Update: Investigation of Bioterrorism-Related Anthrax and Interim Guidelines for Exposure Management and Antimicrobial Therapy, October 2001

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amerithrax Investigative Summary

The United States Department of Justice AMERITHRAX INVESTIGATIVE SUMMARY Released Pursuant to the Freedom of Information Act Friday, February 19, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. THE ANTHRAX LETTER ATTACKS . .1 II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . 4 A. Overview of the Amerithrax Investigation . .4 B. The Elimination of Dr. Steven J. Hatfill as a Suspect . .6 C. Summary of the Investigation of Dr. Bruce E. Ivins . 6 D. Summary of Evidence from the Investigation Implicating Dr. Ivins . .8 III. THE AMERITHRAX INVESTIGATION . 11 A. Introduction . .11 B. The Investigation Prior to the Scientific Conclusions in 2007 . 12 1. Early investigation of the letters and envelopes . .12 2. Preliminary scientific testing of the Bacillus anthracis spore powder . .13 3. Early scientific findings and conclusions . .14 4. Continuing investigative efforts . 16 5. Assessing individual suspects . .17 6. Dr. Steven J. Hatfill . .19 7. Simultaneous investigative initiatives . .21 C. The Genetic Analysis . .23 IV. THE EVIDENCE AGAINST DR. BRUCE E. IVINS . 25 A. Introduction . .25 B. Background of Dr. Ivins . .25 C. Opportunity, Access and Ability . 26 1. The creation of RMR-1029 – Dr. Ivins’s flask . .26 2. RMR-1029 is the source of the murder weapon . 28 3. Dr. Ivins’s suspicious lab hours just before each mailing . .29 4. Others with access to RMR-1029 have been ruled out . .33 5. Dr. Ivins’s considerable skill and familiarity with the necessary equipment . 36 D. Motive . .38 1. Dr. Ivins’s life’s work appeared destined for failure, absent an unexpected event . .39 2. Dr. Ivins was being subjected to increasing public criticism for his work . -

Investigation of Anthrax Associated with Intentional Exposure

October 19, 2001 / Vol. 50 / No. 41 889 Update: Investigation of Anthrax Associated with Intentional Exposure and Interim Public Health Guidelines, October 2001 893 Recognition of Illness Associated with the Intentional Release of a Biologic Agent 897 Weekly Update: West Nile Virus Activity — United States, October 10–16, 2001 Update: Investigation of Anthrax Associated with Intentional Exposure and Interim Public Health Guidelines, October 2001 On October 4, 2001, CDC and state and local public health authorities reported a case of inhalational anthrax in Florida (1 ). Additional cases of anthrax subsequently have been reported from Florida and New York City. This report updates the findings of these case investigations, which indicate that infections were caused by the intentional release of Bacillus anthracis. This report also includes interim guidelines for postexposure pro- phylaxis for prevention of inhalational anthrax and other information to assist epidemi- ologists, clinicians, and laboratorians responding to intentional anthrax exposures. For these investigations, a confirmed case of anthrax was defined as 1) a clinically compatible case of cutaneous, inhalational, or gastrointestinal illness* that is laboratory confirmed by isolation of B. anthracis from an affected tissue or site or 2) other labora- tory evidence of B. anthracis infection based on at least two supportive laboratory tests. A suspected case was defined as 1) a clinically compatible case of illness without isola- tion of B. anthracis and no alternative diagnosis, but with laboratory evidence of B. anthracis by one supportive laboratory test or 2) a clinically compatible case of an- thrax epidemiologically linked to a confirmed environmental exposure, but without cor- roborative laboratory evidence of B. -

Drug-Resistant Streptococcus Pneumoniae and Methicillin

NEWS & NOTES Conference Summary pneumoniae can vary among popula- conference sessions was that statically tions and is influenced by local pre- sound methods of data collection that Drug-resistant scribing practices and the prevalence capture valid, meaningful, and useful of resistant clones. Conference pre- data and meet the financial restric- Streptococcus senters discussed the role of surveil- tions of state budgets are indicated. pneumoniae and lance in raising awareness of the Active, population-based surveil- Methicillin- resistance problem and in monitoring lance for collecting relevant isolates is the effectiveness of prevention and considered the standard criterion. resistant control programs. National- and state- Unfortunately, this type of surveil- Staphylococcus level epidemiologists discussed the lance is labor-intensive and costly, aureus benefits of including state-level sur- making it an impractical choice for 1 veillance data with appropriate antibi- many states. The challenges of isolate Surveillance otic use programs designed to address collection, packaging and transport, The Centers for Disease Control the antibiotic prescribing practices of data collection, and analysis may and Prevention (CDC) convened a clinicians. The potential for local sur- place an unacceptable workload on conference on March 12–13, 2003, in veillance to provide information on laboratory and epidemiology person- Atlanta, Georgia, to discuss improv- the impact of a new pneumococcal nel. ing state-based surveillance of drug- vaccine for children was also exam- Epidemiologists from several state resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae ined; the vaccine has been shown to health departments that have elected (DRSP) and methicillin-resistant reduce infections caused by resistance to implement enhanced antimicrobial Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). -

2001 Anthrax Letters

Chapter Five: 2001 Anthrax Letters Author’s Note: The analysis and comments regarding the communication efforts described in this case study are solely those of the authors; this analysis does not represent the official position of the FDA. This case was selected because it is one of the few major federal efforts to distribute medical countermeasures in response to an acute biological incident. These events occurred more than a decade ago and represent the early stages of US biosecurity preparedness and response; however, this incident serves as an excellent illustration of the types of communication challenges expected in these scenarios. Due in part to the extended time since these events and the limited accessibility of individual communications and messages, this case study does not provide a comprehensive assessment of all communication efforts. In contrast to the previous case studies in this casebook, the FDA’s role in the 2001 anthrax response was relatively small, and as such, this analysis focuses principally on the communication efforts of the CDC and state and local public health agencies. The 2001 anthrax attacks have been studied extensively, and the myriad of internal and external assessments led to numerous changes to response and communications policies and protocols. The authors intend to use this case study as a means of highlighting communication challenges strictly within the context of this incident, not to evaluate the success or merit of changes made as a result of these events. Abstract The dissemination of Bacillus anthracis via the US Postal Service (USPS) in 2001 represented a new public health threat, the first intentional exposure to anthrax in the United States. -

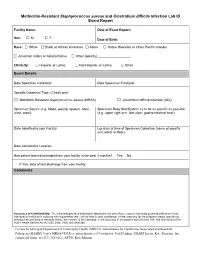

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus and Clostridium Difficile Infection Lab ID Event Report

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Clostridium difficile Infection Lab ID Event Report Facility Name: Date of Event Report: Sex: M F □ □ Date of Birth: Race: □ White □ Black or African American □ Asian □ Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander □ American Indian or Alaska Native □ Other [specify] __________________ Ethnicity: □ Hispanic or Latino □ Not Hispanic or Latino □ Other Event Details Date Specimen Collected: Date Specimen Finalized: Specific Organism Type: (Check one) □ Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) □ Clostridium difficile Infection (CDI) Specimen Source (e.g. blood, wound, sputum, bone, Specimen Body Site/System try to be as specific as possible urine, stool): (e.g. upper right arm, foot ulcer, gastrointestinal tract): Date Admitted to your Facility: Location at time of Specimen Collection (name of specific unit, ward, or floor): Date Admitted to Location: Has patient been discharged from your facility in the past 3 months? Yes No If Yes, date of last discharge from your facility: Comments Assurance of Confidentiality: The voluntarily provided information obtained in this surveillance system that would permit identification of any individual or institution is collected with a guarantee that it will be held in strict confidence, will be used only for the purposes stated, and will not otherwise be disclosed or released without the consent of the individual, or the institution in accordance with Sections 304, 306 and 308(d) of the Public Health Service Act (42 USC 242b, 242k, and 242m(d)). For use by Michigan Department of Community Health (MDCH), Surveillance for Healthcare-Associated and Resistant Pathogens (SHARP) Unit’s MRSA/CDI Prevention Initiative (Coordinator: Gail Denkins, SHARP Intern: Kate Manton); fax completed forms to (517) 335-8263, ATTN: Kate Manton. -

Association Between Carriage of Streptococcus Pneumoniae and Staphylococcus Aureus in Children

BRIEF REPORT Association Between Carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus in Children Gili Regev-Yochay, MD Context Widespread pneumococcal conjugate vaccination may bring about epidemio- Ron Dagan, MD logic changes in upper respiratory tract flora of children. Of particular significance may Meir Raz, MD be an interaction between Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus, in view of the recent emergence of community-acquired methicillin-resistant S aureus. Yehuda Carmeli, MD, MPH Objective To examine the prevalence and risk factors of carriage of S pneumoniae Bracha Shainberg, PhD and S aureus in the prevaccination era in young children. Estela Derazne, MSc Design, Setting, and Patients Cross-sectional surveillance study of nasopharyn- geal carriage of S pneumoniae and nasal carriage of S aureus by 790 children aged 40 Galia Rahav, MD months or younger seen at primary care clinics in central Israel during February 2002. Ethan Rubinstein, MD Main Outcome Measures Carriage rates of S pneumoniae (by serotype) and S aureus; risk factors associated with carriage of each pathogen. TREPTOCOCCUS PNEUMONIAE AND Results Among 790 children screened, 43% carried S pneumoniae and 10% car- Staphylococcus aureus are com- ried S aureus. Staphylococcus aureus carriage among S pneumoniae carriers was 6.5% mon inhabitants of the upper vs 12.9% in S pneumoniae noncarriers. Streptococcus pneumoniae carriage among respiratory tract in children and S aureus carriers was 27.5% vs 44.8% in S aureus noncarriers. Only 2.8% carried both Sare responsible for common infec- pathogens concomitantly vs 4.3% expected dual carriage (P=.03). Risk factors for tions. Carriage of S aureus and S pneu- S pneumoniae carriage (attending day care, having young siblings, and age older than moniae can result in bacterial spread and 3 months) were negatively associated with S aureus carriage. -

Clostridium Difficile Infection: How to Deal with the Problem DH INFORMATION RE ADER B OX

Clostridium difficile infection: How to deal with the problem DH INFORMATION RE ADER B OX Policy Estates HR / Workforce Commissioning Management IM & T Planning / Finance Clinical Social Care / Partnership Working Document Purpose Best Practice Guidance Gateway Reference 9833 Title Clostridium difficile infection: How to deal with the problem Author DH and HPA Publication Date December 2008 Target Audience PCT CEs, NHS Trust CEs, SHA CEs, Care Trust CEs, Medical Directors, Directors of PH, Directors of Nursing, PCT PEC Chairs, NHS Trust Board Chairs, Special HA CEs, Directors of Infection Prevention and Control, Infection Control Teams, Health Protection Units, Chief Pharmacists Circulation List Description This guidance outlines newer evidence and approaches to delivering good infection control and environmental hygiene. It updates the 1994 guidance and takes into account a national framework for clinical governance which did not exist in 1994. Cross Ref N/A Superseded Docs Clostridium difficile Infection Prevention and Management (1994) Action Required CEs to consider with DIPCs and other colleagues Timing N/A Contact Details Healthcare Associated Infection and Antimicrobial Resistance Department of Health Room 528, Wellington House 133-155 Waterloo Road London SE1 8UG For Recipient's Use Front cover image: Clostridium difficile attached to intestinal cells. Reproduced courtesy of Dr Jan Hobot, Cardiff University School of Medicine. Clostridium difficile infection: How to deal with the problem Contents Foreword 1 Scope and purpose 2 Introduction 3 Why did CDI increase? 4 Approach to compiling the guidance 6 What is new in this guidance? 7 Core Guidance Key recommendations 9 Grading of recommendations 11 Summary of healthcare recommendations 12 1. -

Bacillus Cereus Pneumonia

‘Advances in Medicine and Biology’, Volume 67, 2013 Nova Science Publisher Inc., Editor: Berhardt LV To Alessia, my queen, and Giorgia, my princess Chapter BACILLUS CEREUS PNEUMONIA Vincenzo Savini* Clinical Microbiology and Virology, Spirito Santo Hospital, Pescara (PE), Italy ABSTRACT Bacillus cereus is a Gram positive/Gram variable environmental rod, that is emerging as a respiratory pathogen; particularly, pneumonia it causes may be serious and can resemble the anthrax disease. In fact, the organism is strictly related to the famous Bacillus anthracis, with which it shares genotypical, fenotypical, and pathogenic features. Treatment of B. cereus lower airway infections is becoming increasingly hard, due to the spread of multidrug resistance traits among members of the species. Hence, the present chapter’s scope is to shed a light on this bacterium’s lung pathogenicity, by depicting salient microbiological, epidemiological and clinical features it shows. Also, we would like to explore virulence determinants and resistance mechanisms that make B. cereus a life-threatening, potentially difficult-to-treat agent of airway pathologies. * Email: [email protected]. 2 Vincenzo Savini INTRODUCTION The genus Bacillus includes spore-forming species, strains of which are not usually considered to be clinically relevant when isolated from human specimens; in fact, these bacteria are known to be ubiquitously distributed in the environment and may easily contaminate culture material along with improperly handled sample collection devices (Miller, 2012; Brooks, 2001). Bacillus anthracis is the prominent agent of human pathologies within the genus Bacillus, although it is uncommon in most clinical laboratories (Miller, 2012). It is a frank pathogen, as it causes skin and enteric infections; above all, however, it is responsible for a serious lung disease (the ‘anthrax’) that is frequently associated with bloodstream infection and a high mortality rate (Frankard, 2004). -

Lessons from the Anthrax Attacks Implications for US

Lessons from the Anthrax Attacks Implications for US. Bioterrorism Preparedness A Report on a National Forum on Biodefense Author David Heymart Research Assistants Srusha Ac h terb erg, L Joelle Laszld Organized by the Center for Strategic and International Studies and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency --CFr”V? --.....a DlSTRf BUTION This report ISfor official use only; distribution authorized to U S. government agencies, designated contractors, and those with an official need Contains information that may be exempt from public release under the Freedom of Information Act. exemption number 2 (5 USC 552); exemption number 3 (’lo USC 130).Approvalof the Defense Threat Reduction Agency prior to public release is requrred Contract Number OTRAM-02-C-0013 For Official Use Only About CSIS For four decades, the Center for Stravgic and Internahonal Studies (CSIS)has been dedicated 10 providing world leaders with strategic insights on-and pohcy solubons tcurrentand emergtng global lssues CSIS IS led by John J Hamre, former L S deputy secretary of defense It is guided by a board of trustees chaired by former U S senator Sam Nunn and consistlng of prominent individuals horn both the public and private sectors The CSIS staff of 190 researchers and support staff focus pnrnardy on three subjecr areas First, CSIS addresses the fuU spectrum of new challenges to national and mternabonal security Second, it maintains resident experts on all of the world's myor geographical regions Third, it IS committed to helping to develop new methods of governance for the global age, to this end, CSIS has programs on technology and pubhc policy, International trade and finance, and energy Headquartered in Washington, D-C ,CSIS IS pnvate, bipartlsan, and tax-exempt CSIS docs not take specific policy positions, accordygly, all views expressed herein should be understood to be solely those ofthe author Spousor. -

Anthrax Reporting and Investigation Guideline

Anthrax Signs and Symptoms depend on the type of infection; all types can cause severe illness: Symptoms • Cutaneous: painless, pruritic papules or vesicles which form black eschars, often surrounded by edema or erythema. Fever and lymphadenopathy may occur. • Ingestion: Oropharyngeal: mucosal lesion in the oral cavity or oropharynx, sore throat, difficulty swallowing, and swelling of neck. Fever, fatigue, shortness of breath, abdominal pain, nausea/vomiting may occur. Gastrointestinal: abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting/diarrhea, abdominal swelling. Fever, fatigue, and headache are common. • Inhalation: Biphasic, presenting with fever, chills, fatigue, followed by cough, chest pain, shortness of breath, nausea/vomiting, abdominal pain, headache, diaphoresis, and altered mental status. Pleural effusion or mediastinal widening on imaging. • Injection: Severe soft tissue infection; no apparent eschar. Fever, shortness of breath, nausea may occur. Occasional meningeal or abdominal involvement. Incubation Usually < 1 week but as long as 60 days for inhalational anthrax Case Clinical criteria: An illness with at least one specific OR two non-specific symptoms and signs classification that are compatible with one of the above 4 types, systemic involvement, or anthrax meningitis; OR death of unknown cause and consistent organ involvement Confirmed: Clinically Probable: Clinically consistent with Suspect: Clinically consistent with isolation, consistent Gram-positive rods, OR positive consistent with positive IHC, 4-fold rise in test from CLIA-accredited laboratory, OR anthrax test ordered antibodies, PCR, or LF MS epi evidence relating to anthrax but no epi evidence Differential Varies by form; mononucleosis, cat-scratch fever, tularemia, plague, sepsis, bacterial or viral diagnosis pneumonia, mycobacterial infection, influenza, hantavirus Treatment Appropriate antibiotics and supportive care; anthrax antitoxin if spores are activated. -

Bioterrorism, Biological Weapons and Anthrax

Bioterrorism, Biological Weapons and Anthrax Part IV Written by Arthur H. Garrison Criminal Justice Planning Coordinator Delaware Criminal Justice Council Bioterrorism and biological weapons The use of bio-terrorism and bio-warfare dates back to 6th century when the Assyrians poisoned the well water of their enemies. The goal of using biological weapons is to cause massive sickness or death in the intended target. Bioterrorism and biological weapons The U.S. took the threat of biological weapons attack seriously after Gulf War. Anthrax vaccinations of U.S. troops Investigating Iraq and its biological weapons capacity The Soviet Union manufactured various types of biological weapons during the 1980’s • To be used after a nuclear exchange • Manufacturing new biological weapons – Gene engineering – creating new types of viruses/bacteria • Contagious viruses – Ebola, Marburg (Filoviruses) - Hemorrhagic fever diseases (vascular system dissolves) – Smallpox The spread of biological weapons after the fall of the Soviet Union •Material • Knowledge and expertise •Equipment Bioterrorism and biological weapons There are two basic categories of biological warfare agents. Microorganisms • living organic germs, such as anthrax (bacillus anthrax). –Bacteria –Viruses Toxins • By-products of living organisms (natural poisons) such as botulism (botulinum toxin) which is a by- product of growing the microorganism clostridium botulinum Bioterrorism and biological weapons The U.S. was a leader in the early research on biological weapons Research on making -

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA)

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) Over the past several decades, the incidence of resistant gram-positive organisms has risen in the United States. MRSA strains, first identified in the 1960s in England, were first observed in the U.S. in the mid 1980s.1 Resistance quickly developed, increasing from 2.4% in 1979 to 29% in 1991.2 The current prevalence for MRSA in hospitals and other facilities ranges from <10% to 65%. In 1999, MRSA accounted for more than 50% of all Staphylococcus aureus isolates within U.S. intensive care units.3, 4 The past years, however, outbreaks of MRSA have also been seen in the community setting, particularly among preschool-age children, some of whom have attended day-care centers.5, 6, 7 MRSA does not appear to be more virulent than methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, but certainly poses a greater treatment challenge. MRSA also has been associated with higher hospital costs and mortality.8 Within a decade of its development, methicillin resistance to Staphylococcus aureus emerged.9 MRSA strains generally are now resistant to other antimicrobial classes including aminoglycosides, beta-lactams, carbapenems, cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones and macrolides.10,11 Most of the resistance was secondary to production of beta-lactamase enzymes or intrinsic resistance with alterations in penicillin-binding proteins. Staphylococcus aureus is the most frequent cause of nosocomial pneumonia and surgical- wound infections and the second most common cause of nosocomial bloodstream infections.12 Long-term care facilities (LTCFs) have developed rates of MRSA ranging from 25%-35%. MRSA rates may be higher in LTCFs if they are associated with hospitals that have higher rates.13 Transmission of MRSA generally occurs through direct or indirect contact with a reservoir.