Chapter 2: Issues Arising from the Inquiry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Chronological History

A Chronological History December 2016 Pedro Heilbron, CEO of Copa Airlines, elected as new Chairman of the Star Alliance Chief Executive Board November 2016 Star Alliance Gold Track launched in Frankfurt, Star Alliance’s busiest hub October 2016 Juneyao Airlines announced as future Connecting Partner of Star Allianceseal partnership August 2016 Star Alliance adds themed itineraries to its Round the World product portfolio July 2016 Star Alliance Los Angeles lounge wins Skytrax Award for second year running Star Alliance takes ‘Best Alliance’ title at Skytrax World Airline Awards June 2016 New self-service check-in processes launched in Tokyo-Narita Star Alliance announces Jeffrey Goh will take over as Star Alliance CEO from 2017, on the retirement of Mark Schwab Swiss hosts Star Alliance Chief Executive Board meeting in Zurich. The CEOs arrive on the first passenger flight of the Bombardier C Series. Page 1 of 1 Page 2 of 2 April 2016 Star Alliance: Global travel solutions for conventions and meetings at IMEX March 2016 Star Alliance invites lounge guests to share tips via #irecommend February 2016 Star Alliance airlines launch new check-in processes at Los Angeles’ Tom Bradley International Terminal (TBIT) Star Alliance Gold Card holders enjoy free upgrades on Heathrow Express trains Star Alliance supports Ramsar’s Youth Photo Contest – Alliance’s Biosphere Connections initiative now in its ninth year January 2016 Gold Track priority at security added as a Star Alliance Gold Status benefit December 2015 Star Alliance launches Connecting -

Alliance Receives Regulatory Approval to Commence Revenue Operations with Embraer E190 Jets

Alliance Aviation Services Limited ACN 153 361 525 | ABN 96 153 361 525 1st April 2021 PO Box 1126, Eagle Farm QLD 4009 T +61 7 3212 1212 | F +61 7 3212 1522 www.allianceairlines.com.au ASX RELEASE Alliance Aviation Services Limited (“Alliance”) (ASX: AQZ) Alliance Receives Regulatory Approval to Commence Revenue Operations with Embraer E190 jets Fleet Update Regulatory Update Alliance is pleased to announce that yesterday it received regulatory approval from the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) to commence commercial operations with its Embraer E190 aircraft and a revised Air Operators Certificate has been issued. This follows an intense six-month programme of aircraft and spare parts acquisition, maintenance, training and regulatory and compliance checks. Alliance CEO, Lee Schofield commented, “We would like to thank CASA, our staff involved in the programme and our project contractors for delivering these approvals within the timeframe allocated.” First commercial services are scheduled for 10th April and the previously announced wet lease services to be provided to Qantas will commence as scheduled on 25th May 2021 with three aircraft. Operating bases for these aircraft will be Adelaide and Darwin. Fokker Fleet Update The total fleet of 43 Fokker aircraft are in revenue service and being operated across FIFO, charter and wet lease operations. Embraer Fleet Update Alliance has firm purchase commitments for the delivery of 30 Embraer E190 aircraft. Page 2 As of today,18 aircraft have been paid for and delivered to Alliance with the status as follows: Delivered to Australia – 5 In Base Maintenance overseas – 3 In storage pending base maintenance – 10 The balance of the 12 aircraft will be delivered progressively through until November 2021. -

World Air Transport Statistics, Media Kit Edition 2021

Since 1949 + WATSWorld Air Transport Statistics 2021 NOTICE DISCLAIMER. The information contained in this publication is subject to constant review in the light of changing government requirements and regulations. No subscriber or other reader should act on the basis of any such information without referring to applicable laws and regulations and/ or without taking appropriate professional advice. Although every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, the International Air Transport Associ- ation shall not be held responsible for any loss or damage caused by errors, omissions, misprints or misinterpretation of the contents hereof. Fur- thermore, the International Air Transport Asso- ciation expressly disclaims any and all liability to any person or entity, whether a purchaser of this publication or not, in respect of anything done or omitted, and the consequences of anything done or omitted, by any such person or entity in reliance on the contents of this publication. Opinions expressed in advertisements ap- pearing in this publication are the advertiser’s opinions and do not necessarily reflect those of IATA. The mention of specific companies or products in advertisement does not im- ply that they are endorsed or recommended by IATA in preference to others of a similar na- ture which are not mentioned or advertised. © International Air Transport Association. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, recast, reformatted or trans- mitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval sys- tem, without the prior written permission from: Deputy Director General International Air Transport Association 33, Route de l’Aéroport 1215 Geneva 15 Airport Switzerland World Air Transport Statistics, Plus Edition 2021 ISBN 978-92-9264-350-8 © 2021 International Air Transport Association. -

Airline Competition in Australia Report 3: March 2021

Airline competition in Australia Report 3: March 2021 accc.gov.au Australian Competition and Consumer Commission 23 Marcus Clarke Street, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, 2601 © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 This work is copyright. In addition to any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all material contained within this work is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence, with the exception of: the Commonwealth Coat of Arms the ACCC and AER logos any illustration, diagram, photograph or graphic over which the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission does not hold copyright, but which may be part of or contained within this publication. The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on the Creative Commons website, as is the full legal code for the CC BY 3.0 AU licence. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Director, Content and Digital Services, ACCC, GPO Box 3131, Canberra ACT 2601. Important notice The information in this publication is for general guidance only. It does not constitute legal or other professional advice, and should not be relied on as a statement of the law in any jurisdiction. Because it is intended only as a general guide, it may contain generalisations. You should obtain professional advice if you have any specific concern. The ACCC has made every reasonable effort to provide current and accurate information, but it does not make any guarantees regarding the accuracy, currency or completeness of that information. Parties who wish to re-publish or otherwise use the information in this publication must check this information for currency and accuracy prior to publication. -

Alliance Acquires an Additional Two E190 Aircraft

Alliance Aviation Services Limited 28th June 2021 ACN 153 361 525 | ABN 96 153 361 525 PO Box 1126, Eagle Farm QLD 4009 T +61 7 3212 1212 | F +61 7 3212 1522 ASX RELEASE www.allianceairlines.com.au Alliance Aviation Services Limited (“Alliance”) (ASX: AQZ) Alliance acquires an additional two E190 aircraft Alliance today announces that it has entered into a binding agreement to purchase two additional E190 aircraft which will take the total committed fleet to 32. These aircraft have previously been operated by Helvetic Airways in Switzerland and both aircraft have recently undertaken full base maintenance checks. As a result of the maintenance status of these aircraft, their entry into service will be fast- tracked which will allow Alliance to accelerate its E190 operational expansion. The aircraft are currently located in Basel and will be flown to Norwich, UK this week where they will be painted in Alliance livery and subsequently ferried to Australia. Purchase consideration is consistent with previous E190 fleet purchases. Alliance currently has seven E190s in Australia with the remaining 25 to enter revenue service during the next 12 months. Alliance will release it FY21 financial results on the 11th August 2021. - Ends - This announcement has been authorised for release by the Managing Director of Alliance Aviation Services Limited. Page 2 About the Alliance Group Alliance is Australasia’s leading provider of contract, charter and allied aviation and maintenance services currently employing in excess of 750 full time staff. The Company provides essential services to mining, energy, tourism, and government sectors and holds IATA’s IOSA certification and Flight Safety Foundation “BARS Gold” status, the first such carrier in Australia to be so recognised. -

Airlines Codes

Airlines codes Sorted by Airlines Sorted by Code Airline Code Airline Code Aces VX Deutsche Bahn AG 2A Action Airlines XQ Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Acvilla Air WZ Denim Air 2D ADA Air ZY Ireland Airways 2E Adria Airways JP Frontier Flying Service 2F Aea International Pte 7X Debonair Airways 2G AER Lingus Limited EI European Airlines 2H Aero Asia International E4 Air Burkina 2J Aero California JR Kitty Hawk Airlines Inc 2K Aero Continente N6 Karlog Air 2L Aero Costa Rica Acori ML Moldavian Airlines 2M Aero Lineas Sosa P4 Haiti Aviation 2N Aero Lloyd Flugreisen YP Air Philippines Corp 2P Aero Service 5R Millenium Air Corp 2Q Aero Services Executive W4 Island Express 2S Aero Zambia Z9 Canada Three Thousand 2T Aerocaribe QA Western Pacific Air 2U Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Amtrak 2V Aeroejecutivo SA de CV SX Pacific Midland Airlines 2W Aeroflot Russian SU Helenair Corporation Ltd 2Y Aeroleasing SA FP Changan Airlines 2Z Aeroline Gmbh 7E Mafira Air 3A Aerolineas Argentinas AR Avior 3B Aerolineas Dominicanas YU Corporate Express Airline 3C Aerolineas Internacional N2 Palair Macedonian Air 3D Aerolineas Paraguayas A8 Northwestern Air Lease 3E Aerolineas Santo Domingo EX Air Inuit Ltd 3H Aeromar Airlines VW Air Alliance 3J Aeromexico AM Tatonduk Flying Service 3K Aeromexpress QO Gulfstream International 3M Aeronautica de Cancun RE Air Urga 3N Aeroperlas WL Georgian Airlines 3P Aeroperu PL China Yunnan Airlines 3Q Aeropostal Alas VH Avia Air Nv 3R Aerorepublica P5 Shuswap Air 3S Aerosanta Airlines UJ Turan Air Airline Company 3T Aeroservicios -

Die Folgende Liste Zeigt Alle Fluggesellschaften, Die Über Den Flugvergleich Von Verivox Buchbar Sein Können

Die folgende Liste zeigt alle Fluggesellschaften, die über den Flugvergleich von Verivox buchbar sein können. Aufgrund von laufenden Updates einzelner Tarife, technischen Problemen oder eingeschränkten Verfügbarkeiten kann es vorkommen, dass einzelne Airlines oder Tarife nicht berechnet oder angezeigt werden können. 1 Adria Airways 2 Aegean Airlines 3 Aer Arann 4 Aer Lingus 5 Aeroflot 6 Aerolan 7 Aerolíneas Argentinas 8 Aeroméxico 9 Air Algérie 10 Air Astana 11 Air Austral 12 Air Baltic 13 Air Berlin 14 Air Botswana 15 Air Canada 16 Air Caraibes 17 Air China 18 Air Corsica 19 Air Dolomiti 20 Air Europa 21 Air France 22 Air Guinee Express 23 Air India 24 Air Jamaica 25 Air Madagascar 26 Air Malta 27 Air Mauritius 28 Air Moldova 29 Air Namibia 30 Air New Zealand 31 Air One 32 Air Serbia 33 Air Transat 34 Air Asia 35 Alaska Airlines 36 Alitalia 37 All Nippon Airways 38 American Airlines 39 Arkefly 40 Arkia Israel Airlines 41 Asiana Airlines 42 Atlasglobal 43 Austrian Airlines 44 Avianca 45 B&H Airlines 46 Bahamasair 47 Bangkok Airways 48 Belair Airlines 49 Belavia Belarusian Airlines 50 Binter Canarias 51 Blue1 52 British Airways 53 British Midland International 54 Brussels Airlines 55 Bulgaria Air 56 Caribbean Airlines 57 Carpatair 58 Cathay Pacific 59 China Airlines 60 China Eastern 61 China Southern Airlines 62 Cimber Sterling 63 Condor 64 Continental Airlines 65 Corsair International 66 Croatia Airlines 67 Cubana de Aviacion 68 Cyprus Airways 69 Czech Airlines 70 Darwin Airline 71 Delta Airlines 72 Dragonair 73 EasyJet 74 EgyptAir 75 -

Family Friendly Airline List

Family Friendly airline list Over 50 airlines officially approve the BedBox™! Below is a list of family friendly airlines, where you may use the BedBox™ sleeping function. The BedBox™ has been thoroughly assessed and approved by many major airlines. Airlines such as Singapore Airlines and Cathay Pacific are also selling the BedBox™. Many airlines do not have a specific policy towards personal comforts devices like the BedBox™, but still allow its use. Therefore, we continuously aim to keep this list up to date, based on user feedback, our knowledge, and our communication with the relevant airline. Aeromexico Japan Airlines - JAL Air Arabia Maroc Jet Airways Air Asia Jet Time Air Asia X Air Austral JetBlue Air Baltic Kenya Airways Air Belgium KLM Air Calin Kuwait Airways Air Caraibes La Compagnie Air China LATAM Air Europa LEVEL Air India Lion Airlines Air India Express LOT Polish Airlines Air Italy Luxair Air Malta Malaysia Airlines Air Mauritius Malindo Air Serbia Middle East Airlines Air Tahiti Nui Nok Air Air Transat Nordwind Airlines Air Vanuatu Norwegian Alaska Airlines Oman Air Alitalia OpenSkies Allegiant Pakistan International Airlines Alliance Airlines Peach Aviation American Airlines LOT Polish Airlines ANA - Air Japan Porter AtlasGlobal Regional Express Avianca Royal Air Maroc Azerbaijan Hava Yollary Royal Brunei AZUL Brazilian Airlines Royal Jordanian Bangkok Airways Ryanair Blue Air S7 Airlines Bmi regional SAS Brussels Airlines Saudia Cathay Dragon Scoot Cathay Pacific Silk Air CEBU Pacific Air Singapore Airlines China Airlines -

Plane E-List by Airfleets Oceania

Plane e-List by Airfleets Oceania Issue 30 http://www.airfleets.net Notice This document contains the list of all aircraft currently active in the region supported by this listing. Note that the following aircraft types are listed in this document. - Airbus A300 - Airbus A310 - Airbus A318 - Airbus A319 - Airbus A320 - Airbus A321 - Airbus A330 - Airbus A340 - Airbus A380 - ATR 42/72 - BAe 146 / Avro RJ - Boeing 717 - Boeing 737 - Boeing 737 Next Gen - Boeing 747 - Boeing 757 - Boeing 767 - Boeing 777 - Boeing 787 - Canadair Regional Jet - Concorde - Dash 8 - Embraer 120 Brasilia - Embraer 135/145 - Embraer 170/175 - Embraer 190/195 - Fokker 50 - Fokker 70/100 - Lockheed L-1011 TriStar - McDonnell Douglas DC-10 - McDonnell Douglas MD-11 - McDonnell Douglas MD-80/90 - Saab 2000 - Saab 340 - Sukhoi SuperJet 100 The author reserves the right not to be responsible for the topicality, correctness, completeness or quality of the information provided. Liability claims regarding damage caused by the use of any information provided, including any kind of information which is incomplete or incorrect,will therefore be rejected. No part of this letter or information contained in it may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means. Abbreviations used MSN : Manufactured Serial Number Reg : Registration Man. Year : Manufactured Year Ex : Last 5 previous registrations For more information about aircraft listed in this document, go to http://www.airfleets.net Contents Australia . 4 Airnorth Regional . 4 Alliance Airlines . 4 Australian Air Express . 4 Cobham Aviation . 4 Eastern Australia . 5 Jetcraft Aviation . 5 Jetstar . 5 LADS . 6 National Jet-Surveillance . -

Qantas Frequent Flyer Benefits Guidebook

BENEFITS GUIDEBOOK Making the most of your membership≥ GF3001Mar10 1 Contents≥ 2 Membership overview 7 Earning points 8 In the air 21 On the ground 47 Using points 49 Award flights and upgrades 67 Qantas Frequent Flyer Store 73 Your account 81 Where your points could take you 91 Terms and conditions 128 Contact details 129 Index This easy guide to your membership explains it all, step by step. Read on to find out how you can get the most from your membership and keep the guide handy so you’re familiar with the Terms and Conditions of the program. The index at the back of this guide will help you to find the information you need easily. The information is current as at the date of publication (March 2010). You’ll always find the latest information at qantas.com/frequentflyer 2 3 Don’t forget to give us your email address Then you will be amongst the first to know about our member specials, including Award Flight opportunities Welcome aboard! and special offers from our program partners. You have a lot to look forward to as a Qantas Make the most of your membership. Simply make Frequent Flyer sure we have your email address and register your There are so many ways you can enjoy our program. email preferences – just go to ‘Your Profile’ under You can earn Qantas Frequent Flyer points every time you ‘Your Account’ at qantas.com/frequentflyer fly on eligible flights* with Qantas, Jetstar, oneworld® to register your email preferences. You can also Alliance Airlines and our partner airlines. -

53 - Attachment A

53 - Attachment A Airservices Australia – Multi-Use Panel Arrangements Service Discipline Firm BECA Peckvonhartel Group ARUP Design Services AMC Projects GHD Sinclair Knight Merz Change Management SMS Consulting Nova Systems Consulting Construction Site Supervision Aecom Asset Technology Pacific AECOM GHD BECA Norman Disney Young Zamatech SEMF Engineering Sinclair Knight Merz GHD Sinclair Knight Merz Aecom Energetics Lovell Chen Environmental and Heritage Services SEMF AECOM BECA GHD Sinclair Knight Merz SMS Management Technology Information and Communications Technology Asset Technology Pacific AECOM Radio Electrical and Lines Assistance NEC Australia Kinetic Defence Services AMOG Safety Engineering Management NOVA GHD Sinclair Knight Merz BECA Rider Levett & Bucknall SEMF Survey Services WT Partnership Testing and Inspection GHD Codarra PPI Uni SA VoTech Systems Engineering Training Services (SETS) EC&S Airbiz Aviation Aircraft Noise Modelling & Assessment To70 Aviation IT Security Saltbush Oakton Accounting and Assurance Services PricewaterhouseCoopers Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Financial Services KPMG NERA Economic Consulting Ernst & Young Competition Economics Group (CEG) Ernst & Young PricewaterhouseCoopers Tax KPMG 53 - Attachment B Current CASA Panels and 101 Web Technology Pty Ltd MULs Aircraft and Simulator Multi- Action Aviation Pty Ltd Use-List Aircraft and Simulator Multi- Ad Astral Aviation Use-List Current CASA Panels and Adecco Australia Pty Ltd (Icon) MULs Aerial Agriculture Pty Ltd T/AS Fleet Aircraft and Simulator Multi- -

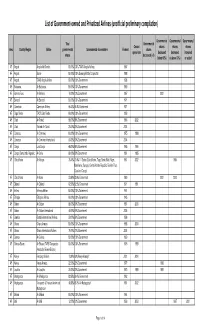

List of Government-Owned and Privatized Airlines (Unofficial Preliminary Compilation)

List of Government-owned and Privatized Airlines (unofficial preliminary compilation) Governmental Governmental Governmental Total Governmental Ceased shares shares shares Area Country/Region Airline governmental Governmental shareholders Formed shares operations decreased decreased increased shares decreased (=0) (below 50%) (=/above 50%) or added AF Angola Angola Air Charter 100.00% 100% TAAG Angola Airlines 1987 AF Angola Sonair 100.00% 100% Sonangol State Corporation 1998 AF Angola TAAG Angola Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1938 AF Botswana Air Botswana 100.00% 100% Government 1969 AF Burkina Faso Air Burkina 10.00% 10% Government 1967 2001 AF Burundi Air Burundi 100.00% 100% Government 1971 AF Cameroon Cameroon Airlines 96.43% 96.4% Government 1971 AF Cape Verde TACV Cabo Verde 100.00% 100% Government 1958 AF Chad Air Tchad 98.00% 98% Government 1966 2002 AF Chad Toumai Air Tchad 25.00% 25% Government 2004 AF Comoros Air Comores 100.00% 100% Government 1975 1998 AF Comoros Air Comores International 60.00% 60% Government 2004 AF Congo Lina Congo 66.00% 66% Government 1965 1999 AF Congo, Democratic Republic Air Zaire 80.00% 80% Government 1961 1995 AF Cofôte d'Ivoire Air Afrique 70.40% 70.4% 11 States (Cote d'Ivoire, Togo, Benin, Mali, Niger, 1961 2002 1994 Mauritania, Senegal, Central African Republic, Burkino Faso, Chad and Congo) AF Côte d'Ivoire Air Ivoire 23.60% 23.6% Government 1960 2001 2000 AF Djibouti Air Djibouti 62.50% 62.5% Government 1971 1991 AF Eritrea Eritrean Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1991 AF Ethiopia Ethiopian