From Racial Selection to Postwar Deception

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tobacco Deal Sealed Prior to Global Finance Market Going up in Smoke

marketwatch KEY DEALS Tobacco deal sealed prior to global finance market going up in smoke The global credit crunch which so rocked £5.4bn bridging loan with ABN Amro, Morgan deal. “It had become an auction involving one or Iinternational capital markets this summer Stanley, Citigroup and Lehman Brothers. more possible white knights,” he said. is likely to lead to a long tail of negotiated and In addition it is rescheduling £9.2bn of debt – Elliott said the deal would be part-funded by renegotiated deals and debt issues long into both its existing commitments and that sitting on a large-scale disposal of Rio Tinto assets worth the autumn. the balance sheet of Altadis – through a new as much as $10bn. Rio’s diamonds, gold and But the manifestation of a bad bout of the facility to be arranged by Citigroup, Royal Bank of industrial minerals businesses are now wobbles was preceded by some of the Scotland, Lehmans, Barclays and Banco Santander. reckoned to be favourites to be sold. megadeals that the equity market had been Finance Director Bob Dyrbus said: Financing the deal will be new underwritten expecting for much of the last two years. “Refinancing of the facilities is the start of a facilities provided by Royal Bank of Scotland, One such long awaited deal was the e16.2bn process that is not expected to complete until the Deutsche Bank, Credit Suisse and Société takeover of Altadis by Imperial Tobacco. first quarter of the next financial year. Générale, while Deutsche and CIBC are acting as Strategically the Imps acquisition of Altadis “Imperial Tobacco only does deals that can principal advisors on the deal with the help of has been seen as the must-do in a global generate great returns for our shareholders and Credit Suisse and Rothschild. -

Lesson 12: Handout 4, Document 1 German Youth in the 1930S: Selected Excerpted Documents

Lesson 12: Handout 4, Document 1 German Youth in the 1930s: Selected excerpted documents Changes at School (Excerpted from “Changes at School,” pp. 175–76 in Facing History and Ourselves: Holocaust and Human Behavior ) Ellen Switzer, a student in Nazi Germany, recalls how her friend Ruth responded to Nazi antisemitic propaganda: Ruth was a totally dedicated Nazi. Some of us . often asked her how she could possibly have friends who were Jews or who had a Jewish background, when everything she read and distributed seemed to breathe hate against us and our ancestors. “Of course, they don’t mean you,” she would explain earnestly. “You are a good German. It’s those other Jews . who betrayed Germany that Hitler wants to remove from influence.” When Hitler actually came to power and the word went out that students of Jewish background were to be isolated, that “Aryan” Germans were no longer to associate with “non-Aryans” . Ruth actually came around and apologized to those of us to whom she was no longer able to talk. Not only did she no longer speak to the suddenly ostracized group of class - mates, she carefully noted down anybody who did, and reported them. 12 Purpose: To deepen understanding of how propaganda and conformity influence decision-making. • 186 Lesson 12: Handout 4, Document 2 German Youth in the 1930s: Selected excerpted documents Propaganda and Education (Excerpted from “Propaganda and Education,” pp. 242 –43 in Facing History and Ourselves: Holocaust and Human Behavior ) In Education for Death , American educator Gregor Ziemer described school - ing in Nazi Germany: A teacher is not spoken of as a teacher ( Lehrer ) but an Erzieher . -

The Fate of National Socialist Visual Culture: Iconoclasm, Censorship, and Preservation in Germany, 1945–2020

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Fall 1-5-2021 The Fate of National Socialist Visual Culture: Iconoclasm, Censorship, and Preservation in Germany, 1945–2020 Denali Elizabeth Kemper CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/661 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Fate of National Socialist Visual Culture: Iconoclasm, Censorship, and Preservation in Germany, 1945–2020 By Denali Elizabeth Kemper Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History, Hunter College The City University of New York 2020 Thesis sponsor: January 5, 2021____ Emily Braun_________________________ Date Signature January 5, 2021____ Joachim Pissarro______________________ Date Signature Table of Contents Acronyms i List of Illustrations ii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Points of Reckoning 14 Chapter 2: The Generational Shift 41 Chapter 3: The Return of the Repressed 63 Chapter 4: The Power of Nazi Images 74 Bibliography 93 Illustrations 101 i Acronyms CCP = Central Collecting Points FRG = Federal Republic of Germany, West Germany GDK = Grosse Deutsche Kunstaustellung (Great German Art Exhibitions) GDR = German Democratic Republic, East Germany HDK = Haus der Deutschen Kunst (House of German Art) MFAA = Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives Program NSDAP = Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Worker’s or Nazi Party) SS = Schutzstaffel, a former paramilitary organization in Nazi Germany ii List of Illustrations Figure 1: Anonymous photographer. -

Gemeinde Buchheim

48. JAHRGANG DONNERSTAG, 29. SEPTEMBER 2016 NUMMER 39 AMTSBLATT DER GEMEINDE BUCHHEIM Kinderferienprogramm - Freiwillige Feuerwehr Anwesend waren 14 Kinder die zunächst bei gutem Wetter unter An- leitung von Tatjana Hafner und Tanja Dedominicis die bereits durch die Feuerwehr vorbereiteteten Hydranten mit verschiedenen Moti- ven bemalten. Unterstützt von Angehörigen Feuerwehrfrauen wurde in kleinen Gruppen gearbeitet. Nebenbei boten die Feuerwehrmänner auf dem Hof beim Feuerwehrmagazin einen unterhaltsamen Parcours an. Neben beliebten Wasserspielen konnten die mutigen unter den Kids die Anhängeleiter besteigen. Geschicklichkeitsspiele und zu gu- ter letzt natürlich Rundfahrten mit dem Feuerwehrfahrzeug runde- ten das Angebot ab. Leider musste die Malaktion durch einsetzenden Regen abgebro- chen werden. Das angestrebte Ziel wurde daher nicht erreicht. Es sind noch zwei weitere Hydranten zu bemalen. Dies wird zu einem späteren Zeitpunkt entsprechend der Witterung dann kurzfristig nachgeholt. Ö"nungszeiten Rathaus: Mo - Mi 08.30 - 11.30 Uhr Do 15.00 - 18.00 Uhr Fr 08.30 - 11.30 Uhr Redaktion „donnerstags“ - wir sind erreichbar unter: Tel: 07777/311 F ax: 07777/1681 email: [email protected] oder [email protected] Backhaus Buchheim Sonderbacktag am Samstag, 08.10.2016 Am Samstag, 08.10.2016 wird das Backhaus in Buchheim außerplanmäßig angeheizt. Wer Lust und Interesse am Backen hat (Berufstätige, Neueinsteiger, sonstige Interessenten), ist ab 8.00 Uhr herzlich eingeladen. Das Einschießen !ndet um 9.45 Uhr statt. Bitte melden Sie sich bei Gemeindebackfrau Birgit Stoll an - Telefon: 01577/5980077 Donnerstag, den 29. September 2016 Seite 2 Die wichtigsten Telefonnummern auf einen Blick Bereitschaftsdienste Nachbarschaftshilfe von Haus zu Haus Monika Kohler Tel.07777/1732 Weitere Informationen erhalten Sie unter: www.hilfe-von-haus-zu-haus.de Caritas-Diakonie-Centrum Bergstr.14, 78532 Tuttlingen Tel. -

Wolfgang Stelbrink: Die Kreisleiter Der NSDAP in Westfalen Und Lippe

Die Kreisleiter der NSDAP in Westfalen und Lippe VERÖFFENTLICHUNGEN DER STAATLICHEN ARCHIVE DES LANDES NORDRHEIN-WESTFALEN REIHE C: QUELLEN UND FORSCHUNGEN BAND 48 IM AUFTRAG DES MINISTERIUMS FÜR STÄDTEBAU UND WOHNEN, KULTUR UND SPORT HERAUSGEGEBEN VOM NORDRHEIN-WESTFÄLISCHEN STAATSARCHIV MÜNSTER Die Kreisleiter der NSDAP in Westfalen und Lippe Versuch einer Kollektivbiographie mit biographischem Anhang von Wolfgang Stelbrink Münster 2003 Wolfgang Stelbrink Die Kreisleiter der NSDAP in Westfalen und Lippe Versuch einer Kollektivbiographie mit biographischem Anhang Münster 2003 Die Deutsche Bibliothek – CIP Eigenaufnahme Die Kreisleiter der NSDAP in Westfalen und Lippe im Auftr. des Ministeriums für Städtebau und Wohnung, Kultur und Sport des Landes Nordrhein-West- falen hrsg. vom Nordrhein-Westfälischen Staatsarchiv Münster. Bearb. von Wolfgang Stelbrink - Münster: Nordrhein-Westfälischen Staatsarchiv Münster, 2003 (Veröffentlichung der staatlichen Archive des Landes Nordrein-Westfalen: Reihe C, Quellen und Forschung; Bd. 48) ISBN: 3–932892–14–3 © 2003 by Nordrhein-Westfälischen Staatsarchiv, Münster Alle Rechte an dieser Buchausgabe vorbehalten, insbesondere das Recht des Nachdruckes und der fotomechanischen Wiedergabe, auch auszugsweise, des öffentlichen Vortrages, der Übersetzung, der Übertragung, auch einzelner Teile, durch Rundfunk und Fernsehen sowie der Übertragung auf Datenträger. Druck: DIP-Digital-Print, Witten Satz: Peter Fröhlich, NRW Staatsarchiv Münster Vertrieb: Nordrhein-Westfälischen Staatsarchiv Münster, Bohlweg 2, 48147 -

Arbeitsjubiläum Bei Der Firma Loma

AMTSBLATT 21. Januar 2016 Nr. 03 Arbeitsjubiläum bei der Firma Loma Im Rahmen der betrieblichen Weihnachtsfeier bei der Firma Loma konnte Frau Victoria Hohl und Herr Peter Dreher für 40-jährige Betriebszu- gehörigkeit geehrt werden. Im Namen des Ministerpräsidenten überbrachte der Schultes die Urkunde. Dabei lobte er die Leistung der Firma Loma und aller Mitarbeiter. Die Gemeinde lebe von solchen leistungsfähigen Firmen welche es ermöglichen, gute Rahmenbedingungen für das produzieren zu schafen und in der Gemeinde zu investieren. Um Erfolg zu haben, brauche es Motivation, Tatkraft und Überzeugung was man habe, wenn eine 40-jährige Betriebszugehörigkeit gefeiert werden kann. Herr Knaier berichtete von einem stabilen und guten Jahr 2015. BM Konstantin Braun: Brigitte Nann-Knaier; Peter Dreher; Victoria Hohl; Georg Knaier „DONNERSTAGS“ 21. Januar 2016 2 Sprechstunden des Bürgermeisters MITTEILUNGEN DES Die nächsten Sprechstunden des Bürgermeisters sind am Donnerstag, 21.1.2016 von 9.00 Uhr bis 11.30 Uhr BÜRGERMEISTERS Freitag, 22.1.2016 von 13.30 Uhr bis 15.00 Uhr Montag, 25.1.2016 von 10.30 Uhr bis 12.00 Uhr Dienstag, 26.1.2016 von 10.00 Uhr bis 12.00 Uhr Ich gratuliere Donnerstag, 28.1.2016 von 8.30 Uhr bis 12.00 Uhr Freitag, 29.1.2016 von 10.00 Uhr bis 12.00 Uhr Frau Dagmar Frech, Kapellenstraße 10 zum 75. Geburtstag am 21. Januar 2016 recht herzlich. Gerne helfe ich Ihnen, wenn Sie ein Anliegen haben. Am Dienstag, 26.1.2016 muß die Abendsprechstunde ausfallen weil ich einen an- Herzlichen Glückwunsch! deren dienstlichen Termin habe. Ich bin auch außerhalb dieser Zei- ten auf dem Rathaus. -

2016 Spring/Summer

SCHIFFER MILITARY New Books: 2 Aviation: 28 Naval: 54 Ground Forces: 56 American Civil War: 73 Militaria: 74 Modeling & Collectible Figures: 92 Pin-ups: 94 Transportation: 96 Index: 98 2016 Spring/Summer 2 2016 NEW BOOKS the 23rd waffen ss volunteer panzer grenadier division contents nederland 2016 new books 10 Enter the uavs: the 27th waffen ss the faa and volunteer drones in america grenadier division 7 langemarck 10 harriet quimby: training the right soldiers flying fair lady stuff: the at the doorstep: aircraft that civil war lore 4 produced america's jet 11 pilots 7 project mercury: suppliers to the matterhorn—the america in space confederacy, v. ii operational history series of the us xx bomber 11 command from india 8 and china, 1944–1945 5 project gemini: last ride of the a pictorial history america in space valkyries: the rise of the b-2a series and fall of the spirit stealth wehrmachthelfer- bomber 8 innenkorps during 5 wwii 12 the history of the german u-boat waffen-ss dyess air force base at lorient, camouflage base, 1941 to the france, august 1942– uniforms, vol. 1 present august 1943, vol. 3 13 6 9 german u-boat ace waffen-ss jet city rewind: peter cremer: camouflage the patrols of aviation history uniforms, vol. 2 u-333 in of seattle and the world war ii pacific northwest 13 6 9 2016 NEW BOOKS 3 german military travel papers of the second world war 14 united states american the model 1891 navy helicopter heroes quilts, carcano rifle patches past and present 24 15 19 united states mitchell’s new a collector’s marine corps general atlas guide to the emblems: 1804 to 1860 savage 99 rifle world war i 20 15 25 privateers american ferrer-dalmau: of the revolution: breechloading art, history, and war on the new mobile artillery miniatures jersey coast, 1875–1953 1775–1783 21 26 16 fighting for making leather bombshell: uncle sam: knife sheaths, the pin-up art of buffalo soldiers vol. -

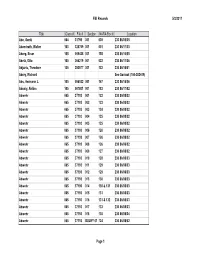

5/3/2011 FBI Records Page 1 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box

FBI Records 5/3/2011 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box # Location Abe, Genki 064 31798 001 039 230 86/05/05 Abendroth, Walter 100 325769 001 001 230 86/11/03 Aberg, Einar 105 009428 001 155 230 86/16/05 Abetz, Otto 100 004219 001 022 230 86/11/06 Abjanic, Theodore 105 253577 001 132 230 86/16/01 Abrey, Richard See Sovloot (100-382419) Abs, Hermann J. 105 056532 001 167 230 86/16/06 Abualy, Aldina 105 007801 001 183 230 86/17/02 Abwehr 065 37193 001 122 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 002 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 003 124 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 004 125 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 005 125 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 006 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 007 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 008 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 009 127 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 010 128 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 011 129 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 012 129 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 013 130 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 014 130 & 131 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 015 131 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 016 131 & 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 017 133 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 018 135 230 86/08/04 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 01 124 230 86/08/02 Page 1 FBI Records 5/3/2011 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box # Location Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 20 127 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 133 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 35 134 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 EBF 014X 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 EBF 014X 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr -

Modern History

MODERN HISTORY The Role of Youth Organisations in Nazi Germany: 1933-1939 It is often believed that children and adolescents are the most impressionable and vulnerable in society. Unlike adults, who have already developed their own established social views and political opinions, juveniles are still in the process of forming their attitudes and judgements on the world around them, so can easily be manipulated into following certain ideas and principles. This has been a fact widely taken advantage of by governments and political parties throughout history, in particular, by the Nazi Party under Adolf Hitler’s leadership between 1933 and 1939. The beginning of the 1930’s ushered in a new period of instability and uncertainty throughout Germany and with the slow but eventual collapse of the Weimar Government, as well as the start of the Great Depression, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) took the opportunity to gain a large and devoted following. This committed and loyal support was gained by appealing primarily to the industrial working class and the rural and farming communities, under the tenacious direction of nationalist politician Adolf Hitler. Through the use of powerful and persuasive propaganda, the Nazis presented themselves as ‘the party above class interests’1, a representation of hope, prosperity and unyielding leadership for the masses of struggling Germans. The appointment of NSDAP leader, Adolf Hitler, as chancellor of Germany on January 30th 1933, further cemented his reputation as the strong figure of guidance Germany needed to progress and prosper. On March 23rd 1933, the ‘Enabling Act’ was passed by a two thirds majority in the Reichstag, resulting in the suspension of the German Constitution and the rise of Hitler’s dictatorship. -

3) KONTROLLE UND EINSCHÜCHTERUNG Mag

1 WAIDHOFEN 1938 - 1945 3) KONTROLLE UND EINSCHÜCHTERUNG Mag. Walter Zambal INHALT: 1) DIE MACHTÜBERNAHME DURCH DIE NSDAP 2) DIE TOTALE ERFASSUNG DER BEVÖLKERUNG 3) DENUNZIATIONEN 4) DER „BOTE VON DER YBBS“ ALS INSTRUMENT DER EINSCHÜCHTERUNG 5) DIE VERSCHÄRFUNG DER SITUATION GEGEN ENDE DES KRIEGES 6) LITERATUR- UND QUELLENVERZEICHNIS 7) ANHANG 1) DIE MACHTÜBERNAHME DURCH DIE NSDAP Nach dem Anschluss wird die Einheitspartei des Ständestaates, die „Vaterländische Front“ sofort aufgelöst. Als nunmehr einzige Partei ist die NSDAP (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei) mit ihren Gliederungen und angeschlossenen Verbänden zugelassen. Aber bereits vor dem Anschluss gibt es in Waidhofen 271 „organisierte Parteigenossen“, wie aus einem Artikel im „Boten“ vom 25.März 1938 hervorgeht: ► „Die ‚paar jugendlichen Unentwegten’, wie es immer hieß, umfaßten in unserer Stadt die stattliche Zahl von 271 organisierten Parteigenossen, davon in der SS 33, SA 106, NSKK 44, PO 106, HJ 88, BDM 24, NSF 50.“1 Noch im Juni 1938 kommt es zu einer „Vergeltungsaktion“ die gegen die Vertreter des Ständestaates gerichtet ist: ► Inspektor Pitzel berichtet über Vergeltungsmaßnahmen der SA im Juni 1938: „Im Juni inszenierte die SA eines Abends schlagartig eine sogenannte Vergeltungsaktion, bei der ihr mißliebige Gegner, hauptsächlich solche, welche in den ehemaligen Wehrformationen sich hervorgetan hatten, aus den Wohnungen geholt und zur Polizeidienststelle gebracht wurden. Dort hatte sich eine große Menschenmenge angesammelt, die an den Vorgängen anscheinend Gefallen fand. Mehrere der unrechtmäßig Festgenommenen wurden insultiert, einige nicht unerheblich verletzt.“2 Diese Vorfälle werden auch im Situationsbericht des Landrats des Kreises Amstetten an die Gestapo Wien vom 1.7.1938 erwähnt: „Der Monat Juni (1938) ist im Bezirke im allgemeinen politisch vollkommen ruhig verlaufen. -

United States

Cultural Policy and Political Oppression: Nazi Architecture and the Development of SS Forced Labor Concentration Camps* Paul B. Jaskot Beyond its use as propaganda, art was thoroughly integrated into the implementation of Nazi state and party policies. Because artistic and political goals were integrated, art was not only subject to repressive policies but also in turn influenced the formulation of those very repressive measures. In the Third Reich, art policy was increasingly authoritarian in character; however, art production also became one means by which other authoritarian institutions could develop their ability to oppress. The Problem We can analyze the particular political function of art by looking at the interest of the SS in orienting its forced labor operations to the monumental building economy. The SS control of forced labor concentration camps after 1936 linked state architectural policy to the political function of incarcerating and punishing perceived enemies of National Socialist Germany.1 The specific example of the Nuremberg Reich Party Rally Grounds reveals three key aspects of this SS process of adaptation. The first aspect is the relationship between architectural decisions at Nuremberg and developments in the German building economy during the early war years. Before the turning tide of the war led to a cessation of work at the site, agencies and firms involved with the design and construction of the Nuremberg buildings secured a steady and profitable supply of work as a result of Hitler’s emphasis on a few large architectural projects. The second aspect focuses on how the SS quarrying enterprises in the forced labor concentration camps were comparable to their private-sector competitors. -

Foundations of Nazi Cultural Policy and Institutions Responsible for Its

Kultura i Edukacja 2014 No 6 (106), s. 173–192 DOI: 10.15804/kie.2014.06.10 www.kultura-i-edukacja.pl Sylwia Grochowina, Katarzyna Kącka1 Foundations of Nazi Cultural Policy and Institutions Responsible for its Implementation in the Period 1933 – 1939 Abstract The purpose of this article is to present and analyze the foundations and premises of Nazi cultural policy, and the bodies responsible for its imple- mentation, the two most important ones being: National Socialist Society for German Culture and the Ministry of National Enlightenment and Propa- ganda of the Reich. Policy in this case is interpreted as intentional activity of the authorities in the field of culture, aimed at influencing the attitudes and identity of the population of the Third Reich. The analysis covers the most important documents, statements and declarations of politicians and their actual activity in this domain. Adopting such a broad perspective al- lowed to comprehensively show both the language and the specific features of the messages communicated by the Nazi authorities, and its impact on cultural practices. Key words Third Reich, Nazi, cultural policy, National Socialist Society for German Culture, Ministry of National Enlightenment and Propaganda of the Reich 1 Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, Polnad 174 Sylwia Grochowina, Katarzyna Kącka 1. INTRODUCTION The phenomenon of culture is one of the most important distinctive features of individual societies and nations. In a democratic social order, creators of culture can take full advantage of creative freedom, while the public can choose what suits them best from a wide range of possibilities. Culture is also a highly variable phenomenon, subject to various influences.