Trends and Developments in Interreligious Dialogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

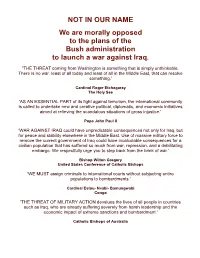

NOT in OUR NAME We Are Morally Opposed to the Plans of the Bush Administration to Launch a War Against Iraq

NOT IN OUR NAME We are morally opposed to the plans of the Bush administration to launch a war against Iraq. 'THE THREAT coming from Washington is something that is simply unthinkable. There is no war, least of all today and least of all in the Middle East, that can resolve something.' Cardinal Roger Etchegaray The Holy See 'AS AN ESSENTIAL PART of its fight against terrorism, the international community is called to undertake new and creative political, diplomatic, and economic initiatives aimed at relieving the scandalous situations of gross injustice.' Pope John Paul II 'WAR AGAINST IRAQ could have unpredictable consequences not only for Iraq, but for peace and stability elsewhere in the Middle East. Use of massive military force to remove the current government of Iraq could have incalculable consequences for a civilian population that has suffered so much from war, repression, and a debilitating embargo. We respectfully urge you to step back from the brink of war.' Bishop Wilton Gregory United States Conference of Catholic Bishops 'WE MUST assign criminals to international courts without subjecting entire populations to bombardments.' Cardinal Estou- Nvabi- Bamungwabi Congo 'THE THREAT OF MILITARY ACTION devalues the lives of all people in countries such as Iraq, who are already suffering severely from harsh leadership and the economic impact of extreme sanctions and bombardment.' Catholic Bishops of Australia No war in our name. The Benedictine Monks of Weston Priory Fall/Winter 2002 Bulletin The Monks of Weston Priory 58 Priory Hill Road, Weston, VT 05161-6400 Tel: 802-824-5409; Fax: 802-824-3573 . -

Liturgy 40 Years After the Council the Oneness of the Church

Aug. 27–Sept.America 3, 2007 THE NATIONAL CATHOLIC WEEKLY $2.75 The Oneness of Liturgy 40 the Church Years After Richard the Council Gaillardetz Godfried Danneels Richard A. Blake on Ingmar Bergman as a religious thinker Willard F. Jabusch on Franz Jägerstätter NE SUMMER in Maryland I vol- would offer, to craft and enforce laws that unteered to teach in a local further the common good of all Ameri- America Head Start program, but what I cans. Humphrey fit the bill. What I Published by Jesuits of the United States needed instead was a paying didn’t expect was to be inspired by co- Ojob. So when my roommate dashed home workers. Editor in Chief with the news that the Democratic Yet I saw about me men and women Drew Christiansen, S.J. National Committee was hiring over at of varying ages, types and career levels the Watergate building, we rushed back who embodied another democratic ideal: Managing Editor to the District to apply and interview. the politically active citizen as party Robert C. Collins, S.J. That night we landed jobs in the press worker. These people toiled behind the office. It was 1968, a few months before scenes and within the system. Their hard Business Manager Election Day. And the Hubert Humphrey work, enthusiasm and dedication moved Lisa Pope versus Richard Nixon presidential race me; all of us worked nearly around the was entering its final critical leg. clock as the weeks sped by. And while Editorial Director This is the story of how a college senior staff members were surely sus- Karen Sue Smith sophomore, too young to vote or drink, tained by the hope of the power, status managed to become inebriated from her and financial reward victory would bring, Online Editor first big whiff of party politics. -

March 7, 2003 Vol

Inside Archbishop Buechlein . 4, 5 Editorial . 4 Question Corner . 13 The Sunday and Daily Readings . 13 Serving the CChurchCriterion in Centralr andi Southert n Indianae Since 1960rion www.archindy.org March 7, 2003 Vol. XXXXII, No. 21 $1.00 Pope sends Cardinal Laghi to confer with Bush on Iraq VATICAN CITY (CNS)—Pope John ambassador to the United States and a long- White House spokesman Ari Fleischer Italian Cardinal Pio Paul II sent a personal envoy, Italian time friend of Bush’s father, former said no meeting with Cardinal Laghi was CNS photo Laghi is pictured in an Cardinal Pio Laghi, to Washington to confer President George H.W. Bush, was expected scheduled that day and he would keep undated file photo. with President George W. Bush and press to arrive in Washington on March 3 bearing reporters informed “as events warrant and Pope John Paul II for a peaceful solution to the Iraqi crisis. a papal message for the current president. as events come closer.” dispatched the cardinal The move, which had been under dis- In Washington, a spokeswoman for the Cardinal Laghi told the Italian newspa- to Washington to cussion at the Vatican for weeks, was the current papal nuncio, Archbishop Gabriel per Corriere della Sera, “I will insist, in confer with President pope’s latest effort to head off a war he Montalvo, said only the Vatican could the pope’s name, that all peaceful means George W. Bush and fears could cause a humanitarian crisis confirm Cardinal Laghi’s schedule in be fully explored. Certainly there must be press for a peaceful and provoke new global tensions. -

Catholic Mediation in the Basque Peace Process: Questioning the Transnational Dimension

religions Article Catholic Mediation in the Basque Peace Process: Questioning the Transnational Dimension Xabier Itçaina 1,2 1 CNRS—Centre Emile Durkheim, Sciences Po Bordeaux, 11 allée Ausone, 33607 Pessac, France; [email protected] 2 GEZKI, University of the Basque Country, 20018 San Sebastian, Spain Received: 30 March 2020; Accepted: 17 April 2020; Published: 27 April 2020 Abstract: The Basque conflict was one of the last ethnonationalist violent struggles in Western Europe, until the self-dissolution in 2018 of ETA (Euskadi ta Askatasuna, Basque Country and Freedom). The role played by some sectors of the Roman Catholic Church in the mediation efforts leading to this positive outcome has long been underestimated, as has the internal pluralism of the Church in this regard. This article specifically examines the transnational dimension of this mediation, including its symbolic aspect. The call to involve the Catholic institution transnationally was not limited to the tangible outcomes of mediation. The mere fact of involving transnational religious and non-religious actors represented a symbolic gain for the parties in the conflict struggling to impose their definitions of peace. Transnational mediation conveyed in itself explicit or implicit comparisons with other ethnonationalist conflicts, a comparison that constituted political resources for or, conversely, unacceptable constraints upon the actors involved. Keywords: Basque conflict; nationalism; Catholic Church; Holy See; transnational mediation; conflict resolution 1. Introduction The Basque conflict was one of the last ethnonationalist violent struggles in Western Europe, until the definitive ceasefire (2011), decommissioning (2017), and self-dissolution (2018) of the armed organization ETA (Euskadi ta Askatasuna, Basque Country and Freedom). -

Torture Is a Moral Issue: a Catholic Study Guide

TORTURE IS A MORAL ISSUE: A CATHOLIC STUDY GUIDE INTRODUCTION This four-chapter discussion guide on torture was developed in early 2008, as a collaboration between the Catholic members of the National Religious Campaign Against Torture and the Office of International Justice and Peace of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. The chapters are designed for use by discussion groups and classes in Catholic settings, as well as by individuals, families, and others. The intent of this material is to prompt thinking and reflection on torture as a moral issue. What has Pope Benedict XVI said about the use of torture in prisons? What does the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church say about this? Have the Catholic bishops of the United States spoken out on torture? You’ll find answers to questions like those in the chapters that follow, along with reflections on torture and prisoner abuse by numerous Catholic bishops, theologians, and other commentators. Chapter 1 is devoted to Catholic thought on the dignity of every human person. For when Catholic leaders today turn attention to the use of torture in prisons of any kind anywhere in the world, they consistently view it as a violation of the human person’s God-given dignity. Chapter 2 focuses on torture itself, and the reasons why it is a source of such concern for the Church at this point in the third millennium. What forms does torture take? What reasons are given for the torture or abusive treatment of prisoners today? What specific objections are lodged by Catholic leaders against torture? Chapter 3 closely examines Jesus’ Gospel instruction to love our enemies. -

Discours De Philippe Levillain Membre De L'institut Aux Obsèques

Discours de Philippe Levillain Membre de l’Institut aux Obsèques du Cardinal Roger Etchegaray Lundi 9 septembre 2019 Éminence, Messeigneurs, Monsieur le Ministre, Monsieur le Préfet, Monsieur le Maire de Bayonne, Il n’est pas usuel que les obsèques, d’un cardinal de la sainte Église romaine, aient lieu dans la cathédrale de son pays natal. Le cardinal Etchegaray, que j’ai connu de longue date, quand il fut expert au Concile, et moi jeune attaché de presse, n’aimait pas les honneurs. Il les prenait, parce qu’on les lui proposait. Il les prenait aussi parce qu’il estimait qu’il était de la dignité de sa fonction d’assumer le rang qui lui a été proposé par l’Église catholique romaine au Vatican. Il y vécut trente ans, sans être véritablement Romain, attaché à Rome pour sa beauté et surtout pour le tombeau de Pierre et le Souverain pontife. Il fut le compagnon de route permanent de Jean-Paul II, qui le créa cardinal le 30 juin 1979. Et il appréciait souverainement cette encyclique du Saint-Père Redemptor hominis, publié en mars 1979, peu de temps avant son élévation au cardinalat. Il en aimait le thème, la rédemption, puisque l’incarnation est une recréation, dont il faut que chacun soit conscient au fil de sa vie et en fasse témoignage et action permanente. Il ne sollicita pas l’entrée à l’Académie des Sciences morales et politiques. On lui demanda d’être candidat. C’était en 1994, et le grand-rabbin Kaplan venait de mourir. Disons que l’Académie des Sciences morales et politiques manquait d’énergie spirituelle. -

Spirit of Assisi”

Sulle vie della pace nello “spirito di Assisi” On the paths of peace In the “Spirit of Assisi” !1 INTRODUCTION The photo of the World Day of Prayer for Peace in Assisi on October 27, 1986, portraying Pope John Paul II with the leaders of religions in their colorful clothes, is one of the best-known religious images of the twentieth century. Assisi 1986: the leaders of religions with John Paul II In Assisi, various religious communities prayed in different places at the same time, affirming that only peace is holy and that at the heart of every religious tradition is the search for peace. It was a strong and unequivocal message that delegitimizes violence and war perpetrated in the name of religion. It was a simple and new reality: praying for peace, no longer against each other as it had been for centuries, perhaps millennia, but side by side.. This new image has become almost a modern icon: the leaders of the various world religions gathered together. That image had a beauty, almost an aesthetic of dialogue. Leaders joining together illustrated to their respective faithful that living together was possible and that all are part of one big family. John Paul II said: “Perhaps never before in the history of humanity, the intrinsic link between what is authentically religious and the great good of peace was made evident." Karol Wojtyla's dream was the birth of a movement of interreligious peace, which would flow from that day in Assisi. At the end of the day he said, "Peace is a building site open to everyone, not only to specialists, scholars and strategists.”1 !2 More than thirty years have passed. -

Papal Transitions

Backgrounder Papal Transition 2013 prepared by Office of Media Relations United States Conference of Catholic Bishops 3211 Fourth Street NE ∙ Washington, DC 20017 202-541-3200 ∙ 202-541-3173 fax ∙ www.usccb.org/comm Papal Transitions Does the Church have a formal name for the transition period from one pope to another? Yes, in fact, this period is referred to by two names. Sede vacante, in the Church’s official Latin, is translated "vacant see," meaning that the see (or diocese) of Rome is without a bishop. In the 20th century this transition averaged just 17 days. It is also referred to as the Interregnum, a reference to the days when popes were also temporal monarchs who reigned over vast territories. This situation has almost always been created by the death of a pope, but it may also be created by resignation. When were the most recent papal transitions? On April 2, 2005, Pope John Paul II died at the age of 84 after 26 years as pope. On April 19, 2005, German Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, formerly prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, was elected to succeed John Paul II. He took the name Pope Benedict XVI. There were two in 1978. On August 6, 1978, Pope Paul VI died at the age of 80 after 15 years as pope. His successor, Pope John Paul I, was elected 20 days later to serve only 34 days. He died very unexpectedly on September 28, 1978, shocking the world and calling the cardinals back to Rome for the second time in as many months. -

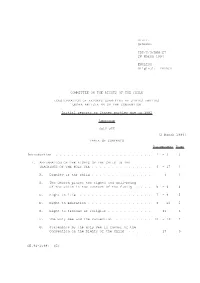

Distr. GENERAL CRC/C/3/Add.27 28 March 1994 ENGLISH Original

Distr. GENERAL CRC/C/3/Add.27 28 March 1994 ENGLISH Original: FRENCH COMMITTEE ON THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD CONSIDERATION OF REPORTS SUBMITTED BY STATES PARTIES UNDER ARTICLE 44 OF THE CONVENTION Initial reports of States parties due in 1992 Addendum HOLY SEE [2 March 1994] TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraphs Page Introduction ........................ 1 -3 3 I. AFFIRMATION OF THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD IN THE TEACHINGS OF THE HOLY SEE............... 4 -17 3 A. Dignity of the child............... 4 3 B. The Church places the rights and well-being of the child in the context of the family .... 5 -6 4 C. Right to life .................. 7 -8 5 D. Right to education................ 9 -10 5 E. Right to freedom of religion........... 11 6 F. The Holy See and the Convention ......... 12-16 7 G. Statements by the Holy See in favour of the Convention on the Rights of the Child ...... 17 9 GE.94-15987 (E) CRC/C/3/Add.27 page 2 CONTENTS (continued) Paragraphs Page II. ACTIVITY OF THE HOLY SEE ON BEHALF OF CHILDREN .... 18-43 10 A. Holy See and Church structures dealing with children..................... 19-23 10 B. Implementation of the Convention......... 24-43 12 III. ACTIVITIES OF THE PONTIFICAL COUNCIL FOR THE FAMILY FOR THE PROTECTION OF THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD....... 44-59 15 A. Meeting on the rights of the child (Rome, 18-20 June 1992) ............. 45-46 15 B. International meeting on the sexual exploitation of children through prostitution and pornography (Bangkok, 9-11 September 1992).......... 47-50 16 C. -

Le Texte De L'allocution in Memoriam S.E. Le Cardinal Roger Etchegaray

ACADÉMIE DES SCIENCES MORALES ET POLITIQUES Allocution de M. Georges-Henri Soutou, Président de l’Académie, en mémoire de son confrère le cardinal Roger Etchegaray (séance du lundi 16 septembre 2019) Mes chers confrères, « Je suis né à Jérusalem, pas simplement à Espelette. J’ai donc deux patries qui doivent se rejoindre et constituer l’unité de ma propre vie »1. Ainsi s’exprimait le cardinal Etchegaray dans un entretien télévisé en 2008, peu après une chute au cours de laquelle il s’était fracturé une vertèbre. Il en est dorénavant ainsi, puisque notre confrère s’est éteint, le 4 septembre dernier, dans sa retraite de Cambo-les- Bains au Pays Basque et a franchi les portes de la Jérusalem céleste. Cette nouvelle nous a bien entendu attristés car elle retranche de nos vies une personnalité d’une exceptionnelle envergure et d’une singulière bonté. Mais, attendant ce moment, notre confrère disait dans le même entretien : « La vérité, c’est que ma joie pleine ce sera quand même, après avoir traversé ces continents et les peuples de ce petit univers où nous vivons, de pouvoir vivre, non pas seulement passer, dans la Maison du Seigneur, de mon Dieu ». C’est fort de cette espérance, de la promesse du baptême rappelée lors de l’absoute et muni des derniers sacrements que le cardinal nous a quittés. De sa naissance à Espelette en 1922 à son enterrement en cette même ville 97 ans plus tard, Roger Etchegaray aura donc cheminé sur les routes du monde. Cette métaphore de la marche et du chemin est omniprésente dans ses déclarations et ses écrits. -

Religion, Culture, and Society: the Case of Cuba

libro_Cuba_ok 1/12/03 6:09 PM Page i RELIGION, CULTURE, AND SOCIETY: THE CASE OF CUBA Woodrow Wilson Center Reports on the Americas • # 9 libro_Cuba_ok 1/12/03 6:09 PM Page ii Printed in Argentina Designed milstein)ravel www.milsteinravel.com.ar ©2003 Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington, D.C. www.wilsoncenter.org libro_Cuba_ok 1/12/03 6:09 PM Page iii RELIGION, CULTURE, AND SOCIETY: THE CASE OF CUBA W oodrow Wilson Center Reports on the Americas • # 9 A Conference Report Conference Organizer & Editor Margaret E. Crahan with the assistance of Elizabeth Bryan Mauricio Claudio & Andrew Stevenson Latin American Program libro_Cuba_ok 1/12/03 6:09 PM Page iv THE WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS Lee H. Hamilton, Director BOARD OF TRUSTEES Joseph B. Gildenhorn, Chair; David A. Metzner, Vice Chair. Public Members: James H. Billington, Librarian of Congress; John W. Carlin, Archivist of the United States; Bruce Cole, Chair, National Endowment for the Humanities; Roderick R. Paige, Secretary, U.S. Department of Education; Colin L. Powell, Secretary, U.S. Department of State; Lawrence M. Small, Secretary, Smithsonian Institution; Tommy G. Thompson, Secretary, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Private Citizen Members: Joseph A. Cari, Jr., Carol Cartwright, Donald E. Garcia, Bruce S. Gelb, Daniel L. Lamaute, Tamala L. Longaberger, Thomas R. Reedy WILSON COUNCIL Bruce S. Gelb, President. Diane Aboulafia-D'Jaen, Elias F. Aburdene, Charles S. Ackerman, B.B. Andersen, Cyrus A. Ansary, Lawrence E. Bathgate II, John Beinecke, Joseph C. Bell, Steven Alan Bennett, Rudy Boschwitz, A. Oakley Brooks, Melva Bucksbaum, Charles W. -

Rore Sanctifica » Le Tome I

$PNJUÏJOUFSOBUJPOBMEFSFDIFSDIFTTDJFOUJmRVFTTVSMFTPSJHJOFTFUMBWBMJEJUÏEF1POUJmDBMJT3PNBOJ *OUFSOBUJPOBM$PNNJUUFFGPS4DJFOUJmD3FTFBSDIBCPVUUIF(FOFTJTBOEUIF7BMJEJUZPG1POUJmDBMJT3PNBOJ *OUFSOBUJPOBMFT,PNJUFFGàSXJTTFOTDIBGUMJDIF'PSTDIVOHFOàCFSEJF6STQSàOHFVOE(àMUJHLFJUEFT1POUJmDBMJT3PNBOJ Ɇɟɠɞɭɧɚɪɨɞɧɵɣ.RɦɢɬpɬɡɚɧɚɭɱɧɵHɂFFɥpɞɨɜDɧɢɹɩɨɩɨɜɨɞɭɉɪɨɢɫɯɨɠɞpɧɢɹɢȾHɣFɬɜɢɬHɥɶɧɨFɬɢ1POUJmDBMJT3PNBOJ $PNJUBUPJOUFSOB[JPOBMFEJ3JDFSDJTDJFOUJmDJTVMMF0SJHJOJJ7BMJEJUBEFM1POUJmDBMJT3PNBOJ (SVQPJOUFSOBDJPOBMEFJOWFTUJHBDJPOFTDJFOUJmDBTTPCSFMPTPSJHFOFTZMBWBMJEF[EFM1POUJmDBMJT3PNBOJ 1POUJmDBMJT3PNBOJ 3PSF4BODUJmDB *OWBMJEJUÏEVSJUF EF DPOTÏDSBUJPOÏQJTDPQBMF EF 1POUJmDBMJT3PNBOJ QSPNVMHVÏQBS(JPWBOOJ#BQUJTUB.POUJOJo1BVM7*o MFKVJO ÏEJUJPOGSBOÎBJTF 5PNF*o%ÏNPOTUSBUJPOFUCJCMJPHSBQIJF ²EJUJPOT4BJOU3FNJ 303&4"/$5*'*$"o5PNF*o*OWBMJEJUÏEVSJUFEFDPOTÏDSBUJPOÏQJTDPQBMFEF Prière à la Très Sainte Vierge Marie Remède contre les Esprits de ténèbres et les forces de haine et de peur. «Auguste Reine des cieux, souveraine Maîtresse des Anges, vous qui, dès le commencement, avez reçu de Dieu le pouvoir et la mission d’écraser la tête de Satan, nous vous le demandons humblement, envoyez vos Légions saintes, pour que, sous vos ordres, et par votre puissance, elles poursuivent les démons, les combattent partout, répriment leur audace et les refoulent dans l’abîme». Qui est comme Dieu ? O bonne et tendre Mère, vous serez toujours notre amour et notre espérance. O divine Mère, envoyez les saints Anges pour me défendre et repousser loin de moi le cruel ennemi. Saints Anges et Archanges défendez-nous,