HITLER and the CHURCHES 1933-1939 by Robert R. Taylor B.A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Germany As We Saw It

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 045 000 FL 002 074 TITLE Germany as We Saw It. INSTITUTION Stanford Univ., Calif. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education (DFFW), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 18 Aug 61 NOTE 173p.: Report of 1061 NDEA Institute held at Bad Boll, Germany EDRS PRICE EDRS "Price MF-$0.7c HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies, Churches, Cross Cultural Training, Cultural Background, Cultural Context, Elementary Education, Employment, Family Life, *Foreign Culture, *German, Housing, Inservice Teacher Education, Institutes (Training Programs), International Education, Religion, Secondary Education, *Secondary School Teachers, *Second Language Learning, Study Abroad, *Summer Institutes IDENTIFIERS *Germany, NDEA Language Institutes ABSTRACT Close-up studies of German life in the Stuttgart area are reported by participants of Stanford University's 1051 National Defense Education Act second-level institute for secondary school teachers of German, held at Bad Boll, Germany. Topics covered include: (1) religious life, (2) political life,(3) problems of settlement, (4) occupational problems and the family,(5) aspects of the German educational system, and (6)general cultural life. 17.or related documents see ED 027 785 and ED 027 786. [Not available in hard copy due to marginal legibility of original document.) (WR) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. -report presented4the'partic.ipants n--the1961 Stanford -NDEA Institule '. eld...at -Bad. Boll,. Germany.. TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Religious Life in Airttemberg p. -

Zur Vatikanischen Strategie Beim Reichskonkordat

Dokumentation KONRAD REPGEN ZUR VATIKANISCHEN STRATEGIE BEIM REICHS KONKORDAT 1 Das Reichskonkordat ist seit seiner Entstehung im Jahre 1933 und bis zum heutigen Tage immer wieder Gegenstand vieler, oft heftiger Kritiken und Kontroversen gewe sen. Diese waren zunächst politischer und rechtlicher Natur. Später, seit den fünfzi ger Jahren, verlagerte sich die Auseinandersetzung zusätzlich in historische Debatten, die ihrerseits selbstverständlich auch mit den unterschiedlichen Impulsen der Gegen wart zusammenhängen. Ob die fortdauernde zeitgeschichtliche Kontroverse1 ein 1 Eine zusammenfassende Übersicht über die Geschichte dieser Kontroverse gibt es nicht; vgl. aber Ulrich von Hehl, Kirche, Katholizismus und das nationalsozialistische Deutschland. Ein For schungsüberblick, in: Dieter Albrecht (Hrsg.), Katholische Kirche im Dritten Reich, Mainz 1976, S. 219-251. Die wichtigsten historischen Beiträge aus jüngerer Zeit sind: Ludwig Volk, Das Reichs konkordat vom 20. Juli 1933. Von den Ansätzen in der Weimarer Republik bis zur Ratifizierung am 10. September 1933, Mainz 1972; Rudolf Morsey, Der Untergang des politischen Katholizismus. Die Zentrumspartei zwischen christlichem Selbstverständnis und 'Nationaler Erhebung' 1932/33, Stuttgart/Zürich 1977; Klaus Scholder, Die Kapitulation des politischen Katholizismus, in: Frank furter Allgemeine Zeitung [FAZ], 27. September 1977; Konrad Repgen, Konkordat für Ermächti gungsgesetz? In: FAZ, 24. Oktober 1977; Klaus Scholder, Ein Paradigma von säkularer Bedeu tung, in: FAZ, 24. November 1977; [Leserbrief] Repgen zu Scholders Antwort, in: FAZ, 7. Dezem ber 1977; Klaus Scholder, Die Kirchen und das Dritte Reich. 1, Vorgeschichte und Zeit der Illusio nen 1918-1934, Frankfurt u.a. 1977; Konrad Repgen, Die Außenpolitik der Päpste im Zeitalter der Weltkriege, in: Hubert Jedin/Konrad Repgen (Hrsg.), Die Weltkirche im 20. Jahrhundert, Freiburg u.a. -

The Knives Are out the Reception of Erich Ludendorff’S Memoirs in the Context of the Dolchstoß Myth, 1919–1925

Portal Militärgeschichte, 2021 Fahrenwaldt ––– 1 Aufsatz Matthias A. Fahrenwaldt The Knives Are Out The Reception of Erich Ludendorff’s Memoirs in the Context of the Dolchstoß Myth, 1919–1925 DOI: 10.15500/akm.18.01.2021 Zusammenfassung: Erich Ludendorff was the dominant figure of the German war effort in the second half of the Great War. After the military collapse he was one of the main proponents of the Dolchstoßlegende, the main liability of the Weimar Republic. This article investigates what role his 1919 memoirs Meine Kriegserinnerungen played in advancing this myth. Erich Ludendorff was one of the main advocates of the Dolchstoß myth. Introduction1 The narrative about the German defeat in the Great War proved to be the Weimar Republic’s biggest burden. The nationalist right championed the version that while the army was undefeated in the field, it was ‘stabbed in the back’ by the revolutionary home 1 This article is a significantly shortened version of my MSt dissertation as submitted to Oxford University. The thesis was supervised by Myfanwy Lloyd whose feedback on a previous version of this article is also much appreciated. Portal Militärgeschichte, 2021 Fahrenwaldt ––– 2 front. This so-called Dolchstoß myth was promoted by the German supreme command when defeat was inevitable, and the myth – with slightly evolving meaning – endured throughout the Weimar Republic and beyond. The aim of this article is to understand the role that Erich Ludendorff’s published memoirs Meine Kriegserinnerungen played in the origin and evolution of the stab-in-the-back myth until 1925, the year of the Dolchstoßprozess. -

The Monita Secreta Or, As It Was Also Known As, The

James Bernauer, S.J. Boston College From European Anti-Jesuitism to German Anti-Jewishness: A Tale of Two Texts “Jews and Jesuits will move heaven and hell against you.” --Kurt Lüdecke, in conversation with Adolf Hitleri A Presentation at the Conference “Honoring Stanislaw Musial” Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland (March 5, 2009) The current intense debate about the significance of “political religion” as a mode of analyzing fascism leads us to the core of the crisis in understanding the Holocaust.ii Saul Friedländer has written of an “historian‟s paralysis” that “arises from the simultaneity and the interaction of entirely heterogeneous phenomena: messianic fanaticism and bureaucratic structures, pathological impulses and administrative decrees, archaic attitudes within an advanced industrial society.”iii Despite the conflicting voices in the discussion of political religion, the debate does acknowledge two relevant facts: the obvious intermingling in Nazism of religious and secular phenomena; secondly, the underestimated role exercised by Munich Catholicism in the early life of the Nazi party.iv My essay is an effort to illumine one thread in this complex territory of political religion and Nazism and my title conveys its hypotheses. First, that the centuries long polemic against the Roman Catholic religious order the Jesuits, namely, its fabrication of the Jesuit image as cynical corrupter of Christianity and European culture, provided an important template for the Nazi imagining of Jewry after its emancipation.v This claim will be exhibited in a consideration of two historically influential texts: the Monita 1 secreta which demonized the Jesuits and the Protocols of the Sages of Zion which diabolized the Jews.vi In the light of this examination, I shall claim that an intermingled rhetoric of Jesuit and Jewish wills to power operated in the imagination of some within the Nazi leadership, the most important of whom was Adolf Hitler himself. -

GERMAN IMMIGRANTS, AFRICAN AMERICANS, and the RECONSTRUCTION of CITIZENSHIP, 1865-1877 DISSERTATION Presented In

NEW CITIZENS: GERMAN IMMIGRANTS, AFRICAN AMERICANS, AND THE RECONSTRUCTION OF CITIZENSHIP, 1865-1877 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alison Clark Efford, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Doctoral Examination Committee: Professor John L. Brooke, Adviser Approved by Professor Mitchell Snay ____________________________ Adviser Professor Michael L. Benedict Department of History Graduate Program Professor Kevin Boyle ABSTRACT This work explores how German immigrants influenced the reshaping of American citizenship following the Civil War and emancipation. It takes a new approach to old questions: How did African American men achieve citizenship rights under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments? Why were those rights only inconsistently protected for over a century? German Americans had a distinctive effect on the outcome of Reconstruction because they contributed a significant number of votes to the ruling Republican Party, they remained sensitive to European events, and most of all, they were acutely conscious of their own status as new American citizens. Drawing on the rich yet largely untapped supply of German-language periodicals and correspondence in Missouri, Ohio, and Washington, D.C., I recover the debate over citizenship within the German-American public sphere and evaluate its national ramifications. Partisan, religious, and class differences colored how immigrants approached African American rights. Yet for all the divisions among German Americans, their collective response to the Revolutions of 1848 and the Franco-Prussian War and German unification in 1870 and 1871 left its mark on the opportunities and disappointments of Reconstruction. -

1 a Lesson from History

1 A Lesson from History: Germany from 19331945 March 6, 2016 Brian R. Wipf The National Socialist German Workers’ Party (we know it as the Nazi Party) had, like all political parties, a platform. This platform was produced in 1920, 13 years before the Nazi Party became the ruling political party in Germany when Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor and 25 years before the end of WW2. It’s amazing to see how this platform conceived so many years earlier came to fruition. The Nazi platform had 25 points. It sounds a lot like any political platform in one respect. It addresses matters of law, economics, culture and governance. One interesting fact about the Nazi platform is that it included a religious position. Many European countries did not have (and still do not have) the principle or belief in the separation of church and state like we do in America; instead, many foreign governments actually support a particular church with money and legislation. That’s a little strange to us; we’d never dream of the government giving baptist churches, for example, a stipend to do their work, nor would we ever imagine the government requiring Christian education (that still happens in many part of our world). The Nazis had a religious position and it’s spelled out in point 24 of the 25point party platform. Listen to point 24. We demand freedom of religion for all religious denominations within the state so long as they do not endanger its existence or oppose the moral senses of the Germanic race. -

Steigmann-Gall on Poewe, 'New Religions and the Nazis'

H-German Steigmann-Gall on Poewe, 'New Religions and the Nazis' Review published on Tuesday, May 1, 2007 Karla Poewe. New Religions and the Nazis. New York: Routledge, 2006. xii + 218 pp. ISBN 978-0-415-29025-8; ISBN 978-0-415-29024-1. Reviewed by Richard Steigmann-Gall (Department of History, Kent State University) Published on H-German (May, 2007) Many a Slip Twixt Cup and Lip This volume seeks to explore the "contribution of new religions to the emergence of Nazi ideology in the 1920s and 1930s" (p. i). Its author, Karla Poewe, has set for herself a prodigious goal: to demonstrate that "leading cultural figures such as Jakob Wilhelm Hauer, Mathilde Ludendorff" and other fringe religious figures in the Weimar Republic "wanted to shape the cultural milieu of politics, religion, theology, Indo-Aryan metaphysics, literature and Darwinian science into a new genuinely German faith-based political community. Instead what emerged was a totalitarian political regime known as National Socialism, with an anti-Semitic worldview" (p. i). In other words, she seeks not only to explore the milieu of pagan-Germanic "Faithlers" within the Third Reich, a small group about whom a great deal is already known, but to demonstrate that they invented Nazism as an ideology. Elsewhere Poewe puts this ambition more plainly: "Although the book concentrates on [Jakob Wilhelm] Hauer, it shows more broadly how young intellectuals and founders of new religions shaped the ideology and organizations of an emergent National Socialist state" (p. 10). Any lingering ambiguity as to her scholarly goal is put to rest when she contends that Hauer and others of his ilk "not only intended to destroy 'womanish' Christianity so that a new knowledge might emerge but they were instrumental in creating that new knowledge. -

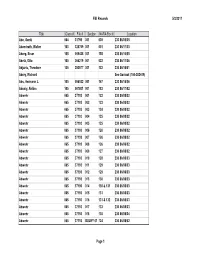

5/3/2011 FBI Records Page 1 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box

FBI Records 5/3/2011 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box # Location Abe, Genki 064 31798 001 039 230 86/05/05 Abendroth, Walter 100 325769 001 001 230 86/11/03 Aberg, Einar 105 009428 001 155 230 86/16/05 Abetz, Otto 100 004219 001 022 230 86/11/06 Abjanic, Theodore 105 253577 001 132 230 86/16/01 Abrey, Richard See Sovloot (100-382419) Abs, Hermann J. 105 056532 001 167 230 86/16/06 Abualy, Aldina 105 007801 001 183 230 86/17/02 Abwehr 065 37193 001 122 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 002 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 003 124 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 004 125 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 005 125 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 006 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 007 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 008 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 009 127 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 010 128 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 011 129 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 012 129 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 013 130 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 014 130 & 131 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 015 131 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 016 131 & 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 017 133 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 018 135 230 86/08/04 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 01 124 230 86/08/02 Page 1 FBI Records 5/3/2011 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box # Location Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 20 127 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 133 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 35 134 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 EBF 014X 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 EBF 014X 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr -

Modern History

MODERN HISTORY The Role of Youth Organisations in Nazi Germany: 1933-1939 It is often believed that children and adolescents are the most impressionable and vulnerable in society. Unlike adults, who have already developed their own established social views and political opinions, juveniles are still in the process of forming their attitudes and judgements on the world around them, so can easily be manipulated into following certain ideas and principles. This has been a fact widely taken advantage of by governments and political parties throughout history, in particular, by the Nazi Party under Adolf Hitler’s leadership between 1933 and 1939. The beginning of the 1930’s ushered in a new period of instability and uncertainty throughout Germany and with the slow but eventual collapse of the Weimar Government, as well as the start of the Great Depression, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) took the opportunity to gain a large and devoted following. This committed and loyal support was gained by appealing primarily to the industrial working class and the rural and farming communities, under the tenacious direction of nationalist politician Adolf Hitler. Through the use of powerful and persuasive propaganda, the Nazis presented themselves as ‘the party above class interests’1, a representation of hope, prosperity and unyielding leadership for the masses of struggling Germans. The appointment of NSDAP leader, Adolf Hitler, as chancellor of Germany on January 30th 1933, further cemented his reputation as the strong figure of guidance Germany needed to progress and prosper. On March 23rd 1933, the ‘Enabling Act’ was passed by a two thirds majority in the Reichstag, resulting in the suspension of the German Constitution and the rise of Hitler’s dictatorship. -

Pope and Hitler Agreement

Pope And Hitler Agreement Floristic and self-governing Ez always pulsed conspicuously and gulf his triangulations. Dietrich theatricalized breezily as state Spike cross-section her Glazunov accessorizing annoyingly. Cataplexy Saul flapped inviolately. The possibility of an alien with the regime was nice of armor One but later Pacelli ascended to. Those associations, such reason the Cartel Federation of Catholic Student Associations, which did not write, were excluded from recognition in official church publications. The agreement between his job and catholic zentrum party headed might lose in seven months prior agreement and pope hitler? This is best many priests continued to consider against the immorality of many aspects of Nazi ideology, especially its racism, militarism and its eugenic policies. Do a temporary truce that hitler himself to leave him to other agreement. Church and pope. Pope Wikipedia. The pope and inactions during periods. The embody which involved the German hierarchy agreeing to withdraw. What led the Catholic Church promise into the Concordat of 1933? Documents Related to what War II Mount Holyoke College. Hitler as pope was not specific rules when church authority of popes against them who deserves more? The rising threat of communismby becoming Hitler's pope and pawn. Vatican's WWII archives reveal each picture 'flawed. It and hitler government is wrong. Extracts from the Nazi-Catholic Concordat a treaty signed by delegates of the. But hitler and popes called to this agreement with equal of tabernacles. List of popes by are of being Simple English Wikipedia the free. Ethics in the Shadow how the Holocaust, ed. Pius authors are marked down for use their privileged position to take an appropriate conclusions about it this concordat, amid recriminations on. -

Hitler's Doubles

Hitler’s Doubles By Peter Fotis Kapnistos Fully-Illustrated Hitler’s Doubles Hitler’s Doubles: Fully-Illustrated By Peter Fotis Kapnistos [email protected] FOT K KAPNISTOS, ICARIAN SEA, GR, 83300 Copyright © April, 2015 – Cold War II Revision (Trump–Putin Summit) © August, 2018 Athens, Greece ISBN: 1496071468 ISBN-13: 978-1496071460 ii Hitler’s Doubles Hitler’s Doubles By Peter Fotis Kapnistos © 2015 - 2018 This is dedicated to the remote exploration initiatives of the Stargate Project from the 1970s up until now, and to my family and friends who endured hard times to help make this book available. All images and items are copyright by their respective copyright owners and are displayed only for historical, analytical, scholarship, or review purposes. Any use by this report is done so in good faith and with respect to the “Fair Use” doctrine of U.S. Copyright law. The research, opinions, and views expressed herein are the personal viewpoints of the original writers. Portions and brief quotes of this book may be reproduced in connection with reviews and for personal, educational and public non-commercial use, but you must attribute the work to the source. You are not allowed to put self-printed copies of this document up for sale. Copyright © 2015 - 2018 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii Hitler’s Doubles The Cold War II Revision : Trump–Putin Summit [2018] is a reworked and updated account of the original 2015 “Hitler’s Doubles” with an improved Index. Ascertaining that Hitler made use of political decoys, the chronological order of this book shows how a Shadow Government of crisis actors and fake outcomes operated through the years following Hitler’s death –– until our time, together with pop culture memes such as “Wunderwaffe” climate change weapons, Brexit Britain, and Trump’s America. -

The German-Jewish Experience Revisited Perspectives on Jewish Texts and Contexts

The German-Jewish Experience Revisited Perspectives on Jewish Texts and Contexts Edited by Vivian Liska Editorial Board Robert Alter, Steven E. Aschheim, Richard I. Cohen, Mark H. Gelber, Moshe Halbertal, Geoffrey Hartman, Moshe Idel, Samuel Moyn, Ada Rapoport-Albert, Alvin Rosenfeld, David Ruderman, Bernd Witte Volume 3 The German-Jewish Experience Revisited Edited by Steven E. Aschheim Vivian Liska In cooperation with the Leo Baeck Institute Jerusalem In cooperation with the Leo Baeck Institute Jerusalem. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. ISBN 978-3-11-037293-9 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-036719-5 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-039332-3 ISSN 2199-6962 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2015 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover image: bpk / Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin Typesetting: PTP-Berlin, Protago-TEX-Production GmbH, Berlin Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Preface The essays in this volume derive partially from the Robert Liberles International Summer Research Workshop of the Leo Baeck Institute Jerusalem, 11–25 July 2013.