Classics 3: Program Notes Overture to Candide Leonard Bernstein Born in Lawrence, Massachusetts, August 25, 1918

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overture to Candide Leonard Bernstein Did You Know?

nothing good about them, like violence, Did You Know? shipwrecks, or the Spanish Inquisition. • Less than two months before Candide’s In its initial Broadway run, in 1956–57, Broadway opening, Bernstein was named Candide played for 73 performances — Co-Principal Conductor of the New York hardly a stunning success — and Bernstein Philharmonic, alongside Dimitri Mitropoulos. would go on to alter the piece, again and • The Overture was heard in the Philharmon- again, for later revivals. Through all of ic’s historic 2008 performance in North Ko- the show’s transformations, the rollicking rea, when it was played without a conduc- Overture remained essentially untouched. tor, a tradition first adopted in tribute to Bernstein after his death. Born in Brooklyn, Aaron Copland polished his composing technique in France but and neighborly friendship. This expanse has returned home to establish what became found more success than the opera overall, recognized as a profoundly American sound, and it is often performed in a choral setting a musical language rich in folk inflections the composer prepared, with multiple voices and wide-open harmonies that proved irre- rendering each line. sistible to imitators. Copland’s Rodeo was also a stage work — His 1953 opera The Tender Land is a fine a ballet choreographed by Agnes de Mille, example of the lyrical aspect of Copland’s who said: Americana. Set in the 1930s, it tells the tale of Laurie, a teenager who is about to graduate It is not an epic, or the story of pioneer con- from high school and yearns for experiences quest. -

Ctspubs Brochure Nov 2005

THE MUSIC OF CLAUDE T. SMITH CONCERT BAND WORKS ENJOY A CD RECORDING CTS = Claude T. Smith Publications WJ = Wingert-Jones HL = Hal Leonard TITLE GRADE PUBLISHER TITLE GRADE PUBLISHER $1 OF THE MUSIC OF 7.95 each Acclamation..............................................................5 ..............Kalmus Intrada: Adoration and Praise ..................................4 ................CTS All 6 for Across the Wide Missouri (Concert Band) ................3..................WJ Introduction and Caccia............................................3 ................CTS $60 Affirmation and Credo ..............................................4 ................CTS Introduction and Fugato............................................3 ................CTS Claude T. Smith Allegheny Portrait ....................................................4 ................CTS Invocation and Jubiloso ............................................2 ..................HL Allegro and Intermezzo Overture ..............................3 ................CTS Island Fiesta ............................................................3 ................CTS America the Beautiful ..............................................2 ................CTS Joyance....................................................................5..................WJ CLAUDE T. SMITH: CLAUDE T. SMITH: American Folk Trilogy ..............................................3 ................CTS Jubilant Prelude ......................................................4 ..................HL A SYMPHONIC PORTRAIT -

Jerold Frederic Presents Concert of Gripping Music Philharmonic

THE% ECHO VOL. XXV TAYLOR UNIVERSITY, UPLAND, INDIANA, SATURDAY. FEBRUARY 5, 1938 NO. 9 Judge Fred Bale Jerold Frederic Mystery Abounds Philharmonic Orchestra Coming Discusses Vital Presents Concert When Dramatists Issues at T. U. Of Gripping Music Thrill Audience All Taylor music lovers were A phantom tiger, a death light, thrilled at the masterful playing a haunted house, a terrific storm of Jehold Frederic as he was pre — an ideal setting for a mystery! sented by the Lyceum Committee, In Spiers Hall on January 29th Tuesday evening, January 18th, one of the hit programs of the in Shreiner Auditorium. year was the presentation of His graduation from the "Tiger House", Robert St. Clair's thundering londs to the soft, popular three act. novel comedy. sweet passages, his brilliant tech In the minds of the audience nique, excellent tone quality and which crowded the little audi keen sense of rhythm held the torium to its capacity, the play audience enthralled during the | ranks high among Taylor's Magic of Murdock G. H. Shapiro and entire program. His powerful, literary productions. No one was His Orchestra to yet gentle fingers brought forth disappointed in the thrilling en Provides Thrills his notable creative ability in his tertainment. Appear at Taylor interpretation of Chopin. His Weird fantastical sounds, For Large Group presentation of Liszt himself, tricky movable panels, cruel On February 19, the Lyceum rather than his music, it was as | clutching claws! Was it any Even the "front" seats of Committee is presenting the next if his listeners were for the time wonder onlookers sat on the Shreiner Auditorium were oc in the series of programs. -

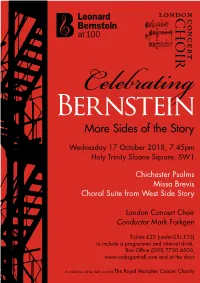

Bernsteincelebrating More Sides of the Story

BernsteinCelebrating More Sides of the Story Wednesday 17 October 2018, 7.45pm Holy Trinity Sloane Square, SW1 Chichester Psalms Missa Brevis Choral Suite from West Side Story London Concert Choir Conductor Mark Forkgen Tickets £25 (under-25s £15) to include a programme and interval drink. Box Office (020) 7730 4500, www.cadoganhall.com and at the door A collection will be held in aid of The Royal Marsden Cancer Charity One of the most talented and successful musicians in American history, Leonard Bernstein was not only a composer, but also a conductor, pianist, educator and humanitarian. His versatility as a composer is brilliantly illustrated in this concert to celebrate the centenary of his birth. The Dean of Chichester commissioned the Psalms for the 1965 Southern Cathedrals Festival with the request that the music should contain ‘a hint of West Side Story.’ Bernstein himself described the piece as ‘forthright, songful, rhythmic, youthful.’ Performed in Hebrew and drawing on jazz rhythms and harmonies, the Psalms Music Director: include an exuberant setting of ‘O be joyful In the Lord all Mark Forkgen ye lands’ (Psalm 100) and a gentle Psalm 23, ‘The Lord is my shepherd’, as well as some menacing material cut Nathan Mercieca from the score of the musical. countertenor In 1988 Bernstein revisited the incidental music in Richard Pearce medieval style that he had composed in 1955 for organ The Lark, Anouilh’s play about Joan of Arc, and developed it into the vibrant Missa Brevis for unaccompanied choir, countertenor soloist and percussion. Anneke Hodnett harp After three contrasting solo songs, the concert is rounded off with a selection of favourite numbers from Sacha Johnson and West Side Story, including Tonight, Maria, I Feel Pretty, Alistair Marshallsay America and Somewhere. -

ARSC Journal

LEONARD BERNSTEIN, A COMPOSER DISCOGRAPHY" Compiled by J. F. Weber Sonata for clarinet and piano (1941-42; first performed 4-21-42) David Oppenheim, Leonard Bernstein (recorded 1945) (78: Hargail set MW 501, 3ss.) Herbert Tichman, Ruth Budnevich (rec. c.1953} Concert Hall Limited Editions H 18 William Willett, James Staples (timing, 9:35) Mark MRS 32638 (released 12-70, Schwann) Stanley Drucker, Leonid Hambro (rec. 4-70) (10:54) Odyssey Y 30492 (rel. 5-71) (7) Anniversaries (for piano) (1942-43) (2,5,7) Leonard Bernstein (o.v.) (rec. 1945) (78: Hargail set MW 501, ls.) (1,2,3) Leonard Bernstein (rec. c.1949) (4:57) (78: RCA Victor 12 0683 in set DM 1278, ls.) Camden CAL 214 (rel. 5-55, del. 2-58) (4,5) Leonard Bernstein (rec. c.1949) (3:32) (78: RCA Victor 12 0228 in set DM 1209, ls.) (vinyl 78: RCA Victor 18 0114 in set DV 15, ls.) Camden CAL 214 (rel. 5-55, del. 2-58); CAL 351 (6,7) Leonard Bernstein (rec. c.1949) (2:18) Camden CAL 214 (rel. 5-55, del. 2-58); CAL 351 Jeremiah symphony (1941-44; f.p. 1-28-44) Nan Merriman, St. Louis SO--Leonard Bernstein (rec. 12-1-45) ( 23: 30) (78: RCA Victor 11 8971-3 in set DM 1026, 6ss.) Camden CAL 196 (rel. 2-55, del. 6-60) "Single songs from tpe Broadway shows and arrangements for band, piano, etc., are omitted. Thanks to Jane Friedmann, CBS; Peter Dellheim, RCA; Paul de Rueck, Amberson Productions; George Sponhaltz, Capitol; James Smart, Library of Congress; Richard Warren, Jr., Yael Historical Sound Recordings; Derek Lewis, BBC. -

LA CAGE AUX FOLLES ‘The Best of Times Is Now’ As the ESL Federal Credit Union 2019-2020 Season Kicks Off with One of Musical Theatre’S Biggest All-Time Hits

Media Contact: Dawn Kellogg Communications Manager (585) 420-2059 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE GEVA’S 47TH SEASON BEGINS WITH LA CAGE AUX FOLLES ‘The Best of Times is Now’ as the ESL Federal Credit Union 2019-2020 Season kicks off with one of musical theatre’s biggest all-time hits. La Cage aux Folles is the first musical to win Tony Awards for Best Revival of a Musical twice and was the inspiration for the 1996 hit film, The Birdcage. To celebrate his 25th Anniversary as Artistic Director, Mark Cuddy will star as nightclub owner Georges. Rochester, N.Y., August 14, 2019 – Geva Theatre Center presents La Cage Aux Folles, with book by Harvey Fierstein, music and lyrics by Jerry Herman, based on the play by Jean Poiret, directed by Melissa Rain Anderson, with musical direction by Don Kot, and choreography by Sam Hay in the Elaine P. Wilson Stage from September 3 through October 6. In sunny St. Tropez, Georges and Albin run a glamorous nightclub with fabulous drag performers. Their blissful existence is turned upside down when Georges’ son announces that he is getting married…to the daughter of one of France’s most conservative politicians. Georges and Albin do their best to ensure that the marriage goes off without a hitch, with hilarious results. One of musical theatre’s biggest all-time hits, La Cage aux Folles features an exuberant score by Jerry Herman (Mame; Hello, Dolly!). Winner of six Tony Awards including “Best Musical” when it premiered in 1983, both the 2004 and 2010 Broadway revivals won the Tony Award for “Best Revival of a Musical.” La Cage aux Folles was the inspiration for the 1996 hit film The Birdcage. -

PROGRAM NOTES Ludwig Van Beethoven Overture to Fidelio

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Ludwig van Beethoven Born December 16, 1770, Bonn, Germany. Died March 26, 1827, Vienna, Austria. Overture to Fidelio Beethoven began to compose Fidelio in 1804, and he completed the score the following year. The first performance was given on November 20, 1805, at the Theater an der Wien in Vienna. Beethoven revised the score in preparation for a revival that opened there on March 29, 1806. For a new production in 1814, he made substantial revisions and wrote the overture performed at these concerts. The overture wasn’t ready in time for the premiere on May 23, 1814, in Vienna’s Kärntnertor Theater, but it was played at the second performance. The overture calls for an orchestra consisting of two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, two trombones, timpani, and strings. Performance time is approximately six minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Beethoven’s Overture to Fidelio were given at the Auditorium Theatre on December 14 and 15, 1894, with Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances of the overture (and the complete opera) were given at Orchestra Hall on May 26, 28, and 31, 1998, with Daniel Barenboim conducting. The Orchestra first performed this overture at the Ravinia Festival on July 16, 1938, with Willem van Hoogstraten conducting, and most recently on July 30, 2008, with Sir Andrew Davis conducting. Nothing else in Beethoven’s career caused as much effort and heartbreak as the composition of his only opera, which took ten years, inspired four different overtures, and underwent two major revisions and a name change before convincing Beethoven that he was not a man of the theater. -

Composition Catalog

1 LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 New York Content & Review Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. Marie Carter Table of Contents 229 West 28th St, 11th Floor Trudy Chan New York, NY 10001 Patrick Gullo 2 A Welcoming USA Steven Lankenau +1 (212) 358-5300 4 Introduction (English) [email protected] Introduction 8 Introduction (Español) www.boosey.com Carol J. Oja 11 Introduction (Deutsch) The Leonard Bernstein Office, Inc. Translations 14 A Leonard Bernstein Timeline 121 West 27th St, Suite 1104 Straker Translations New York, NY 10001 Jens Luckwaldt 16 Orchestras Conducted by Bernstein USA Dr. Kerstin Schüssler-Bach 18 Abbreviations +1 (212) 315-0640 Sebastián Zubieta [email protected] 21 Works www.leonardbernstein.com Art Direction & Design 22 Stage Kristin Spix Design 36 Ballet London Iris A. Brown Design Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Limited 36 Full Orchestra Aldwych House Printing & Packaging 38 Solo Instrument(s) & Orchestra 71-91 Aldwych UNIMAC Graphics London, WC2B 4HN 40 Voice(s) & Orchestra UK Cover Photograph 42 Ensemble & Chamber without Voice(s) +44 (20) 7054 7200 Alfred Eisenstaedt [email protected] 43 Ensemble & Chamber with Voice(s) www.boosey.com Special thanks to The Leonard Bernstein 45 Chorus & Orchestra Office, The Craig Urquhart Office, and the Berlin Library of Congress 46 Piano(s) Boosey & Hawkes • Bote & Bock GmbH 46 Band Lützowufer 26 The “g-clef in letter B” logo is a trademark of 47 Songs in a Theatrical Style 10787 Berlin Amberson Holdings LLC. Deutschland 47 Songs Written for Shows +49 (30) 2500 13-0 2015 & © Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. 48 Vocal [email protected] www.boosey.de 48 Choral 49 Instrumental 50 Chronological List of Compositions 52 CD Track Listing LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 2 3 LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 A Welcoming Leonard Bernstein’s essential approach to music was one of celebration; it was about making the most of all that was beautiful in sound. -

Program Notes

Program Notes Program Notes by April L. Racana Wed. October 19 The 105th Tokyo Opera City Subscription Concert 10 19 Macbeth was Verdi’s tenth opera, years in developing Italian opera. The Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) composed originally in 1847, and revised effectiveness of these sonorities to Opera“Luisa Miller” Overture (Ca. 6min) significantly in 1865. Based on the convey the heights and depths of each Shakespeare play, the composer worked of the character’s emotions as well as Ballet Music from Opera“Macbeth” (ca. 12 min) closely with Francesco Maria Piave (and set the stage for his operas and draw the later Andrea Maffei) to create the libretto. audience into each scene is a testament Verdi has been quoted as saying that the to the talents of Verdi’s writing. In Giuseppe Verdi is known as one of becomes a victim of her male love- bard was “one of my very special poets, addition, they have withstood the test of the primary figures contributing to the interest, who she knows as Carlo, but and I have had him in my hands from time with audiences, even though the development of Italian opera during the who is really Rodolfo, the son of a local earliest youth, and I read and re-read him operas themselves have, at times, had time when Italian nationalism was on the count. Rodolfo, in turn loves her, but continually.” So much so that he would limited performances. rise. By the time La Traviata was staged is tricked into poisoning both her and go on to compose two more operas based in 1853, Verdi had already composed himself. -

Voltaire's Candide

CANDIDE Voltaire 1759 © 1998, Electronic Scholarly Publishing Project http://www.esp.org This electronic edition is made freely available for scholarly or educational purposes, provided that this copyright notice is included. The manuscript may not be reprinted or redistributed for commercial purposes without permission. TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1.....................................................................................1 How Candide Was Brought Up in a Magnificent Castle and How He Was Driven Thence CHAPTER 2.....................................................................................3 What Befell Candide among the Bulgarians CHAPTER 3.....................................................................................6 How Candide Escaped from the Bulgarians and What Befell Him Afterward CHAPTER 4.....................................................................................8 How Candide Found His Old Master Pangloss Again and What CHAPTER 5...................................................................................11 A Tempest, a Shipwreck, an Earthquake, and What Else Befell Dr. Pangloss, Candide, and James, the Anabaptist CHAPTER 6...................................................................................14 How the Portuguese Made a Superb Auto-De-Fe to Prevent Any Future Earthquakes, and How Candide Underwent Public Flagellation CHAPTER 7...................................................................................16 How the Old Woman Took Care Of Candide, and How He Found the Object of -

Leonard Bernstein

chamber music with a modernist edge. His Piano Sonata (1938) reflected his Leonard Bernstein ties to Copland, with links also to the music of Hindemith and Stravinsky, and his Sonata for Clarinet and Piano (1942) was similarly grounded in a neoclassical aesthetic. The composer Paul Bowles praised the clarinet sonata as having a "tender, sharp, singing quality," as being "alive, tough, integrated." It was a prescient assessment, which ultimately applied to Bernstein’s music in all genres. Bernstein’s professional breakthrough came with exceptional force and visibility, establishing him as a stunning new talent. In 1943, at age twenty-five, he made his debut with the New York Philharmonic, replacing Bruno Walter at the last minute and inspiring a front-page story in the New York Times. In rapid succession, Bernstein Leonard Bernstein photo © Susech Batah, Berlin (DG) produced a major series of compositions, some drawing on his own Jewish heritage, as in his Symphony No. 1, "Jeremiah," which had its first Leonard Bernstein—celebrated as one of the most influential musicians of the performance with the composer conducting the Pittsburgh Symphony in 20th century—ushered in an era of major cultural and technological transition. January 1944. "Lamentation," its final movement, features a mezzo-soprano He led the way in advocating an open attitude about what constituted "good" delivering Hebrew texts from the Book of Lamentations. In April of that year, music, actively bridging the gap between classical music, Broadway musicals, Bernstein’s Fancy Free was unveiled by Ballet Theatre, with choreography by jazz, and rock, and he seized new media for its potential to reach diverse the young Jerome Robbins. -

Candide a Satirically Comedic Opera in Two Acts Music by Leonard Bernstein Libretto by Lillian Hellman

Eight Hundred Tenth Program of the 2011-12 Season _______________________ Indiana University Opera Theater presents as its 424th production Candide A Satirically Comedic Opera in Two Acts Music by Leonard Bernstein Libretto by Lillian Hellman Based on the novella of the same name by Voltaire Kevin Noe, Conductor Candace Evans, Stage Director and Choreographer C. David Higgins, Set and Costume Designer Todd Hensley, Lighting Designer Sylvia McNair, Diction Coach Susan Swaney, Chorus Master ____________________ Musical Arts Center Friday, April Sixth Saturday, April Seventh Friday, April Thirteenth Saturday, April Fourteenth Eight O’Clock music.indiana.edu Cast of Characters Candide . Will Perkins, Michael Porter Voltaire/Pangloss/Martin/Cacambo . .Joseph Mace, Sean McCarther Cunegonde. Katelyn Lee, Shannon Love Maximilian. Brayton Arvin, Joseph Legaspi The Old Lady . .Ashley Stone, Laura Thoreson Inquisitor 3/Don Issachar/Captain/Tsar Ivan. Allen Pruitt Paquette . Kellie Cullinan, Audrey Escots Grand Inquisitor/Governor/Vanderdendur/Ragotski. Corey Bonar, Andrew Morstein Act 1 Sailor/Inquisitor 2/Jesuit 1/Hermann Augustus . .Brian Darsie Bulgarian Officer 1/Senor 1/Aide (Buenos Aires)/Charles Edward . Ben Smith Bulgarian Officer 2/Informer 2/Senor 2 . Max Zander Baron/Informer 1/King of Eldorado/Stanislaus . .Matt Cooksey Inquisitor 1/Archbishop/Sultan Achmet/Crook . .Bradford Thompson Bearkeeper . .Tyler Henderson Cosmetic Merchant . David Margulis Junkman. Zachary Coates Alchemist . Andrew Lunsford Croupier . Lorenzo Garcia Doctor. Chris Seefeldt Judge 1. Alex Nelson Judge 2. Preston Orr Judge 3. Andrew Richardson Baroness . .Kelsea Webb King of Bulgaria . Deiran Manning Businessman bound for Lisbon. Brandon Shapiro Executioner . .Ryan Kieran Executioner’s Assistant . Taylor Henninger Sailor 2. Benjamin Cortez Penitent 1 . Behrouz Farrokhi Penitent 2 .