The Ilyderabad Political System and Its Participants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pt. Bansi Dhar Nehru Was Born in 1843 at Delhi

The firm foundation of the Mughal empire in India was laid by a Uzbek Mongol warrior Zahiruddin Mohammand Babar, who was born in 1483 in a tiny village Andijan on the border of Uzbekistan and Krigistan after defeating the Sultan of Delhi Ibrahim Lodi in the battle of Panipat which took place in 1526, The Rajputs soon thereafter under the command of Rana Sanga challenged the authority of Babar, but were badly routed in the battle of Khanwa near Agra on 16th March, 1527. Babar with a big army then went upto Bihar to crush the revolt of Afgan chieftains and on the way his commander in chief Mir Baqi destroyed the ancient Ram Temple at Ayodhya and built a mosque at that spot in 1528. Babar than returned back to Agra where he died on 26th December 1530 dur t o injuries received in the battle with Afgans in 1529 at the Ghaghra’s is basin in Bihar. After Babar’s death his son Nasiruddin Humanyu ascended the throne, but he had to fight relentless battels with various rebellious chieftains for fight long years. The disgruntled Afghan chieftains found Sher Shah Suri as an able commander who defeated Humanyu in the battle of Chausa in Bihar and assumed power at Delhi in 1543. Sher Shah Suri died on 22nd May 1545 due to injuries suffered in a blast after which the Afghan power disintegrated. Hymanyu then taking full advantage of this fluid political situation again came back to India with reinforcements from Iran and reoccupied the throne at Delhi after defeating Adil Shah in the second battle of Panipat in 1555. -

Central Administration of Akbar

Central Administration of Akbar The mughal rule is distinguished by the establishment of a stable government and other social and cultural activities. The arts of life flourished. It was an age of profound change, seemingly not very apparent on the surface but it definitely shaped and molded the socio economic life of our country. Since Akbar was anxious to evolve a national culture and a national outlook, he encouraged and initiated policies in religious, political and cultural spheres which were calculated to broaden the outlook of his contemporaries and infuse in them the consciousness of belonging to one culture. Akbar prided himself unjustly upon being the author of most of his measures by saying that he was grateful to God that he had found no capable minister, otherwise people would have given the minister the credit for the emperor’s measures, yet there is ample evidence to show that Akbar benefited greatly from the council of able administrators.1 He conceded that a monarch should not himself undertake duties that may be performed by his subjects, he did not do to this for reasons of administrative efficiency, but because “the errors of others it is his part to remedy, but his own lapses, who may correct ?2 The Mughal’s were able to create the such position and functions of the emperor in the popular mind, an image which stands out clearly not only in historical and either literature of the period but also in folklore which exists even today in form of popular stories narrated in the villages of the areas that constituted the Mughal’s vast dominions when his power had not declined .The emperor was looked upon as the father of people whose function it was to protect the weak and average the persecuted. -

Mughals at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, 1500 - 1605

Mughals at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, 1500 - 1605 A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Andrew de la Garza Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin, Advisor; Stephen Dale; Jennifer Siegel Copyright by Andrew de la Garza 2010 Abstract This doctoral dissertation, Mughals at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, examines the transformation of warfare in South Asia during the foundation and consolidation of the Mughal Empire. It emphasizes the practical specifics of how the Imperial army waged war and prepared for war—technology, tactics, operations, training and logistics. These are topics poorly covered in the existing Mughal historiography, which primarily addresses military affairs through their background and context— cultural, political and economic. I argue that events in India during this period in many ways paralleled the early stages of the ongoing “Military Revolution” in early modern Europe. The Mughals effectively combined the martial implements and practices of Europe, Central Asia and India into a model that was well suited for the unique demands and challenges of their setting. ii Dedication This document is dedicated to John Nira. iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Professor John F. Guilmartin and the other members of my committee, Professors Stephen Dale and Jennifer Siegel, for their invaluable advice and assistance. I am also grateful to the many other colleagues, both faculty and graduate students, who helped me in so many ways during this long, challenging process. -

Mughal Empire CHAPTER

16 Mughal Empire CHAPTER A new age begins with the unification of India under the Mughals. The Mughals created an empire between 1550 and 1700 AD and expanded their empire from around Delhi to almost the entire subcontinent. Their administrative arrangements, ideas of governance and architecture continued to influence rulers long after the decline of their empire. Today the Prime Minister of India addresses the Coin showing nation on Independence Day from the ramparts of the Red Jahangir Fort in Delhi, the residence of the Mughal emperors. Who were the Mughals? leave his ancestral throne due to the The Mughals were from ruling families invasion of another ruler. After years of of Central Asian countries like Uzbekistan wandering he seized Kabul in 1504 AD. In and Mongolia. Babur, the first Mughal 1526 AD he defeated the Sultan of Delhi, emperor (1526 - 1530 AD), was forced to Ibrahim Lodi and captured Delhi and Agra. Fig 16.1 Red Fort. Important Mughal emperors - Major campaigns and events Babur 1526-1530 AD 1526 AD – defeated Ibrahim Lodi and established control over Agra and Delhi. He introduced cannons and guns in Indian warfare. Humayun 1530-1556 AD Sher Khan defeated Humayun forcing him to flee to Iran. In Iran Humayun received help from the Safavid Shah. He recaptured Delhi in 1555 AD but died in an accident the following year. Akbar 1556-1605 AD Akbar was 13 years old when he became emperor. He rapidly conquered Bengal, Central India, Rajasthan and Gujarat.Thereafter he also conquered Afghanistan, Kashmir and portions of the Deccan. Look at his empire in Map 1. -

Humayun Badshah

HUMAYUN ON THE THRONE HUMAYUN BADSHAH BY S. K. BANERJI, M.A., PH.D. (LOND.) READER IN INDIAN HISTORY, LUCKNOW UNIVERSITY WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY SIR E. DENISON ROSS FORMERLY DIRECTOR, SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL STUDIES, LONDON HUMPHREY MILFORD OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 1938 OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS AMEN HOUSE, LONDON, B.C. 4 EDINBURGH GLASGOW NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE CAPETOWN BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS HUMPHREY MILFORD PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY PRINTED IN INDIA AT THE MODERN ART PRESS, CALCUTTA INTRODUCTION It was with great pleasure that I accepted Dr S. K. Banerji's invitation to write a few words by way of intro1 duction to his Life of the Emperor Humayun, seeing that it was under my supervision, at the School of Oriental Studies, London, that he prepared his PH.D. thesis on the early years of Humayun 's reign. During the two years that he spent here I had ample opportunity of seeing his work and formed a high opinion of his capacity and enthusiasm. Since his return to India he has become Reader in Indian History at the Lucknow University, and he has devoted such leisure as his duties permitted him to the expansion of his thesis and a continuation of the life of Humayun, with a view to producing a full and definite history of that gifted but unfortunate monarch. The present volume brings the story down to the defeat of Humayun at the hands of Sher Shah in 1540 and his consequent abandonment of his Empire : the rest of the story will be told in a second volume which is under preparation. -

History of Aurangzib Based on Original Sources

|I||UH| HISTORY OF AURANGZIB Vol. 11. Works by Jadunath Sarkar, M.A. 1. History of Aurangzib, based on Persian sources. Rs. Vol. 1. Reign of Shah Jahan, pp. 402. Vol.11. War of Succession, pp.328. 3J each. 2. Anecdotes of Aurangzib (English translation and notes) and Historical Essays, pp. 248. 1-3 text with an 3. Ahkam-i-Alamgiri, Persian English translation {Anecdotes of Aiirang- 5i6) and notes, pp. 72 + 146 ... ... i 4. Chaitanya's Pilgrimages and Teachings, being an English translation of his contem- porary biography, Chaitanya-charita- mrita, Madhya-lila, pp. 320+ ... 2 5. India of Aurangzib : Statistics, Topography and Roads, with translations from the Khulasat-ui-tawarikh and the Chahar Gulshan. (Not a history), pp. 300 ... 2^ 6. Economics of British India, 3rd ed., pp. 300 + (In preparation) .. •3 and Ravindra- 7. Essays, Social Literary, by nath Tagore, translated into English. (In preparation). SOLD BY M. C. Sarkar it Sons, 75, Harrison Road, Calcutta. S. K. Lahiri & Co., 56, College Str., Calcutta. Madras. G. A. Natesan, 3, Shunkurama Chetti Str., D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., 103, Medows Str., Bombay. LuzAC & Co., 46, Great Russell Str., LONDON. HISTORY OF AURANGZIB Mainly based on Persian Sources. JADUNATH SARKAR, M.A., Professor, Patna College. Vol. II. War of Succession. M. C. SARKAR & 0. SONS, ^^c ^ ' ]\^' Harrison <" 75, Road, \^ \ ^ ' \ CALCUTTA. * -v ^ >^* 1912. 55. net. Rs. 3-8 As. bs .7 KUNTALINE PRESS. Printed by Purna Chandra Dass, 6i & 62, BovvBAZAR Street, Calcutta. PUBLISHKD BY M. C. SaRKAR & SoNS, 75, Harrison Road, Calcutta. CONTENTS. Chapter XV. Battle of Dharmat. —tries to avert a Jaswant at Uijain, i —his movements, 2 — in his —his battle, 3—his difficulties, 5 treachery ranks, 7 — of 1 1 order battle, plan of battle, 9—contending forces, Van, J2— Rajput Van charges, 14—defence by Aurangzib's left IS— Rajputs destroved, iS—Murad attacks the Imperial — 21— 22— wing, 19 Jaswant's flight, plunder, —Aurangzib's in 23—his memorial buildings, 24 casualties, gain prestige, — Samn- 25—Aurangzib crosses the Chambal, 28 reaches garh, 30. -

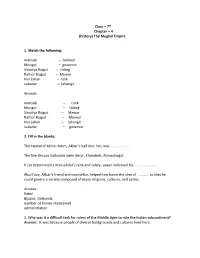

Class – 7Th Chapter – 4 (History) the Mughal Empire 1. Match the Following

Class – 7th Chapter – 4 (history) The Mughal Empire 1. Match the following: mansab – Marwar Mongol – governor Sisodiya Rajput – Uzbeg Rathor Rajput – Mewar Nur Jahan – rank subadar – Jahangir Answer: mansab – rank Mongol – Uzbeg Sisodiya Rajput – Mewar Rathor Rajput – Marwar Nur Jahan – Jahangir subadar – governor 2. Fill in the blanks: The capital of Mirza Hakim, Akbar’s half-bro: her, was ………………… The five Deccan Sultanate were Berar, Khandesh, Ahmadnagar, If zat determined a mansabdar’s rank and salary, sewer indicated his……………………… Abul Faze, Akbar’s friend and counsellor, helped him frame the idea of …………. so that he could govern a society composed of many religions, cultures, and castes. Answer: Kabul Bijapur, Golconda number of horses maintained administration 1. Why was it a difficult task for rulers of the Middle Ages to rule the Indian subcontinent? Answer: It was because people of diverse backgrounds and cultures lived here. 2. Who was Genghis Khan? Answer: He was the ruler of the Mongol tribes, China and Central Asia. 3. Who was Babur? Answer: He was the first Mughal emperor and reigned from 1526 to 1530 4. Name the battlefield where Ibrahim Lodi was defeated by Babur? Answer: Panipat. 5. To whom did Babur defeat at Chanderi?[V- Imp.] Answer: Babur defeated the Rajputs at Chanderi 6. What forced Hwnayun to flee to Iran? Answer: After being defeated by Sher Khan at Chausa in 1539 and Kanauj in 1540 Humayun fled to Iran. 7. At what age did Akbar become the emperor of the Mughal Empire? Answer: Akbar became the emperor of the Mughal Empire at the age of 13. -

The Mughal Empire

Chapter 5 8 THE MUGHAL EMPIRE ike the Ottomans, the Mughals carried the dilemma of post-Abbasid L politics outside the Arid Zone and resolved it. Unlike the Ottomans, the Mughals did not expand the frontiers of Muslim political power, ex- cept on some fringes. They established a new polity ruled by an estab- lished dynasty in territory that Muslims already ruled. The dynastic setting and the environment—physical, social, and cultural—requires careful explanation in order to make the Mughal success comprehensible. This section describes the multiple contexts in which the Mughal Empire developed and then summarizes the most important characteristics of the Mughal polity. Historians have traditionally identified Babur as the founder of the Mughal Empire and considered his invasion of northern India in 1526 as the beginning of Mughal history. Both the identification and date are mis- leading. Babur’s grandson, Akbar, established the patterns and institutions that defined the Mughal Empire; the prehistory of the empire dates back to Babur’s great-great-grandfather Timur’s invasion of north India in 1398. Because Timur remained in Hindustan (literally, “the land of Hin- dus”; the Persian word for northern India) only a short time and his troops sacked Delhi thoroughly, historians have traditionally treated his incur- sion as a raid rather than an attempt at conquest. Timur, however, did not attempt to establish direct Timurid rule in most of the areas he conquered; 201 202 5 – THE MUGHAL EMPIRE he generally left established dynasties in place or established surrogates of his own. His policy in Hindustan was the same; he apparently left one Khizr Khan as his governor in Delhi. -

Composition and Role of the Nobility (1739-1761)

COMPOSITION AND ROLE OF THE NOBILITY (1739-1761) ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Boctor of ^l)iIo^op}|p IN HISTORY BY MD. SHAKIL AKHTAR Under the Supervision of DR. S. LIYAQAT H. MOINI (Reader) CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2008 ABSTRACT Foregoing study ' composition and role of the Nobility (1739- 1761)', explore the importance of Nobility in Political, administrative, Sicio-cultural and economic spheres. Nobility , 'Arkan-i-Daullat' (Pillars of Empire) generally indicates'the'class of people, who were holding hi^h position and were the officers of the king as well as of the state. This ruling elite constituting of various ethnic group based on class, political sphere. In Indian sub-continent they served the empire/state most loyally and obediently specially under the Great Mughals. They not only helped in the expansion of the Empire by leading campaign and crushing revolt for the consolidation of the empire, but also made remarkable and laudable contribution in the smooth running of the state machinery and played key role in the development of social life and composite culture. Mughal Emperor Akbar had organized the nobility based on mgnsabdari system and kept a watchful eye over the various groups, by introducing local forces. He had tried to keep a check and balance over the activities, which was carried by his able successors till the death of Aurangzeb. During the period of Later Mughals over ambitious, self centered and greedy nobles, kept their interest above state and the king and had started to monopolies power and privileges under their own authority either at the court or in the far off provinces. -

Mughal Administration

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA GIFT OF HORACE W. CARPENTIER Mughal Administration 'PATNA UNIVERSITY READERSHIP LECTURES, 1920.) SARKAR, M.A., JADUNATH m Indian Educational Service, Bihar. 1920. M. C. SARKAR & SONS, Calcutta. Rs.2. PUBLISHED BY S. C. Sarkar of M C. SARKAR & SONS BY THE SAME AUTHOR. 1. History of Aurangzib, 4 vols. ... Rs. 3-8 each. Vol. I. Reign of Shah Jahan. II. War of Succession, 1657—58. „ III. Northern India, 1658—1681. „ IV. Southern India, 1644—1689. 2. Shivaji and His Times, 2nd ed. ... Rs. 4. (Based on original Persian and Marathi sources and English and Dutch Factory Records). 3. Studies in Mughal India ... Rs. 2. (Twenty-two historical essays.) 4. Anecdotes of Aurangzib, (Ahkarn- i-Alamgiri) Persian text, English trans, and notes ... ... Re. 1-8 5. Chaitanya's life and teachings, 2nd ed., greatly enlarged ... Rs. 3. (From his original Bengali biography.) 6. Economics of British India, 4ch ed., i-evise<], enlarged and brought up to date ... ... Rs. 3. M. C. SARKAR & SONS, 90/2, Harrison Road, Calcutta. Printer : S. C. MaJUMDAR, SRI GOURANGA PRESS, 7///, Mirzapur Street, Calcutta. CONTENTS. Chapter I . —The Government : its character and Aims ... ... ... I —25 Previous studies of Mughal administration, 2—subjects of these six lectures, 3—Mughal administrative system influenced Hindu and British governments, 4—aims of Mughal State, 6— foreign elements in Mughal administration, 8—military nature of the government, 10—State factories, 13—excess of records, 15—law and justice, 16—Muslim law in India, 20—no socialistic activity, 23—people left alone, 24. Chapter II. -

18 Baumer.Pdf

ASIAN STUDIES AT HAWAII, NO. 12 Aspects of B~ngali . History and Society Rachel Van M. Baumer Editor ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAM UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF HAWAII UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII LIBRARY Copyright © 1975 by The University Press of Hawaii All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: Aspects of Bengali history and society. (Asian studies at Hawaii; no. 12) "Essays delivered by most of the guest speakers in a seminar on Bengal convened in the spring of 1972 at the University of Hawaii." Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Bengal-Civilization-Addresses, essays, lectures. 2. Bengal-History-Addresses, essays, lectures. I. Baumer, Rachel Van M., 1928- ed. II. Series. DS3.A2A82 no. 12 [DS485.B44] 915.4'14'03 73-90491 ISBN 0-8248-0318-3 Dedicated to the memory of our colleagues whose lives and fruitful scholar ship were cut off during the independence struggle in Bangladesh. \)j<j 4\31 <j ~\3 ~TbT ~9j$ff<j;ft I - ~D"5' L Contents Introduction vii Hinduism and Islam in Medieval Bengal Edward C. Dimock, Jr. Norms of Family Life and Personal Morality among the Bengali Hindu Elite, 1600-1850 Tapan Raychaudhuri 13 Economic Foundations of the Bengal Renaissance Blair B. Kling 26 The Universal Man and the Yellow Dog: The Orientalist Legacy and the Problem of Brahmo Identity in the Bengal Renaissance David Kopf 43 The Reinterpretation of Dharma in Nineteenth-Century Bengal: Righteous Conduct for Man in the Modern World Rachel Van M. -

The Mughal Empire

4 THE MUGHAL EMPIRE uling as large a territory as the Indian subcontinent R with such a diversity of people and cultures was an extremely difficult task for any ruler to accomplish in the Middle Ages. Quite in contrast to their predecessors, the Mughals created an empire and accomplished what had hitherto seemed possible for only short periods of time. From the latter half of the sixteenth century they expanded their kingdom from Agra and Delhi, until in the seventeenth century they controlled nearly all of the subcontinent. They imposed structures of administration and ideas of governance that outlasted their rule, leaving a political legacy that succeeding rulers of the subcontinent could not ignore. Today the Prime Minister of India addresses the nation on Independence Day from the ramparts of the Red Fort in Delhi, the residence of the Mughal emperors. Fig. 1 The Red Fort. 45 THE MUGHAL EMPIRE 2021-22 Who were the Mughals? The Mughals were descendants of two great lineages of rulers. From their mother’s side they were descendants of Genghis Khan (died 1227), the Mongol ruler who ruled over parts of China and Central Asia. From their father’s side they were the successors of Timur (died 1404), the ruler of Iran, Iraq and modern-day Turkey. However, the Mughals did not like to be called Mughal or Mongol. This was because Genghis Khan’s memory was associated with the massacre of innumerable people. It was also linked with the Uzbegs, their Mongol competitors. On the other hand, the Mughals were ? Fig. 2 A miniature painting (dated 1702-1712) of Timur, his descendants Do you think this and the Mughal emperors.