Recognizing Regions: ASEAN’S Struggle for Recognition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July 16-31, 1973

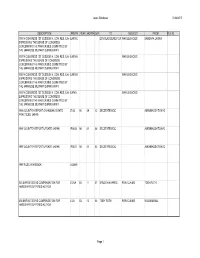

RICHARD NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY DOCUMENT WITHDRAWAL RECORD DOCUMENT DOCUMENT SUBJECT/TITLE OR CORRESPONDENTS DATE RESTRICTION NUMBER TYPE 1 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/22/1973 A Appendix “A” 2 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/27/1973 A Appendix “A” 3 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/29/1973 A Appendix “A” COLLECTION TITLE BOX NUMBER WHCF: SMOF: Office of Presidential Papers and Archives RC-13 FOLDER TITLE President Richard Nixon’s Daily Diary July 16, 1973 – July 31, 1973 PRMPA RESTRICTION CODES: A. Release would violate a Federal statute or Agency Policy. E. Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential commercial or B. National security classified information. financial information. C. Pending or approved claim that release would violate an individual’s F. Release would disclose investigatory information compiled for law rights. enforcement purposes. D. Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy G. Withdrawn and return private and personal material. or a libel of a living person. H. Withdrawn and returned non-historical material. DEED OF GIFT RESTRICTION CODES: D-DOG Personal privacy under deed of gift -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION *U.S. GPO; 1989-235-084/00024 NA 14021 (4-85) _.- _.--. --------. THE: WHITE HOUSE PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON'S DAILY DIARY (See Travel Record for Trnel AdiYity) -P PLAcE DAY BEGAN DATE (No., bay, Yr.) JULY 16. 1973 NAVAL MEDICAL CENTER TlVI! DAY BETHESDA, MARYLAND 8:00 a.m. MONDAY PHONE TIME P=Pl.ctd R~Rcctiftcl ACTlVJTY la Oat 10 LD The President met with: 8:00 8:06 Robert J. Dunn, Chief Hospital Corpsman (HMC) 8:05 8:30 Susan A. -

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade Accord

GENERAL AGREEMENT ACCORD GENERAL SUR RESTRICTED ON TARIFFS AND LES TARIFS DOUANIERS ™<$2^ TRADE ET LE COMMERCE Special Distribution MINISTERIAL MEETING REUNION MINISTERIELLE Tokyo, 12-14. September 1973 Tokyo, 12-14- septembre 1973 LJEST_QF jŒPRESENTATIVES LISTE" DES REPRESENTANTS Chairman: Mr. Masayoshi OHIRA, Minister for Foreign Affairs of Japan Président: ALGERIE Représentants S.E. M. Mustapha Belhocine, Ministre plénipotentiaire, Ministère des Affaires étrangères M. Mohamed Bouzarbia, Conseiller, Ministère des Affaires étrangères M. Abderahmane Charef, Directeur des Relations extérieures, Ministère du Commerce M. Mohamed Kamel Achour, Conseiller technique, Ministère du Commerce, M. Mustapha Dadou, Deuxième secrétaire, Ambassade à Tokyo Secretary of Meeting: Mr. H. van Tuinen, Room 319, Tel. ext 14-06 Press Officer: Mr. J. Croome, Matsu Room, 2nd Floor, Tel. ext. 362 -437-6904. (direct line) MIN(73)lHP/4/Rev.l Page 2/3 ARGENTINA Représentantes Sr. Gabriel Martinez Emba ador Représentante Especial para las Negociaciones Comerciales del-GATT, Sub-secretario de Comercio Exterior Sr. Fernando Lerena Ministro, Représentante Especial Alterno, Director de Tratados y Negociaciones de la Sub-secretaria del Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores Sr» Jorge Livingston Consejero ante el GATT, Misidn permanente ante la Oficina de las Naciones Unides en Ginebra AUSTRALIA Representatives The Eon. J.F. Cairns Minister of Overseas Trade and Minister for Secondary Industry Leader of Delegation H.E. Mr. G. Warwick Smith Ambassador, Special Trade Representative Mr. F.C. Pryor Secretary, Department of Secondary Industry Mr. S.F. Harris Deputy Secretary, Department of Overseas Trade Mr. J.C. Taylor First Assistant Secretary, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet Mr. F.M. Collins First Assistant Secretary, . -

THE JAPAN HOUSE YEARS Reorganization and Expansion: Speaking Engagements and Intellectual Exchanges

PART III: THE JAPAN HOUSE YEARS Reorganization and Expansion: speaking engagements and intellectual exchanges. 1967–73 In public affairs, the report recommended that the Society encourage a dialogue and promote The report of the Program Study Committee was exchanges between Japan and the United States to ready by September and was presented on October 30 , improve public understanding of economic and polit - 1967 , to the Board, which approved the recommen - ical issues, particularly at the private leadership level. dations. These covered cultural affairs, educational Program techniques might include co-sponsored programs, public affairs, other activities, and space, programs, lectures, and panels, as well as small staffing, and finances. The report gave special atten - meetings and conferences. A survey might be made tion to mounting pressure for the Society to be more of top Japanese business leaders in New York to active in the public affairs and economic fields and determine what interests were not already being met to exert more vigorous national leadership. by other organizations. The seminars called “Doing It also recommended de-emphasizing time- Business in Japan” for young American executives consuming retail activities and concentrating instead should be continued, and similar ones set up for young on playing an innovative and creative role in the cul - Japanese executives coming to the United States. tural area by identifying the artists and creative work Regarding space, staff, and budget, the report that should be brought to the attention of American recommended that the Society retain full control audiences. The exhibition space of the new Japan over Japan House facilities, making them available House should be utilized for loan exhibitions of high to other organizations on a “guest” basis. -

Do Development Minister Characteristics Affect Aid Giving?

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Fuchs, Andreas; Richert, Katharina Working Paper Do Development Minister Characteristics Affect Aid Giving? Discussion Paper Series, No. 604 Provided in Cooperation with: Alfred Weber Institute, Department of Economics, University of Heidelberg Suggested Citation: Fuchs, Andreas; Richert, Katharina (2015) : Do Development Minister Characteristics Affect Aid Giving?, Discussion Paper Series, No. 604, University of Heidelberg, Department of Economics, Heidelberg, http://dx.doi.org/10.11588/heidok.00019769 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/127421 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von -

Bibliothиque Du CIO / IOC Library

Wiïliftift ijiàifillifhinèsS m m j i l p i i i t e rJykîW^Î^Ss&r*i r ÊÊW S U M i H »iH îU a^w l nn'sm'fS il iiiSiîiiîiBüs^Tlt!Ts5î*î^Ki-r»iSrî!ii y%iÉ ' - il < *■ î ■ I ~ " j i ! !^ * S » l ü Ss?îr rSjÿgjfe ■ - iü'i æ i w s i W f e lB iW a il Source : Bibliothèque du CIO / IOC Library Source : Bibliothèque du CIO / IOC Library THE GAMES OF THE XVIII OLYMPIAD TOKYO 1964 The Official Report of the Organizing Committee Source : Bibliothèque du CIO / IOC Library PREFACE The Official Report of the Games of the XVIIIth Olympiad is now ready for publishing. In order to ensure that all pertinent details and data for this official report, as stipulated in the Olymjnc Charter, would be carefully preserved, this Organizing Committee set up a sub-committee for this purpose in April 1962 some two years before the Games took place. This sub-committee included a representation from each division of the Secretariat and with the Public Relations Division (later the Press and Public In formation Division) outlying the overall plan of collecting and collating the many necessary facts and details as they occurred. This sub-committee was early in 1964 reorganized to a “Report Editing Sub-Committee” to prepare for the final compilation in a form for presentation in a comprehensive report. In the collecting of overall details of the Games preparations, cooperation was required from agencies and organizations other than the actual Organizing Committee itself and in this, we are most grateful for the assistance willingly extended by the various agencies of the National Government, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, and the other Prefectural and City authorities involved with certain aspects or sports facilities used for the Games. -

Post-Reversion Okinawa and U.S.-Japan Relations

ヌ U.S.-Japan Alliance Affairs Series No. 1 May 2004 Post-Reversion Okinawa and U.S.-Japan Relations A Preliminary Survey of Local Politics and the Bases,1972-2002 Robert D. Eldridge Post-Reversion Okinawa and U.S.-Japan Relations A Preliminary Survey of Local Politics and the Bases, 1972-2002 Robert D. Eldridge ________________________ U.S.-Japan Alliance Affairs Division Center for International Security Studies and Policy School of International Public Policy, Osaka University May 2004 我胴やちょんわどの Wada ya chon wadu nu 儘ならぬ世界に Mama naran shike ni 彼ようらめゆる Ari yu urami yu ru よしのあるい Yushi nu arui --本部按司、19世紀 In a world full of obstacles, One cannot steer his course at will. Why should I think ill of others, When they fail to suit me? --Prince MUTUBU Anji, 19th Century Table of Contents I. Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………1 Purpose of Study Previous Research Materials Used Structure of Study Final Remarks and Acknowledgments II. Overview of Politics and Social Dynamics in Okinawa following Reversion………………7 A. The Reformist Years, 1972-1977 B. The Conservative Shift, 1977-1988 C. The Return of the Reformist Wave, 1988-1997 D. Accommodation, or the Return of the Conservatives, 1998-2002 E. Politics after 2002: Beyond the 30th Anniversary of the Return of Okinawa III. The Okinawa Base Problem and U.S.-Japan Relations after Reversion…………………. 58 A. U.S. Bases at the Time of Reversion B. Ensuring Land Usage—the Repeated Crises over Legislation for Compulsory Leasing C. The Arrival of the Self Defense Forces D. Base-related Frictions in the 1970s E. Base-related Frictions in the 1980s F. -

Japan Society Timeline

JAPAN SOCIETY TIMELINE 1907 1911 1918 May 19 , 1907 : Japan Society founded by Annual lecture series initiated (lectures Japan Society Bulletin of February 28 , 1918 , Lindsay Russell, Hamilton Holt, Jacob Schiff, usually held at the Hotel Astor or at The exhorted readers: “Isn’t it worth your while August Belmont, and other prominent Metropolitan Museum of Art, drawing to spend fifteen minutes a month on Japan? Americans on the occasion of the May visit several hundred people); lectures from The day has passed when we needed to think to New York by General Baron Tamesada the first year included Toyokichi Ienaga only in terms of our own country. The inter - Kuroki and Vice Admiral Goro Ijuin. on “The Positions of the United States and national mind is of today. Read this Bulletin Japan in the Far East” and Frederick W. of the Japan Society and learn something John H. Finley, president of City College, Gookin on Japanese color prints. new about your nearest Western neighbor. elected Japan Society’s first president. Japan has much to teach us. Preparedness is Japan Society’s first art exhibition held Purpose of the Society set forth as “the pro - the watchword of the day: don’t forget that (ukiyo-e prints borrowed from private motion of friendly relations between the this includes mental preparedness. It is just collections and shown at 200 Fifth Avenue), United States and Japan and the diffusion as important to think straight as to shoot attended by about 8,000 people. among the American people of a more accu - straight. -

The Development of US Extended Nuclear Deterrence Over Japan: a Study of Invisible Deterrence Between 1945 and 1970

The University Of Reading The Development of US Extended Nuclear Deterrence over Japan: A Study of Invisible Deterrence between 1945 and 1970 Hiroshi Nakatani PhD, Politics Department of Politics and International Relations February 2019 Declaration of Original Authorship Declaration: I confirm that this is my own work and the use of all materials from other sources has been properly and fully acknowledged Hiroshi Nakatani 1 This thesis is dedicated to the late Colonel Matuo Keiichi for his service to Japan. 2 Acknowledgments Throughout my PhD life, many people and institutions have thoughtfully supported and encouraged my work. It is probably most appropriate to begin by acknowledging the School of Politics, International Relations and Economics, University of Reading for its financial assistance for three years. I am also extremely indebted to the Lyndon Johnson Library, the British Association for Japanese Studies and Reading Travel Research Grants for providing me with research grants, which enabled me to travel and research abroad. Without their generous financial support, this research project would not have been possible. I would also like to express my appreciation to my supervisors. I have been fortunate to have three supervisors. It was my greatest honour to work under Professor Beatrice Heuser, for whom I came to Reading. She has taught me many invaluable things which otherwise I could have never learned. She has taught me how to conduct great research and treat your students in particular. As a matter of fact, finding a greater supervisor than her can be more difficult to finish a PhD. I would also like to thank Professor Alan Cromartie for his supervision and patience. -

Japan's Shift in the Nuclear Debate

Draft—Please do not cite or circulate without author’s permission. Japan’s Shift in the Nuclear Debate: A Changing Identity? Sayuri Romei, Center for International Security and Cooperation, Stanford University 1 Abstract: Throughout the Cold War, Japanese leaders and policy-makers have generally been careful to reflect the public’s firm opposition to anti-nuclear sentiment. However, the turn of the 21st century has witnessed a remarkable shift in the political debate, with élites alluding to a nuclear option for Japan. This sudden proliferation of nuclear statements among Japanese élites in 2002 has been directly linked by Japan watchers to the break out of the second North Korean nuclear crisis and the rapid buildup of China’s military capabilities. Is the Japanese perception of this double military threat in Northeast Asia really the main factor that triggered this shift in the nuclear debate? This paper argues that Japanese élites’ behavior rather indicates that the new threats in the regional strategic context is merely used as a pretext to solve a more deep-rooted and long-standing anxiety that stems from Japan’s own unsuccessful quest for a less reactive, and more proactive post-Cold War identity. 2 Keywords: Japanese identity, nuclear debate, post-Cold War, nuclear hedging, nuclear latency, nuclear power, political maturity, perception Introduction: The scarring events of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 shaped the history of Japan and its people's perception of nuclear weapons, which in turn shaped the country's strategic culture and security policy. However, partially because those infamous events were considered still part of the war, and certainly because of the media censorship imposed at the time by the General Headquarters,1 it was the Lucky Dragon Number 5 (Daigo Fukuryū-Maru) incident on March 1, 1954, that unleashed for the first time a fierce nationwide anti-nuclear movement. -

This Item Is a Finding Aid to a Proquest Research Collection in Microform

This item is a finding aid to a ProQuest Research Collection in Microform. To learn more visit: www.proquest.com or call (800) 521-0600 This product is no longer affiliated or otherwise associated with any LexisNexis® company. Please contact ProQuest® with any questions or comments related to this product. About ProQuest: ProQuest connects people with vetted, reliable information. Key to serious research, the company has forged a 70-year reputation as a gateway to the world’s knowledge – from dissertations to governmental and cultural archives to news, in all its forms. Its role is essential to libraries and other organizations whose missions depend on the delivery of complete, trustworthy information. 789 E. Eisenhower Parkway ■ P.O Box 1346 ■ Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 ■ USA ■ Tel: 734.461.4700 ■ Toll-free 800-521-0600 ■ www.proquest.com A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Confidential U.S. State Department Central Files JAPAN 1967–1969 Part 1: Political, Governmental, and National Defense Affairs A UPA Collection from Confidential U.S. State Department Central Files JAPAN 1967–1969 PART 1: POLITICAL, GOVERNMENTAL, AND NATIONAL DEFENSE AFFAIRS Subject-Numeric Categories: AID, CSM, DEF, and POL Guide compiled by Todd Michael Porter A UPA Collection from 7500 Old Georgetown Road • Bethesda, MD 2081420814-6126 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Confidential U.S. State Department central files. Japan 1967–1969 [microform] : subject-numeric categories AID, CSM, DEF, and POL microfilm reels ; 35 mm. Summary: Reproduces documents from among the records of the U.S. Department of State in the custody of the National Archives. -

12/22/2010 Japan Database Page 1 DESCRIPTION PREFIX YEAR

Japan Database 12/22/2010 DESCRIPTION PREFIX YEAR MONTH DAY TO SUBJECT FROM FILE ID 105TH CONGRESS 1ST SESSION H. CON. RES. 126- EA078C DOUGLAS BEREUTER WAR LEGACIES BARBARA LARKIN EXPRESSING THE SENSE OF CONGRESS CONCERNING THE WAR CRIMES COMMITTED BY THE JAPANESE MILITARY DURING WWII 105TH CONGRESS 1ST SESSION H. CON. RES. 126- EA078A WAR LEGACIES EXPRESSING THE SENSE OF CONGRESS CONCERNING THE WAR CRIMES COMMITTED BY THE JAPANESE MILITARY DURING WWII 105TH CONGRESS 1ST SESSION H. CON. RES. 126- EA078B WAR LEGACIES EXPRESSING THE SENSE OF CONGRESS CONCERNING THE WAR CRIMES COMMITTED BY THE JAPANESE MILITARY DURING WWII 105TH CONGRESS 1ST SESSION H. CON. RES. 126- EA78A WAR LEGACIES EXPRESSING THE SENSE OF CONGRESS CONCERNING THE WAR CRIMES COMMITTED BY THE JAPANESE MILITARY DURING WWII 1995 COUNTRY REPORT ON HUMAN RIGHTS Z016 95 09 12 SECSTATE/WDC AMEMBASSY/TOKYO PRACTICES: JAPAN 1997 COUNTRY REPORT UPDATE: JAPAN IP0048 98 01 05 SECSTATE/WDC AMEMBASSY/TOKYO 1997 COUNTRY REPORT UPDATE: JAPAN IP0047 98 01 02 SECSTATE/WDC AMEMBASSY/TOKYO 1997 FCSC YEARBOOK LC0009 203 MARINE SEEKS COMPENSATION FOR L024A 85 11 27 BRUCE NAVARRO POW CLAIMS TOBY ROTH HARDSHIPS SUFFERED AS POW 203 MARINE SEEKS COMPENSATION FOR L024 85 12 06 TOBY ROTH POW CLAIMS WILLIAM BALL HARDSHIPS SUFFERED AS POW Page 1 Japan Database 12/22/2010 DESCRIPTION PREFIX YEAR MONTH DAY TO SUBJECT FROM FILE ID 3E1 INELIGIBILITIES -- JAPANESE WAR CRIMINALS IP0050 98 07 02 SECSTATE WAR LEGACIES AMEMBASSY TOKYO 45TH TRUSTEESHIP COUNCIL (TC): JAPANESE IP0175 78 05 19 SECSTATE/WDC USMISSION/NEW DEMARCHE CONCERNING WAR CLAIMS YORK 45TH TRUSTEESHIP COUNCIL (TC): JAPANESE IP0176 78 05 20 SECSTATE/WDC USMISSION/NEW DEMARCHE CONCERNING WAR CLAIMS YORK 45TH TRUSTEESHIP COUNCIL: WAR CLAIMS IP0177 78 05 23 USMISSION/NEW SECSTATE/WDC YORK A/S ROTH'S MOFA MEETINGS IN TOKYO EA064 98 12 14 SECSTATE/WDC WAR LEGACIES AMEMBASSY/TOKYO AFTER 40 YEARS SOME COMFORT EA045 92 01 24 WAR LEGACIES AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE U.S. -

Paper Development Ministers 37

University of Heidelberg Department of Economics Discussion Paper Series No. 604 Do Development Minister Characteristics Affect Aid Giving? Andreas Fuchs and Katharina Richert November 2015 Do Development Minister Characteristics Affect Aid Giving?* ANDREAS FUCHS, Heidelberg University, Germany KATHARINA RICHERT#, Heidelberg University, Germany This version: November 2015 Abstract: Over 300 government members have had the main responsibility for international development cooperation in 23 member countries of the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee since the organization started reporting detailed Official Development Assistance (ODA) data in 1967. Understanding their role in foreign aid giving is crucial since their decisions might directly impact aid effectiveness and thus economic development on the ground. Our study examines whether development ministers’ personal characteristics influence aid budgets and aid quality. To this end, we create a novel database on development ministers’ gender, political ideology, prior professional experience in development cooperation, education in economics, and time in office over the 1967- 2012 period. Results from fixed-effects panel regressions show that some of the personal characteristics of development ministers matter. Most notably, we find that more experienced ministers with respect to their time in office obtain larger aid budgets. Moreover, there is evidence that female ministers as well as officeholders with prior professional experience in development cooperation and a longer time in office provide higher-quality ODA. JEL classification: D78, F35, H11, O19 Keywords: development minister, leadership, foreign aid, Official Development Assistance, aid budget, aid quality, personal characteristics, gender, partisan politics, experience 1 * We are grateful for valuable comments by Axel Dreher, Pierre-Guillaume Méon, Sarmistha Pal, Francisco J.