Memory of the Third Reich in Hitler Youth Memoirs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Germany Key Words

Germany Key Words Anti–Semitism Hatred of the Jews. Article 48 Part of the Weimar Constitution, giving the President special powers to rule in a crisis. Used By Chancellors to rule when they had no majority in the Reichstag – and therefore an undemocratic precedent for Hitler. Aryan Someone who Belongs to the European type race. To the Nazis this meant especially non– Jewish and they looked for the ideal characteristics of fair hair, Blue eyes... Autobahn Motorway – showpieces of the Nazi joB creation schemes Bartering Buying goods with other goods rather than money. (As happened in the inflation crisis of 1923) Bavaria Large state in the South of Germany. Hitler & Nazis’ original Base. Capital – Munich Beerhall Putsch Failed attempt to seize power By Hitler in NovemBer 1923. Hitler jailed for five years – in fact released Dec 1924 Brown Shirts The name given to the S.A. Centre Party Party representing Roman Catholics – one of the Weimar coalition parties. Dissolves itself July 1933. Chancellor Like the Prime Minister – the man who is the chief figure in the government, Coalition A government made up of a number of parties working together, Because of the election system under Weimar, all its governments were coalitions. They are widely seen as weak governments. Conscription Compulsory military service – introduced by Hitler April1935 in his drive to build up Germany’s military strength (against the terms of the Versailles Treaty) Conservatives In those who want to ‘conserve’ or resist change. In Weimar Germany it means those whose support for the RepuBlic was either weak or non–existent as they wanted a return to Germany’s more ordered past. -

Lesson 12: Handout 4, Document 1 German Youth in the 1930S: Selected Excerpted Documents

Lesson 12: Handout 4, Document 1 German Youth in the 1930s: Selected excerpted documents Changes at School (Excerpted from “Changes at School,” pp. 175–76 in Facing History and Ourselves: Holocaust and Human Behavior ) Ellen Switzer, a student in Nazi Germany, recalls how her friend Ruth responded to Nazi antisemitic propaganda: Ruth was a totally dedicated Nazi. Some of us . often asked her how she could possibly have friends who were Jews or who had a Jewish background, when everything she read and distributed seemed to breathe hate against us and our ancestors. “Of course, they don’t mean you,” she would explain earnestly. “You are a good German. It’s those other Jews . who betrayed Germany that Hitler wants to remove from influence.” When Hitler actually came to power and the word went out that students of Jewish background were to be isolated, that “Aryan” Germans were no longer to associate with “non-Aryans” . Ruth actually came around and apologized to those of us to whom she was no longer able to talk. Not only did she no longer speak to the suddenly ostracized group of class - mates, she carefully noted down anybody who did, and reported them. 12 Purpose: To deepen understanding of how propaganda and conformity influence decision-making. • 186 Lesson 12: Handout 4, Document 2 German Youth in the 1930s: Selected excerpted documents Propaganda and Education (Excerpted from “Propaganda and Education,” pp. 242 –43 in Facing History and Ourselves: Holocaust and Human Behavior ) In Education for Death , American educator Gregor Ziemer described school - ing in Nazi Germany: A teacher is not spoken of as a teacher ( Lehrer ) but an Erzieher . -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

Adventskalender Und Am 24

Jahrgang 43 Freitag, den 4. Dezember 2020 Nummer 49 Die Evangelische Kirchengemeinde Fränkisch-Crumbach informiert: Kein Adventskonzert 2020 Es gibt aber einen virtuellen Adventskalender und am 24. Dezember eine real geöffnete Türe Informationen auf www.kirche-fraenkisch-crumbach.de Fränkisch-Crumbach - 2 - Nr. 49/20 Hilfetelefon Gewalt gegen Frauen ...................... 0800/116016 Anonyme Alkoholiker ....................................Tel.: 06151 19295 Jahnstraße 22 (kath. Gemeindehaus), Reinheim Gruppentreffen montags von 18.00 bis 19.30 Uhr Gemeindeverwaltung Fränkisch-Crumbach Krankenhäuser Rodensteiner Straße 8 Kreiskrankenhaus Erbach, 64407 Fränkisch-Crumbach A.-Schweizer-Str. 10-20 ........................................... 06062/79-0 Tel.: 06164 9303-0, Fax: 06164 9303-93 HOSPIZ-Initiative Odenwald e.V., E-Mail: [email protected] Kreiskrankenh. Erbach ........................................ 06062/798000 Homepage: www.fraenkisch-crumbach.de Caritas Zentrum Erbach, Allgemeine Lebensberatung, Öffnungszeiten: Hauptstr. 42, 64711 Erbach, Montag und Dienstag: 8.30 - 12.00 Uhr Telefon: .............................................................. 06062 95533-0, Mittwoch 9.30 - 12.00 Uhr Telefax: 06062 95533-22, Donnerstag: 8.30 - 12.00 Uhr Email: [email protected], Internet: www.caritas-darmstadt.de und 13.00 - 18.00 Uhr Apotheken Freitag: 8.30 - 12.00 Uhr Rodenstein-Apotheke, Fränkisch-Crumbach ..................... 1451 Gingko-Apotheke, Brensbach ................................... 06161/566 Polizei ................................................................................. -

Northern Gothic: Werner Haftmann's German

documenta studies #11 December 2020 NANNE BUURMAN Northern Gothic: Werner Haftmann’s German Lessons, or A Ghost (Hi)Story of Abstraction This essay by the documenta and exhibition scholar Nanne Buurman I See documenta: Curating the History of the Present, ed. by Nanne Buurman and Dorothee Richter, special traces the discursive tropes of nationalist art history in narratives on issue, OnCurating, no. 13 (June 2017). German pre- and postwar modernism. In Buurman’s “Ghost (Hi)Story of Abstraction” we encounter specters from the past who swept their connections to Nazism under the rug after 1945, but could not get rid of them. She shows how they haunt art history, theory, the German feuilleton, and even the critical German postwar literature. The editor of documenta studies, which we founded together with Carina Herring and Ina Wudtke in 2018, follows these ghosts from the history of German art and probes historical continuities across the decades flanking World War II, which she brings to the fore even where they still remain implicit. Buurman, who also coedited the volume documenta: Curating the History of the Present (2017),I thus uses her own contribution to documenta studies to call attention to the ongoing relevance of these historical issues for our contemporary practices. Let’s consider the Nazi exhibition of so-called Degenerate Art, presented in various German cities between 1937 and 1941, which is often regarded as documenta’s negative foil. To briefly recall the facts: The exhibition brought together more than 650 works by important artists of its time, with the sole aim of stigmatizing them and placing them in the context of the Nazis’ antisemitic racial ideology. -

Paper Number: 2860 Claims on the Past: Cave Excavations by the SS Research and Teaching Community “Ahnenerbe” (1935–1945) Mattes, J.1

Paper Number: 2860 Claims on the Past: Cave Excavations by the SS Research and Teaching Community “Ahnenerbe” (1935–1945) Mattes, J.1 1 Department of History, University of Vienna, Universitätsring 1, 1010 Wien, Austria, [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Founded in 1935 by a group of fascistic scholars and politicians around Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, the “Ahnenerbe” proposed to research the cultural history of the Aryan race and to legitimate the SS ideology and Himmler’s personal interest in occultism scientifically. Originally organized as a private society affiliated to Himmler’s staff, the “Ahnenerbe” became one of the most powerful institutions in the Third Reich engaged with questions of archaeology, cultural heritage and politics. Its staff were SS members, consisting of scientific amateurs, occultists as well as established scholars who obtained the rank of an officer. Competing against the “Amt Rosenberg”, an official agency for cu ltural policy and surveillance in Nazi Germany, the research community “Ahnenerbe” had already become interested in caves and karst as excellent sites for fossil man investigations before 1937/38, when Himmler founded his own Department of Karst- and Cave Research within the “Ahnenerbe”. Extensive excavations in several German caves near Lonetal (G. Riek, R. Wetzel, O. Völzing), Mauern (R.R. Schmidt, A. Bohmer), Scharzfeld (K. Schwirtz) and Leutzdorf (J.R. Erl) were followed by research travels to caves in France, Spain, Ukraine and Iceland. After the establishment of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia in 1939, the “Ahnenerbe” even planned the appropriation of all Moravian caves to prohibit the excavations of local prehistorians and archaeologists from the “Amt Rosenberg”, who had to switch for their excavations to Figure 1: Prehistorian and SS- caves in Thessaly (Greece). -

Indictment Presented to the International Military Tribunal (Nuremberg, 18 October 1945)

Indictment presented to the International Military Tribunal (Nuremberg, 18 October 1945) Caption: On 18 October 1945, the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg accuses 24 German political, military and economic leaders of conspiracy, crimes against peace, war crimes and crimes against humanity. Source: Indictment presented to the International Military Tribunal sitting at Berlin on 18th October 1945. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, November 1945. 50 p. (Cmd. 6696). p. 2-50. Copyright: Crown copyright is reproduced with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office and the Queen's Printer for Scotland URL: http://www.cvce.eu/obj/indictment_presented_to_the_international_military_tribunal_nuremberg_18_october_1945-en- 6b56300d-27a5-4550-8b07-f71e303ba2b1.html Last updated: 03/07/2015 1 / 46 03/07/2015 Indictment presented to the International Military Tribunal (Nuremberg, 18 October 1945) INTERNATIONAL MILITARY TRIBUNAL THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, THE FRENCH REPUBLIC, THE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND, AND THE UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLICS — AGAINST — HERMANN WILHELM GÖRING, RUDOLF HESS, JOACHIM VON RIBBENTROP, ROBERT LEY, WILHELM KEITEL, ERNST KALTEN BRUNNER, ALFRED ROSENBERG, HANS FRANK, WILHELM FRICK, JULIUS STREICHER, WALTER FUNK, HJALMAR SCHACHT, GUSTAV KRUPP VON BOHLEN UND HALBACH, KARL DÖNITZ, ERICH RAEDER, BALDUR VON SCHIRACH, FRITZ SAUCKEL, ALFRED JODL, MARTIN BORMANN, FRANZ VON PAPEN, ARTUR SEYSS INQUART, ALBERT SPEER, CONSTANTIN VON NEURATH, AND HANS FRITZSCHE, -

Drucksache 19/417 19

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 19/417 19. Wahlperiode 12.01.2018 Antwort der Bundesregierung auf die Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Brigitte Freihold, Nicole Gohlke, Dr. Petra Sitte, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion DIE LINKE. – Drucksache 19/211 – Bildung und wissenschaftliche Forschung zum Holocaust und dem deutschen Vernichtungskrieg in Osteuropa durch das Zentrum für Militärgeschichte und Sozialwissenschaften der Bundeswehr in Potsdam Vorbemerkung der Fragesteller Das Zentrum für Militärgeschichte und Sozialwissenschaften der Bundeswehr in Potsdam (ZMSBw) vereinigt die geistes- und sozialwissenschaftliche For- schung der Bundeswehr. Interdisziplinär wird dort zu zentralen Problemstellun- gen der heutigen Streitkräfte geforscht, die sich aus Gegenwart und Geschichte ergeben. Die daraus entstehenden Veröffentlichungen richten sich einerseits an ein Fachpublikum und werden andererseits im Rahmen eines breiten Veröffent- lichungs- und Publikationsprogramms an deutsche Soldaten und Offiziere ver- mittelt. Eine kritische Aufarbeitung der NS-Geschichte, des Holocaust und des deutschen Vernichtungskrieges in Osteuropa und der Rolle der Wehrmacht, na- mentlich auch deren Nachwirkungen und Kontinuitäten in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, ist nach Auffassung der Fragesteller auch vor dem Hintergrund der Debatte um Leitbilder und Traditionen der Bundeswehr von enormer Be- deutung. Berichte über rechtsextreme Vorfälle oder die Festnahme eines Ober- leutnants der Bundeswehr aus Offenbach, der im Verdacht stand, einen Terror- anschlag geplant -

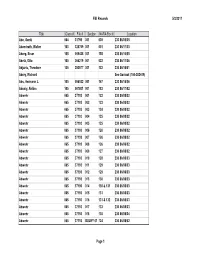

5/3/2011 FBI Records Page 1 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box

FBI Records 5/3/2011 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box # Location Abe, Genki 064 31798 001 039 230 86/05/05 Abendroth, Walter 100 325769 001 001 230 86/11/03 Aberg, Einar 105 009428 001 155 230 86/16/05 Abetz, Otto 100 004219 001 022 230 86/11/06 Abjanic, Theodore 105 253577 001 132 230 86/16/01 Abrey, Richard See Sovloot (100-382419) Abs, Hermann J. 105 056532 001 167 230 86/16/06 Abualy, Aldina 105 007801 001 183 230 86/17/02 Abwehr 065 37193 001 122 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 002 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 003 124 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 004 125 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 005 125 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 006 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 007 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 008 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 009 127 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 010 128 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 011 129 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 012 129 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 013 130 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 014 130 & 131 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 015 131 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 016 131 & 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 017 133 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 018 135 230 86/08/04 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 01 124 230 86/08/02 Page 1 FBI Records 5/3/2011 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box # Location Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 20 127 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 133 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 35 134 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 EBF 014X 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 EBF 014X 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr -

Modern History

MODERN HISTORY The Role of Youth Organisations in Nazi Germany: 1933-1939 It is often believed that children and adolescents are the most impressionable and vulnerable in society. Unlike adults, who have already developed their own established social views and political opinions, juveniles are still in the process of forming their attitudes and judgements on the world around them, so can easily be manipulated into following certain ideas and principles. This has been a fact widely taken advantage of by governments and political parties throughout history, in particular, by the Nazi Party under Adolf Hitler’s leadership between 1933 and 1939. The beginning of the 1930’s ushered in a new period of instability and uncertainty throughout Germany and with the slow but eventual collapse of the Weimar Government, as well as the start of the Great Depression, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) took the opportunity to gain a large and devoted following. This committed and loyal support was gained by appealing primarily to the industrial working class and the rural and farming communities, under the tenacious direction of nationalist politician Adolf Hitler. Through the use of powerful and persuasive propaganda, the Nazis presented themselves as ‘the party above class interests’1, a representation of hope, prosperity and unyielding leadership for the masses of struggling Germans. The appointment of NSDAP leader, Adolf Hitler, as chancellor of Germany on January 30th 1933, further cemented his reputation as the strong figure of guidance Germany needed to progress and prosper. On March 23rd 1933, the ‘Enabling Act’ was passed by a two thirds majority in the Reichstag, resulting in the suspension of the German Constitution and the rise of Hitler’s dictatorship. -

Parallel Journeys:Parallel Teacher’S Guide

Teacher’s Parallel Journeys: The Holocaust through the Eyes of Teens Guide GRADES 9 -12 Phone: 470 . 578 . 2083 historymuseum.kennesaw.edu Parallel Journeys: The Holocaust through the Eyes of Teens Teacher’s Guide Teacher’s Table of Contents About this Teacher’s Guide.............................................................................................................. 3 Overview ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Georgia Standards of Excellence Correlated with These Activities ...................................... 5 Guidelines for Teaching about the Holocaust .......................................................................... 12 CORE LESSON Understanding the Holocaust: “Tightening the Noose” – All Grades | 5th – 12th ............................ 15 5th Grade Activities 1. Individual Experiences of the Holocaust .......................................................................... 18 2. Propaganda and Dr. Seuss .................................................................................................. 20 3. Spiritual Resistance and the Butterfly Project .................................................................. 22 4. Responding to the St. Louis ............................................................................................... 24 5. Mapping the War and the Holocaust ................................................................................. 25 6th, 7th, and 8th Grade Activities -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-14571-8 - German Intellectuals and the Nazi Past A. Dirk Moses Excerpt More information Introduction The proposition that the Federal Republic of Germany has developed a healthy democratic culture centered around memory of the Holocaust has almost become a platitude.1 Symbolizing the relationship between the Federal Repub- lic’s liberal political culture and honest reckoning with the past, an enormous Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe adjacent to the Bundestag (Federal Parliament) and Brandenburg Gate in the national capital was unveiled in 2005. States usually erect monuments to their fallen soldiers, after all, not to the vic- tims of these soldiers. In the eyes of many, the West German and, since 1990, the united German experience has become the model of how post-totalitarian and postgenocidal societies “come to terms with the past.”2 Germany now seemed no different from the rest of Europe – or, indeed, from the West generally. Jews from Eastern Europe are as happy to settle there as they are to emigrate to Israel, the United States, or Australia.3 1 Bill Niven, Facing the Nazi Past: United Germany and the Legacy of the Third Reich (London and New York, 2002). For an excellent overview of postwar memory politics, see Andrew H. Beattie, “The Past in the Politics of Divided and Unified Germany,” in Max Paul Friedman and Padraic Kenney, eds., Partisan Histories: The Past in Contemporary Global Politics (Houndmills, 2005), 17–38. 2 For example, Daniel J. Goldhagen, “Modell Bundesrepublik: National History, Democracy and Internationalization in Germany,” Common Knowledge, 3 (1997), 10–18.