Christianity in Newport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SJ7 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

SJ7 bus time schedule & line map SJ7 Duffryn View In Website Mode The SJ7 bus line (Duffryn) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Duffryn: 7:55 AM (2) Glasllwch: 3:30 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest SJ7 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next SJ7 bus arriving. Direction: Duffryn SJ7 bus Time Schedule 10 stops Duffryn Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:55 AM Groves Road, Glasllwch Tuesday 7:55 AM Melbourne Way Turn, Glasllwch Wednesday 7:55 AM Quebec Close, Glasllwch Thursday 7:55 AM Toronto Close, Allt-Yr-Yn Community Friday 7:55 AM Junior School, Glasllwch Saturday Not Operational Enville Road, Ridgeway Ridgeway, Allt-Yr-Yn Community Redbrook Road, Ridgeway 46 Redbrook Road, Allt-Yr-Yn Community SJ7 bus Info Direction: Duffryn Sorrel Drive, Allt-Yr-Yn Stops: 10 Trip Duration: 35 min Barrack Hill, Crindau Line Summary: Groves Road, Glasllwch, Melbourne Malpas Road, Shaftesbury Community Way Turn, Glasllwch, Quebec Close, Glasllwch, Junior School, Glasllwch, Enville Road, Ridgeway, Redbrook Lyceum, Crindau Road, Ridgeway, Sorrel Drive, Allt-Yr-Yn, Barrack Hill, Crindau, Lyceum, Crindau, St Joseph`S Rc High St Joseph`S Rc High School, Duffryn School, Duffryn Direction: Glasllwch SJ7 bus Time Schedule 12 stops Glasllwch Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 3:30 PM St Joseph`S Rc High School, Duffryn Tuesday 3:30 PM Lyceum, Crindau Jewell Lane, Shaftesbury Community Wednesday 3:30 PM Prospect, Crindau Thursday 3:30 PM 47 Malpas Road, -

Download This Statement As A

Equitable Global Access to Covid-19 Vaccinations BMS World Mission, the Baptist Union of Great Britain, the Baptist Union of Wales and the Baptist Union of Scotland, together with the 241 member bodies of the Baptist World Alliance affirm that “in Jesus Christ all people are equal. We oppose all forms of racism, inequality and injustice and so will do all in our power to address and confront these sins.”1 We acknowledge the solidarity shared by millions of Baptists and non-Baptists alike in the face of the suffering caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. As we move into 2021, we also recognise our responsibility to participate in the solution to this crisis. We will do so by: • calling for the co-operation of governments to support co-ordinated mass vaccination systems and enhance access to vaccinations through aid and economic innovations. • urging Baptists, both in the UK and worldwide to participate in enabling global vaccination. • repudiating unhelpful narratives associated with mass vaccination and asking Baptists and all people of goodwill to do so as well. • issuing a clarion call for just access to Covid-19 vaccines globally – including five specific steps of justice necessary for equitable global access – and a shared solidarity in addressing this pandemic. Covid-19 has exposed inequality Inequality has been exposed in a multitude of ways during the Covid-19 pandemic. We have seen the lowest Human Development Index (HDI) countries struggle to address comprehensive testing and treatment of the virus, artificially masking its impact in many places.2 Stigma, failure to address other existing health concerns and economic regression have followed. -

Alway Profile 2019 Population

2019 Community Well-being Profile Alway Population Final July 2019 v1.0 Table of Contents Table of Contents Population ................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Overview ............................................................................................................................................................... 2 Population make up .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Population Density .............................................................................................................................................10 Population Changes ............................................................................................................................................11 Supporting Information ......................................................................................................................................13 Gaps ....................................................................................................................................................................15 Alway Community Well-being Profile - Population Page 1 Alway Population Population Overview Population 8,573 % of the Newport Population 5.66% Population Density 4,855.8 Ethnic Minority Population 10.6% (population per km2) Area (km2) 1.77 Lower Super Output Areas 6 % of Newport Area 0.93% -

“The Prophecies of Fferyll”: Virgilian Reception in Wales

“The Prophecies of Fferyll”: Virgilian Reception in Wales Revised from a paper given to the Virgil Society on 18 May 2013 Davies Whenever I make the short journey from my home to Swansea’s railway station, I pass two shops which remind me of Virgil. Both are chemist shops, both belong to large retail empires. The name-boards above their doors proclaim that each shop is not only a “pharmacy” but also a fferyllfa, literally “Virgil’s place”. In bilingual Wales homage is paid to the greatest of poets every time we collect a prescription! The Welsh words for a chemist or pharmacist fferyllydd( ), for pharmaceutical science (fferylliaeth), for a retort (fferyllwydr) are – like fferyllfa,the chemist’s shop – all derived from Fferyll, a learned form of Virgil’s name regularly used by writers and poets of the Middle Ages in Wales.1 For example, the 14th-century Dafydd ap Gwilym, in one of his love poems, pic- tures his beloved as an enchantress and the silver harp that she is imagined playing as o ffyrf gelfyddyd Fferyll (“shaped by Virgil’s mighty art”).2 This is, of course, the Virgil “of popular legend”, as Comparetti describes him: the Virgil of the Neapolitan tales narrated by Gervase of Tilbury and Conrad of Querfurt, Virgil the magician and alchemist, whose literary roots may be in Ecl. 8, a fascinating counterfoil to the prophet of the Christian interpretation of Ecl. 4.3 Not that the role of magician and the role of prophet were so differentiated in the medieval mind as they might be today. -

Religion and the Church in Geoffrey of Monmouth

Chapter 14 Religion and the Church in Geoffrey of Monmouth Barry Lewis Few authors inspire as many conflicting interpretations as Geoffrey of Monmouth. On one proposition, however, something close to a consen- sus reigns: Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote history in a manner that shows re- markable indifference toward religion and the institutional church. Antonia Gransden, in her fundamental survey of medieval English historical writing, says that “the tone of his work is predominantly secular” and even that he “abandoned the Christian intention of historical writing” and “had no moral, edificatory purpose”, while J.S.P. Tatlock, author of what is still the fullest study of Geoffrey, speaks of a “highly intelligent, rational and worldly personality” who shows “almost no interest in monachism … nor in miracles”, nor indeed in “religion, theology, saints, popes, even ecclesiastics in general”.1 Yet, even if these claims reflect a widely shared view, it is nonetheless startling that they should be made about a writer who lived in the first half of the 12th century. Some commentators find Geoffrey’s work so divergent from the norms of ear- lier medieval historiography that they are reluctant to treat him as a historian at all. Gransden flatly describes him as “a romance writer masquerading as an historian”.2 More cautiously, Matilda Bruckner names Geoffrey among those Latin historians who paved the way for romance by writing a secular-minded form of history “tending to pull away from the religious model (derived from Augustine and Orosius) that had viewed human history largely within the scheme of salvation”.3 This Christian tradition of historiography, against which Geoffrey of Monmouth is said to have rebelled, had its origins in late antiquity in the works of Eusebius, Augustine, and Orosius. -

Print Finishers

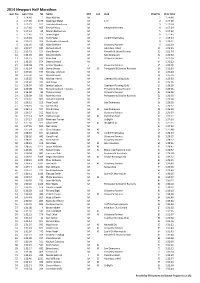

2014 Newport Half Marathon Gun Pos Gun Time No Name M/F Cat Club Chip Pos Chip Time 1 1:14:46 1 Ryan McFlyn M 1 1:14:46 2 1:17:09 1175 Matthew Welsh M 1 Tri 2 1:17:08 3 1:17:15 910 Leighton Rawlinson M 3 1:17:14 4 1:17:30 865 Emrys Penny M Newport Harriers 4 1:17:29 5 1:17:43 68 Maciej Bialogonski M 5 1:17:42 6 1:17:46 316 James Elgar M 6 1:17:45 7 1:19:35 372 Tom Foster M Cardiff Triathletes 7 1:19:34 8 1:20:33 926 Christopher Rennick M 8 1:20:31 9 1:21:10 425 Mike Griffiths M Lliswerry Runners 9 1:21:09 10 1:21:27 680 Richard Lloyd M Aberdare VAAC 10 1:21:25 11 1:21:52 117 Gary Brown M Penarth & Dinas Runners 11 1:21:50 12 1:22:03 801 Doug Nicholls M San Domenico 12 1:22:02 13 1:22:21 625 Alun King M Lliswerry Runners 13 1:22:18 14 1:22:25 574 Dean Johnson M 14 1:22:22 15 1:22:38 772 Emma Wookey F Lliswerry Runners 15 1:22:36 16 1:22:54 256 Steve Davies M 50 Pontypool & District Runners 16 1:22:52 17 1:25:26 575 Nicholas Johnson M 17 1:25:24 18 1:25:50 597 Richard Jones M 18 1:25:39 19 1:25:55 458 Michael Harris M Caerleon Running Club 19 1:25:53 20 1:26:02 163 Jack Casey M 20 1:25:56 21 1:26:07 162 James Casburn M Caerleon Running Club 22 1:26:05 22 1:26:08 541 Richard Jackson-Hookins M Penarth & Dinas Runners 23 1:26:06 23 1:26:09 82 Thomas Bland M Lliswerry Runners 24 1:26:06 24 1:26:09 531 Mark Hurford M Pontypool & District Runners 21 1:26:03 25 1:26:10 803 Daniel Oakenfull M 25 1:26:08 26 1:26:12 215 Pete Croall M San Domenico 26 1:26:10 27 1:26:15 57 Jon Belcher M 27 1:26:12 28 1:26:43 107 Phil Bristow M 50 San Domenico 28 1:26:40 -

73 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

73 bus time schedule & line map 73 Newport - Chepstow View In Website Mode The 73 bus line (Newport - Chepstow) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Chepstow: 7:05 AM - 6:00 PM (2) Newport: 8:05 AM - 6:05 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 73 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 73 bus arriving. Direction: Chepstow 73 bus Time Schedule 41 stops Chepstow Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:05 AM - 6:00 PM Friars Walk 11, Newport 1-7 Friars Walk Shopping Centre, Newport Tuesday 7:05 AM - 6:00 PM Cenotaph, Newport Wednesday 7:05 AM - 6:00 PM Clarence Place, Newport Thursday 7:05 AM - 6:00 PM Library, Maindee Friday 7:05 AM - 6:00 PM Maindee Square, Maindee Saturday 7:05 AM - 6:00 PM Chepstow Road, Newport Eveswell School, Maindee Walmer Road, Maindee 73 bus Info Direction: Chepstow Beechwood Park, Beechwood Stops: 41 422 Chepstow Road, Newport Trip Duration: 46 min Line Summary: Friars Walk 11, Newport, Cenotaph, Acacia Avenue, Somerton Newport, Library, Maindee, Maindee Square, 429 Chepstow Road, Alway Community Maindee, Eveswell School, Maindee, Walmer Road, Maindee, Beechwood Park, Beechwood, Acacia Farmwood Close, Lawrence Hill Avenue, Somerton, Farmwood Close, Lawrence Hill, 585 Chepstow Road, Alway Community Glanwern Grove, Bishpool, Man Of Gwent, Bishpool, Bishpool Lane, Bishpool, Royal Oak, Celtic Manor, Glanwern Grove, Bishpool Coldra, Taylors Cafe, Langstone, Cat`S Ash Road, 643 Chepstow Road, Alway Community Langstone, Grange, Langstone, New Inn, -

Coridor-Yr-M4-O-Amgylch-Casnewydd

PROSIECT CORIDOR YR M4 O AMGYLCH CASNEWYDD THE M4 CORRIDOR AROUND NEWPORT PROJECT Malpas Llandifog/ Twneli Caerllion/ Caerleon Llandevaud B Brynglas/ 4 A 2 3 NCN 4 4 Newidiadau Arfaethedig i 6 9 6 Brynglas 44 7 Drefniant Mynediad/ A N tunnels C Proposed Access Changes 48 N Pontymister A 4 (! M4 C25/ J25 6 0m M4 C24/ J24 M4 C26/ J26 2 p h 4 h (! (! p 0 Llanfarthin/ Sir Fynwy/ / 0m 4 u A th 6 70 M4 Llanmartin Monmouthshire ar m Pr sb d ph Ex ese Gorsaf y Ty-Du/ do ifie isti nn ild ss h ng ol i Rogerstone A la p M4 'w A i'w ec 0m to ild Station ol R 7 Sain Silian/ be do nn be Re sba Saint-y-brid/ e to St. Julians cla rth res 4 ss u/ St Brides P M 6 Underwood ifi 9 ed 4 ng 5 Ardal Gadwraeth B M ti 4 Netherwent 4 is 5 x B Llanfihangel Rogiet/ 9 E 7 Tanbont 1 23 Llanfihangel Rogiet B4 'St Brides Road' Tanbont Conservation Area t/ Underbridge en Gwasanaethau 'Rockfield Lane' w ow Gorsaf Casnewydd/ Trosbont -G st Underbridge as p Traffordd/ I G he Newport Station C 4 'Knollbury Lane' o N Motorway T Overbridge N C nol/ C N Services M4 C23/ sen N Cyngor Dinas Casnewydd M48 Pre 4 Llanwern J23/ M48 48 Wilcrick sting M 45 Exi B42 Newport City Council Darperir troedffordd/llwybr beiciau ar hyd Newport Road/ M4 C27/ J27 M4 C23A/ J23A Llanfihangel Casnewydd/ Footpath/ Cycleway Provided Along Newport Road (! Gorsaf Pheilffordd Cyffordd Twnnel Hafren/ A (! 468 Ty-Du/ Parcio a Theithio Arfaethedig Trosbont Rogiet/ Severn Tunnel Junction Railway Station Newport B4245 Grorsaf Llanwern/ Trefesgob/ 'Newport Road' Rogiet Rogerstone 4 Proposed Llanwern Overbridge -

JF3 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

JF3 bus time schedule & line map JF3 Clytha Park View In Website Mode The JF3 bus line (Clytha Park) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Clytha Park: 3:30 PM (2) Duffryn: 7:40 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest JF3 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next JF3 bus arriving. Direction: Clytha Park JF3 bus Time Schedule 32 stops Clytha Park Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 3:30 PM John Frost School , Duffryn Tuesday 3:30 PM Park Drive, Maesglas Cardiff Road, Newport Wednesday 3:30 PM Ebbw Bridge Club, Maesglas Thursday 3:30 PM Friday 3:30 PM Drinkwater Gardens, Gaer Saturday Not Operational Gear Baptist Church, Gaer Wells Close, Gaer Hardy Close, Newport JF3 bus Info Lamb Close, Gaer Direction: Clytha Park Scott Close, Newport Stops: 32 Trip Duration: 35 min Cowper Close, Gaer Line Summary: John Frost School , Duffryn, Park Collins Close, Newport Drive, Maesglas, Ebbw Bridge Club, Maesglas, Drinkwater Gardens, Gaer, Gear Baptist Church, Shakespeare Crescent, Gaer Gaer, Wells Close, Gaer, Lamb Close, Gaer, Cowper Close, Gaer, Shakespeare Crescent, Gaer, Hillside, Hillside, Gaer Gaer, Gaer Park Club, Stelvio Park, Post O∆ce, Stelvio Park, Cemetery Gates, Stelvio Park, West Park Gaer Park Club, Stelvio Park Road, Stelvio Park, St John the Baptist, Caerau Park, Coed Melyn Park, Caerau Park, Nant Coch Drive, Highƒeld Road, Gaer Community Glasllwch, Melbourne Way, Glasllwch, Glasllwch Post O∆ce, Stelvio Park Crescent, Glasllwch, Groves Road, Glasllwch, Melbourne Way -

Working Timetable

BOOK PF Private and not for publication WORKING TIMETABLE SUNDAY 13 DECEMBER 2015 to SATURDAY 14 MAY 2016 FREIGHT AND DEPARTMENTAL SERVICES Section PF11 AWRE AND PATCHWAY TO BRIDGEND PF11 - AWRE AND PATCHWAY TO BRIDGEND Mondays to Fridays 14 December to 13 May 12345678910111213141516 Signal ID 6V66 6V35 6B59 6V29 6V04 6V04 6V81 6V66 3Z23 6M77 6H30 6H30 0B59 3Z01 3Z33 6V97 Orig. Dep. Time 12.07 18.05 17.18 19.13 19.59 19.59 18.32 12.30 23.13 15.43 23.42 23.56 00.05 19.57 23.10 14.46 Orig. Loc. Name Redcar B.S.C. Masborough Exeter Beeston Sims Kingsbury Sdgs Kingsbury Sdgs Masborough Redcar B.S.C. Bristol Barton Cwmbargoed Llanwern Llanwern Cardiff Tidal T.C. Didcot T.C. Bristol Barton Beeston Sims Ore T. F.D. Alphington Road Mcintyre Ltd F.D. Ore T. Hill W.R.D. Opencast Colly. Exchange Sdgs Exchange Sdgs Hill W.R.D. Mcintyre Ltd Dest. Loc. Name Margam T.C. Margam T.C. Derby Hope (Earles Margam T.C. Margam T.C. Margam T.C. Derby Bristol Barton Cardiff Tidal T.C. R.T.C.(Network Sidings) Dbs R.T.C.(Network Hill W.R.D. Rail) Rail) Timing Load 60H66S22 60-TR40 60H66S16 60H66S16 60H66S16 60H66S16 60-66S22 60H66S22 UTU-R 60H66S18 60-66S08 60-66S08 LD75 UTU-R UTU-R 60H66S18 Operating Characteristics YQYY Y Y Q Q Dates Of Operation FSX TThO ThO FSX ThO WO MWO Sun ThO MO Sun FSX FO ThO ThO MO Awre dep 1 ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... mgn 2 .. -

Saint Alban and the Cult of Saints in Late Antique Britain

Saint Alban and the Cult of Saints in Late Antique Britain Michael Moises Garcia Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Institute for Medieval Studies August, 2010 ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Michael Moises Garcia to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. © 2010 The University of Leeds and Michael Moises Garcia iii Acknowledgements First and foremost, I must thank my amazing wife Kat, without whom I would not have been able to accomplish this work. I am also grateful to the rest of my family: my mother Peggy, and my sisters Jolie, Julie and Joelle. Their encouragement was invaluable. No less important was the support from my supervisors, Ian Wood, Richard Morris, and Mary Swan, as well as my advising tutor, Roger Martlew. They have demonstrated remarkable patience and provided assistance above and beyond the call of duty. Many of my colleagues at the University of Leeds provided generous aid throughout the past few years. Among them I must especially thcmk Thom Gobbitt, Lauren Moreau, Zsuzsanna Papp Reed, Alex Domingue, Meritxell Perez-Martinez, Erin Thomas Daily, Mark Tizzoni, and all denizens of the Le Patourel room, past and present. -

Community Activity and Groups Directory

Newport City Council Community Connector Service Directory of Activities Information correct at April 2017 This directory is intended as a local information resource only and Newport City Council neither recommend nor accept any liability for the running of independent support services. You are advised to contact organisations directly as times or locations may change. This directory is available on Newport City Council website: www.newport.gov.uk/communityconnectors 1 Section 1: Community Activities and Groups Page Art, Craft , Sewing and Knitting 3 Writing, Language and Learning 13 BME Groups 18 Card / Board Games and Quiz Nights 19 Computer Classes 21 Library and Reading Groups 22 Volunteering /Job Clubs 24 Special Interest and History 32 Animals and Outdoor 43 Bowls and Football 49 Pilates and Exercise 53 Martial Arts and Gentle Exercise 60 Exercise - Wellbeing 65 Swimming and Dancing 70 Music, Singing and Amateur Dramatics 74 Social Bingo 78 Social Breakfast, Coffee Morning and Lunch Clubs 81 Friendship and Social Clubs 86 Sensory Loss, LGBT and Female Groups 90 Additional Needs / Disability and Faith Groups 92 Sheltered Accommodation 104 Communities First and Transport 110 2 Category Activity Ward/Area Venue & Location Date & Time Brief Outline Contact Details Art Art Class Allt-Yr-Yn Ridgeway & Allt Yr Thursday 10am - Art Class Contact: 01633 774008 Yn Community 12pm Centre Art Art Club Lliswerry Lliswerry Baptist Monday 10am - A club of mixed abilities and open to Contact: Rev Geoff Bland Church, 12pm weekly all. Led by experienced tutors who 01633 661518 or Jenny Camperdown Road, can give you hints and tips to 01633 283123 Lliswerry, NP19 0JF improve your work.