46 1 Ryan McFlyn M 1 1:14:46 2 1:17:09 1175 Matthew Welsh M 1 Tri 2 1:17:08 3 1:17:15 910 Leighton Rawlinson M 3 1:17:14 4 1:17:30 865 Emrys Penny M Newport Harriers 4 1:17:29 5 1:17:43 68 Maciej Bialogonski M 5 1:17:42 6 1:17:46 316 James Elgar M 6 1:17:45 7 1:19:35 372 Tom Foster M Cardiff Triathletes 7 1:19:34 8 1:20:33 926 Christopher Rennick M 8 1:20:31 9 1:21:10 425 Mike Griffiths M Lliswerry Runners 9 1:21:09 10 1:21:27 680 Richard Lloyd M Aberdare VAAC 10 1:21:25 11 1:21:52 117 Gary Brown M Penarth & Dinas Runners 11 1:21:50 12 1:22:03 801 Doug Nicholls M San Domenico 12 1:22:02 13 1:22:21 625 Alun King M Lliswerry Runners 13 1:22:18 14 1:22:25 574 Dean Johnson M 14 1:22:22 15 1:22:38 772 Emma Wookey F Lliswerry Runners 15 1:22:36 16 1:22:54 256 Steve Davies M 50 Pontypool & District Runners 16 1:22:52 17 1:25:26 575 Nicholas Johnson M 17 1:25:24 18 1:25:50 597 Richard Jones M 18 1:25:39 19 1:25:55 458 Michael Harris M Caerleon Running Club 19 1:25:53 20 1:26:02 163 Jack Casey M 20 1:25:56 21 1:26:07 162 James Casburn M Caerleon Running Club 22 1:26:05 22 1:26:08 541 Richard Jackson-Hookins M Penarth & Dinas Runners 23 1:26:06 23 1:26:09 82 Thomas Bland M Lliswerry Runners 24 1:26:06 24 1:26:09 531 Mark Hurford M Pontypool & District Runners 21 1:26:03 25 1:26:10 803 Daniel Oakenfull M 25 1:26:08 26 1:26:12 215 Pete Croall M San Domenico 26 1:26:10 27 1:26:15 57 Jon Belcher M 27 1:26:12 28 1:26:43 107 Phil Bristow M 50 San Domenico 28 1:26:40 -

Coridor-Yr-M4-O-Amgylch-Casnewydd

PROSIECT CORIDOR YR M4 O AMGYLCH CASNEWYDD THE M4 CORRIDOR AROUND NEWPORT PROJECT Malpas Llandifog/ Twneli Caerllion/ Caerleon Llandevaud B Brynglas/ 4 A 2 3 NCN 4 4 Newidiadau Arfaethedig i 6 9 6 Brynglas 44 7 Drefniant Mynediad/ A N tunnels C Proposed Access Changes 48 N Pontymister A 4 (! M4 C25/ J25 6 0m M4 C24/ J24 M4 C26/ J26 2 p h 4 h (! (! p 0 Llanfarthin/ Sir Fynwy/ / 0m 4 u A th 6 70 M4 Llanmartin Monmouthshire ar m Pr sb d ph Ex ese Gorsaf y Ty-Du/ do ifie isti nn ild ss h ng ol i Rogerstone A la p M4 'w A i'w ec 0m to ild Station ol R 7 Sain Silian/ be do nn be Re sba Saint-y-brid/ e to St. Julians cla rth res 4 ss u/ St Brides P M 6 Underwood ifi 9 ed 4 ng 5 Ardal Gadwraeth B M ti 4 Netherwent 4 is 5 x B Llanfihangel Rogiet/ 9 E 7 Tanbont 1 23 Llanfihangel Rogiet B4 'St Brides Road' Tanbont Conservation Area t/ Underbridge en Gwasanaethau 'Rockfield Lane' w ow Gorsaf Casnewydd/ Trosbont -G st Underbridge as p Traffordd/ I G he Newport Station C 4 'Knollbury Lane' o N Motorway T Overbridge N C nol/ C N Services M4 C23/ sen N Cyngor Dinas Casnewydd M48 Pre 4 Llanwern J23/ M48 48 Wilcrick sting M 45 Exi B42 Newport City Council Darperir troedffordd/llwybr beiciau ar hyd Newport Road/ M4 C27/ J27 M4 C23A/ J23A Llanfihangel Casnewydd/ Footpath/ Cycleway Provided Along Newport Road (! Gorsaf Pheilffordd Cyffordd Twnnel Hafren/ A (! 468 Ty-Du/ Parcio a Theithio Arfaethedig Trosbont Rogiet/ Severn Tunnel Junction Railway Station Newport B4245 Grorsaf Llanwern/ Trefesgob/ 'Newport Road' Rogiet Rogerstone 4 Proposed Llanwern Overbridge -

Great Western Signal Box Diagrams 22/06/2020 Page 1 of 40

Great Western Signal Box Diagrams Signal Box Diagrams Signal Box Diagram Numbers Section A: London Division Section B: Bristol Division Section E: Exeter Division Section F: Plymouth Division Section G: Gloucester Division Section H: South Wales Main Line Section J: Newport Area Section K: Taff Vale Railway Section L: Llynvi & Ogmore Section Section M: Swansea District Section N: Vale of Neath Section P: Constituent Companies Section Q: Port Talbot & RSB Railways Section R: Birmingham Division Section S: Worcester Division Section T: North & West Line Section U: Cambrian Railways Section W: Shrewsbury Division Section X: Joint Lines Diagrams should be ordered from the Drawing Sales Officer: Ray Caston 22, Pentrepoeth Road, Bassaleg, NEWPORT, Gwent, NP10 8LL. Latest prices and lists are shown on the SRS web site http://www.s-r-s.org.uk This 'pdf' version of the list may be downloaded from the SRS web site. This list was updated on: 10th April 2017 - shown thus 29th November 2017 - shown thus 23rd October 2018 - shown thus 1st October 2019 - shown thus 20th June 2020 (most recent) - shown thus Drawing numbers shown with an asterisk are not yet available. Note: where the same drawing number appears against more than one signal box, it indcates that the diagrams both appear on the same sheet and it is not necessary to order the same sheet twice. Page 1 of 40 22/06/2020 Great Western Signal Box Diagrams Section A: London Division Section A: London Division A1: Main Line Paddington Arrival to Milton (cont'd) Drawing no. Signal box A1: Main Line Paddington Arrival to Milton Burnham Beeches P177 Drawing no. -

Governors' Annual Report to Parents

Governors’ Annual Report to Parents December 2019 Welsh language version available on request Governors’ Annual Report to Parents - 2019 On behalf of the Governing Body and Acting Headteacher, we would like to take this opportunity to thank you as parents, and the whole community for your support of St Julian’s School. Over this past academic year, the staff and governors have continued to work hard to develop the quality and provision of the education provided to all learners. The Governing Body has played a fundamental role in both supporting and challenging the school to ensure progress continues at St Julian’s at the appropriate pace. We hope that you have already had the opportunity to visit our evolving website and I would ask you to pay particular attention to the Governing Body web pages which can be found in ‘About Us.’ We continue to use these to ensure that the school community can access the work of the Governing Body, and the different roles we hold. We also ensure that we have parent governors available at all parents evenings so that parents can get in touch with their representatives more easily. As the report outlines we have paused to celebrate our success but also re-focused on the ongoing challenges ahead. Your role as parents / carers continues to be vital in not only supporting your children but communicating with us and providing helpful self-evaluation information on our work. The Governors, Acting Headteacher and staff are determined to ensure that the school continues to work tirelessly to develop our provision over the coming years and provide the quality of education that all our students deserve in meeting the national aspirations of becoming ambitious capable learners who are confident and able to make a successful contribution to society in Wales. -

Planning Application Schedule PDF 2 MB

Report Planning Committee Part 1 Date: 6 July 2016 Item No: 5 Subject Planning Application Schedule Purpose To take decisions on items presented on the attached schedule Author Head of Regeneration, Investment and Housing Ward As indicated on the schedule Summary The Planning Committee has delegated powers to take decisions in relation to planning applications. The reports contained in this schedule assess the proposed development against relevant planning policy and other material planning considerations, and take into consideration all consultation responses received. Each report concludes with an Officer recommendation to the Planning Committee on whether or not Officers consider planning permission should be granted (with suggested planning conditions where applicable), or refused (with suggested reasons for refusal). The purpose of the attached reports and associated Officer presentation to the Committee is to allow the Planning Committee to make a decision on each application in the attached schedule having weighed up the various material planning considerations. The decisions made are expected to benefit the City and its communities by allowing good quality development in the right locations and resisting inappropriate or poor quality development in the wrong locations. Proposal 1. To resolve decisions as shown on the attached schedule. 2. To authorise the Head of Regeneration, Investment and Housing to draft any amendments to, additional conditions or reasons for refusal in respect of the Planning Applications Schedule attached Action by Planning Committee Timetable Immediate This report was prepared after consultation with: . Local Residents . Members . Statutory Consultees The Officer recommendations detailed in this report are made following consultation as set out in the Council’s approved policy on planning consultation and in accordance with legal requirements. -

DIOCESAN PRAYER CYCLE – September 2020

DIOCESAN PRAYER CYCLE – September 2020 The Bishop’s Office Diocesan Chancellor – Bishop Bishop Cherry Mark Powell 01 Bishop’s P.A. Vicki Stevens Diocesan Registrar – Tim Russen Cathedral Chapter 02 Newport Cathedral Canons and Honorary Jonathan Williams Canons The Archdeaconry of Archdeacons - Area Deans – Monmouth Ambrose Mason Jeremy Harris, Kevin Hasler, Julian Gray 03 The Archdeaconry of Newport Jonathan Williams John Connell, Justin Groves The Archdeaconry of the Gwent Sue Pinnington Mark Owen Valleys Abergavenny Ministry Area Abergavenny, Llanwenarth Citra, Julian Gray, Gaynor Burrett, Llantilio Pertholey with Bettws, Heidi Prince, John Llanddewi Skirrid, Govilon, Humphries, Jeff Pearse, John Llanfoist, Llanelen Hughes, Derek Young, Llantilio Pertholey CiW Llanfihangel Crucorney, Michael Smith, Peter Cobb, Primary School 04 Cwmyoy, Llanthony, Llantilio Lorraine Cavanagh, Andrew Crossenny, Penrhos, Dawson, Jean Prosser, Llanvetherine, Llanvapley, Andrew Harter Director of Ministry – Llandewi Rhydderch, Ambrose Mason Llangattock-juxta-Usk, LLMs: Gaynor Parfitt, Gillian Llansantffraed, Grosmont, Wright, Clifford Jayne, Sandy Skenfrith, Llanfair, Llangattock Ireson, William Brimecombe Lingoed Bassaleg Ministry Area Christopher Stone 05 Director of Mission – Anne Golledge Bassaleg, Rogerstone, High Cross Sue Pinnington Bedwas with Machen Ministry Dean Aaron Roberts, Richard Area Mulcahy, Arthur Parkes 06 Diocesan Secretary – Bedwas, Machen, Rudry, Isabel Thompson LLM: Gay Hollywell Michaelston-y- Fedw Blaenavon Ministry Area Blaenavon -

Christmas 2018

The LINK Community Magazine Christmas 2018 Produced and distributed by the members and friends of St Julian’s Baptist Church 35 Beaufort Road, Newport, NP19 7PZ Tel: 01633 661952 www.sjbaptist.co.uk Registered charity 1148152 Newport Night Shelter 2018—2019 During the coldest winter months, a group of Newport churches open their doors and hearts to welcome in the city’s homeless Christmas lunch from the streets. We provide a hot supper and drinks, a warm, If you will be alone this Christmas and would like some company, safe bed for the night, toiletries, breakfast in the morning, we would be delighted to have you at our Christmas Lunch. and genuine friendship. Night shelter 2018-19 is up and running. Please contact Jan on 01633 678789 for further details. We are excited once again to be able to provide emergency accommodation to homeless people this winter in partnership with Newport churches. ZOOPERS The first night (26 Nov) got off to an excellent start, with everything going smoothly. We had a total of 14 referrals Breakfast and After School Club asking for emergency assistance, with 9 people accessing the shelter. at St Julian’s Baptist Church Hall Work now starts to find homes for those who we are supporting. Beaufort Rd, Newport, NP19 7PZ St Julian’s Baptist Church are accommodating the homeless on Saturday nights through till the end of January 2019. Fun, stimulating and safe Childcare. Pick up and drop off to St. Julian’s Primary School. Children from other schools accepted Many thanks indeed to all the volunteers, without whom although own transport must be provided. -

February 2021 Prayer Cycle

DIOCESAN PRAYER CYCLE – February 2021 The Bishop’s Office Diocesan Chancellor – Bishop Bishop Cherry Mark Powell 01 Bishop’s Chaplain Jonathan Williams Bishop’s P.A. Vicki Stevens Diocesan Registrar – Tim Russen Newport Cathedral Dean (designate) Ian Black 02 College of Canons Precentor Jonathan Williams Associate Priest David Neale The Archdeaconry of Archdeacons - Area Deans – Monmouth Jeremy Harris, Kevin Hasler, Julian Gray 03 The Archdeaconry of Newport Jonathan Williams John Connell, Justin Groves The Archdeaconry of the Gwent Sue Pinnington Mark Owen Valleys Abergavenny Ministry Area Julian Gray, Gaynor Burrett, Heidi Prince, John Abergavenny, Llanwenarth Citra, Humphries, Llantilio Pertholey with Bettws, Jeff Pearse, John Hughes, Llanddewi Skirrid, Govilon, Derek Young, Michael Smith, Llanfoist, Llanelen Peter Cobb, Lorraine Llantilio Pertholey CiW Llanfihangel Crucorney, Cavanagh, Andrew Dawson, Primary School 04 Cwmyoy, Llanthony, Llantilio Jean Prosser, Andrew Harter, Crossenny, Penrhos, Michael Marsden, Ian Llanvetherine, Llanvapley, Aveson, Mary Moore, Director of Mission – Llandewi Rhydderch, Andrew Willie, Francis Sue Pinnington Llangattock-juxta-Usk, Buxton, Marc Winchester Llansantffraed, Grosmont, Skenfrith, Llanfair, Llangattock LLMs: Gaynor Parfitt, Gillian Lingoed Wright, Clifford Jayne, Sandy Ireson, William Brimecombe Bassaleg Ministry Area Christopher Stone Diocesan Secretary – 05 Anne Golledge Isabel Thompson Bassaleg, Rogerstone, High Cross Diocesan Director of Education – Andrew Bedwas with Machen Ministry Dean -

Lliswerry Runners Juniors

CLUB CHAMPIONSHIP 2021 ⇒ OVERVIEW EXPLANATION & ETHOS ⇒ The Club Championship consists of 14 events, with varying distances and terrain, spread throughout the year. Individuals do not need to complete all races, as individuals’ final positions will be based on their 6 best events. ⇒ When selecting events, a number of considerations were made, including: • Having a range of different types of events, i.e. Distance, terrain etc. • Event capacity and thus capability for individuals to have a fair opportunity to obtain an entry • Event costs have also been considered, with the majority of events not being prohibitively expensive • Having a range of local events • Having a range of week days on which events take place ⇒ The Club Championship is inclusive and encourages friendly rivalry within individuals’ training groups and across the club as whole. It also encourages individuals to try different types of events, that they may not otherwise have considered. ⇒ Each event will be ranked by one of the following methods: • Finishing Position / Time • Age-Grade • Participation Points - 75 points are awarded to each individual that takes part ⇒ Each event will then be scored in accordance with the rankings (i.e. Points are allocated from 150 for first place, down to 1 for 150th place [Men / Ladies are scored separately] - If there are more than 150 participants, each of the individuals ranked below 150 will score 1 point each). ⇒ For the Points League, individuals will be split by the following age categories (They remain in the age category in -

Ward Overview 2014

Ward Overview 2014 City of Newport V1.2 October 2014 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Section 1: Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 2 Context ................................................................................................................................................ 2 Positive News for Newport ................................................................................................................. 5 Issues of Concern for Newport ............................................................................................................ 7 Overview of Newport ........................................................................................................................ 10 Section 2: Census of Population and Households .............................................................................. 14 Section 3: Newport and the Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation (WIMD) ....................................... 35 Income and Employment .................................................................................................................. 40 Health ................................................................................................................................................ 42 Education .......................................................................................................................................... -

Liswerry Notice of Poll

CYNGOR DINAS CASNEWYDD NEWPORT CITY COUNCIL RHYBUDD PLEIDLEISIO NOTICE OF POLL ETHOL CYNGHORYDD DINESIG ELECTION OF CITY COUNCILLORS RHANBARTH ETHOLIADOL LLISWERRY ELECTORAL DIVISION OF LISWERRY RHYBUDDIR TRWY HYN: NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN THAT: Y bydd pleidleisio 4 Cynghorwyr Dinas dros y Rhanbarth Etholidial a enwyd uchod or Ddydd Iau, 04 Mai 2017, A Poll for the Election of 4 City Councillors for the above named Electoral Division, will be held on 04/05/17 rhwng 7 o'r gloch y bore a 10 o'r gloch yr hwyr. between 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. Y mae enwau, cyfeiriad y cartref, a disgrifiad (os oes un) o'r Ymgeisydd a erys ar dir cyfreithlon i'w hethol, ac The full names, home address and description (if any) of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for enwau'r personau a lofnododd Bapur Enwebu pob Ymgeisydd fel a ganlyn:- election and the names of the persons who signed the Nomination Paper for each Candidate are as follows:- Enwau'r Ymgeisydd Cyfeiriad Y Cartref Disgrifiad (Cyfenw yn gyntaf) (Yn Llawn) (Os oes un) Enwau'r Holl Bersonau Yn Llofnodi Papur Enwebu Ymgeisydd Name of Candidates Home Address Description Names of all the Persons Signing the Candidate's Nomination Paper (Surname first) (In Full) (If any) CLARK 3 Oaks Close, Newport, NP20 3GD Welsh Conservative Party Ramsey Colin(+) Nevison Marian R(++) Nicholas Ryan Candidate Wood Robert Morgan Terence L Powell Sarah J Yarham Brian D Cooper Jennifer A Mochizuki-Ward Kayleigh Kemp Susan M Wright Victoria COX 14 Preston Avenue, Newport, NP20 4JE Welsh Conservative Party Ramsey Colin(+) -

Welsh Government M4 Corridor Around Newport Environmental Statement Volume 1 Chapter 15: Community and Private Assets

Welsh Government M4 Corridor around Newport Environmental Statement Volume 1 Chapter 15: Community and Private Assets M4CAN-DJV-EGN-ZG_GEN-RP-EN-0022.docx At Issue | March 2016 CVJV/AAR 3rd Floor Longross Court, 47 Newport Road, Cardiff CF24 0AD Welsh Government M4 Corridor around Newport Environmental Statement Volume 1 Contents Page 15 Community and Private Assets 15-1 15.1 Introduction 15-1 15.2 Legislation and Policy Context 15-1 15.3 Assessment Methodology 15-3 15.4 Baseline Environment 15-11 15.5 Mitigation Measures Forming Part of the Scheme Design 15-44 15.6 Assessment of Potential Land Take Effects 15-45 15.7 Assessment of Potential Construction Effects 15-69 15.8 Assessment of Potential Operational Effects 15-97 15.9 Additional Mitigation and Monitoring 15-101 15.10 Assessment of Land Take Effects 15-104 15.11 Assessment of Construction Effects 15-105 15.12 Assessment of Operational Effects 15-111 15.13 Assessment of Cumulative Efects and Inter-related Effects 15-112 15.14 Summary of Effects 15-112 Welsh Government M4 Corridor around Newport Environmental Statement Volume 1 15 Community and Private Assets 15.1 Introduction 15.1.1 This chapter of the ES describes the assessment of effects on community and private assets resulting from the new section of motorway between Junction 23A at Magor and Junction 29 at Castleton, together with the Complementary Measures (including the reclassified section of the existing M4 between the same two junctions and the provision of improved facilities for pedestrians, cyclists and equestrians). This includes an assessment of effects on community facilities, including the following.