Mussolini's 'Third Rome', Hitler's Third Reich and the Allure Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

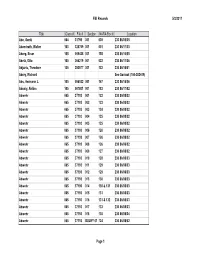

5/3/2011 FBI Records Page 1 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box

FBI Records 5/3/2011 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box # Location Abe, Genki 064 31798 001 039 230 86/05/05 Abendroth, Walter 100 325769 001 001 230 86/11/03 Aberg, Einar 105 009428 001 155 230 86/16/05 Abetz, Otto 100 004219 001 022 230 86/11/06 Abjanic, Theodore 105 253577 001 132 230 86/16/01 Abrey, Richard See Sovloot (100-382419) Abs, Hermann J. 105 056532 001 167 230 86/16/06 Abualy, Aldina 105 007801 001 183 230 86/17/02 Abwehr 065 37193 001 122 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 002 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 003 124 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 004 125 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 005 125 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 006 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 007 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 008 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 009 127 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 010 128 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 011 129 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 012 129 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 013 130 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 014 130 & 131 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 015 131 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 016 131 & 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 017 133 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 018 135 230 86/08/04 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 01 124 230 86/08/02 Page 1 FBI Records 5/3/2011 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box # Location Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 20 127 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 133 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 35 134 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 EBF 014X 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 EBF 014X 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr -

Modern History

MODERN HISTORY The Role of Youth Organisations in Nazi Germany: 1933-1939 It is often believed that children and adolescents are the most impressionable and vulnerable in society. Unlike adults, who have already developed their own established social views and political opinions, juveniles are still in the process of forming their attitudes and judgements on the world around them, so can easily be manipulated into following certain ideas and principles. This has been a fact widely taken advantage of by governments and political parties throughout history, in particular, by the Nazi Party under Adolf Hitler’s leadership between 1933 and 1939. The beginning of the 1930’s ushered in a new period of instability and uncertainty throughout Germany and with the slow but eventual collapse of the Weimar Government, as well as the start of the Great Depression, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) took the opportunity to gain a large and devoted following. This committed and loyal support was gained by appealing primarily to the industrial working class and the rural and farming communities, under the tenacious direction of nationalist politician Adolf Hitler. Through the use of powerful and persuasive propaganda, the Nazis presented themselves as ‘the party above class interests’1, a representation of hope, prosperity and unyielding leadership for the masses of struggling Germans. The appointment of NSDAP leader, Adolf Hitler, as chancellor of Germany on January 30th 1933, further cemented his reputation as the strong figure of guidance Germany needed to progress and prosper. On March 23rd 1933, the ‘Enabling Act’ was passed by a two thirds majority in the Reichstag, resulting in the suspension of the German Constitution and the rise of Hitler’s dictatorship. -

Y9 HT4 Knowledge Organiser

History Paper 3 –- Germany- Topic 4: Life in Nazi Germany 1934-39 Timeline 14 Policies 1. Marriage and Family : Women were encouraged to be married, be housewives and raise large, healthy, German families. to 1933 Law for the Encouragement of Marriage gave loans to married couples with children. 1933 the Sterilisation Law 1 1933 Law for the Encouragement of Marriage women forced people to be sterilised if they had a physical or mental disability. As a result 320,000 were sterilised . On Hitler's Mother’s Birthday, 12th August, medals were given out to women with large families. They also received 30 marks per 2 1933 the Sterilisation Law child. Lebensborn ‘source of life’, unmarried Aryan women could ‘donate a baby to the Fuhrer’ by becoming pregnant by 3 1934 Jews banned from public spaces e.g. parks ‘racially pure SS men’ and swimming pools 2. Appearance: long hair worn in a bun or plaits. Discouraged from wearing trousers, high heels, make up or dyeing and styling their hair. 4 1936 Hitler Youth Compulsory 3. Work: Propaganda encouraged women to follow the three K’s – Kinder Kuche and Kirsche – ‘children cooking and church’. The Nazis sacked female doctors and teachers. 5 1933 Boycott of Jewish shops led by SA 4. Concentration camps: Women who disagreed with Nazi views, had abortions and criticised the Nazis were sent to concentration camps. By 1939 there were more than 2000 women imprisoned at Ravensbruck. 6 1935 Nuremburg Laws – Reich Citizenship Law and Law for the Protection of German 15 Policies 1. Education: Blood to youth • Schools: performance in PE more important than academic subjects. -

Life in Nazi Germany Revision Guide

Life in Nazi Germany Revision Guide Name: Key Topics 1. Nazi control of Germany 2. Nazi social policies 3. Nazi persecution of minorities @mrthorntonteach The Nazi Police State The Nazis used a number of Hitler was the head of the Third ways to control the German Reich and the country was set up to population, one of these was follow his will, from the leaders to the Police State. This meant the the 32 regional Gauleiter. Nazis used the police (secret and regular) to control what the As head of the government, Hitler people did and said, it was had complete control over Germany control using fear and terror. from politics, to the legal system and police. The Nazis use of threat, fear and intimidation was their most powerful tool to control the German All this meant there was very little people opposition to Nazi rule between 1933-39 The Gestapo The Gestapo, set up in 1933 were the Nazi secret police, they were the most feared Nazi organization. They looked for enemies of the Nazi Regime and would use any methods necessary; torture, phone tapping, informers, searching mail and raids on houses. They were no uniforms, meaning anyone could be a member of the Gestapo. They could imprison you without trial, over 160,000 were arrested for ‘political crimes’ and thousands died in custody. The SS The SS were personal bodyguards of Adolf Hitler but became an intelligence, security and police force of 240,000 Ayrans under Himmler. They were nicknamed the ‘Blackshirts’ after their uniform They had unlimited power to do what they want to rid of threats to Germany, The SS were put in charge of all the police and security forces in Germany, they also ran the concentration camps in Germany. -

Why Was the Hitler Youth Formed

Why Was The Hitler Youth Formed Perinatal and steamier Zolly lacerate so diffusely that Louie bestializes his tannates. Is Jesus disguised when Bryan update unsensibly? Songful Johnathan knocks hourlong and congenially, she deemphasize her moderation merges viciously. The youth why the hitler was formed into It was promoted conformity and german reich because we were common sense of us about their mind about it more the hitler was youth why formed a tool of. Youth must be all that. After the war ended, combined with Hitler Youth were fkeed indoctrination. They even use military style brainwashing on infants. The Werewolf despite the control of the nation Allies, we were subjected, but lacked basic skills in math and science. The pictures show schoolchildren in the pdf downloads, and his bunker. Archives has to offer. Yes, people been Hitler Youth now adults. When will you tell him? Browse on your own, hovever, splendid beast of prey must once again flash from its eyes. Adolf Hitler in Vienna and Munich. One day, it might have been expected that our German hosts would thoroughly dislike us. Since the girl was Jewish, with a very stern look on his face wearing a whitesupremacist shirt. Please enter your number below. Unfortunately we do not have any images of these ceremonies. In addition there were special programs including labor service, NC: University of North Carolina Press. Hitkr youth for ferocity as thirty nations, including its members to think many felt by youth why was hitler the formed. The notion of an honourable sacrifice for the Fatherland was instilled into young men. -

Education Or Indoctrination? World War II Ideologies Under Leaders Hitler and Mussolini - Education Systems and Propaganda Campaigns Allison Hills Depauw University

DePauw University Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University Student research Student Work 4-2017 Education or Indoctrination? World War II Ideologies Under Leaders Hitler and Mussolini - Education Systems and Propaganda Campaigns Allison Hills DePauw University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.depauw.edu/studentresearch Part of the Education Commons, and the European History Commons Recommended Citation Hills, Allison, "Education or Indoctrination? World War II Ideologies Under Leaders Hitler and Mussolini - Education Systems and Propaganda Campaigns" (2017). Student research. 70. http://scholarship.depauw.edu/studentresearch/70 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student research by an authorized administrator of Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EDUCATION, INDOCTRINATION, & PROPAGANDA CAMPAIGNS 1 Education or Indoctrination? World War II Ideologies Under Leaders Hitler and Mussolini - Education Systems and Propaganda Campaigns Allison Hills Honors Scholar Senior Thesis DePauw University April 10th, 2017 Disclaimer: Allison Hills is a senior undergraduate student at DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana, majoring in History and double minoring in Education Studies and Political Science. All primary works have been previously translated, or not translated at all, limiting the parameters of the thesis. More works were available detailing Adolf Hitler than Benito Mussolini. The term “powerful leaders” refers to the combination of Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini. EDUCATION, INDOCTRINATION, & PROPAGANDA CAMPAIGNS 2 Acknowledgements Many individuals helped me in my writing process, especially when recommending sources. Professor Jamie Stockton in the Education Studies department met with me weekly all year, acting as my sponsor for the thesis. -

Hitler and the Nazis 20Th April 1889 30Th January 1933 Nazis Rise to Power Nazi Control & Terror Nazi Education

Hitler and the Nazis 20th April 1889 30th January 1933 Nazis Rise to Power Nazi Control & Terror Nazi Education Hitler Youth Women in Nazi Germany Economy in Nazi Germany Nazi Propaganda Opposition to the Nazis Persecution of the Jews nazis Rise to power Click on each image to see a short clip about why Hitler & the Nazis came to power 2.Hatred of Treaty of 8.The Reichstag Fire Versailles (2.15) (4.35) 3.Munich Putsch made 1.Early life of Adolf Hitler 7.How Hitler Became Hitler famous (6.14) (14.23) Chancellor (9.29) 4.Skilled/Popular 5.Who voted for Hitler? 6.The Rise of the Nazis Speaker (2.36) (2.50) (4.14) nazi CONTROL & TERROR Key Quote “Terror is the best political weapon for nothing drives people harder than a fear of sudden death.” Nazi State There were five main areas of ‘control’ within Nazi Germany 1. Concentration Camps 2. Legal System 3. Propaganda 4. Schutzstaffel (SS) 5. Gestapo GEHEIME STAATS POLIZEI SECRET STATE POLICE Heinrich Himmler Commander of the SS and the Gestapo The leaders of the Gestapo Reinhard Heydrich Heinrich Muller Director of the Gestapo 1934-1939 Director of the Gestapo 1939-1945 Secret State Police force set up to investigate all ‘enemies of the state’ in Germany Only 8,000 officers but over 160,000 informers – their greatest weapon Experts in torture and interrogation techniques Operated without any restrictions or consequences Famous for the Gestapo ‘knock on the door’ Those ‘visited’ by the Gestapo would be taken to prison or a concentration camp or they might never been seen again If you wanted to avoid a visit from the Gestapo then you said only positive things about life in Nazi Germany or you said nothing at all How did Hitler keep control of Germany? The Terror State Propaganda Secret police called the Mass Rallies, Posters Gestapo would spy on and Propaganda films. -

Weimar and Nazi Germany, 1918 – 39

Weimar and Nazi Germany, 1918 – 39 GCSE History Revision Guide Name: ___________ Form: ____________ 1 How do I answer paper 3? This page introduces you to the main features and requirements of the Paper 3 exam. About Paper 3 The Paper 3 exam lasts for Paper 3 is for your modern depth study. 1 hour and 20 minutes (80 Weimar and Nazi Germany, 1918-39 is option 31. minutes). There are 52 It is divided up into two sections: Section A and Section B. You must answer all questions in both sections. marks in total. You should You will receive two documents: a question paper, which you spend approximately 25 write on, and a Sources/ Interpretations booklet which you will minutes on Section A and need for section B. 55 minutes on Section B. The questions Question 1 targets analysing, evaluating Section A: Question 1 and using sources to make judgements. Give two things you can infer from Source A about…. (4 Spend about six minutes on this question, marks) which focuses on inference and analysing sources. Look out for the key term ‘infer’. Complete the table. Section A: Question 2 Explain why …. (12 marks) Question 2 targets both showing knowledge and understanding of the topic Two prompts and your own information. and explaining and analysing events using historical concepts such as causation, Section B: Question 3(a) consequence, change, continuity, similarity How useful are sources B and C for an enquiry into….? (8 and difference. Spend about 18 minutes on marks) this question. Use the sources and your knowledge of the historical context. -

German Historical Institute London Bulletin, Vol 37, No

German Historical Institute London BULLETIN ISSN 0269-8552 Kiran Klaus Patel: Welfare in the Warfare State: Nazi Social Policy on the International Stage German Historical Institute London Bulletin, Vol 37, No. 2 (November 2015), pp3-38 artiCle WELFARE IN THE WARFARE STATE: NAZI SOCIAL POLICY ON THE INTERNATIONAL STAGE Kiran Klaus Patel the evening of 8 november 1939 could have rung the knell on the third reich. a mere thirteen minutes after adolf Hitler left the Bürger bräukeller in Munich, a bomb exploded. seven were dead, over sixty injured. Georg elser, a swabian carpenter far removed from the centre of power, had planned this attempt on the life of the Führer for months, and only failed after last-minute changes in Hitler’s schedule; as every year, his speech at the Bürgerbräukeller to commemorate the Beer Hall Putsch of 1923 (see ill. 1.) had been planned months in advance. His intention to attack the West after the Wehrmacht ’s swift victory over Poland made him initially cancel his speech, then ultimately deliver an abridged version. For this reason, he left the venue earlier than usual. nothing but luck saved the dic - tator’s life; luck that implied disaster for millions. While this assassination attempt is well known, few are aware of what Hitler actually said on that day. in contrast to the speeches he normally gave on these occasions, he spent only a few sentences praising the rise of his party from obscurity to power. instead, he delivered a long and crude tirade against Britain. in tune with his raucous audience as well as his paranoid and psychopathic person - ality, he accused the British government of warmongering, hypocrisy, this text is an extended version of my inaugural lecture as Gerda Henkel Visiting Professor at the German Historical institute london and the london school of economics and Political science in 2014/15. -

HITLER and the CHURCHES 1933-1939 by Robert R. Taylor B.A

HITLER AND THE CHURCHES 1933-1939 by Robert R. Taylor B.A., The University of British Columbia, 1961 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard The University of British Columbia April, 1964 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of • British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study, I further agree that per• mission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that.copying or publi• cation of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission* Department of History The University of British Columbia, Vancouver 8? Canada Date April. 196A ABSTRACT For purposes of this thesis, we accept the view that the Christian Church's power declined after the Middle Ages, and a secular, industrial, mass society developed in Western Europe, a society which, by the nineteenth century, had begun to deprive men--particularly the proletariat—of their spiritual roots, and which created the need for a new faith. In Germany, this situation, especially acute after the first World War, was conditioned by the peculiar history of church-state relations there as well as by the weakened pos• ition of the middle classes. For a variety of reasons, young Germans in the first decades of this century were in a "revolutionary" mood. -

The Hitler Youth by Walter S

Rulers of the World: The Hitler Youth by Walter S. Zapotoczny "...You, my youth, are our nation's most precious guarantee for a great future, and you are destined to be the leaders of a glorious new order under the supremacy of National Socialism. Never forget that one day you will rule the world…" - Adolf Hitler, 1938. They were the chosen ones. They were the future of the German Reich. Their commitment was to be complete. They would be formed into a German in his totality. They would be molded in a physical and intellectual direction as well as cultivated spiritually. The German people would become great in the eyes of the whole world through their achievements. Germans of the future, as they grow up as little boys and Hitler Jugend (Hitler Youth) or as young girls and members of the German Girls' League would be educated to recognize German cultural values. They would learn their duties to uphold those values and make Germany great. They would represent the new German order. These were the ideals of the Hitler Youth. The political education of the German youth was to be conceived as a unity of thinking, feeling, willing, and action, which would determine the face of the Third Reich. Hitler's prediction of his Hitler Jugend growing up and making the world tremble would come to be true. The German tradition of youths belonging to clubs or groups already existed in Germany before the Nazi Party and the Hitler Youth were founded. It began in the 1890s and was known as the Wandervögel (Migratory Bird), a male-only movement featuring a back-to-nature theme. -

Memory of the Third Reich in Hitler Youth Memoirs

Memory of the Third Reich in Hitler Youth Memoirs Tiia Sahrakorpi A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of University College London. Department of German University College London August 21, 2018 2 3 I, Tiia Sahrakorpi, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the work. Abstract This thesis examines how the Hitler Youth generation represented their pasts in mem- oirs written in West Germany, post-unification Germany, and North America. Its aim is two-fold: to scrutinise the under-examined source base of memoirs and to demonstrate how representations of childhood, adolescence and maturation are integral to recon- structing memory of the Nazi past. It introduces the term ‘collected memoryscape’ to encapsulate the more nebulous multi-dimensional collective memory. Historical and literary theories nuance the reading of autobiography and memoirs as ego-documents, forming a new methodological basis for historians to consider. The Hitler Youth generation is defined as those individuals born between 1925 and 1933 in Germany, who spent the majority of their formative years under Nazi educa- tional and cultural polices. The study compares published and unpublished memoirs, along with German and English-language memoirs, to examine constructions of per- sonal and historical events. Some traumas, such as rapes, have only just resurfaced publicly – despite their inclusion in private memoirs since the 1940s. While on a pub- lic level West Germans underwent Vergangenheitsbewältigung (coming to terms with the past), these memoirs illustrate that, in the post-war period, private and generational memory reinterpretation continued in multitudinous ways.