Harold Pinter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ALEJANDRO URDAPILLETA INDEX TAXONOMY ARGENTINA Tradition

1954 ALEJANDRO URDAPILLETA INDEX TAXONOMY ARGENTINA tradition BIO MAIN WORKS He was born in 1954, in Montevideo, Uruguay. He is one of the most He has published Vagones transportan important representatives of the new Argentinean theatre. From humo (2000), Legión Re-ligión. Las 1984 he began to participate, individually or in groups, together with 13 Oraciones (2007), a small booklet Batato Barea, Humberto Tortonese and other artists, in the so-called with monologues, poems, stories and “underground” circuit, until the beginning of the nineties. Among his drawings edited in facsimile form. most important shows are Alfonsina y el mal, El método de Juana, La Among his latest acting works, we carancha, Mamita querida, Poemas decorados, Carne de chancha, can highlight Mein Kampf (a farce) by La moribunda. In the official theatre he was part of the cast of George Tabori and King Lear by William Hamlet o la guerra de los teatros (Teatro San Martín, dir. Ricardo Shakespeare (respectively in 2000 and Bartís), El relampago by Strindberg (dir. Augusto Fernandes), Martha 2006, both directed by Jorge Lavelli, at Stutz by Javier Daulte (dir. de Diego Kogan, 1997), Lunch at Ludwig the Teatro San Martín), and Atendiendo W.’s house by Thomas Bernhard (dir. de Roberto Villanueva)and al Sr. Sloane (2007, directed by Claudio Mein Kampf (a farce) by George Tabori (Teatro San Martín, dir. Jorge Tolcachir, Ciudad Konex). He filmed Lavelli). As an actor he has been awarded many times. numerous films, The Sleepwalker and Farewell Dear Moon (1998 and 2003, both directed by Fernando Spiner) and The Holy Girl (2004, directed by Lucrecia Martel) LINKS Actores. -

European Modernism and the Resident Theatre Movement: The

European Modernism and the Resident Theatre Movement: The Transformation of American Theatre between 1950 and 1970 Sarah Guthu A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Thomas E Postlewait, Chair Sarah Bryant-Bertail Stefka G Mihaylova Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Drama © Copyright 2013 Sarah Guthu University of Washington Abstract European Modernism and the Resident Theatre Movement: The Transformation of American Theatre between 1950 and 1970 Sarah Guthu Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Thomas E Postlewait School of Drama This dissertation offers a cultural history of the arrival of the second wave of European modernist drama in America in the postwar period, 1950-1970. European modernist drama developed in two qualitatively distinct stages, and these two stages subsequently arrived in the United States in two distinct waves. The first stage of European modernist drama, characterized predominantly by the genres of naturalism and realism, emerged in Europe during the four decades from the 1890s to the 1920s. This first wave of European modernism reached the United States in the late 1910s and throughout the 1920s, coming to prominence through productions in New York City. The second stage of European modernism dates from 1930 through the 1960s and is characterized predominantly by the absurdist and epic genres. Unlike the first wave, the dramas of the second wave of European modernism were not first produced in New York. Instead, these plays were often given their premieres in smaller cities across the United States: San Francisco, Seattle, Cleveland, Hartford, Boston, and New Haven, in the regional theatres which were rapidly proliferating across the United States. -

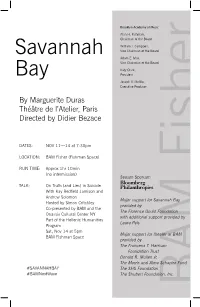

Savannah TALK: (No Intermission) Program

Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Savannah Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Katy Clark, Bay President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer By Marguerite Duras Théâtre de l’Atelier, Paris Directed by Didier Bezace DATES: NOV 11—14 at 7:30pm LOCATION: BAM Fisher (Fishman Space) RUN TIME: Approx 1hr 10min (no intermission) Season Sponsor: TALK: On Truth (and Lies) in Suicide With Kay Redfield Jamison and Andrew Solomon Major support for Savannah Bay Hosted by Simon Critchley provided by Co-presented by BAM and the The Florence Gould Foundation Onassis Cultural Center NY with additional support provided by Part of the Hellenic Humanities Laura Pels Program Sat, Nov 14 at 5pm Major support for theater at BAM BAM Fishman Space provided by The Francena T. Harrison Foundation Trust Donald R. Mullen Jr. The Morris and Alma Schapiro Fund #SAVANNAHBAY The SHS Foundation #BAMNextWave The Shubert Foundation, Inc. BAM Fisher Savannah Bay ABOUT Savannah Bay NY Premiere DIRECTOR’S NOTE Two women in a pristine white room: The overarching subject of Savannah In French with English titles one young, one old. “Who was she?” Bay is the union of two women and one asks the other, referring to a third the role play in which they engage— DIRECTOR who had long ago met a boy, fallen in perhaps daily—to recognize one Didier Bezace love, and bore his child before drown- another. Stemming from a hidden and ing herself. buried traumatic event, which they ARTISTIC MANAGEMENT bring to the surface from a shred of Dyssia Loubatière Unfolding in the melancholic half- memory, they attempt to win each light of memory, Savannah Bay is a other over, to recognize and to love PERFORMERS mesmerizing two-character drama one another. -

Page 1 of 562 JEK James and Elizabeth Knowlson Collection This Catalogue Is Based on the Listing of the Collection by James

University Museums and Special Collections Service JEK James and Elizabeth Knowlson Collection This catalogue is based on the listing of the collection by James and Elizabeth Knowlson 1906-2010 JEK A Research material created by James and Elizabeth Knowlson JEK A/1 Material relating to Samuel Beckett JEK A/1/1 Beckett family material JEK A/1/1/1 Folder of Birth Certificates, Parish registers and Army records Consists of a copy of the Beckett Family tree from Horner Beckett, a rubbing of the plaque on William Beckett’s Swimming Cup, birth certificates of the Roes and the Becketts, including Samuel Beckett, his brother, mother and father and photograph of the Paris Register Tullow Parish Church and research information gathered by Suzanne Pegley Page 1 of 562 University Museums and Special Collections Service James Knowlson note: Detailed information from Suzanne Pegley who researched for James and Elizabeth Knowlson the families of both the Roes – Beckett’s mother was a Roe - and the Becketts in the records of the Church Body Library, St Peter’s Parish, City of Dublin, St Mary’s Church Leixlip, the Memorial Registry of Deeds, etc. Very detailed results. 2 folders 1800s-1990s JEK A/1/1/2 Folder entitled May Beckett’s appointment as a nurse Consists of correspondence James Knowlson note: Inconclusive actually 1 folder 1990s JEK A/1/1/3 Folder entitled Edward Beckett Consists of correspondence James Knowlson note: Beckett’s nephew with much interesting information. 1 folder 1990s-2000s JEK A/1/1/4 Folder entitled Caroline Beckett Murphy Consists -

Dossier Artistique (.Pdf)

de Juan Mayorga conception et mise en scène Jorge Lavelli Du 9 novembre Chemin du ciel au 16 décembre 2007 (Himmelweg) Horaire du mardi au samedi 20h30 de Juan Mayorga dimanche 16h30. texte français Yves Lebeau Les Solitaires intempestifs (relâche le lundi). conception et mise en scène Jorge Lavelli Tarifs —avec plein tarif 18 ¤, Alain Mottet Le délégué de la Croix-Rouge tarifs réduits 13¤ et 10 ¤ mercredi tarif unique 10¤. Garlan Le Martelot Un garçon Florent Arnoult Un autre garçon Rencontre-débat Sophie Neveu Elle(s) avec l’équipe de création, Philippe Canales Lui mardi 13 novembre après la représentation, Charlotte Corman Rebecca, la fillette en présence de l’auteur. Pierre-Alain Chapuis Le Commandant Dominique Boissel Gottfried Théâtre de la Tempête Cartoucherie Route du Champ- —collaboration artistique Dominique Poulange de-Manœuvre —collaboration scénographique Pace 75012 Paris —costumes Fabienne Varoutsikos – réservation —collaboration lumières Gérard Monin 01 43 28 36 36 – www.la-tempete.fr —bande son Jean-Marie Bourdat Collectivités Production le méchant théâtre avec le soutien de la Drac Île-de-France, l’Aide nationale Antonia Bozzi à la création du Centre national du Théâtre, la participation artistique du 01 43 74 73 83 Jeune Théâtre national, la collaboration de l'INAEM, Ministerio de la Cultura deEspaña. Administration Sélection 2007 d'ANETH – Aux nouvelles écritures théâtrales. Elias Oziel La traduction de cette pièce a été réalisée dans le cadre de l'Atelier européen de la [email protected] traduction / Scène nationale d'Orléans, avec le concours de l'Union européenne – Commission éducation et culture. L'ouvrage est publié avec le soutien du Centre Attaché de presse national du livre. -

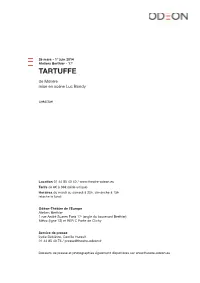

DP Tartuffe.Qxp

26 mars - 1er juin 2014 Ateliers Berthier - 17e TARTUFFE de Molière mise en scène Luc Bondy création Location 01 44 85 40 40 / www.theatre-odeon.eu Tarifs de 6€ à 36€ (série unique) Horaires du mardi au samedi à 20h, dimanche à 15h relâche le lundi Odéon-Théâtre de l’Europe Ateliers Berthier 1 rue André Suarès Paris 17e (angle du boulevard Berthier) Métro (ligne 13) et RER C Porte de Clichy Service de presse Lydie Debièvre, Camille Hurault 01 44 85 40 73 / [email protected] Dossiers de presse et photographies également disponibles sur www.theatre-odeon.eu 26 mars - 1er juin 2014 Ateliers Berthier - 17e TARTUFFE de Molière mise en scène Luc Bondy création décor Richard Peduzzi costumes Eva Dessecker lumière Dominique Bruguière maquillages/coiffures Cécile Kretschmar avec Lorella Cravotta Dorine Gilles Cohen Orgon Victoire Du Bois Mariane Jean-Marie Frin un exempt Françoise Fabian Madame Pernelle Laurent Grévill Cléante Clotilde Hesme Elmire Yannik Landrein Valère Micha Lescot Tartuffe Yasmine Nadifi Flipote Fred Ulysse Monsieur Loyal Pierre Yvon Damis et en alternance Ethan Salczer un valet Ulysse Teytaud Manfred et Tancrède Coudert production Odéon-Théâtre de l'Europe avec la participation du jeune théâtre national avec le soutien du Cercle de l’Odéon Extrait ORGON [...] Vous le haïssez tous ; et je vois aujourd'hui Femme, enfants et valets déchaînés contre lui ; On met impudemment toute chose en usage, Pour ôter de chez moi ce dévot personnage. Mais plus on fait d'effort afin de l'en bannir, Plus j'en veux déployer à l'y mieux retenir ; Et je vais me hâter de lui donner ma fille, Pour confondre l'orgueil de toute ma famille.. -

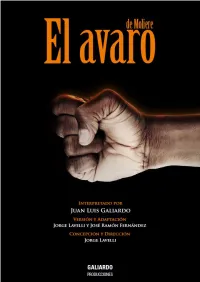

Dossierelavaro.Pdf

2 Un pensamiento sobre el Avaro 3 Equipo creativo y artístico 4 Jorge Lavelli 6 Juan Luis Galiardo 8 Dominique Poulange 9 José Ramón Fernández 11 Chusa Martín Podría pensarse que el viejo Harpagón ha llamado a la puerta de nuestro imaginario traído de la mano por la crisis de los bancos y las entidades de préstamo norteamericanas. No es así. Sé que Juan Luis Galiardo lleva pensando en este proyecto mucho tiempo; creo que fue en los descansos de los ensayos de “Edipo Rey”, el pasado verano, cuando comenzaron a hablar Jorge Lavelli y él sobre esta obra. Y es que el teatro no busca la actualidad, eso es falso: el teatro busca aquello de eterno que hay en nuestro paso por el mundo. Harpagón nos interesa porque habla de nosotros, estén donde estén los índices de la Bolsa. ¿De nosotros? Sí, de nuestro miedo, de nuestra sensatez exagerada, o no tanto: como Harpagón es un ser humano, que no otra cosa dibujó Molière, teme que el gasto excesivo lo lleve a la pobreza, al hambre. Bien es verdad que cualquiera consideraría fuera de lugar a un hijo que es capaz de, para atender a sus gastos de ropa y adornos, poner como garantía de préstamo la cercana muerte de su propio padre - ¿o puede ser que eso ocurra en algunos lugares? –; o que un cocinero planee una cena tan abundante que mataría a un cocodrilo – eso, hoy día, parece impensable, es cierto – sin atender ni al gasto ni a la salud de los comen- sales; sin embargo, condenamos la actitud avariciosa del individuo que se revela contra eso, nos parece risible el avaro. -

El Avaro De Molière

El avaro de Molière Versión y adaptación Jorge Lavelli y José Ramón Fernández Concepción y dirección Jorge Lavelli Funciones 8 de abril al 23 de mayo de 2010 De martes a sábados, a las 20.30 h. Domingos, a las 19.30 h Teatro María Guerrero Tamayo y Baus, 4 28004 Madrid Centro Dramático Nacional | Prensa Teléfonos 913109429– 913109425– 91 310 94 13– 609052508 [email protected] http://cdn.mcu.es/ El avaro de Molière Versión y adaptación Jorge Lavelli y José Ramón Fernández Concepción y dirección Jorge Lavelli Equipo artístico Colaboración artística Dominique Poulange Dispositivo escénico Ricardo Sánchez-Cuerda Iluminación Jorge Lavelli y Roberto Traferri Música original Zygmunt Krauze Vestuario Francesco Zito Ayudante de dirección Gloria Vega Reparto (por orden alfabético) Doña Claudia Carmen Álvarez Maese Simón /Comisario Manuel Brun Flecha Manolo Caro Pocapena Manuel Elías Frosina Palmira Ferrer Harpagón Juan Luis Galiardo Cleantes Javier Lara Anselmo Mario Martín Merluza Walter May Valerio Rafael Ortiz Elisa Irene Ruiz Señor Santiago Tomás Sáez Mariana Aída Villar Producción Centro Dramático Nacional, Galiardo Producciones, Centro Andaluz de Teatro, Teatro Calderón y Comunidad de Madrid 2 Molière y nuestros tiempos La teatralidad de Molière atraviesa los tiempos sin detenerse frente a ninguna barrera. O casi. Es el caso de este avaro, a la vez familiar y simbólico, pero jamás extranjero. La avaricia es una forma exasperante y perfecta del egoísmo; la ignorancia de la muerte, su compañía. Se diría que la avaricia puede atraparse como cualquier otra enfermedad, pero su cura es científicamente imposible. En el polo opuesto del comportamiento, la generosidad puede elevarse hasta el don de sí mismo en una suerte de santidad. -

Dp Prix Des Boutes.Pdf

sommaire informations pratiques p. 2 distribution p. 3 synopsis p. 4 notes d’intention p. 5 note d’intention de l’auteur, Frédéric Pommier p. 5 note d’intention du metteur en scène, Jorge Lavelli p. 6 biographies p. 7 Frédéric Pommier, texte p. 7 Jorge Lavelli, conception, mise en scène et lumières p. 7 Dominique Poulange, collaboration artistique p. 7 Rodolfo Natale, scénographie p. 8 Fabienne Varoutsikos, costumes p. 8 Gérard Monin, lumières p. 8 distribution Francine Bergé p. 9 Raoul Fernandez p. 9 Catherine Hiegel p. 10 Francis Leplay p. 10 Sophie Neveu p. 11 Liliane Rovère p. 11 la saison 2012-2013 de l’Athénée p. 12 1 informations pratiques du jeudi 21 mars au samedi 13 avril 2013 mardi à 19h, du mercredi au samedi à 20h I relâche les lundis et dimanches matinées exceptionnelles : dimanche 7 avril à 16h et samedi 13 avril à 15h tarifs : de 7 à 32 € - plein tarif : de 14 à 32 € - tarif réduit* : de 12 à 27 € *plus de 65 ans et abonnés pour les spectacles hors-abonnement (sur présentation d’un justificatif) - tarif jeune -30 ans** : de 7 à 16 € **50% de réduction sur le plein tarif pour les moins de 30 ans, et les bénéficiaires du RSA (sur présentation d’un justificatif) - groupes / collectivités et demandeurs d’emploi : de 10 à 25 € autour du spectacle : dialogues : À l'issue de la représentation, Frédéric Pommier et l'équipe artistique vous retrouvent au foyer-bar pour échanger à chaud sur le spectacle. mardi 2 avril I entrée libre hors les murs : En partenariat avec la Bibliothèque nationale de France, conférence sur l'humour noir et l'ironie réaliste, en présence de Frédéric Pommier et Jorge Lavelli. -

Programme Trahisons 14/15

Trahisons En couverture : Léonie Simaga, Denis Podalydès. Ci-dessus : Léonie Simaga, Laurent Stocker. © Cosimo Mirco Magliocca THÉÂTRE DU VIEUX-COLOMBIER Les Nouveaux Cahiers de la Comédie-Française Cahier n°1Bernard-Marie KOLLTÈSTÈS | Cahier n°2 BEAUMARCHAIS | Cahier n°3 Ödön von HORVVÁÁÁTTH | Cahier n°4 Alfred de MUSSEMUSSET | Cahier n°5 Alfred JARRY | Cahier n°6 Dario FO | Cahier n°7 Georges FEYDEAU | Cahier n°8 TTennesseeennessee WILLIAMS | Cahier n°9 Carlo GOLDONI | Cahier n°10 VOictor HGUi | Cahier n°11 W lliam SHAKESPEAREESPEARE - Prix de vente 10 €. Disponibles danns les boutiques de la Comédie-Française, sur www.boutique-comedie-francaise.frr,, ainsi qu’en librairie Éditions L’avant-scène théâtre Le théâtre français du Moyen Âge et de la Renaissance XIIe - XVIe siècles à paraître en octobre 2014 Denis Podalydès, Laurent Stocker. © Cosimo Mirco Magliocca Trahisons de Harold Pinter Texte français de Éric Kahane Pour la première fois a la Comédie-Française DU 17 SEPTEMBRE AU 26 OCTOBRE 2014 durée estimée 1h30 Mise en scène de Frédéric Bélier-Garcia Collaboratrice artistique Caroline GONCE I Décor Jacques GABEL I Lumières Roberto VENTURI I Costumes Catherine LETERRIER et Sarah LETERRIER I Son Bernard VALLERY I Le décor a été construit par l’atelier François Devineau. avec Denis PODALYDÈS Robert Laurent STOCKER Jerry Christian GONON le Garçon de café et le Garçon de restaurant Léonie SIMAGA Emma L’Arche est agent théâtral du texte représenté. Une rencontre avec Frédéric Bélier-Garcia et des membres de l’équipe artistique aura lieu mardi 14 octobre à l’issue de la représentation. Le spectacle sera repris au Nouveau Théâtre d’Angers les 30 et 31 octobre 2014. -

JORGE LAVELLI Bibliographie Sélective

Bibliothèque nationale de France direction des collections département Arts du spectacle – Maison Jean Vilar juin 2015 JORGE LAVELLI Bibliographie sélective © Photographie de Daniel Cande Metteur en scène d’origine argentine, né en 1932 à Buenos Aires, ancien élève de Charles Dullin et de Jacques Lecoq, Jorge Lavelli se passionne très vite pour les alliances entre musique et théâtre. En 1969 déjà, il crée au Festival d'Avignon une première forme de “théâtre musical” avec Orden, de Pierre Bourgeade et Girolamo Arrigo. Ce double intérêt le poussera si loin qu’il sera le metteur en scène de hauts lieux de création tels que la Comédie française, l’Opéra Garnier de Paris, et sera invité une dizaine de fois au Festival d’Avignon. Il y donnera à quatre reprises des spectacles dans la Cour d’honneur : Medea et Le Triomphe de la sensibilité en 1967, Le conte d’hiver en 1980, Comédies barbares en 1991. En 1987, il fonde le Théâtre national de la Colline et en sera le directeur jusqu’en 1996. A l’occasion du XIVe Patrimoine en vitrine consacré à Jorge Lavelli, la bibliothèque de la Maison Jean Vilar, antenne du département des Arts du spectacle de la Biliothèque nationale de France, propose une bibliographie sélective d’ouvrages, d’articles et de photographies consacrés aux mises en scène de Jorge Lavelli au Festival d’Avignon et ailleurs. Les textes des pièces de théâtre recensés sont les versions choisies par Lavelli lui-même pour ses mises en scène. Le recensement se limite à la documentation disponible à la Maison Jean Vilar. -

Mise En Page 1

Théâtral magazine L’actualité du théâtre mai - juin - juillet 2020 Pierre Arditi Olivier Py Michel Fau Pascal Rambert Julie Deliquet Jean-Pierre Vincent Jean-François Sivadier Caroline Vigneaux Chloé Dabert Emmanuel Demarcy-Mota Clément Hervieu-Léger Philippe Torreton La scène confinée DOSSIER La CONTAMINATION au théâtre M 02434 - 83 - F: 4,60 E - RD Théâtral magazine n 83 www.theatral-magazine.com ° ’:HIKMOD=YUY[UV:?k@a@s@d@a" ommaire Théâtral magazine S N° 83 - MAI / JUIN / JUILLET 2020 04 AGENDA des captations 06 ACTUALITÉS 07. Edito de Gilles Costaz 08 UNE 08. Philippe Torreton 12 SPÉCIAL : LA SCÈNE CONFINÉE ! Théâtral magazine est édité par : 14 . Clément Hervieu-Léger 23 . Gaëlle Guillou Coulisses Editions 16 . Olivier Py 24 . Laëtitia Guédon 7 rue de l’Eperon 75006 Paris France Tél : + 33 1 43 27 07 03 18 . Chloé Dabert 25 . Jean Varela Email : [email protected] 20 . Marc Lainé 26 . Luis Torreao Site Internet : www.theatral-magazine.com 21 . Mathieu Bauer 27 . Marie-Lise Fayet 22 . Emmanuel Demarcy-Mota 28 . Caroline Vigneaux Directeur de la publication : Hélène Chevrier Directeur de la rédaction : Enric Dausset 30 ECLAIRAGE Rédactrice en chef : Hélène Chevrier [email protected] 30. La double inconstance, mise en scène Galin Stoev 31. Eclairage par Gilles Costaz Rédaction : Hélène Chevrier Vincent Bouquet 36 PROJETS REPORTÉS Gilles Costaz Enric Dausset 36 . Pierre Arditi 43 . David Ayala Igor Hansen-Love 37 . Olivier Py 44 . Michel Fau Jean-François Mondot Jacques Nerson 38 . Julien Gosselin 45 . Pascal Rambert Nathalie Simon 40 . François Gremaud 46 . Compagnie XY Patrice Trapier 41 . Julie Deliquet 47 .