Flying Dutchman)(1843) (1813–1883) Overture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mutiny Simplifies Deflector Plan

` ASX: MYG Mutiny Simplifies Deflector Plan 4 August 2014 Highlights: • New management complete “Mine Operators Review” of the Deflector 2013 Definitive Feasibility Study, simplifying and optimising the Deflector Project • Mutiny Board has resolved to pursue financing and development of the Deflector project based on the new mine plan • New mine plan reduces open pit volume by 80% based on both rock properties and ore thickness, and establishes early access to the underground mine • Processing capital and throughput revised to align with optimal underground production rate of 380,000 tonnes per annum • Payable metal of 365,000 gold ounces, 325,000 silver ounces, and 15,000 copper tonnes • Pre-production capital of $67.6M • C1 cash cost of $549 per gold ounce • All in sustaining cost of $723 per gold ounce • Exploration review completed with primary focus to be placed on the 7km long, under explored, “Deflector Corridor” Note: Payable metal and costs presented in the highlights are taken from the Life of Mine Inventory model (LOM Inventory). All currency in AUS$ unless marked. Mutiny Gold Ltd (ASX:MYG) (“Mutiny” or “The Company”) is pleased to announce that the new company management, under the leadership of Managing Director Tony James, has completed an internal “Mine Operators Review” of the Deflector gold, copper and silver project, located within the Murchison Region of Western Australia. The review was undertaken on detail associated with the 2013 Definitive Feasibility Study (DFS) (ASX announcement 2 September, 2013). Tony James, -

Creativity & Innovation

MISSOURI MUSIC EDUCATORS 78TH ANNuaL IN-SERVICE WORKSHOP/CONFERENce CREATIVITY & INNOVATION JANUARY 27- 30, 2016 TAN-TAR-A RESORT & GOLF CLUB LAKE OZARK, MISSOURI 1 probably a tan tar a ad here? or nafme something or other 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS From the President .................................................................................4 Conference Schedule Wednesday ............................................................................................5 Thursday .................................................................................................7 All State Rehearsal Schedule ............................................................... 17 Friday .................................................................................................. 22 Saturday .............................................................................................. 37 All-State Concert Programs .................................................................. 40 Leadership MMEA Board of Directors/Administrative Personnel ............................44 MMEA Advisory Council .......................................................................45 District Leadership ...............................................................................46 Affiliate Organizations .........................................................................49 Supporting Organizations ...................................................................50 Schedule of Organization Business Meetings .....................................51 MMEA Past -

Treble Voices in Choral Music

loft is shown by the absence of the con• gregation: Bach and Maria Barbara were Treble Voices In Choral Music: only practicing and church was not even in session! WOMEN, MEN, BOYS, OR CASTRATI? There were certain places where wo• men were allowed to perform reltgious TIMOTHY MOUNT in a "Gloria" and "Credo" by Guillaume music: these were the convents, cloisters, Legrant in 1426. Giant choir books, large and religious schools for girls. Nuns were 2147 South Mallul, #5 enough for an entire chorus to see, were permitted to sing choral music (obvious• Anaheim, California 92802 first made in Italy in the middle and the ly, for high voices only) among them• second half of the 15th century. In selves and even for invited audiences. England, choral music began about 1430 This practice was established in the with the English polyphonic carol. Middle Ages when the music was limited Born in Princeton, New Jersey, Timo• to plainsong. Later, however, polyphonic thy Mount recently received his MA in Polyphonic choral music took its works were also performed. __ On his musi• choral conducting at California State cue from and developed out of the cal tour of Italy in 1770 Burney describes University, Fullerton, where he was a stu• Gregorian unison chorus; this ex• several conservatorios or music schools dent of Howard Swan. Undergraduate plains why the first choral music in Venice for girls. These schools must work was at the University of Michigan. occurs in the church and why secular not be confused with the vocational con• compositions are slow in taking up He has sung professionally with the opera servatories of today. -

A Midsummer Night's Dream

9 TEATRO MASSIMO BRITTEN BENJAMIN B enjamin B ritten A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM | MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM NIGHT’S MIDSUMMER Membro di seguici su: teatromassimo.it Piazza Verdi - 90138 Palermo ISBN: 978-88-98389-61-2 euro 10,00 SOCI FONDATORI PARTNER PRIVATI REGIONE SICILIANA ASSESSORATO AL TURISMO SPORT E SPETTACOLI ALBO DEI DONATORI Fondazione ART BONUS Teatro Massimo Tasca d’Almerita Francesco Giambrone Sovrintendente Angelo Morettino srl CONSIGLIO DI INDIRIZZO Leoluca Orlando (sindaco di Palermo) Presidente Giovanni Alongi Leonardo Di Franco Vicepresidente Daniele Ficola Sais Autolinee Francesco Giambrone Sovrintendente Enrico Maccarone Agostino Randazzo Anna Sica Marco Di Marco COLLEGIO DEI REVISORI Maurizio Graffeo Presidente Filippone Assicurazione Marco Piepoli Gianpiero Tulelli Giuseppe Di Pasquale Alessandra Giurintano Di Marco TURNI A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM (Sogno di una notte di mezza estate) Opera in tre atti Libretto di Benjamin Britten e Peter Pears da A Midsummer Night’s Dream di William Shakespeare Data Turno Ora Musica di Benjamin Britten Martedì 19 settembre Prime 20.30 C Giovedì 21 settembre 18.30 Prima rappresentazione: F Venerdì 22 settembre 20.30 Aldeburgh Festival, 11 giugno 1960 Domenica 24 settembre D 17.30 Martedì 26 settembre B 18.30 S1 Mercoledì 27 settembre 18.30 Prima rappresentazione a Palermo Lo spettacolo sarà trasmesso in diretta da RAI Radio3 e in differita da RAI5 Allestimento del Palau de les Arts Reina Sofia di Valencia INDICE 1 ARGOMENTO 13 SYNOPSIS 17 ARGUMENT 21 HANDLUNG 25 2 ALESSANDRA SCIORTINO INTRODUZIONE ALL’OPERA 31 DARIO OLIVERI «SIGNORE, CHE PAZZI QUESTI MORTALI!» UN PERCORSO INTORNO AL MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM DI BENJAMIN BRITTEN 39 3 IL LIBRETTO 65 ATTO I 66 ATTO II 96 ATTO III 140 4 BENJAMIN BRITTEN 179 LE PRIME DI BRITTEN AL TEATRO MASSIMO 183 BIBLIOGRAFIA ESSENZIALE 191 NOTE BIOGRAFICHE 193 1 ARGOMENTO 13 SYNOPSIS 17 ARGUMENT 21 HANDLUNG 25 ARGOMENTO Sogno di una notte di mezza estate ATTO I Nel bosco Puck annuncia l’arrivo di Oberon e Titania. -

Ctspubs Brochure Nov 2005

THE MUSIC OF CLAUDE T. SMITH CONCERT BAND WORKS ENJOY A CD RECORDING CTS = Claude T. Smith Publications WJ = Wingert-Jones HL = Hal Leonard TITLE GRADE PUBLISHER TITLE GRADE PUBLISHER $1 OF THE MUSIC OF 7.95 each Acclamation..............................................................5 ..............Kalmus Intrada: Adoration and Praise ..................................4 ................CTS All 6 for Across the Wide Missouri (Concert Band) ................3..................WJ Introduction and Caccia............................................3 ................CTS $60 Affirmation and Credo ..............................................4 ................CTS Introduction and Fugato............................................3 ................CTS Claude T. Smith Allegheny Portrait ....................................................4 ................CTS Invocation and Jubiloso ............................................2 ..................HL Allegro and Intermezzo Overture ..............................3 ................CTS Island Fiesta ............................................................3 ................CTS America the Beautiful ..............................................2 ................CTS Joyance....................................................................5..................WJ CLAUDE T. SMITH: CLAUDE T. SMITH: American Folk Trilogy ..............................................3 ................CTS Jubilant Prelude ......................................................4 ..................HL A SYMPHONIC PORTRAIT -

Classics 3: Program Notes Overture to Candide Leonard Bernstein Born in Lawrence, Massachusetts, August 25, 1918

Classics 3: Program Notes Overture to Candide Leonard Bernstein Born in Lawrence, Massachusetts, August 25, 1918; died in New York, October 14, 1990 After collaborating on The Lark, a play with incidental music about Joan of Arc, Leonard Bernstein and Lillian Hellman turned their attention in 1954 to Voltaire’s novella Candide. They thought it the perfect vehicle to make an artistic statement against political intolerance in American society, just as Voltaire had done in eighteenth-century France. After bringing in poet Richard Wilbur to write the lyrics, they worked intermittently on Candide for two years. Enormous amounts of money were spent on the production, which opened in Boston on October 29, 1956. Though many critics called it brilliant, the production failed financially; after moving to New York in December, it was shut down after just seventy-three performances. Everyone had someone to blame, but many thought it failed because of audience confusion about its hybrid nature—was it an opera, operetta, or a musical? Leonard Bernstein: celebrating his The story revolves around the illegitimate Candide, who centennial loves and is loved in return by Cunegonde, daughter of nobility. They are plagued by myriad disasters, which lead them from Westphalia to Lisbon, Paris, Cadiz, Buenos Aires, Eldorado, Surinam, and finally Venice, where they are united at last. Bernstein’s often witty, sometimes tender music has been considered the work’s greatest asset, both in the initial failed production and in later successful versions. The Overture, possibly Bernstein’s most frequently performed piece, perfectly captures the mockery and satire as well as the occasional introspective moment of Voltaire’s masterful creation. -

La Donna Del Lago , the Met's First Production of the Bel Canto Showcase, on Great Performances at the Met

Press Contacts: Harry Forbes, WNET 212-560-8027 or [email protected] Eva Chien 212-870-4589 or [email protected] Press materials: http://pressroom.pbs.org or http://www.thirteen.org/13pressroom Website: http://www.pbs.org/wnet/gperf Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/GreatPerformances Twitter: @GPerfPBS Joyce DiDonato and Juan Diego Flórez Star In Rossini's La Donna del Lago , the Met's First Production of the Bel Canto Showcase, on Great Performances at the Met Sunday, August 2 at 12 p.m. on PBS Joyce DiDonato and Juan Diego Flórez headline Rossini's bel canto tour-de-force La Donna del Lago on THIRTEEN’S Great Performances at the Met Sunday, August 2 at 12 p.m. on PBS. (Check local listings.) In this Rossini classic based on the work by Sir Walter Scott, DiDonato sings the title role of Elena, the lady of the lake pursued by two men, with Flórez in the role of Giacomo, the benevolent king of Scotland. Michele Mariotti , last featured in the Great Performance at the Met broadcast of Rigoletto , conducts debuting Scottish director Paul Curran's staging, a co-production with Santa Fe Opera. The cast also includes Daniela Barcellona in the trouser role of Malcolm, John Osborn as Rodrigo, and Oren Gradus as Duglas. "The wondrous Ms. DiDonato and Mr. Mariotti, the fast-rising young Italian conductor, seemed almost in competition to see who could make music with more delicacy,” noted The New York Times earlier this year, and “Mr. Mariotti drew hushed gentle and transparent playing from the inspired Met orchestra.” And NY Classical Review raved, "Joyce DiDonato…was beyond perfect.. -

2018–2019 Annual Report

18|19 Annual Report Contents 2 62 From the Chairman of the Board Ensemble Connect 4 66 From the Executive and Artistic Director Digital Initiatives 6 68 Board of Trustees Donors 8 96 2018–2019 Concert Season Treasurer’s Review 36 97 Carnegie Hall Citywide Consolidated Balance Sheet 38 98 Map of Carnegie Hall Programs Administrative Staff Photos: Harding by Fadi Kheir, (front cover) 40 101 Weill Music Institute Music Ambassadors Live from Here 56 Front cover photo: Béla Fleck, Edgar Meyer, by Stephanie Berger. Stephanie by Chris “Critter” Eldridge, and Chris Thile National Youth Ensembles in Live from Here March 9 Daniel Harding and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra February 14 From the Chairman of the Board Dear Friends, In the 12 months since the last publication of this annual report, we have mourned the passing, but equally importantly, celebrated the lives of six beloved trustees who served Carnegie Hall over the years with the utmost grace, dedication, and It is my great pleasure to share with you Carnegie Hall’s 2018–2019 Annual Report. distinction. Last spring, we lost Charles M. Rosenthal, Senior Managing Director at First Manhattan and a longtime advocate of These pages detail the historic work that has been made possible by your support, Carnegie Hall. Charles was elected to the board in 2012, sharing his considerable financial expertise and bringing a deep love and further emphasize the extraordinary progress made by this institution to of music and an unstinting commitment to helping the aspiring young musicians of Ensemble Connect realize their potential. extend the reach of our artistic, education, and social impact programs far beyond In August 2019, Kenneth J. -

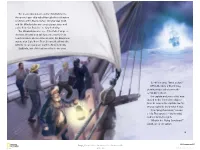

“What Is That?” Off in the Dark, a Frightening, Glowing Shape Sailed Across the Ocean Like a Ghost

The moon shined down on the Windcatcher as the great clipper ship sailed through the cold waters of the southern Pacific Ocean. The year was 1849, and the Windcatcher was carrying passengers and cargo from San Francisco to New York City. The Windcatcher was one of the fastest ships on the seas. She was now sailing south, near Chile in South America. She would soon enter the dangerous waters near Cape Horn. Then she would sail into the Atlantic Ocean and move north to New York City. Suddenly, one of the sailors yelled to the crew. “Look!” he cried. “What is that?” Off in the dark, a frightening, glowing shape sailed across the ocean like a ghost. The captain and some of his men moved to the front of the ship to look. As soon as the captain saw the strange sight, he knew what it was. “The Flying Dutchman,” he said softly. The captain looked worried and lost in his thoughts. “What is the Flying Dutchman?” asked one of the sailors. 2 3 Pirates often captured the ships when the crew resisted, they Facts about Pirates and stole the cargo without were sometimes killed or left violence. Often, just seeing at sea with little food or water. the pirates’ flag and hearing Other times, the pirates took A pirate is a robber at sea who great deal of valuable cargo their cannons was enough to the crew as slaves, or the crew steals from other ships out being shipped across the make the crew of these ships became pirates themselves! at sea. -

KING FM SEATTLE OPERA CHANNEL Featured Full-Length Operas

KING FM SEATTLE OPERA CHANNEL Featured Full-Length Operas GEORGES BIZET EMI 63633 Carmen Maria Stuarda Paris Opera National Theatre Orchestra; René Bologna Community Theater Orchestra and Duclos Chorus; Jean Pesneaud Childrens Chorus Chorus Georges Prêtre, conductor Richard Bonynge, conductor Maria Callas as Carmen (soprano) Joan Sutherland as Maria Stuarda (soprano) Nicolai Gedda as Don José (tenor) Luciano Pavarotti as Roberto the Earl of Andréa Guiot as Micaëla (soprano) Leicester (tenor) Robert Massard as Escamillo (baritone) Roger Soyer as Giorgio Tolbot (bass) James Morris as Guglielmo Cecil (baritone) EMI 54368 Margreta Elkins as Anna Kennedy (mezzo- GAETANO DONIZETTI soprano) Huguette Tourangeau as Queen Elizabeth Anna Bolena (soprano) London Symphony Orchestra; John Alldis Choir Julius Rudel, conductor DECCA 425 410 Beverly Sills as Anne Boleyn (soprano) Roberto Devereux Paul Plishka as Henry VIII (bass) Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Ambrosian Shirley Verrett as Jane Seymour (mezzo- Opera Chorus soprano) Charles Mackerras, conductor Robert Lloyd as Lord Rochefort (bass) Beverly Sills as Queen Elizabeth (soprano) Stuart Burrows as Lord Percy (tenor) Robert Ilosfalvy as roberto Devereux, the Earl of Patricia Kern as Smeaton (contralto) Essex (tenor) Robert Tear as Harvey (tenor) Peter Glossop as the Duke of Nottingham BRILLIANT 93924 (baritone) Beverly Wolff as Sara, the Duchess of Lucia di Lammermoor Nottingham (mezzo-soprano) RIAS Symphony Orchestra and Chorus of La Scala Theater Milan DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 465 964 Herbert von -

Media Release

Media Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: January 15, 2019 Contact: Edward Wilensky (619) 232-7636 [email protected] San Diego Opera’s 2018-2019 Main Stage Season Closes With Bizet’s Carmen Mezzo-soprano Ginger Costa-Jackson makes Company debut in signature role of Carmen Tenor Robert Watson sings Don José New production to San Diego Opera audiences San Diego, CA – Georges Bizet’s opera Carmen will close the 2018-2019 mainstage season. Carmen opens on Saturday, March 30, 2019 for four performances at the Civic Theatre. Additional performances are April 2, 5, and 7 (matinee), 2019. Bringing her signature role to San Diego Opera for her house debut is mezzo-soprano Ginger Costa-Jackson. The Los Angeles Times’ critic Mark Swed noted “Ginger Costa-Jackson, an exceptional young Sicilian American mezzo-soprano, brought a dangerous, animalistic vibrancy to the title role. There is a lusty yet somber quality to her strikingly dark mezzo, the ideal voice for Carmen.” She is joined by tenor Robert Watson, also in a Company debut, as Don José. Also in Company debuts are soprano Sarah Tucker as Micaëla and baritone Scott Conner as Escamillo. Rounding out the cast is bass Patrick Blackwell in his Company debut as Zuniga, soprano Tasha Koontz as Frasquita, mezzo-soprano Guadalupe Paz as Mercedes in her Company debut, tenor Felipe Prado in his house debut as Remendado, baritone Bernardo Bermudez as Dancairo, and baritone Brian Vu in a Company debut as Morales. Maestro Yves Abel, last heard conducting 2016’s Madama Butterfly, returns to lead these performances, and Kyle Lang, who made his directorial debut with 2017’s As One, returns to stage the action. -

The George London Foundation for Singers Announces Its 2016-17 Season of Events

Contact: Jennifer Wada Communications 718-855-7101 [email protected] www.wadacommunications.com THE GEORGE LONDON FOUNDATION FOR SINGERS ANNOUNCES ITS 2016-17 SEASON OF EVENTS: • THE RECITAL SERIES: ISABEL LEONARD & JARED BYBEE PAUL APPLEBY & SARAH MESKO AMBER WAGNER & REGINALD SMITH, JR. • THE 46TH ANNUAL GEORGE LONDON FOUNDATION AWARDS COMPETITION “This prestigious competition … now in its 45th year, can rightfully claim to act as a springboard for major careers in opera.” -The New York Times, February 18, 2016 Isabel Leonard, Jared Bybee, Paul Appleby, Sarah Mesko, Amber Wagner, Reginald Smith, Jr. (Download photos.) The George London Foundation for Singers has been honoring, supporting, and presenting the finest young opera singers in the U.S. and Canada since 1971. Upon the conclusion of the 20th year of its celebrated recital series, which was marked with a gala in April featuring some of opera’s most prominent American and Canadian stars, the Foundation announces its 2016-17 season of events: The George London Foundation Recital Series, which presents pairs of outstanding opera singers, many of whom were winners of a George London Award (the prize of the foundation’s annual vocal competition): George London Foundation for Singers Announces Its 2016-17 Season - Page 2 of 5 • Isabel Leonard, mezzo-soprano, and Jared Bybee, baritone. Mr. Bybee won an Encouragement Award at the 2016 competition. Sunday, October 9, 2016, at 4:00 pm • Paul Appleby, tenor, and Sarah Mesko, mezzo-soprano. Mr. Appleby won his George London Award in 2011, and Ms. Mesko won hers in 2015. Sunday, March 5, 2017, at 4:00 pm • Amber Wagner, soprano, and Reginald Smith, Jr., baritone.