Humayun Badshah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stenographer (Post Code-01)

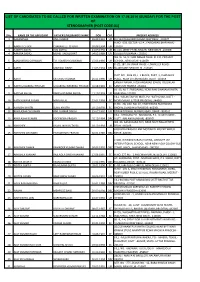

LIST OF CANDIDATES TO BE CALLED FOR WRITTEN EXAMINATION ON 17.08.2014 (SUNDAY) FOR THE POST OF STENOGRAPHER (POST CODE-01) SNo. NAME OF THE APPLICANT FATHER'S/HUSBAND'S NAME DOB CAT. PRESENT ADDRESS 1 AAKANKSHA ANIL KUMAR 28.09.1991 UR B II 544 RAGHUBIR NAGAR NEW DELHI -110027 H.NO. -539, SECTOR -15-A , FARIDABAD (HARYANA) - 2 AAKRITI CHUGH CHARANJEET CHUGH 30.08.1994 UR 121007 3 AAKRITI GOYAL AJAI GOYAL 21.09.1992 UR B -116, WEST PATEL NAGAR, NEW DELHI -110008 4 AAMIRA SADIQ MOHD. SADIQ BHAT 04.05.1989 UR GOOSU PULWAMA - 192301 WZ /G -56, UTTAM NAGAR NEAR, M.C.D. PRIMARY 5 AANOUKSHA GOSWAMI T.R. SOMESH GOSWAMI 15.03.1995 UR SCHOOL, NEW DELHI -110059 R -ZE, 187, JAI VIHAR PHASE -I, NANGLOI ROAD, 6 AARTI MAHIPAL SINGH 21.03.1994 OBC NAJAFGARH NEW DELHI -110043 PLOT NO. -28 & 29, J -1 BLOCK, PART -1, CHANAKYA 7 AARTI SATENDER KUMAR 20.01.1990 UR PLACE, NEAR UTTAM NAGAR, DELHI -110059 SANJAY NAGAR, HOSHANGABAD (GWOL TOLI) NEAR 8 AARTI GULABRAO THOSAR GULABRAO BAKERAO THOSAR 30.08.1991 SC SANTOSHI TEMPLE -461001 I B -35, N.I.T. FARIDABAD, NEAR RAM DHARAM KANTA, 9 AASTHA AHUJA RAKESH KUMAR AHUJA 11.10.1993 UR HARYANA -121001 VILL. -MILAK TAJPUR MAFI, PO. -KATHGHAR, DISTT. - 10 AATIK KUMAR SAGAR MADAN LAL 22.01.1993 SC MORADABAD (UTTAR PRADESH) -244001 H.NO. -78, GALI NO. 02, KHATIKPURA BUDHWARA 11 AAYUSHI KHATRI SUNIL KHATRI 10.10.1993 SC BHOPAL (MADHYA PRADESH) -462001 12 ABHILASHA CHOUHAN ANIL KUMAR SINGH 25.07.1992 UR RIYASAT PAWAI, AURANGABAD, BIHAR - 824101 VILL. -

The Pashtun Counter-Narrative

Middle East Critique ISSN: 1943-6149 (Print) 1943-6157 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ccri20 The Pashtun Counter-Narrative Shah Mahmoud Hanifi To cite this article: Shah Mahmoud Hanifi (2016): The Pashtun Counter-Narrative, Middle East Critique, DOI: 10.1080/19436149.2016.1208354 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19436149.2016.1208354 Published online: 18 Jul 2016. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ccri20 Download by: [James Madison University] Date: 18 July 2016, At: 07:36 Middle East Critique, 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19436149.2016.1208354 The Pashtun Counter-Narrative SHAH MAHMOUD HANIFI James Madison University, Harrisonburg, VA, USA ABSTRACT THIS article provides a critical appraisal of ethnicity as the primary route to knowing Afghanistan. The critique is founded on the fundamental voiceless-ness of Pashtuns in academic and international discussions about them. It utilizes longue durée history to amplify the salience of migration as an alternate framework for understanding Afghanistan, and it analyzes the place of the Pashto language in the modern Afghan state structure. The article also discusses the impact of the nineteenth-century British Indian colonial authority Mountstuart Elphinstone and the twentieth-century American specialist Louis Dupree to illustrate the persistence of Orientalism in Anglo-American imperial knowledge about Afghanistan. KEY WORDS: Afghanistan; Louis Dupree; Mountstuart Elphinstone; ethnicity; migration; orientalism; Pashto; Pashtuns The aim of this article is to prompt readers to question commonly held assumptions and representations of Afghanistan. -

Iran and Israel's National Security in the Aftermath of 2003 Regime Change in Iraq

Durham E-Theses IRAN AND ISRAEL'S NATIONAL SECURITY IN THE AFTERMATH OF 2003 REGIME CHANGE IN IRAQ ALOTHAIMIN, IBRAHIM,ABDULRAHMAN,I How to cite: ALOTHAIMIN, IBRAHIM,ABDULRAHMAN,I (2012) IRAN AND ISRAEL'S NATIONAL SECURITY IN THE AFTERMATH OF 2003 REGIME CHANGE IN IRAQ , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4445/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 . IRAN AND ISRAEL’S NATIONAL SECURITY IN THE AFTERMATH OF 2003 REGIME CHANGE IN IRAQ BY: IBRAHIM A. ALOTHAIMIN A thesis submitted to Durham University in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy DURHAM UNIVERSITY GOVERNMENT AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS March 2012 1 2 Abstract Following the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, Iran has continued to pose a serious security threat to Israel. -

Pt. Bansi Dhar Nehru Was Born in 1843 at Delhi

The firm foundation of the Mughal empire in India was laid by a Uzbek Mongol warrior Zahiruddin Mohammand Babar, who was born in 1483 in a tiny village Andijan on the border of Uzbekistan and Krigistan after defeating the Sultan of Delhi Ibrahim Lodi in the battle of Panipat which took place in 1526, The Rajputs soon thereafter under the command of Rana Sanga challenged the authority of Babar, but were badly routed in the battle of Khanwa near Agra on 16th March, 1527. Babar with a big army then went upto Bihar to crush the revolt of Afgan chieftains and on the way his commander in chief Mir Baqi destroyed the ancient Ram Temple at Ayodhya and built a mosque at that spot in 1528. Babar than returned back to Agra where he died on 26th December 1530 dur t o injuries received in the battle with Afgans in 1529 at the Ghaghra’s is basin in Bihar. After Babar’s death his son Nasiruddin Humanyu ascended the throne, but he had to fight relentless battels with various rebellious chieftains for fight long years. The disgruntled Afghan chieftains found Sher Shah Suri as an able commander who defeated Humanyu in the battle of Chausa in Bihar and assumed power at Delhi in 1543. Sher Shah Suri died on 22nd May 1545 due to injuries suffered in a blast after which the Afghan power disintegrated. Hymanyu then taking full advantage of this fluid political situation again came back to India with reinforcements from Iran and reoccupied the throne at Delhi after defeating Adil Shah in the second battle of Panipat in 1555. -

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

Chronicles of Rajputana: the Valour, Sacrifices and Uprightness of Rajputs

Quest Journals Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science Volume 9 ~ Issue 8 (2021)pp: 15-39 ISSN(Online):2321-9467 www.questjournals.org Research Paper Chronicles of Rajputana: the Valour, Sacrifices and uprightness of Rajputs Suman Lakhani ABSTRACT Many famous kings and emperors have ruled over Rajasthan. Rajasthan has seen the grandeur of the Rajputs, the gallantry of the Mughals, and the extravagance of Jat monarchs. None the less history of Rajasthan has been shaped and molded to fit one typical school of thought but it holds deep secrets and amazing stories of splendors of the past wrapped in various shades of mysteries stories. This paper is an attempt to try and unearth the mysteries of the land of princes. KEYWORDS: Rajput, Sesodias,Rajputana, Clans, Rana, Arabs, Akbar, Maratha Received 18 July, 2021; Revised: 01 August, 2021; Accepted 03 August, 2021 © The author(s) 2021. Published with open access at www.questjournals.org Chronicles of Rajputana: The Valour, Sacrifices and uprightness of Rajputs We are at a fork in the road in India that we have traveled for the past 150 years; and if we are to make true divination of the goal, whether on the right hand or the left, where our searching arrows are winged, nothing could be more useful to us than a close study of the character and history of those who have held supreme power over the country before us, - the waifs.(Sarkar: 1960) Only the Rajputs are discussed in this paper, which is based on Miss Gabrielle Festing's "From the Land of the Princes" and Colonel James Tod's "Annals of Rajasthan." Miss Festing's book does for Rajasthan's impassioned national traditions and dynastic records what Charles Kingsley and the Rev. -

Late Onset of Sufism in Azerbaijan and the Influence of Zarathustra Thoughts on Its Fundamentals

International Journal of Philosophy and Theology September 2014, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 93-106 ISSN: 2333-5750 (Print), 2333-5769 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2014. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijpt.v2n3a7 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.15640/ijpt.v2n3a7 Late Onset of Sufism in Azerbaijan and the Influence of Zarathustra Thoughts on its Fundamentals Parisa Ghorbannejad1 Abstract Islamic Sufism started in Azerbaijan later than other Islamic regions for some reasons.Early Sufis in this region had been inspired by mysterious beliefs of Zarathustra which played an important role in future path of Sufism in Iran the consequences of which can be seen in illumination theory. This research deals with the reason of the delay in the advent of Sufism in Azerbaijan compared with other regions in a descriptive analytic method. Studies show that the deficiency of conqueror Arabs, loyalty of ethnic people to Iranian religion and the influence of theosophical beliefs such as heart's eye, meeting the right, relation between body and soul and cross evidences in heart had important effects on ideas and thoughts of Azerbaijan's first Sufis such as Ebn-e-Yazdanyar. Investigating Arab victories and conducting case studies on early Sufis' thoughts and ideas, the author attains considerable results via this research. Keywords: Sufism, Azerbaijan, Zarathustra, Ebn-e-Yazdanyar, Islam Introduction Azerbaijan territory2 with its unique geography and history, was the cultural center of Iran for many years in Sasanian era and was very important for Zarathustra religion and Magi class. 1 PhD, Faculty of Science, Islamic Azad University, Urmia Branch,WestAzarbayjan, Iran. -

Origin and Development of Urdu Language in the Sub- Continent: Contribution of Early Sufia and Mushaikh

South Asian Studies A Research Journal of South Asian Studies Vol. 27, No. 1, January-June 2012, pp.141-169 Origin and Development of Urdu Language in the Sub- Continent: Contribution of Early Sufia and Mushaikh Muhammad Sohail University of the Punjab, Lahore ABSTRACT The arrival of the Muslims in the sub-continent of Indo-Pakistan was a remarkable incident of the History of sub-continent. It influenced almost all departments of the social life of the people. The Muslims had a marvelous contribution in their culture and civilization including architecture, painting and calligraphy, book-illustration, music and even dancing. The Hindus had no interest in history and biography and Muslims had always taken interest in life-history, biographical literature and political-history. Therefore they had an excellent contribution in this field also. However their most significant contribution is the bestowal of Urdu language. Although the Muslims came to the sub-continent in three capacities, as traders or business men, as commanders and soldiers or conquerors and as Sufis and masha’ikhs who performed the responsibilities of preaching, but the role of the Sufis and mash‘iskhs in the evolving and development of Urdu is the most significant. The objective of this paper is to briefly review their role in this connection. KEY WORDS: Urdu language, Sufia and Mashaikh, India, Culture and civilization, genres of literature Introduction The Muslim entered in India as conquerors with the conquests of Muhammad Bin Qasim in 94 AH / 712 AD. Their arrival caused revolutionary changes in culture, civilization and mode of life of India. -

STANDARD5 SESSION-2020-21 SUBJECT-ENGLISH(Coursebook)

SARDAR PATEL PUBLIC SCHOOL,KAMLAPUR ( BOKARO) STANDARD 5 SESSION-2020-21 SUBJECT- ENGLISH (Coursebook) Prepared By-Vijay Shankar 12.. The Story Of Panna Dai (Page no-92 to 93) A. Write True or False. 1.True 2.False 3.False 4.True 5.False 6.True 7.True B.Answer these questions. Answers 1.Rana Sanga was a Rajput ruler of Mewar.He died after losing the Battle of Khanwa against the Mughal emperor Babur. 2.Vikramaditya Singh's rule didn't last long because once he abused and misbehaved with an old chieftain in the court.After that, many nobles and other chieftains placed him under palace arrest and made Udai Singh the heir-elect to the throne. 3. Panna Dai was a loyal and trusted wet nurse to Udai. In the royal household, she was hired to take care of Rani Karnavati's younger son Udai.She treated him just like her son Chandan. 4.In order to fulfil his ambition,Banvir killed Rana Vikramaditya in his palace 5.Punna sacrificed her own son’s life to save the little prince Udai Singh. She was able to send Udai Singh out safely. Punna put her son in place of Udai Singh, when Banbir came to kill the prince. Banbir killed her son. Thus Punna sacrificed her son to save the prince. 6.Once a group of chiefs and noblemen went to Kumbhalgarh to interview Udai Singh and Panna Dai.They were quite impressed with his mannerism and personality.It was then clearly established that he was indeed Udai Singh. -

One Odd Day PDF Book

ONE ODD DAY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Doris Fisher,Dani Sneed,Karen Lee | 32 pages | 10 Sep 2007 | Arbordale Publishing | 9781934359334 | English | United States One Odd Day PDF Book Extinction Extinction event Holocene extinction Human extinction List of extinction events Genetic erosion Genetic pollution. At the death of 20th Imam Amir, one branch of the Mustaali faith claimed that he had transferred the Imamate to his son At-Tayyib Abu'l-Qasim, who was then two years old. One need not wait for any other Mahdi now. Li Hong. End times Apocalypticism. A hadith from [Ali] adds in this regard, "Mahdi will not appear unless one-third of the people are killed; another one-third die, and the remaining one-third survive. Guess which number of the following sequence is the odd one out. His name will be my name, and his father's name my father's name [9]. Get our free widgets. Since Sunnism has no established doctrine of Mahdi, compositions of Mahdi varies among Sunni scholars. November Learn how and when to remove this template message. But if you see something that doesn't look right, click here to contact us! Word of the Day vindicate. Home Maintenance. The term Mahdi does not occur in the Quran. Within a few years, the collection—including works by Vasily Kandinsky, Paul Klee and Marc Chagall —had outgrown the small space. Follow us. Gog and Magog Messianic Age. This article relies too much on references to primary sources. It is argued that one was to be born and rise within the dispensation of Muhammad, who by virtue of his similarity and affinity with Jesus, and the similarity in nature, temperament and disposition of the people of Jesus' time and the people of the time of the promised one the Mahdi is called by the same name. -

Chapter Preview

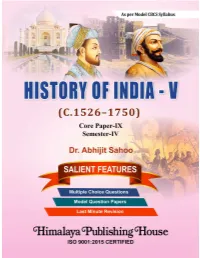

As per Model CBCS Syllabus HISTORY OF INDIA-V [C.1526-1750] Core Paper IX Semester-IV Dr. Abhijit Sahoo Lecturer in History Shishu Ananta Mahavidyalaya, Balipatna, Khordha, Odisha ISO 9001:2015 CERTIFIED © Author No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording and/or otherwise without the prior written permission of the author and the publisher. First Edition : 2021 Published by : Mrs. Meena Pandey for Himalaya Publishing House Pvt. Ltd., “Ramdoot”, Dr. Bhalerao Marg, Girgaon, Mumbai - 400 004. Phone: 022-23860170, 23863863; Fax: 022-23877178 E-mail: [email protected]; Website: www.himpub.com Branch Offices : New Delhi : “Pooja Apartments”, 4-B, Murari Lal Street, Ansari Road, Darya Ganj, New Delhi - 110 002. Phone: 011-23270392, 23278631; Fax: 011-23256286 Nagpur : Kundanlal Chandak Industrial Estate, Ghat Road, Nagpur - 440 018. Phone: 0712-2721215, 3296733; Telefax: 0712-2721216 Bengaluru : Plot No. 91-33, 2nd Main Road, Seshadripuram, Behind Nataraja Theatre, Bengaluru - 560 020. Phone: 080-41138821; Mobile: 09379847017, 09379847005 Hyderabad : No. 3-4-184, Lingampally, Besides Raghavendra Swamy Matham, Kachiguda, Hyderabad - 500 027. Phone: 040-27560041, 27550139 Chennai : New No. 48/2, Old No. 28/2, Ground Floor, Sarangapani Street, T. Nagar, Chennai - 600 017. Mobile: 09380460419 Pune : “Laksha” Apartment, First Floor, No. 527, Mehunpura, Shaniwarpeth (Near Prabhat Theatre), Pune - 411 030. Phone: 020-24496323, 24496333; Mobile: 09370579333 Lucknow : House No. 731, Shekhupura Colony, Near B.D. Convent School, Aliganj, Lucknow - 226 022. Phone: 0522-4012353; Mobile: 09307501549 Ahmedabad : 114, “SHAIL”, 1st Floor, Opp. -

QBRI Leads Neurological Research Initiatives

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Bengaluru FC take on Air Force Club of INDEX DOW JONES QE NYMEX QATAR 2, 16 COMMENT 14, 15 North Sea oil fl ood REGION 3 BUSINESS 1 – 12 Iraq in AFC Cup looms as Opec 17,911.27 9,955.99 44.12 ARAB WORLD 3 CLASSIFIED 7, 8 -19.40 -117.07 -0.54 INTERNATIONAL 4 – 13 SPORTS 1 – 8 plans output cuts fi nal today -0.11% -1.16% -1.21% Latest Figures published in QATAR since 1978 SATURDAY Vol. XXXVII No. 10263 November 5, 2016 Safar 5, 1438 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Festival showcases Chinese culture In brief QBRI leads neurological QATAR | Phone call Congratulations to al-Hariri HE the Prime Minister and Minister of Interior Sheikh Abdullah bin Nasser research bin Khalifa al-Thani yesterday held a telephone conversation with Saad al-Hariri, congratulating the latter for becoming the prime minister of Lebanon. HE Sheikh Abdullah bin Nasser stressed during the initiatives call that the State of Qatar would continue its support to Lebanon and QBRI is pioneering an remain committed to the latter’s epidemiological study to find the security and stability. He wished the Zhejiang’s leading performers entertaining the crowd with traditional music and dances yesterday at the Chinese Festival 2016, prevalence rate of autism in Qatar Lebanese people further progress which concludes today at the Museum of Islamic Art Park. The four-day event, which features a variety of Chinese cultural and prosperity. Lebanon’s newly- shows and activities, art and crafts exhibitions, food, and workshops, is a key part of the Qatar China Year of Culture, which By Joseph Varghese elected President Michel Aoun on ends in December.