The Mastery of Space Daniel Mroz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

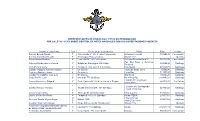

Representantes-22.OCT .14.Pdf

REPRESENTANTES DE DISCIPLINAS Y ESTILOS RECONOCIDOS POR LA LEY Nº 18.356 SOBRE CONTROL DE ARTES MARCIALES CON SUS ACREDITACIONES VIGENTES Nombres y Apellidos Dan Dirección de la academia Estilo Fono Ciudad Alarcón Belmar Oscar 7° Calle Heras N° 813 2° piso Concepción. Defensa Personal 74760436 Concepción Barrera Arancibia Ricardo 8° Aconcagua 752 La Calera. Shaolin Tse Quillota Bruna Urrutia Rodrigo 4° Castellón N° 292 Concepción. Defensa Personal Israelí 56373506 Concepción Pak Mei Kune y Defensa Cabrera Maldonado Hortensia 7° Batalla de Rancagua 539 Maipú. 88550636 Santiago Personal Caro Pizarro Víctor 5° Tarapacá 1324 local 3 A Santiago. Krav Maga 98528875 Santiago Catalán Vásquez Alberto Mauricio 4° En trámite. Taijiquan Estilo Chen 6890530 Santiago Cavieres Martínez Jorge 6° En trámite. Hung Gar 71377097 Santiago Candia Hormazabal José Luis 5° En trámite. Wai Kung 78696520 Santiago Colipí Curiñir Juan 6° Morandé 771 Santiago. Nam Hwa Pai 2-6880123 Santiago Hapkido Cheong Kyum Correa Manríquez Edgard 5° Calle Carrera N° 1624 La Calera V Región. 94171533 La Calera Association. 5° - Choson Mu Sul Hapkido Cubillos Alarcón Richard Vicuña Mackenna N° 227 Santiago. 22472122 Santiago - Pekiti Tirsia Kali 4° Collao Vega Carlos 6° Alameda N° 2489 Santiago Choy Lay Fut 73333201 Santiago Daiber Vuillemín Alberto 4° Tarapacá 777(779) Santiago. Aikikai-FEPAI 29131087 Santiago 9° - Tsung Chiao De Luca Garate Miguel Angel Bilbao 1559 98221052 Santiago 5° - Hung Gar Kuen Escobar Silva Luis Antonio 7° Diego Echeverría N° 786 Quillota. Shaolin Tao Quillota Federación Deportiva Nacional Chilena 6° Libertad N° 86 Santiago. Aikikai 2-6817703 Santiago de Aikido Aikikai (FEDENACHAA) Fernández Soria Mario 5° Castellón N° 292 Concepción. -

Chapter 2 Chinese Martial Arts

Chapter 2 Chinese Martial Arts My adult life has been defined by the practice of traditional Chi- nese body technologies, a long-term practical research project I began on Richard Fowler’s suggestion. From September 1993 to September 2005 I studied cailifoquan (Cantonese: choy li fut kuen), a martial art from Southern China; tang peng taijiquan (Cantonese: tong ping taigek kuen), a Northern Chinese martial art; and zhi neng qigong, a contemporary body technology designed to develop the student’s health and longevity, with Wong Sui Meing in Montréal. Since I started in 1993 I estimate I have completed at least 10,000 hours of training under Wong’s direct supervision. Figure 8: The author’s teacher Wong Sui Meing in his Montréal studio, Wong Kung Fu. (Photo by Daniel Mroz) 46 The Dancing Word In September of 2005 I began to study chen taiji shiyong quanfa, a very old form of taijiquan, under the instruction of Chen Zhonghua. I participated in a series of intensive workshops and private lessons over a two-year period and in May 2007 traveled to Daqingshan Mountain in Shandong Province, China, for a one-month full-time intensive training period. I continue to study privately with Chen as often as his busy international teaching schedule allows. In August 2007 Chen granted me a formal teaching license in the style. In addition to these long-term studies, I have cross-trained in a variety of other styles of martial movement, including Indian kalarip- payattu under the late Govindankutty Nair (d. 2006), Indonesian kun- tao and silat under Willem deThouars and his senior student Randall Goodwin and Chinese baguazhang with Ken Cohen and Allen Pittman. -

Efficacy and Entertainment in Martial Arts Studies D.S. Farrer

Dr. Douglas Farrer is Head of Anthropology at the University CONTRIBUTOR of Guam. He has conducted ethnographic fieldwork in Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Hong Kong, and Guam. D. S. Farrer’s research interests include martial arts, the anthropology of performance, visual anthropology, the anthropology of the ocean, digital anthropology, and the sociology of religion. He authored Shadows of the Prophet: Martial Arts and Sufi Mysticism, and co-edited Martial Arts as Embodied Knowledge: Asian Traditions in a Transnational World. Recently Dr. Farrer compiled ‘War Magic and Warrior Religion: Cross-Cultural Investigations’ for Social Analysis. On Guam he is researching Brazilian jiu-jitsu, scuba diving, and Micronesian anthropology. EFFICACY AND ENTERTAINMENT IN MARTIAL ARTS STUDIES anthropological perspectives D.S. FARRER DOI ABSTRACT 10.18573/j.2015.10017 Martial anthropology offers a nomadological approach to Martial Arts Studies featuring Southern Praying Mantis, Hung Sing Choy Li Fut, Yapese stick dance, Chin Woo, Brazilian jiu-jitsu, and seni silat to address the infinity loop model in the anthropology of performance/performance studies which binds KEYWORDs together efficacy and entertainment, ritual and theatre, social and aesthetic drama, concealment and revelation. The infinity Efficacy, entertainment, loop model assumes a positive feedback loop where efficacy nomadology, Brazilian jiu-jitsu, flows into entertainment and vice versa. The problem addressed seni silat, Chinese martial arts, here is what occurs when efficacy and entertainment collide? performance Misframing, captivation, occulturation, and false connections are related as they emerged in anthropological fieldwork settings CITATION from research into martial arts conducted since 2001, where confounded variables may result in new beliefs in the restoration Farrer, D.S. -

Student Reference Manual

1 Student Reference Manual WHITE TO BLACK BELT CURRICULUM 2 3 UNITED STUDIOS OF SELF DEFENSE Student Reference Manual Copyright © 2019 by United Studios of Self Defense, Inc. All rights reserved. Produced in the United States of America. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any other means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of United Studios of Self Defense, Inc. 3 Table of Contents Student Etiquette 7 Foundation of Kempo 11 USSD Fundamentals 18 USSD Curriculum 21 Technique Index 26 Rank Testing 28 White Belt Curriculum 30 Yellow Belt Curriculum 35 Orange Belt Curriculum 41 Purple Belt Curriculum 49 Blue & Blue/Green Curriculum 55 Green & Green/Brown Curriculum 71 Brown 1st-3rd Stripe Curriculum 83 10 Laws of Kempo 97 Roots of Kempo 103 Our Logo 116 Glossary of Terms 120 4 5 WELCOME TO United Studios of Self Defense As founder and Professor of United Studios of Self Defense, Inc., I would like to personally welcome you to the wonderful world of Martial Arts. Whatever your reason for taking lessons, we encourage you to persevere in meeting your personal goals and needs. You have made the right decision. The first United Studios of Self Defense location was opened on the East Coast in Boston in 1968. Since our founding 50 years ago, we have grown to expand our studio locations nationally from East to West. We are truly North America’s Self Defense Leader and the only organization sanctioned directly by the Shaolin Temple in China to teach the Martial Arts in America. -

Japanese Women, Hong Kong Films, and Transcultural Fandom

SOME OF US ARE LOOKING AT THE STARS: JAPANESE WOMEN, HONG KONG FILMS, AND TRANSCULTURAL FANDOM Lori Hitchcock Morimoto Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Communication and Culture Indiana University April 2011 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee _______________________________________ Prof. Barbara Klinger, Ph.D. _______________________________________ Prof. Gregory Waller, Ph.D. _______________________________________ Prof. Michael Curtin, Ph.D. _______________________________________ Prof. Michiko Suzuki, Ph.D. Date of Oral Examination: April 6, 2011 ii © 2011 Lori Hitchcock Morimoto ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii For Michael, who has had a long “year, two at the most.” iv Acknowledgements Writing is a solitary pursuit, but I have found that it takes a village to make a dissertation. I am indebted to my advisor, Barbara Klinger, for her insightful critique, infinite patience, and unflagging enthusiasm for this project. Gratitude goes to Michael Curtin, who saw promise in my early work and has continued to mentor me through several iterations of his own academic career. Gregory Waller’s interest in my research has been gratifying and encouraging, and I am most appreciative of Michiko Suzuki’s interest, guidance, and insights. Richard Bauman and Sumie Jones were enthusiastic readers of early work leading to this dissertation, and I am grateful for their comments and critique along the way. I would also like to thank Joan Hawkins for her enduring support during her tenure as Director of Graduate Studies in CMCL and beyond, as well as for the insights of her dissertation support group. -

Strategic Representations of Chinese Cultural Elements in Maxine Hong Kingston's and Amy Tan's Works

School of Media, Culture and Creative Arts When Tiger Mothers Meet Sugar Sisters: Strategic Representations of Chinese Cultural Elements in Maxine Hong Kingston's and Amy Tan's Works Sheng Huang This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Curtin University December 2017 Declaration To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgment has been made. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. Signature: …………………………………………. Date: ………………………... i Abstract This thesis examines how two successful Chinese American writers, Maxine Hong Kingston and Amy Tan, use Chinese cultural elements as a strategy to challenge stereotypes of Chinese Americans in the United States. Chinese cultural elements can include institutions, language, religion, arts and literature, martial arts, cuisine, stock characters, and so on, and are seen to reflect the national identity and spirit of China. The thesis begins with a brief critical review of the Chinese elements used in Kingston’s and Tan’s works, followed by an analysis of how they created their distinctive own genre informed by Chinese literary traditions. The central chapters of the thesis elaborate on how three Chinese elements used in their works go on to interact with American mainstream culture: the character of the woman warrior, Fa Mu Lan, who became the inspiration for the popular Disney movie; the archetype of the Tiger Mother, since taken up in Amy Chua’s successful book Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother; and Chinese style sisterhood which, I argue, is very different from the ‘sugar sisterhood’ sometimes attributed to Tan’s work. -

Cai Li Fo from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia (Redirected from Choy Lee Fut)

Cai Li Fo From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Choy Lee Fut) Cai Li Fo (Mandarin) or Choy Li Fut (Cantonese) (Chinese: 蔡李佛; pinyin: Cài L! Fó; Cantonese Yale: Choi3 Lei5 Fat6; Cai Li Fo aka Choy Lee Fut Kung Fu) is a Chinese martial art founded in Chinese 蔡李佛 [1] 1836 by Chan Heung (陳享). Choy Li Fut was named to Transcriptions honor the Buddhist monk Choy Fook (蔡褔, Cai Fu) who taught him Choy Gar, and Li Yau-San (李友山) who taught Mandarin him Li Gar, plus his uncle Chan Yuen-Wu (陳遠護), who - Hanyu Pinyin Cài L! Fó taught him Fut Gar, and developed to honor the Buddha and - Wade–Giles Ts'ai4 Li3 Fo2 the Shaolin roots of the system.[2] - Gwoyeu Romatzyh Tsay Lii For The system combines the martial arts techniques from various Cantonese (Yue) [3] Northern and Southern Chinese kung-fu systems; the - Jyutping Coi3 Lei5 Fat6 powerful arm and hand techniques from the Shaolin animal - Yale Romanization Kai Li Fwo forms[4] from the South, combined with the extended, circular movements, twisting body, and agile footwork that characterizes Northern China's martial arts. It is considered an Part of the series on external style, combining soft and hard techniques, as well as Chinese martial arts incorporating a wide range of weapons as part of its curriculum.[5] Choy Li Fut is an effective self-defense system,[6] particularly noted for defense against multiple attackers.[7] It contains a wide variety of techniques, including long and short range punches, kicks, sweeps and take downs, pressure point attacks, joint locks, and grappling.[8] According to Bruce Lee:[9] "Choy Li Fut is the most effective system that I've seen for fighting more than one person. -

Forget About the Men, It's Time for the Ladies to Step Into the Spotlight

Forget about the men, it’s time for the ladies to step into the spotlight. Arthur Tam explores the women that have shaped, contributed and kicked major ass in Hong Kong martial arts cinema. Photography by Calvin Sit. Art Direction by Phoebe Cheng. Cover art by Stanley Chung timeout.com.hk 19 o one would argue that Hong Kong, starting with the rise of since much of the genre was shaped by female fighters like Cheng Pei- Shaw Brothers, has dominated martial arts cinema for much pei, Kara Hui, Michelle Yeoh, Angela Mao, Cynthia Rothrock and Yuen Cheng Pei-pei of the last 50 years. Local film makers laid the foundation Qiu. In the 50s and 60s, female lead roles in wuxia and kung fu films 鄭佩佩 for many of the greatest action films ever made, giving rise were just as prevalent as male roles and the ladies threw it down with Nto revered international action heroes like Jet Li, Donnie Yen, Jackie as much strength, speed and tenacity as the men did, if not more. The queen of swords Chan and, of course, the greatest of the greatest, the dragon himself, These day it’s all about fighting to level the playing field and in the Bruce Lee. light of increasing girl power, what better way to celebrate than to Yes, these are the men that we adore to this day, but we forget acknowledge women in an industry that has been so essential to the ’m always up for a fight,” says 70-year- that to their yang there has always been a strong yin.The great popularity of Hong Kong pop culture. -

Red Belt Study Sheet

Starkville TaeKwonDo RED BELT STUDY SHEET TERMINOLOGY: Know all terminology from white belt to red belt COMBINATIONS: Candidates will demonstrate techniques in sets of (4), using pattern administered by the test board. Example: block-attack- block-attack FACTS: Know all from white belt to now PROMINENT NAMES: Know and be able to elaborate on (5) prominent names in martial arts PROMINENT STYLES: Know and be able to elaborate on (5) prominent styles of martial arts SELF-DEFENSE: Perform required self-defense that was learned at white belt Present (8) pre-determined close quarter self-defense techniques Be able to extricate yourself from holds administered by the test board QUESTIONS: Answer any and all questions posed by the test board FORMS/HYUNG: Perform and recite meanings of all forms from Chon-Ji through Hwa-Rang Be able to recognize any (3) movements from the form Hwa-Rang and Chung-Mu. Movements will be performed by members of test board. • Chon-Ji --- (19 movements, 2 kihaps) - Heaven and Earth • Tan-Gun --- (21 movements, 3 kihaps) - The legendary founder of Korea in 2333 B.C. • To San --- (24 movements, 3 kihaps) - Named after Master Ahn Chung Ho, a great patriot and educator of Korea. • Won-Hyo --- (28 movements, 3 kihaps) - named for the monk who introduced Buddhism to the Silla Dynasty in 686 A.D. • Yul-Kok --- (38 movements, 3 kihaps) - known as the “Confucius of Korea.” The 38 movements of this pattern represent the 38th degree latitude of his birthplace. The diagram of this pattern represents scholar. • Chung-Gun --- (32 movements, 3 kihaps) - named after master Ahn Chung Gun who assassinated the first Japanese overlord of Korea. -

Download Issue

ISSUE 10 EDITORS Fall 2020 Paul Bowman ISSN 2057-5696 Benjamin N. Judkins MARTIAL ARTS STUDIES EDITORIAL PAUL BOWMAN & BENJAMIN N. JUDKINS Five Years and Twelve Months that Changed the Study of Martial Arts Forever ABOUT THE JOURNAL Martial Arts Studies is an open access journal, which means that all content is available without charge to the user or his/her institution. You are allowed to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of the articles in this journal without asking prior permission from either the publisher or the author. The journal is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Original copyright remains with the contributing author and a citation should be made when the article is quoted, used or referred to in another work. C b n d Martial Arts Studies is an imprint of Cardiff University Press, an innovative open-access publisher of academic research, where ‘open-access’ means free for both readers and writers. cardiffuniversitypress.org Journal DOI 10.18573/ISSN.2057-5696 Issue DOI 10.18573/mas.i10 Accepted for publication 30 October 2020 Martial Arts Studies Journal design by Hugh Griffiths MARTIAL issue 10 ARTS STUDIES FALL 2020 1 Editorial Five Years and Twelve Months that Changed the Study of Martial Arts Forever Paul Bowman and Benjamin N. Judkins ARTICLES 9 Tàolù – The Mastery of Space Daniel Mroz 23 Marx, Myth and Metaphysics China Debates the Essence of Taijiquan Douglas Wile 40 Rural Wandering Martial Arts Networks and Invulnerability Rituals in Modern China Yupeng Jiao 51 The Construction of Chinese Martial Arts in the Writings of John Dudgeon, Herbert Giles and Joseph Needham Tommaso Gianni 66 The Golden Square Dojo and its Place in British Jujutsu History David Brough 73 Wrestling, Warships and Nationalism in Japanese-American Relations Martin J. -

Petit Guide Des Pratiques Martiales

Petit guide des pratiques martiales. Antoine Thibaut Avant propos Les pratiques martiales qu’il s’agisse d’arts martiaux, de sports de combats ou de méthodes de self défense sont un élément important de l’histoire de l’humanité. Au même titre que des choses comme la musique, la cuisine, la peinture… ils sont le fruit de sociétés et d’époques et ont évolué au fil du temps. Or, si aujourd’hui en parlant de pratiques martiales on se limite souvent aux simples arts martiaux du Japon, de la Chine de la Corée et de l'Europe de l’ouest voire de l'Asie du sud est, on trouve des pratiques martiales sur tous les continents et beaucoup d’entre elles sont méconnues. Le présent livret a pour but de vous amener à la découverte de manière très succincte d’un certain nombre de pratiques plus ou moins connues. Loin d’être exhaustif, il cherche simplement à être un point de départ pour attiser votre curiosité concernant le monde très vaste et riche des pratiques martiales. De pratiques connues comme le judo japonais à d’autres bien plus confidentielles comme le donga éthiopien, vous devriez découvrir un monde plus vaste que celui que vous imaginiez. Créé à l’occasion des 6 ans de « L’Art de la voie » il sera disponible gratuitement en téléchargement sur le site et mis à jour régulièrement. 2 Aïkido Origines: Lieu: Japon Date: 1930-1960 Fondateur: Moriheï Ueshiba (1877-1969) Bref historique : Si l’aïkido est d’origine récente (XXème siècle) ses racines sont très anciennes. -

Struktura Stylů V Kung-Fu“ a Pokusím Se Rozdělit Jednotlivé Styly Čínského Bojového Umění Kung-Fu

ÚVOD Ve své bakalářské práci se budu zabývat problematikou na téma „Struktura stylů v kung-fu“ a pokusím se rozdělit jednotlivé styly čínského bojového umění kung-fu . Co mě k tomu vedlo? Byl to především nedostatek informací o obsáhlejším, systematickém a současně jasném rozdělení, pokud možno co největšího počtu stylů čínského kung-fu , v česky psané literatuře. Dalším důvodem je skutečnost, že již několik let toto bojové umění praktikuji, a přestože mne tato problematika zajímá a rád bych se v ní orientoval, neustále se mi těchto informací nedostává. Zároveň vím, že existuje mnoho lidí, kteří by si rádi udělali představu o tom, jak jednotlivé styly zařadit. A právě těm by přečtení mé práce mohlo obzvlášť pomoci. Na našem trhu existuje množství publikací. Některé jsou úzce specializované na jeden styl, jiné jsou zase příliš všeobecné, zaobírající se nejrůznějšími bojovými systémy světa bez jejich hlubšího zkoumání. Ale nesetkal jsem se s takovou literaturou, která by obsahovala ucelený přehled stylů a jejich zařazení v rámci systému bojového umění kung-fu. Navíc se různí autoři, popisující stejné styly, dost často názorově rozchází. Předpokládám, že z těchto důvodů se mi všechny styly zařadit nepodaří. K tomu, aby bylo možno jednotlivé styly v rámci čínského bojového umění kung-fu strukturovat, je nutno si utvořit představu o historii boje lidstva všeobecně, abychom viděli kung-fu v širších souvislostech, ne pouze jako izolovaný systém. Dále je nutné znát historii samotného bojového umění kung-fu kvůli pochopení hlubších souvislostí nejen mezi jednotlivými styly, ale také o jejich provázanosti s kulturou, geografickou polohou atd., které hrají důležitou roli při rozdělení stylů.