The GEM Index

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THESIS KD Final

The London School of Economics and Political Science Representing SlutWalk London in Mass and Social Media: Negotiating Feminist and Postfeminist Sensibilities Keren Darmon A thesis submitted to the Department of Media and Communications of the London School of Economics and Political Science for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, June 2017 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 57,074 words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Ms. Jean Morris. 2 Epigraphs It has been a hostile climate for feminism: it didn’t thrive, but it didn’t die; it survives, it is nowhere and everywhere – and the phoenix is flying again. (Campbell, 2013, p. 4) As Prometheus stole fire from the gods, so feminists will have to steal the power of naming from men, hopefully to better effect. (Dworkin, 1981, p. 17) 3 Abstract When SlutWalk marched onto the protest scene, with its focus on ending victim blaming and slut shaming, it carried the promise of a renewed feminist politics. -

Bosnia and Herzegovina and the United Nations Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework

Bosnia and Herzegovina and the United Nations 2021- Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework 2025 A Partnership for Sustainable Development Declaration of commitment The authorities in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) and the United Nations (UN) are committed to working together to achieve priorities in BiH. These are expressed by: ` The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and selected Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and targets1 as expressed in the emerging SDG Framework in BiH and domesticated SDG targets2; ` Future accession to the European Union, as expressed in the Action Plan for implementation of priorities from the European Commission Opinion and Analytical Report3; ` The Joint Socio-Economic Reforms (‘Reform Agenda’), 2019-20224; and ` The human rights commitments of BiH and other agreed international and regional development goals and treaty obligations5 and conventions. This Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework (CF), adopted by the BiH Council of Ministers at its 22nd Session on 16 December 2020 and reconfrmed by the BiH Presidency at its 114th Extraordinary Session on 5 March 2021, will guide the work of authorities in BiH and the UN system until 2025. This framework builds on the successes of our past cooperation and it represents a joint commitment to work in close partnership for results as defned in this Cooperation Framework that will help all people in BiH to live longer, healthier and more prosperous and secure lives. In signing hereafter, the cooperating partners endorse this Cooperation Framework and underscore their joint commitments toward the achievement of its results. Council of Ministers of Bosnia and Herzegovina United Nations Country Team H.E. Dr. Zoran Tegeltija Dr. -

Central African Republic

Human Development Report 2014 Sustaining Human Progress: Reducing Vulnerabilities and Building Resilience Explanatory note on the 2014 Human Development Report composite indices Central African Republic HDI values and rank changes in the 2014 Human Development Report Introduction The 2014 Human Development Report (HDR) presents the 2014 Human Development Index (HDI) (values and ranks) for 187 countries and UN-recognized territories, along with the Inequality-adjusted HDI for 145 countries, the Gender Development Index for 148 countries, the Gender Inequality Index for 149 countries, and the Multidimensional Poverty Index for 91 countries. Country rankings and values of the annual Human Development Index (HDI) are kept under strict embargo until the global launch and worldwide electronic release of the Human Development Report. It is misleading to compare values and rankings with those of previously published reports, because of revisions and updates of the underlying data and adjustments to goalposts. Readers are advised to assess progress in HDI values by referring to table 2 (‘Human Development Index Trends’) in the Statistical Annex of the report. Table 2 is based on consistent indicators, methodology and time-series data and thus shows real changes in values and ranks over time, reflecting the actual progress countries have made. Small changes in values should be interpreted with caution as they may not be statistically significant due to sampling variation. Generally speaking, changes at the level of the third decimal place in any of the composite indices are considered insignificant. Unless otherwise specified in the source, tables use data available to the HDRO as of 15 November 2013. -

Faqs) About the Gender Inequality Index (GII

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about the Gender Inequality Index (GII) What is the Gender Inequality Index? The Gender Inequality Index is a composite measure reflecting inequality in achievements between women and men in three dimensions: reproductive health, empowerment and the labour market. It varies between zero (when women and men fare equally) and one (when men or women fare poorly compared to the other in all dimensions). The health dimension is measured by two indicators: maternal mortality ratio and the adolescent fertility rate. The empowerment dimension is also measured by two indicators: the share of parliamentary seats held by each sex and by secondary and higher education attainment levels. The labour dimension is measured by women’s participation in the work force. The Gender Inequality Index is designed to reveal the extent to which national achievements in these aspects of human development are eroded by gender inequality, and to provide empirical foundations for policy analysis and advocacy efforts. How is the GII calculated, and what are its main findings in terms of national and regional patterns of inequality? There is no country with perfect gender equality – hence all countries suffer some loss in their HDI achievement when gender inequality is taken into account, through use of the GII metric. The Gender Inequality Index is similar in method to the Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) – see Technical Note 3 for details. It can be interpreted as a percentage loss to potential human development due to shortfalls in the dimensions included. Since the Gender Inequality Index includes different dimensions than the HDI, it cannot be interpreted as a loss in HDI itself. -

Human Development Index (HDI)

Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene Briefing note for countries on the 2020 Human Development Report Chile Introduction This year marks the 30th Anniversary of the first Human Development Report and of the introduction of the Human Development Index (HDI). The HDI was published to steer discussions about development progress away from GPD towards a measure that genuinely “counts” for people’s lives. Introduced by the Human Development Report Office (HDRO) thirty years ago to provide a simple measure of human progress – built around people’s freedoms to live the lives they want to - the HDI has gained popularity with its simple yet comprehensive formula that assesses a population’s average longevity, education, and income. Over the years, however, there has been a growing interest in providing a more comprehensive set of measurements that capture other critical dimensions of human development. To respond to this call, new measures of aspects of human development were introduced to complement the HDI and capture some of the “missing dimensions” of development such as poverty, inequality and gender gaps. Since 2010, HDRO has published the Inequality-adjusted HDI, which adjusts a nation’s HDI value for inequality within each of its components (life expectancy, education and income) and the Multidimensional Poverty Index that measures people’s deprivations directly. Similarly, HDRO’s efforts to measure gender inequalities began in the 1995 Human Development Report on gender, and recent reports have included two indices on gender, one accounting for differences between men and women in the HDI dimensions, the other a composite of inequalities in empowerment and well-being. -

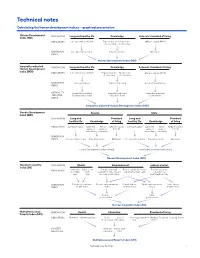

Technical Notes

Technical notes Calculating the human development indices—graphical presentation Human Development DIMENSIONS Long and healthy life Knowledge A decent standard of living Index (HDI) INDICATORS Life expectancy at birth Expected years Mean years GNI per capita (PPP $) of schooling of schooling DIMENSION Life expectancy index Education index GNI index INDEX Human Development Index (HDI) Inequality-adjusted DIMENSIONS Long and healthy life Knowledge A decent standard of living Human Development Index (IHDI) INDICATORS Life expectancy at birth Expected years Mean years GNI per capita (PPP $) of schooling of schooling DIMENSION Life expectancy Years of schooling Income/consumption INDEX INEQUALITY- Inequality-adjusted Inequality-adjusted Inequality-adjusted ADJUSTED life expectancy index education index income index INDEX Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) Gender Development Female Male Index (GDI) DIMENSIONS Long and Standard Long and Standard healthy life Knowledge of living healthy life Knowledge of living INDICATORS Life expectancy Expected Mean GNI per capita Life expectancy Expected Mean GNI per capita years of years of (PPP $) years of years of (PPP $) schooling schooling schooling schooling DIMENSION INDEX Life expectancy index Education index GNI index Life expectancy index Education index GNI index Human Development Index (female) Human Development Index (male) Gender Development Index (GDI) Gender Inequality DIMENSIONS Health Empowerment Labour market Index (GII) INDICATORS Maternal Adolescent Female and male Female -

Inequalities in Human Development in the 21St Century

Human Development Report 2019 Inequalities in Human Development in the 21st Century Briefing note for countries on the 2019 Human Development Report Egypt Introduction The main premise of the human development approach is that expanding peoples’ freedoms is both the main aim of, and the principal means for sustainable development. If inequalities in human development persist and grow, the aspirations of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development will remain unfulfilled. But there are no pre-ordained paths. Gaps are narrowing in key dimensions of human development, while others are only now emerging. Policy choices determine inequality outcomes – as they do the evolution and impact of climate change or the direction of technology, both of which will shape inequalities over the next few decades. The future of inequalities in human development in the 21st century is, thus, in our hands. But we cannot be complacent. The climate crisis shows that the price of inaction compounds over time as it feeds further inequality, which, in turn, makes action more difficult. We are approaching a precipice beyond which it will be difficult to recover. While we do have a choice, we must exercise it now. Inequalities in human development hurt societies and weaken social cohesion and people’s trust in government, institutions and each other. They hurt economies, wastefully preventing people from reaching their full potential at work and in life. They make it harder for political decisions to reflect the aspirations of the whole society and to protect our planet, as the few pulling ahead flex their power to shape decisions primarily in their interests. -

Comparing Global Gender Inequality Indices: Where Is Trade?

DECEMB ER 2019 UNCTAD Research Paper No. 39 UNCTAD/SER.RP/2019/11 Nour Barnat Division on Comparing Global Gender Globalization and Development Strategies, UNCTAD Inequality Indices: Where is [email protected] Trade? Steve MacFeely Abstract Division on Globalization and This paper presents a comparative study of selected global Development gender inequality indices: The Global Gender Gap Index (GGI); Strategies, UNCTAD the Gender Inequality Index (GII); and the Social Institutions and [email protected] Gender Index (SIGI). A Principal Component Analysis approach is used to identify the most important factors or dimensions, such as, health, social conditions and education, economic and Anu Peltola labour participation and political empowerment that impact on gender and drive gender inequality. These factors are Division on Globalization and compared with the Sustainable Development Goal targets to Development assess how well they align. The findings show that while Strategies, UNCTAD economic participation and empowerment are significant [email protected] factors of gender equality, they are not fully incorporated into gender equality indices. In this context, the paper also discusses the absence of international trade, a key driver of economic development, from the gender equality measures and makes some tentative recommendations for how this lacuna might be addressed. Key words: Principal Component Analysis, Composite Indicators, 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, SDGs, Trade. © 2019 United Nations 2 UNCTAD Research Paper -

The Impact of Digital Feminist Activism by Cassie

#TrendingFeminism: The Impact of Digital Feminist Activism by Cassie Clark B.A. in English and Theatre, May 2007, St. Olaf College A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 17, 2015 Thesis directed by Todd Ramlow Adjunct Professor of Women’s Studies This work is dedicated to my grandfather, who, upon being told that I was planning to attend graduate school, responded, “Good, you should have more education than your father.” ii The author wishes to acknowledge Dr. Todd Ramlow for his expertise, knowledge, and encouragement. She also wishes to acknowledge Dr. Alexander Dent for his invaluable guidance regarding the performance of media and digital technologies. iii Abstract of Thesis #TrendingFeminism: The Impact of Digital Feminist Activism As the use of online platforms such as social networking sites, also known as social media, and blogs grew in popularity, feminists began to embrace digital media as a significant space for activism. Digital feminist activism is a new iteration of feminist activism, offering new tools and tactics for feminists to utilize to spread awareness, disseminate information, and mobilize constituents. In this paper I examine the intent, usefulness, and potential impact of digital feminist activism in the United States by analyzing key examples of social movements conducted via digital media. These analyses not only provide useful examples of a variety of digital feminist efforts, they also highlight strengths and weaknesses in each campaign with the aim of improving the impact of future digital feminist campaigns. -

Global Gender Gap Report Global Gender Gap Report

cover.final 1/18/10 9:55 PM Page 1 The The Global Gender Gap Report Global Gender Gap Report The World Economic Forum is an independent interna- Ricardo Hausmann, Harvard University 2009 tional organization committed to improving the state of Laura D. Tyson, University of California, Berkeley the world by engaging leaders in partnerships to shape Saadia Zahidi, World Economic Forum global, regional and industry agendas. Incorporated as a foundation in 1971, and based in Geneva, Switzerland, 2009 the World Economic Forum is impartial and not-for-profit; it is tied to no political, partisan or national interests. www.weforum.org part1.correx 1/18/10 11:50 AM Page i World Economic Forum Geneva, Switzerland 2009 The Global Gender Gap Report 2009 Ricardo Hausmann, Harvard University Laura D. Tyson, University of California, Berkeley Saadia Zahidi, World Economic Forum part1.correx 1/18/10 11:50 AM Page ii The Global Gender Gap Report 2009 is World Economic Forum published by the World Economic Forum. 91-93 route de la Capite The Gender Gap Index 2009 is the result of CH-1223 Cologny/Geneva collaboration with faculty at Harvard University Switzerland and University of California, Berkeley. Tel.: +41 (0)22 869 1212 Fax: +41 (0)22 786 2744 E-mail: [email protected] AT THE WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM www.weforum.org Professor Klaus Schwab © 2009 World Economic Forum Founder and Executive Chairman All rights reserved. Saadia Zahidi Director and Head of Constituents No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, Damaris Papoutsakis including photocopying and recording, or by Project Associate for Women Leaders & Gender any information storage and retrieval system. -

Standard 5: Scholarship: Research, Creative and Professional Activity

ACEJMC Standard 5 5-1 STANDARD 5: SCHOLARSHIP: RESEARCH, CREATIVE AND PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITY Dr. Isaksen (top) and Dr. Fowkes (bottom) recipients of the University’s top teaching and research awards respectively. Shown with President Qubein (l) and Provost Carroll (R) ACEJMC Standard 5 5-2 STANDARD 5: SCHOLARSHIP: RESEARCH, CREATIVE AND PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITY Highlights The Nido R. Qubein School of Communication has active faculty that conducts peer-reviewed and professional research and produces national quality media. The unit has an active sabbatical program, which has benefited two School faculty to date. The unit also provides robust annual funding for professional development—currently at $2,000 per year per faculty member. ACEJMC Standard 5 5-3 STANDARD 5—SCHOLARSHIP: RESEARCH, CREATIVE AND PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITY 1. Describe the institution’s mission regarding scholarship by faculty and the unit’s policies for achieving that mission. Faculty at High Point University are expected to develop robust academic and/or creative work agendas. As noted in the faculty handbook: Effective faculty members are actively engaged with their academic fields as scholars and as confident exponents and interpreters of their disciplines. They are so engaged because of their abiding interest in and passion for the practice of the discipline (. .). Faculty scholarship can help shape the academic environment at the University. Faculty scholarship creates an intellectual atmosphere at the University that sets before faculty members and students alike a model for a community that can inspire and motivate students and faculty to higher levels of personal achievement. Faculty scholarship brings recognition not just to the person but also to the community that has formed itself to support such activity. -

Gender Equality and Media Freedom in Azerbaijan" Project

"Gender equality and media freedom in Azerbaijan" Project CURRICULUM on "GENDER EQUALITY AND MEDIA FREEDOM" a course for Journalism faculties This document has been developed within the Council of Europe Project “Gender equality and media freedom in Azerbaijan”. The views expressed herein can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of the Council of Europe. @ Council of Europe, 2019 Prepared by: Aynur Bashirli, Ph.D. on Political Sciences, media expert Sevinj Aliyeva, Ph.D. on Philology, Baku State University Gulnaz Alesgerova, Ph.D. on Law, Baku State University Shafag Mehraliyeva, ADA University, School of Public and International Affairs, faculty member Alasgar Mammadli, expert on media law Reviewed by: Dr. Krisztina Rozgonyi, University of Vienna This curriculum is recommended for printing by the Academic Council of the School of Journalism of Baku State University (decision dated 14 February 2019, Protocol # 4). 1. Subject and objectives of the course: Gender and women affairs (problems), gender stereotypes and media as the subject of the course. The main objective of the course “Gender equality and media freedom”: Provide students with an insight into fundamental issues of gender equality and media freedom; and promote an approach from a gender perspective towards the media freedom, including pluralism, independence and safety; Familiarize students with the European standards of human rights, national legislation and practice in this field; Introduce the current situation of gender equality in terms of media freedom concept in Azerbaijan; Develop students’ ability of critical thinking to analyse social gender stereotypes and standards, sexist approaches in the society and in the media.