Efficacy and Entertainment in Martial Arts Studies D.S. Farrer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tai Chi Sword DR

TAI CHI CHUAN / MARTIAL ARTS B2856 BESTSELLING AUTHOR OF BOOKS AND VIDEOS ON TAI CHI, MARTIAL ARTS, AND QIGONG Tai Chi Sword Chi Sword Tai DR. YANG, JWING-MING REACH FOR THE HIGHEST LEVEL OF TAI CHI PRACTICE You can achieve the highest level of tai chi practice by including tai chi sword in your training regimen. Here’s your chance to take the next step in your tai chi journey Once you have attained proficiency in the bare-hand form, and have gained listening and sensing skills from pushing hands, you are ready for tai chi sword. Tai Chi Sword The elegant and effective techniques of traditional tai chi sword CLASSICAL YANG STYLE Tai chi sword will help you control your qi, refine your tai chi skills, and master yourself. You will strengthen and relax your body, calm and focus your mind, THE COMPLETE FORM, QIGONG, AND APPLICATIONS improve your balance, and develop proper tai chi breathing. This book provides a solid and practical approach to learning tai chi sword Style Classical Yang One of the people who have “made the accurately and quickly. Includes over 500 photographs with motion arrows! greatest impact on martial arts in the • Historical overview of tai chi sword past 100 years.” • Fundamentals including hand forms and footwork —Inside Kung Fu • Generating power with the sword 傳 Magazine • 12 tai chi sword breathing exercises • 30 key tai chi sword techniques with applications • 12 fundamental tai chi sword solo drills 統 • Complete 54-movement Yang Tai Chi Sword sequence • 48 martial applications from the tai chi sword sequence DR. -

Journal of Combat Sports Medicine

Association of Ringside Physicians Journal of Combat Sports Medicine Volume 2, Issue 2 July 2020 Journal of Combat Sports Medicine | Editor-in-Chief, Editorial Board Nitin K. Sethi, MD, MBBS, FAAN, is a board certified neurologist with interests in Clinical Neurology, Epilepsy and Sleep Medicine. After completing his medical school from Maulana Azad Medical College (MAMC), University of Delhi, he did his residency in Internal Medicine (Diplomate of National Board, Internal Medicine) in India. He completed his neurology residency from Saint Vincent’s Medical Center, New York and fellowship in epilepsy and clinical neurophysiology from Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York. Dr. Sethi is a Diplomate of the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN), Diplomate of American Board of Clinical Neurophysiology (ABCN) with added competency in Central Clinical Neurophysiology, Epilepsy Monitor- ing and Intraoperative Monitoring, Diplomate of American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN) with added competency in Epilepsy, Diplomate of American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN) with added competency in Sleep Medicine and also a Diplomate American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM)/Association of Ringside Physicians (ARP) and a Certified Ringside Physician. He is a fellow of the American Academy of Neurology (FAAN) and serves on the Board of the Associa- tion of Ringside Physicians. He currently serves as Associate Professor of Neurology, New York-Presbyterian Hospital, Weill Cornell Medical Center and Chief Medical Officer of the New York State Athletic Commission. | Journal of Combat Sports Medicine Editorial Staff Susan Rees, Senior Managing Editor Email: [email protected] Susan Rees, The Rees Group President and CEO, has over 30 years of association experience. -

The Safety of BKB in a Modern Age

The Safety of BKB in a modern age Stu Armstrong 1 | Page The Safety of Bare Knuckle Boxing in a modern age Copyright Stu Armstrong 2015© www.stuarmstrong.com Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 3 The Author .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Why write this paper? ......................................................................................................................... 3 The Safety of BKB in a modern age ................................................................................................... 3 Pugilistic Dementia ............................................................................................................................. 4 The Marquis of Queensbury Rules’ (1867) ......................................................................................... 4 The London Prize Ring Rules (1743) ................................................................................................. 5 Summary ............................................................................................................................................. 7 Bibliography ........................................................................................................................................ 8 2 | Page The Safety of Bare Knuckle Boxing in a modern age Copyright Stu Armstrong 2015© -

2016 /2017 NFHS Wrestling Rules

2016 /2017 NFHS wrestling Rules The OHSAA and the OWOA wish to thank the National Federation of State High School Associations for the permission to use the photographs to illustrate and better visually explain situations shown in the back of the 2016/17 rule book. © Copyright 2016 by OHSAA and OWOA Falls And Nearfalls—Inbounds—Starting Positions— Technical Violations—Illegal Holds—Potentially Dangerous (5-11-2) A fall or nearfall is scored when (5-11-2) A near fall may be scored when the any part of both scapula are inbounds and the defensive wrestler is held in a high bridge shoulders are over or outside the boundary or on both elbows. line. Hand over nose and mouth that restricts breathing (5-11-2) A near fall may be scored when the (5-14-2) When the defensive wrestler in a wrestler is held in a high bridge or on both pinning situation, illegally puts pressure over elbows the opponents’s mouth, nose, or neck, it shall be penalized. Hand over nose and mouth Out-of-bounds that restricts Inbounds breathing Out-of-bounds Out-of-bounds Inbounds (5-15-1) Contestants are considered to be (5-14-2) Any hold/maneuver over the inbounds if the supporting points of either opponent’s mouth, nose throat or neck which wrestler are inside or on but not beyond the restricts breathing or circulation is illegal boundary 2 Starting Position Legal Neutral Starting Position (5-19-4) Both wrestlers must have one foot on the Legal green or red area of the starting lines and the other foot on line extended, or behind the foot on the line. -

Hand to Hand Combat

*FM 21-150 i FM 21-150 ii FM 21-150 iii FM 21-150 Preface This field manual contains information and guidance pertaining to rifle-bayonet fighting and hand-to-hand combat. The hand-to-hand combat portion of this manual is divided into basic and advanced training. The techniques are applied as intuitive patterns of natural movement but are initially studied according to range. Therefore, the basic principles for fighting in each range are discussed. However, for ease of learning they are studied in reverse order as they would be encountered in a combat engagement. This manual serves as a guide for instructors, trainers, and soldiers in the art of instinctive rifle-bayonet fighting. The proponent for this publication is the United States Army Infantry School. Comments and recommendations must be submitted on DA Form 2028 (Recommended Changes to Publications and Blank Forms) directly to Commandant, United States Army Infantry School, ATTN: ATSH-RB, Fort Benning, GA, 31905-5430. Unless this publication states otherwise, masculine nouns and pronouns do not refer exclusively to men. iv CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Hand-to-hand combat is an engagement between two or more persons in an empty-handed struggle or with handheld weapons such as knives, sticks, and rifles with bayonets. These fighting arts are essential military skills. Projectile weapons may be lost or broken, or they may fail to fire. When friendly and enemy forces become so intermingled that firearms and grenades are not practical, hand-to-hand combat skills become vital assets. 1-1. PURPOSE OF COMBATIVES TRAINING Today’s battlefield scenarios may require silent elimination of the enemy. -

Aboutdog Brothersmartial Arts

About Dog Brothers Martial Arts Dog Brothers Martial Arts (DBMA) is a system of many styles where the ultimate goal is to “walk as a warrior for all your days™.” As such we have an ap- proach that is in search of the totality of both ritual combat (sport fighting such as Mixed Martial Arts/Vale Tudo, Muay Kickboxing, Brazilian Jiu Jitsu and others) and reality (practical street defense, weapon awareness, and uneven odds). This means that the greater mission is to have real skills throughout the entirety of one’s life—not just when one is young and competitive. Considerable thought and experience has gone into the development of this cur- riculum, and as is the case with all things taught in the DBMA curriculum: “If you see it taught, you see it fought.™” The curriculum is divided into 3 areas: Real Contact Stick Fighting, Kali Tudo™ and Die Less Often. A brief overview of these areas of study is found on the next page. What You’ll Learn Consistency Across Categories Fun, Fit, and Functional Hurting, Healing, and Harmonizing The Filipino Martial Arts are unique in that they As previously stated, we look to share the long In addition to combative tools, tactics, and focus on weapons first, and allow the learning that term training goal: “walk as a warrior for all techniques, DBMA also incorporates a healing takes place there to inform a practitioner’s empty your days™” with you. For the long term, it of component to training. We include yoga, alignment hand movements and skills. -

Intracultural and Intercultural Dynamics of Capoeira Training in Brazil Paul H

ge Intracultural and Intercultural Dynamics of Capoeira Training in Brazil Paul H. Mason Journal ǁ Global Ethnographic Publication Date ǁ 1.2013 ǁ No.1 ǁ Publisher ǁ Emic Press Global Ethnographic is an open access journal. Place of Publication ǁ Kyoto, Japan ISSN 2186-0750 © Copyright Global Ethnographic 2013 Global Ethnographic and Emic Press are initiatives of the Organization for Intra-Cultural Development (OICD). Global Ethnographic 2012 photograph by Puneet Singh (2009) 2 Paul H. Mason ge Capoeira Angola performance outside the Santo Antônio Além do Carmo, also known as the Forte da Capoeira, in Salvador da Bahia, Brazil. 3 Intracultural and Intercultural Dynamics of Capoeira Training in Brazil Paul H. Mason ABSTRACT In the port-cities of Brazil during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, a distinct form of combat- dancing emerged from the interaction of African, European and indigenous peoples. The acrobatic movements and characteristic music of this art have come to be called Capoeira. Today, the art of Capoeira has grown in popularity and groups of practitioners can be found scattered across the globe. Exploring how Capoeira practitioners invent markers of difference between separate groups, the first section of this article discusses musical markers of identity that reinforce in-group and out- group dynamics. At a separate but interconnected level of analysis, the second section investigates the global origins of Capoeira movement and disambiguates the commonly recounted origin myths promoted by teachers and scholars of this art. Practitioners frequently relate stories promoting the African origins of Capoeira. However, these stories obfuscate the global origins of Capoeira music and movement and conceal the various contributions to this vibrant and eclectic form of cultural ex- pression. -

Congratulations to Wudang San Feng Pai!

LIFE / HEALTH & FITNESS / FITNESS & EXERCISE Congratulations to Wudang San Feng Pai! February 11, 2013 8:35 PM MST View all 5 photos Master Zhou Xuan Yun (left) presented Dr. Ming Poon (right) Wudang San Feng Pai related material for a permanent display at the Library of Congress. Zhou Xuan Yun On Feb. 1, 2013, the Library of Congress of the United States hosted an event to receive Wudang San Feng Pai. This event included a speech by Taoist (Daoist) priest and Wudang San Feng Pai Master Zhou Xuan Yun and the presentation of important Wudang historical documents and artifacts for a permanent display at the Library. Wudang Wellness Re-established in recent decades, Wudang San Feng Pai is an organization in China, which researches, preserves, teaches and promotes Wudang Kung Fu, which was said originally created by the 13th century Taoist Monk Zhang San Feng. Some believe that Zhang San Feng created Tai Chi (Taiji) Chuan (boxing) by observing the fight between a crane and a snake. Zhang was a hermit and lived in the Wudang Mountains to develop his profound philosophy on Taoism (Daoism), internal martial arts and internal alchemy. The Wudang Mountains are the mecca of Taoism and its temples are protected as one of 730 registered World Heritage sites of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Wudang Kung Fu encompasses a wide range of bare-hand forms of Tai Chi, Xingyi and Bagua as well as weapon forms for health and self-defense purposes. Traditionally, it was taught to Taoist priests only. It was prohibited to practice during the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966- 1976). -

Dancing Through Difficulties: Capoeira As a Fight Against Oppression by Sara Da Conceição

Dancing Through Difficulties: Capoeira as a Fight Against Oppression by Sara da Conceição Capoeira is difficult to define. It is an African form of physical, spiritual, and cultural expression. It is an Afro-Brazilian martial art. It is a dance, a fight, a game, an art form, a mentality, an identity, a sport, an African ritual, a worldview, a weapon, and a way of life, among other things. Sometimes it is all of these things at once, sometimes it isn’t. It can be just a few of them or something different altogether. Capoeira is considered a “game” not a “fight” or a “match,” and the participants “play” rather than “fight” against each other. There are no winners or losers. It is dynamic and fluid: there is no true beginning or end to the game of capoeira. In perhaps the most widely recognized and referenced book dealing with capoeira, Ring of Liberation: Deceptive Discourse in Brazilian Capoeira, J. Lowell Lewis attempts to orient the reader with a fact-based, straightforward description of this blurred cultural genre: A game or sport played throughout Brazil (and elsewhere in the world) today, which was originally part of the Afro-Brazilian folk tradition. It is a martial art, involving a complete system of self-defense, but it also has a dance-like, acrobatic movement style which, combined with the presence of music and song, makes the games into a kind of performance that attracts many kinds of spectators, both tourists and locals. (xxiii) An outsider experiencing capoeira for the first time would undoubtedly assert that the “game” is a spectacular, impressive, and peculiar sight, due to its graceful and spontaneous integration of fighting techniques with dance, music, and unorthodox acrobatic movements. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 278 2nd Yogyakarta International Seminar on Health, Physical Education, and Sport Science (YISHPESS 2018) 1st Conference on Interdisciplinary Approach in Sports (CoIS 2018) Martial art of Dayak Central Kalimantan (a Study of History, Philosophy, and Techniques of Traditional Martial Arts) Eko Hernando Siswantoyo Graduated Program Graduated Program Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta Yogyakarta, Indonesia Yogyakarta, Indonesia [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—This study aims to explore how the history of baboon called as Southern pig-tailed which is called macaca traditional Dayak martial arts in Central Kalimantan, the nemestrina in Latin. philosophy contained therein, and the techniques of martial The bangkui stance is the main or ultimate technique to arts in Dayak Central Kalimantan. The research applied a turn off and lock the opponent's movements because, the qualitative research with historical research method. The Data bangkui movement itself has a some techniques capable of sources in the study were obtained through three traditional paralyzing an opponent with just an attack. This traditional martial arts colleges in Central Kalimantan, namely; martial art tends to use bare hands and relys on the agility of Pangunraun Pitu (East Barito regency), Silat Sakti Salamat the players' movements, although there are also some martial Kambe (Katingan regency), and Palampang Panerus Tinjek art practitioners who use weapons. This pattern of the (Pulang Pisau regency). The data collection techniques used traditional self-defense tends to attack enemies from the were observation, interviews, and documentation. The results showed that (1) the figure who first spread the martial arts of bottom and directly attacks the opponent's body's defensive the Dayak tribe into all parts of Central Kalimantan were two points. -

Representantes-22.OCT .14.Pdf

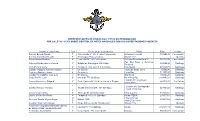

REPRESENTANTES DE DISCIPLINAS Y ESTILOS RECONOCIDOS POR LA LEY Nº 18.356 SOBRE CONTROL DE ARTES MARCIALES CON SUS ACREDITACIONES VIGENTES Nombres y Apellidos Dan Dirección de la academia Estilo Fono Ciudad Alarcón Belmar Oscar 7° Calle Heras N° 813 2° piso Concepción. Defensa Personal 74760436 Concepción Barrera Arancibia Ricardo 8° Aconcagua 752 La Calera. Shaolin Tse Quillota Bruna Urrutia Rodrigo 4° Castellón N° 292 Concepción. Defensa Personal Israelí 56373506 Concepción Pak Mei Kune y Defensa Cabrera Maldonado Hortensia 7° Batalla de Rancagua 539 Maipú. 88550636 Santiago Personal Caro Pizarro Víctor 5° Tarapacá 1324 local 3 A Santiago. Krav Maga 98528875 Santiago Catalán Vásquez Alberto Mauricio 4° En trámite. Taijiquan Estilo Chen 6890530 Santiago Cavieres Martínez Jorge 6° En trámite. Hung Gar 71377097 Santiago Candia Hormazabal José Luis 5° En trámite. Wai Kung 78696520 Santiago Colipí Curiñir Juan 6° Morandé 771 Santiago. Nam Hwa Pai 2-6880123 Santiago Hapkido Cheong Kyum Correa Manríquez Edgard 5° Calle Carrera N° 1624 La Calera V Región. 94171533 La Calera Association. 5° - Choson Mu Sul Hapkido Cubillos Alarcón Richard Vicuña Mackenna N° 227 Santiago. 22472122 Santiago - Pekiti Tirsia Kali 4° Collao Vega Carlos 6° Alameda N° 2489 Santiago Choy Lay Fut 73333201 Santiago Daiber Vuillemín Alberto 4° Tarapacá 777(779) Santiago. Aikikai-FEPAI 29131087 Santiago 9° - Tsung Chiao De Luca Garate Miguel Angel Bilbao 1559 98221052 Santiago 5° - Hung Gar Kuen Escobar Silva Luis Antonio 7° Diego Echeverría N° 786 Quillota. Shaolin Tao Quillota Federación Deportiva Nacional Chilena 6° Libertad N° 86 Santiago. Aikikai 2-6817703 Santiago de Aikido Aikikai (FEDENACHAA) Fernández Soria Mario 5° Castellón N° 292 Concepción. -

Inertial Sensors for Performance Analysis in Combat Sports: a Systematic Review

sports Article Inertial Sensors for Performance Analysis in Combat Sports: A Systematic Review Matthew TO Worsey , Hugo G Espinosa * , Jonathan B Shepherd and David V Thiel School of Engineering and Built Environment, Griffith University, Brisbane, QLD 4111, Australia; matthew.worsey@griffithuni.edu.au (M.T.O.W.); j.shepherd@griffith.edu.au (J.B.S.); d.thiel@griffith.edu.au (D.V.T.) * Correspondence: h.espinosa@griffith.edu.au; Tel.: +61-7-3735-8432 Received: 5 December 2018; Accepted: 18 January 2019; Published: 21 January 2019 Abstract: The integration of technology into training and competition sport settings is becoming more commonplace. Inertial sensors are one technology being used for performance monitoring. Within combat sports, there is an emerging trend to use this type of technology; however, the use and selection of this technology for combat sports has not been reviewed. To address this gap, a systematic literature review for combat sport athlete performance analysis was conducted. A total of 36 records were included for review, demonstrating that inertial measurements were predominately used for measuring strike quality. The methodology for both selecting and implementing technology appeared ad-hoc, with no guidelines for appropriately analysing the results. This review summarises a framework of best practice for selecting and implementing inertial sensor technology for evaluating combat sport performance. It is envisaged that this review will act as a guide for future research into applying technology to combat sport. Keywords: combat sport; technology; inertial sensor; performance 1. Introduction In recent years, technological developments have resulted in the production of small, unobtrusive wearable inertial sensors.