Climate Variations, Drought and Desertification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Impact Assessment, Index

SCOPE 27 - Climate Impact Assessment, Index Copyright © 1985 by the Scientific Committee On Problems of the Environment (SCOPE) file:///E|/Web%20Pages/scope/webpage/downloadpubs/scope27/index.html [01/07/2004 10:58:28 p.m.] SCOPE 27 - Climate Impact Assessment, Contents SCOPE 27 Climate Impact Assessment - Studies of the Interaction of Climate and Society Contents Preface List of Contributors PART I OVERVIEWS 1 The Interaction of Climate and Society Robert W. Kates 2 Climatic Variability and Change F. Kenneth Hare 3 Research in Climate-Society Interaction William E. Riebsame 4 Identifying Climate Sensitivity W. J. Maunder and J. H. Ausubel PART II BIOPHYSICAL IMPACTS 5 Agriculture Henry A. Nix 6 Fisheries Tsuyoshi Kawasaki file:///E|/Web%20Pages/scope/webpage/downloadpubs/scope27/contents.html (1 of 3) [01/07/2004 10:58:29 p.m.] SCOPE 27 - Climate Impact Assessment, Contents 7 Pastoralism Henri N. Le Houérou 8 Water Resources Béla Nováky, Csaba Pachner, Károly Szesztay and David Miller 9 Energy Resources Jill Jäger PART III SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC IMPACTS AND ADJUSTMENTS 10 Health, Nutrition, and Human Development José Carlos Escudero 11 Analysis of Historical Climate-Society Interaction Jan de Vries 12 Microeconomic Analysis C. A. Knox Lovell and V. Kerry Smith 13 Social Analysis Barbara Farhar-Pilgrim 14 The Impact of Climatic Variations on Agricultural Margins Martin L. Parry 15 Extreme Event Analysis R. L. Heathcote 16 Perception Anne V. T. Whyte 17 Adjustment in Self-provisioning Societies N. S. Jodha and A. C. Mascarenhas PART IV INTEGRATED ASSESSMENT file:///E|/Web%20Pages/scope/webpage/downloadpubs/scope27/contents.html (2 of 3) [01/07/2004 10:58:29 p.m.] SCOPE 27 - Climate Impact Assessment, Contents 18 Global Modeling and Simulations Jennifer Robinson 19 Biosphere Models N. -

Lniovemlbell' 1985

CONVOlCATiO~ lNIovemlbell' 1985 '-lId L-E M-.};)<fi.• o CANADA 19Ks o CANADA I Our home and native land! (fa 1/) True patriot love in all thy sons command. With glowing hearts we see thee·rise. The True North strong and free! From far and wide. 0 Canada. We stand on guard for thee. God keep our I.md glorious and free! ,.0&' "'-R " ~~nada. we stand on guard for thee . • ,/~~~ ~, ,l • ,\\nada, we stand on guard for thee i~""~ i /~~ ~ , 1 o CANADA t d ~~ " ;/ " "lr. ~." .9 ).'"ANADAI Terre de nos aleux. "\ 04rc""';: "":;'-6n front est ceint de lIeurons glorieux! -. ~._~ ~:a~o~~;: ~!~r:~er I·epee. Ton histoire est une epopee Des plus brillants exploits. Et t.a valeur. de foj ftempt!e. Protegera nos foyers et nos droits Protcgera nos foyers et nos droits. ODE TO NEWFOUNDLAND When sun rays crown thy pi"ne clad hills And Summer spreads her hand When silvern voices tune thy rills, We love thee, smiling land. We love thee. we love thee. We love thee smiling land. As loved our fathers, so we love; Where once they stood. we stand; Their prayer we raise to Heaven above, God guard thee, Newfoundland. God guard thee. God guard thee. God guard thee, Newfoundland. ACADEMIC DRESS The academic dress for matriculated undergraduates of the University shall be similar IOlhe Scholar's Gown of thc University of Oxford. [\ shall be worn whenever the Prnident so directs Hie go"ns of Bachelors shall be nfblack stuff. The go",ns of Ma sleruhal1l:>e nfblack sluff or silk. -

Toward the Establishment of a Disaster Conscious Society

Special Feature Consecutive Disasters --Toward the Establishment of a Disaster Conscious Society-- In 2018, many disasters occurred consecutively in various parts of Japan, including earthquakes, heavy rains, and typhoons. In particular, the earthquake that hit the northern part of Osaka Prefecture on June 18, the Heavy Rain Event of July 2018 centered on West Japan starting June 28, Typhoons Jebi (1821) and Trami (1824), and the earthquake that stroke the eastern Iburi region, Hokkaido Prefecture on September 6 caused damage to a wide area throughout Japan. The damage from the disaster was further extended due to other disaster that occurred subsequently in the same areas. The consecutive occurrence of major disasters highlighted the importance of disaster prevention, disaster mitigation, and building national resilience, which will lead to preparing for natural disasters and protecting people’s lives and assets. In order to continue to maintain and improve Japan’s DRR measures into the future, it is necessary to build a "disaster conscious society" where each member of society has an awareness and a sense of responsibility for protecting their own life. The “Special Feature” of the Reiwa Era’s first White Paper on Disaster Management covers major disasters that occurred during the last year of the Heisei era. Chapter 1, Section 1 gives an overview of those that caused especially extensive damage among a series of major disasters that occurred in 2018, while also looking back at response measures taken by the government. Chapter 1, Section 2 and Chapter 2 discuss the outline of disaster prevention and mitigation measures and national resilience initiatives that the government as a whole will promote over the next years based on the lessons learned from the major disasters in 2018. -

The St·Ructural Evolution Oftyphoo S

NSF/ NOAA ATM 8418204 ATM 8720488 DOD- NAVY- ONR N00014-87-K-0203 THE ST·RUCTURAL EVOLUTION OFTYPHOO S by Candis L. Weatherford SEP 2 6 1989 Pl.-William M. Gray THE STRUCTURAL EVOLUTION OF TYPHOONS By Candis L. Weatherford Department of Atmospheric Science Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO 80523 September, 1989 Atmospheric Science Paper No. 446 ABSTRACT A three phase life cycle characterizing the structural evolution of typhoons has been derived from aircraft reconnaissance data for tropical cyclones in the western North Pacific. More than 750 aircraft reconnaissance missions at 700 mb into 101 northwest Pacific typhoons are examined. The typical life cycle consists of the fol lowing: phase 1) the entire vortex wind field builds as the cyclone attains maximum intensity; phase 2) central pressure fills and maximum winds decrease in association with expanding cyclone size and strengthening of outer core winds; and phase 3) the wind field of the entire vortex decays. Nearly 700 aircraft radar reports of eyewall diameter are used to augment anal yses of the typhoon's life cycle. Eye characteristics and diameter appear to reflect the ease with which the maximum wind field intensifies. On average, an eye first appears with intensifying cyclones at 980 mb central pressure. Cyclones obtaining an eye at pressures higher than 980 mb are observed to intensify more rapidly while those whose eye initially appears at lower pressures deepen at slower rates and typ ically do not achieve as deep a central pressure. The eye generally contracts with intensification and expands as the cyclone fills, although there are frequent excep tions to this rule due to the variable nature of the eyewall size. -

WMO Bulletin, Volume 32, No. 4

- ~ THE WORLD METEOROLOGICAL ORGANIZATION (WMO) is a specialized agency of the Un ited Nations WMO was created: - to faci litate international co-operation in the establishment of networks of stations and centres to provide meteorological and hydrologica l services and observations, 11 - to promote the establishment and maintenance of systems for the rapid exchange of meteoro logical and related information, - to promote standardization of meteorological and related observations and ensure the uniform publication of observations and statistics, - to further the application of meteorology to aviation, shipping, water problems, ag ricu lture and other hu man activities, - to promote activi ties in operational hydrology and to further close co-operation between Meteorological and Hydrological Services, - to encourage research and training in meteorology and, as appropriate, in related fi elds. The World Me!eorological Congress is the supreme body of the Organization. It brings together the delegates of all Members once every four years to determine general policies for the fulfilment of the purposes of the Organization. The ExecuTive Council is composed of 36 directors of national Meteorological or Hydrometeorologica l Services serving in an individual capacity; it meets at least once a year to supervise the programmes approved by Congress. Six Regional AssociaTions are each composed of Members whose task is to co-ordinate meteorological and re lated activities within their respective regions. Eight Tee/mica! Commissions composed of experts designated by Members, are responsible for studying meteorologica l and hydro logica l operational systems, app li ca ti ons and research. EXECUTIVE COUNCIL Preside/11: R. L. KI NTA NA R (Phil ippines) Firs! Vice-Presidenl: Ju. -

Notable Tropical Cyclones and Unusual Areas of Tropical Cyclone Formation

A flood is an overflow of an expanse of water that submerges land.[1] The EU Floods directive defines a flood as a temporary covering by water of land not normally covered by water.[2] In the sense of "flowing water", the word may also be applied to the inflow of the tide. Flooding may result from the volume of water within a body of water, such as a river or lake, which overflows or breaks levees, with the result that some of the water escapes its usual boundaries.[3] While the size of a lake or other body of water will vary with seasonal changes in precipitation and snow melt, it is not a significant flood unless such escapes of water endanger land areas used by man like a village, city or other inhabited area. Floods can also occur in rivers, when flow exceeds the capacity of the river channel, particularly at bends or meanders. Floods often cause damage to homes and businesses if they are placed in natural flood plains of rivers. While flood damage can be virtually eliminated by moving away from rivers and other bodies of water, since time out of mind, people have lived and worked by the water to seek sustenance and capitalize on the gains of cheap and easy travel and commerce by being near water. That humans continue to inhabit areas threatened by flood damage is evidence that the perceived value of living near the water exceeds the cost of repeated periodic flooding. The word "flood" comes from the Old English flod, a word common to Germanic languages (compare German Flut, Dutch vloed from the same root as is seen in flow, float; also compare with Latin fluctus, flumen). -

On Tropical Cyclones

Frequently Asked Questions on Tropical Cyclones Frequently Asked Questions on Tropical Cyclones 1. What is a tropical cyclone? A tropical cyclone (TC) is a rotational low-pressure system in tropics when the central pressure falls by 5 to 6 hPa from the surrounding and maximum sustained wind speed reaches 34 knots (about 62 kmph). It is a vast violent whirl of 150 to 800 km, spiraling around a centre and progressing along the surface of the sea at a rate of 300 to 500 km a day. The word cyclone has been derived from Greek word ‘cyclos’ which means ‘coiling of a snake’. The word cyclone was coined by Heary Piddington who worked as a Rapporteur in Kolkata during British rule. The terms "hurricane" and "typhoon" are region specific names for a strong "tropical cyclone". Tropical cyclones are called “Hurricanes” over the Atlantic Ocean and “Typhoons” over the Pacific Ocean. 2. Why do ‘tropical cyclones' winds rotate counter-clockwise (clockwise) in the Northern (Southern) Hemisphere? The reason is that the earth's rotation sets up an apparent force (called the Coriolis force) that pulls the winds to the right in the Northern Hemisphere (and to the left in the Southern Hemisphere). So, when a low pressure starts to form over north of the equator, the surface winds will flow inward trying to fill in the low and will be deflected to the right and a counter-clockwise rotation will be initiated. The opposite (a deflection to the left and a clockwise rotation) will occur south of the equator. This Coriolis force is too tiny to effect rotation in, for example, water that is going down the drains of sinks and toilets. -

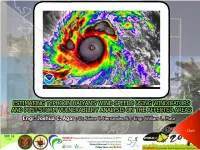

Super Typhoon HAIYAN Crossed the Philippines with High Intensity in November 2013 Dr

Super typhoon HAIYAN crossed the Philippines with high intensity in November 2013 Dr. Susanne Haeseler, Christiana Lefebvre; updated: 13 December 2013 Introduction Super typhoon HAIYAN, on the Philippines known as YOLANDA, crossed the islands between the 7th and 9th November 2013 (Fig. 1 to 3). It is classified as one of the strongest typhoons ever making landfall. The storm surge, triggering widespread floods, and winds of hurricane force caused by HAIYAN wreaked havoc. In this connection, HAIYAN bears much resemblance to a typhoon in the year 1912, even with respect to the effects (see below). Fig. 1: Infrared satellite image of typhoon HAIYAN being located across the Philippines, acquired on 8 November 2013, 09 UTC. Up to 5 m high waves hit the coastal areas. Ships capsized, sank or ran aground. In Tacloban, the capital of the province of Leyte, even three bigger cargo ships were washed on the land. Numerous towns were partly or totally destroyed. Trees were blown down. There were power outages and the communication was knocked out. Destroyed streets and airports hampered the rescue work and further help. Hundreds of thousands of people lost their homes. Although many people sought shelter, thousands lost their lives. 1 The National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC) of the Philippines provided the following information about the effects of the typhoon in the Situational Report No. 61 of 13 December 2013, 6:00 AM, which changed daily even 5 weeks after the event: ▪ 6 009 were reported dead (as of 13 December 2013, 6 AM) ▪ 27 022 injured (as of 13 December 2013, 6 AM) ▪ 1 779 are still missing (as of 13 December 2013, 6 AM) ▪ 3 424 190 families / 16 076 360 persons were affected ▪ out of the total affected, 838 811 families / 3 927 827 persons were displaced and served by evacuation centres ▪ 1 139 731 houses (550 904 totally / 588 827 partially) were damaged. -

Significant Data on Major Disasters Worldwide, 1900-Present

DISASTER HISTORY Signi ficant Data on Major Disasters Worldwide, 1900 - Present Prepared for the Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance Agency for International Developnent Washington, D.C. 20523 Labat-Anderson Incorporated Arlington, Virginia 22201 Under Contract AID/PDC-0000-C-00-8153 INTRODUCTION The OFDA Disaster History provides information on major disasters uhich have occurred around the world since 1900. Informtion is mare complete on events since 1964 - the year the Office of Fore8jn Disaster Assistance was created - and includes details on all disasters to nhich the Office responded with assistance. No records are kept on disasters uhich occurred within the United States and its territories.* All OFDA 'declared' disasters are included - i.e., all those in uhich the Chief of the U.S. Diplmtic Mission in an affected country determined that a disaster exfsted uhich warranted U.S. govermnt response. OFDA is charged with responsibility for coordinating all USG foreign disaster relief. Significant anon-declared' disasters are also included in the History based on the following criteria: o Earthquake and volcano disasters are included if tbe mmber of people killed is at least six, or the total nmber uilled and injured is 25 or more, or at least 1,000 people art affect&, or damage is $1 million or more. o mather disasters except draught (flood, storm, cyclone, typhoon, landslide, heat wave, cold wave, etc.) are included if the drof people killed and injured totals at least 50, or 1,000 or mre are homeless or affected, or damage Is at least S1 mi 1l ion. o Drought disasters are included if the nunber affected is substantial. -

Martin-Lawrence-Friedland-Fonds.Pdf

University of Toronto Archives and Record Management Services Finding Aids – Martin L. Friedland fonds Contains the following accessions: B1998-0006 (pp. 2-149) B2002-0022 (pp. 150-248) B2002-0023 (pp 249-280) B2008-0033 and B2014-0020 (pp. 281-352) To navigate to a particular accession, use the bookmarks in the PDF file University of Toronto Archives Martin L. Friedland Personal Records Finding Aid November 1998 Accession No. B1998–0006 Prepared by Martin L. Friedland With revisions by Harold Averill University of Toronto Archives Accession Number Provenance B1998-0006 Friedland, Martin L. Martin Lawrence Friedland – A biographical sketch Note: Reference should also be made to Friedland’s curriculum vitae and the address on his receiving the Molson Prize in 1995, both of which are appended to the end of the accompanying finding aid. Martin Friedland was born in Toronto in 1932. He was educated at the University of Toronto, in commerce and finance (BCom 1955) and law (LLB 1958), where he was the gold medallist in his graduating year. He continued his academic training at Cambridge University, from which he received his PhD in 1967. Dr. Friedland’s career has embraced several areas where he has utilized his knowledge of commerce and finance as well as of law. He has been a university professor and administrator, a shaper of public policy in Canada through his involvement with provincial and federal commissions, committees and task forces, and is an author of international standing. Dr. Friedland was called to the Ontario Bar in 1960. His contribution to the formation of public policy in Canada began with his earliest research, a study of gambling in Ontario (1961). -

Estimating Typhoon Haiyan's Wind Speeds Using Windicators

Start Year: 2013 Month: November Basin: Northwestern Pacific Areas affected: Visayas Death Toll: 6300+ Amount of Damages: $2.86 Billion ESTIMATES: JTWC : 315 kph (1-min) JMA and PAGASA: 235 kph (10- min) 2 TACLOBAN STATION iCyclone @ TACLOBAN PAGASA - GUIUAN PAGASA - GUIUAN Winds: 230-250 kph 7:20 am – 959.9 mbar 4:10 am – 190 kph 5:10 am – 910 mbar (Hours before Leyte (S 30° W) Time of Closest Approach: 5:15 am landfall) (Aquino, (Severe winds were Time of Landfall at Guiuan – 4:45 Mata, Valdez, 2013) observed from 7:00 am The station was am to 7:50 am) damaged then. 7:00 AM – 277 kph SAN CARLOS, 7:15 am – 955.6 mbar NEGROS BANTAYAN ISLAND OCCIDENTAL MAASIN, SOUTHERN LEYTE Winds: 280 kph (9:45 am)* Winds: 180 kph Winds: 175 kph *Instrument was damaged ROXAS CITY, CAPIZ at this point AJUY, ILOILO Winds: 208.8 kph Closest Approach: 10:30 Winds: 235 kph am 3 October 12-13, 1912 1897 1984 – Typhoon Agnes 1994 – Typhoon Axel 4 5 Wind Speed Estimation Forensic Analysis Satellite Reconnaissance Ground Surface Estimation Missions Measurements Forensic Structural Analysis WINDICATOR •Coined from the terms “Wind” and “Indicator” •Structural objects of interest whose structural failure may lead to the computation of the wind speeds 6 7 Hydraulic UTM MANUAL: ASTM A370-21419 ULTIMATE STRENGTHS: #1 – 473.71 MPa #2 – 389.29 MPa MATERIAL: A36 steel #10 #09 #04 #08 8 LOGARITHMIC WIND PROFILE: EXTERNAL PRESSURE INTERNAL STRESS DISTRIBUTION Harper et.al (2010): Values DISTRIBUTION von Mises stresses for z0 and Csd 9 Harper, B., Kepert, J. -

Mosque Bombers Retract Confessions, Deny Charges

SUBSCRIPTION MONDAY, OCTOBER 26, 2015 MUHARRAM 13, 1437 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Project 189: Assad: Syria Working kids Manchester Reflecting must ‘eradicate given a path rivals draw 0-0 aspirations of terror’ for off Lebanon’s in derby lacking domestic5 helpers political7 deal streets14 attacking20 edge Mosque bombers retract Min 20º confessions, deny charges Max 38º High Tide 10:48 & 22:57 Amir lauds security operations • Speaker hosts MPs, ministers Low Tide 04:37 & 17:05 40 PAGES NO: 16678 150 FILS By B Izzak and Agencies KUWAIT: Suspects in the bombing of the Imam Al- Sadeq Mosque yesterday told the appeals court that they were not guilty and retracted their confessions made in the criminal court, which sentenced seven of them to death. The top suspect, Abdulrahman Sabah, the alleged driver of the bomber, told the appeals court in the first hearing that the confessions they made were extracted from them under torture. Sabah also said that he had not seen the explosives belt although he had told the criminal court that he had brought it from near the Saudi border and given it to the Saudi bomber who blew himself in the mosque, killing 26 people and wounding 227 others. Sabah also KUWAIT: National Assembly Speaker Marzouq Al-Ghanem hosts a traditional dinner banquet for members of parliament and the Cabinet yesterday. — Photo by Yasser Al-Zayyat retracted that he had driven the bomber to the mosque to carry out the suicide attack. The criminal court had sentenced Sabah and six oth- ers to death, five of them in absentia.