Places for Races: the White Supremacist Movement Imagines U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paul Craig Roberts

THE WEST’S DARKEST HOUR THE SITE FOR PRIESTS OF THE 14 WORDS Oasis in the middle of the desert Concerned about the events of this month, I began my work this morning by visiting the main sites of white nationalism. I felt completely dehydrated when I ran into the usual: these guys are bourgeois to the core! Not even with this transitional government that will hand over all power to an anti- white mulatta after the senile man doesn’t run for a second term, do they speak like Aryans. Desperate, in a search engine I typed the words ‘revolution’ and the name of the retired revolutionary writer ‘Michael O’Meara’. I ‘Almost as depressing as came across an oasis in the desert! I am referring to the article I the thought of our people’s added today, ‘Against white reformists’, although I had already extinction is that of the quoted some of those passages almost seven years ago. The first white opposition to it’. — sentence of the article was the water that brought me back to life Michael O’Meara after wandering in the wasteland of white nationalism: ‘Almost as depressing as the thought of our people’s extinction is that of the For the donation button, white opposition to it’. But O’Meara is not perfect. He said: see the bottom of this page. The Modern West, unlike its Medieval and Ancient counterparts, has shed all sense of tradition, transcendence, and fidelity. White nationalists ignore that so-called ‘human Although he wrote it in 2007, this shows that he was unaware of the real history of Christianity (‘unlike its Medieval and Ancient rights’ are, in the final counterparts…’). -

Quand L'eitreme Droite Se Met En Culture

QUAND L'EITREME DROITE SE MET EN CULTURE Allemagne Afrique du Sud Angleterre qu'est-ce que REFLEX : EFLEX est une association qui a tionnement. ses idees et ses pra- pour objectif de lutter contre le tiques. nous etions tres proches. Rracisme, le fascisme, les idees et Demain, nous continuerons ce travail pratiques securitaires et xenophobes. en l'elargissant. Dans ce cadre, nous elargissons nos etre membre de REFLEX activites a toutes les,mesures de Notre association ne peut vivre que REFLEXes est edite par le repression prises par I' Etat francais : par ses adherents. En effet, nous ne prison, discrimination vis-a-vis des beneficions d'aucune subvention et populations etrangeres, contre les nous n'en demandons pas. Appartenir reseau REFlEX peuples en lutte (basque, corse, a REFLEX, c'est etre d'accord avec ses kanak, etc.). Notre lutte n'est pas sim- objectifs et participer a la propaga- directeur de publication plement hexagonale et nous accor- tion des idees et des actions qui sont dons une grande place a 1' Europe. contenues dans le journal et dans Notre choix de combattre sur ces ter- l'association. C'est agir dans son quo- 8.Delmotte rains ne signifie pas que nous nous tidien, a l'interieur d'associations, de desinteressons des autres questions collectifs, individuellement dans les depot legal a parution qui se posent dans notre societe : lieux que nous frequenlons. Tiers-monde, environnement social, C'est participer aux campagnes de 9339 economique... Mais nous savons que solidarite, aux actions, aux manifesta- ICCN 0764 - nous ne pouvons repondre et agir sur tions, etc. -

Identitarian Movement

Identitarian movement The identitarian movement (otherwise known as Identitarianism) is a European and North American[2][3][4][5] white nationalist[5][6][7] movement originating in France. The identitarians began as a youth movement deriving from the French Nouvelle Droite (New Right) Génération Identitaire and the anti-Zionist and National Bolshevik Unité Radicale. Although initially the youth wing of the anti- immigration and nativist Bloc Identitaire, it has taken on its own identity and is largely classified as a separate entity altogether.[8] The movement is a part of the counter-jihad movement,[9] with many in it believing in the white genocide conspiracy theory.[10][11] It also supports the concept of a "Europe of 100 flags".[12] The movement has also been described as being a part of the global alt-right.[13][14][15] Lambda, the symbol of the Identitarian movement; intended to commemorate the Battle of Thermopylae[1] Contents Geography In Europe In North America Links to violence and neo-Nazism References Further reading External links Geography In Europe The main Identitarian youth movement is Génération identitaire in France, a youth wing of the Bloc identitaire party. In Sweden, identitarianism has been promoted by a now inactive organisation Nordiska förbundet which initiated the online encyclopedia Metapedia.[16] It then mobilised a number of "independent activist groups" similar to their French counterparts, among them Reaktion Östergötland and Identitet Väst, who performed a number of political actions, marked by a certain -

Pursuit of an Ethnostate: Political Culture and Violence 22 in the Pacific Northwest Joseph Stabile

GEORGETOWN SECURITY STUDIES REVIEW Published by the Center for Security Studies at Georgetown University’s Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service Editorial Board Rebekah H. Kennel, Editor-in-Chief Samuel Seitz, Deputy Editor Stephanie Harris, Associate Editor for Africa Kelley Shaw, Associate Editor for the Americas Brigitta Schuchert, Associate Editor for Indo-Pacific Daniel Cebul, Associate Editor for Europe Simone Bak, Associate Editor for the Middle East Eric Altamura, Associate Editor for National Security & the Military Timothy Cook, Associate Editor for South and Central Asia Max Freeman, Associate Editor for Technology & Cyber Security Stan Sundel, Associate Editor for Terrorism & Counterterrorism The Georgetown Security Studies Review is the official academic journal of Georgetown University’s Security Studies Program. Founded in 2012, the GSSR has also served as the official publication of the Center for Security Studies and publishes regular columns in its online Forum and occasional special edition reports. Access the Georgetown Security Studies Review online at http://gssr.georgetown.edu Connect on Facebook at http://www.facebook.com/GeorgetownUniversityGSSR Follow the Georgetown Security Studies Review on Twitter at ‘@gssreview’ Contact the Editor-in-Chief at [email protected] Table of Contents Understanding Turkey’s National Security Priorities in Syria 6 Patrick Hoover Pursuit of an Ethnostate: Political Culture and Violence 22 in the Pacific Northwest Joseph Stabile Learn to Live With It: The Necessary, But Insufficient, -

Testimony of Lecia Brooks Chief of Staff, Southern Poverty Law Center Before the Armed Services Committee United States House of Representatives

Testimony of Lecia Brooks Chief of Staff, Southern Poverty Law Center before the Armed Services Committee United States House of Representatives Extremism in the Armed Forces March 24, 2021 My name is Lecia Brooks. I am chief of staff of the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC). Thank you for the opportunity to present testimony on extremism in the U.S. Armed Forces and what we can do to address this challenge. Now in our 50th year, the SPLC is a catalyst for racial justice in the South and beyond, working in partnership with communities to dismantle white supremacy, strengthen intersectional movements, and advance the human rights of all people. SPLC lawyers have worked to shut down some of the nation’s most violent white supremacist groups by winning crushing, multimillion-dollar jury verdicts on behalf of their victims. We have helped dismantle vestiges of Jim Crow, reformed juvenile justice practices, shattered barriers to equality for women, children, the LGBTQ+ community, and the disabled, and worked to protect low-wage immigrant workers from exploitation. The SPLC began tracking white supremacist activity in the 1980s, during a resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan and other organized extremist hate groups. Today, the SPLC is the premier U.S. nonprofit organization monitoring the activities of domestic hate groups and other extremists. Each year since 1990, we have conducted a census of hate groups operating across America, a list that is used extensively by journalists, law enforcement agencies, and scholars, among others. The SPLC Action Fund is dedicated to fighting for racial justice alongside impacted communities in pursuit of equity and opportunity for all. -

The FBI, COINTELPRO-WHITE HATE, and the Nazification of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1970S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Biodiversity Informatics From White Supremacy to White Power 49 From White Supremacy to White Power: The FBI, COINTELPRO-WHITE HATE, and the Nazification of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1970s John Drabble In the 1960s, the leader of the largest Ku Klux Klan organization in the United States presumed that the Federal Bureau of Investigation was a meritorious ally engaged in a common battle against Communist subversion.1 By 1971 however, United Klans of America (UKA) Imperial Wizard Robert Shelton had concluded that the FBI was “no longer the respected and honorable arm of justice that it once appeared to be.”2 A year later the UKA’s Fiery Cross published an editorial written by former American Nazi Party official William Pierce, who declared that the federal government had “been transformed [into] a corrupt, unnatural and degenerate monstrosity,” and exhorted Klansmen to launch a bloody revolution against it.3 Twenty years before overtly repressive FBI tactics at Ruby Ridge, Idaho, and Waco, Texas, convinced thousands of Americans to join the militia movement, Klansmen had already begun to condemn the FBI and espouse revo- lution. This article argues that during the 1970s, Klan organizers transformed a reactionary counter-movement that had failed to preserve white supremacy by terrorizing civil rights organizers and black citizens, into a revolutionary white power movement that inculpated Jews and the federal government.4 It describes how these organizers -

Instauration®

Instauration® Ponderable Quote of the Year Will humankind continue to evolve? The present answer must be "no." Cultural evolution has buffered us against biological pressures that weeded out the feeble, slow, or stupid. Now, power tools, computers, clothes, spectacles, and modern medicinedevaluethe old inherited advantages of powerful physique, intelli gence, pigmentation, vistJaL ·acuity and resistance to diseases like malaria. Societies hold high percentages of physically weak or ill-proportioned people, and people with poor eyesight, or skin color and disease resista.nce unrelated to the climates where they live. Some individuals who would have died in infancy a century ago survive to breed, handing on genetic fau Its to futu re generations. Migration, too, has helped halt human evolution. No group lives isolated long enough to evolve into a new species as happened in the Pleistocene. And racial differences will decline with increased inter breeding of peoples from Europe, Africa, the Amer icas, India and China. David Lanlbert, The Cambridge Guide to Prehistoric Man Cambridge University Press o The Pope is the head of the Roman Catholic Church, but who is the head Jewl If you ever find out, please let me know. 522 In keeping with Instauration's policy of anonym o Over here, only the intellectuals compre o I'm not sure that Bush's well-tailored back ity, most communicants will be identified by the hend who controls the u.s. media and politics. ground adds up to a return to Majorityism. The first three digits of their zip codes. The masses are unable to understand why the Bush brand of Republicanism (the "progres u.s. -

An Inquiry Into Contemporary Australian Extreme Right

THE OTHER RADICALISM: AN INQUIRY INTO CONTEMPORARY AUSTRALIAN EXTREME RIGHT IDEOLOGY, POLITICS AND ORGANIZATION 1975-1995 JAMES SALEAM A Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor Of Philosophy Department Of Government And Public Administration University of Sydney Australia December 1999 INTRODUCTION Nothing, except being understood by intelligent people, gives greater pleasure, than being misunderstood by blunderheads. Georges Sorel. _______________________ This Thesis was conceived under singular circumstances. The author was in custody, convicted of offences arising from a 1989 shotgun attack upon the home of Eddie Funde, Representative to Australia of the African National Congress. On October 6 1994, I appeared for Sentence on another charge in the District Court at Parramatta. I had been convicted of participation in an unsuccessful attempt to damage a vehicle belonging to a neo-nazi informer. My Thesis -proposal was tendered as evidence of my prospects for rehabilitation and I was cross-examined about that document. The Judge (whose Sentence was inconsequential) said: … Mr Saleam said in evidence that his doctorate [sic] of philosophy will engage his attention for the foreseeable future; that he has no intention of using these exertions to incite violence.1 I pondered how it was possible to use a Thesis to incite violence. This exercise in courtroom dialectics suggested that my thoughts, a product of my experiences in right-wing politics, were considered acts of subversion. I concluded that the Extreme Right was ‘The Other Radicalism’, understood by State agents as odorous as yesteryear’s Communist Party. My interest in Extreme Right politics derived from a quarter-century involvement therein, at different levels of participation. -

Birth of a Nation: Harold Covington's

THE BIRTH OF A NATION The Hill of the Ravens A Distant Thunder H. A. Covington H. A. Covington Lincoln, Nebr.: 1stBooks Library, Bloomington, Ind.: Authorhouse, 2003 2004 A Mighty Fortress The Brigade H. A. Covington H. A. Covington Bloomington, Ind.: Authorhouse, Philadelphia: Xlibris, 2008 2005 Reviewed by Greg Johnson Every time a friend adds another weapon to his arsenal, he says “I hope to God I never have to use this.” But he keeps buying them, be- cause they may come in handy. I say the same thing every time I pick up a Harold Covington novel. But I keep reading them. They may come in handy some day. The four novels under review, collectively called the Northwest Quartet, tell the story of the creation of a sovereign white nationalist state, the Northwest American Republic, out of the territory of the United States sometime in the second or third decade of the twenty- first century—right around the corner. The NAR comprises the pre- sent US states of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho, plus parts of North- ern California, Montana, and Wyoming. These states secede from the United States through a bitter five-year guerilla war fought by the Northwest Volunteer Army. The NVA is an armed political party. Its ideology owes much to German National Socialism, but its tactics are modeled on the Irish Republican Army and the mafia, as well as Mus- lim organizations like Hamas in Palestine, Hezbollah in Lebanon, and the insurgents who have stymied the United States in Iraq and Af- ghanistan. These novels are war stories, and frankly that makes me squeam- ish. -

The Hate Directory

The Hate Directory Compiled by Raymond A. Franklin Forward corrections and additions to: Raymond A. Franklin P.O. Box 121 Woodstock, MD 21163-0121 [email protected] Hate Groups on the Internet: Publication date: Web Sites (WWW) September 1, 2006 File Archives (FTP) Racist Weblogs (Blogs) and Blog Services Release 10.2 Mailing Lists (LISTSERV) Newsgroups (USENET) Internet Relay Chat (IRC) Yahoo Clubs, Yahoo Groups and MSN Groups Racist Web Rings Racist Games Available on the Internet Racialist Friendly Web Hosting Services Copyright 1996-2006 Directory of Groups Combatting Hate on the Net All Rights Reserved PREFACE The Hate Directory is maintained and presented as an aid in identifying and tracking the proliferation of hate oriented use of the Internet and other new electronic media. The Directory is an historical document as well as a current reference, and includes current sites as well as those no longer in operation. CRITERION STATEMENT Included are Internet sites of individuals and groups that, in the opinion of the author, advocate violence against, separation from, defamation of, deception about, or hostility toward others based upon race, religion, ethnicity, gender or sexual orientation. ELECTRONIC EDITION An interactive version of The Hate Directory is available on the World Wide Web at www.hatedirectory.com. COMMENTS Your assistance is appreciated. Please forward information regarding additional sites, errors and changes to [email protected] or the postal address above. Information regarding the value of this -

A Glossary of Northwest Acronyms and Terms

A Glossary of Northwest Acronyms and Terms A Mighty Fortress Is Our God - Christian hymn originally written in German by Martin Luther. The national anthem of the Northwest American Republic. ASU - Active Service Unit. The basic building block of the NVA paramilitary structure. Generally speaking, an active service unit was any team or affinity group of Northwest Volunteers engaged in armed struggle against the United States government. The largest active service units during the War of Independence were the Flying Columns (q.v.) that moved across the countryside in open insurrection. These could sometimes number as many as 75 or even 100 men. More usual was the urban team or crew ranging from four or five to no more than a dozen Volunteers. After a unit grew larger than seven or eight people, the logistics of movement and supply and also the risk of betrayal reached unacceptably high levels, and the cell would divide in two with each half going its separate way. Command and coordination between the units was often tenuous at best. The success and survival of an active service unit was often a matter of the old Viking adage: “Luck often enough will save a man. if his courage hold.” Aztlan - A semi-autonomous province of Mexico consisting of the old American states of southern and western Texas. Arizona. New Mexico. Utah, parts of Colorado, and southern California below a line roughly parallel with the Mountain Gate border post. BATF - Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms division of the United States Treasury Department. Used by the government in Washington D. -

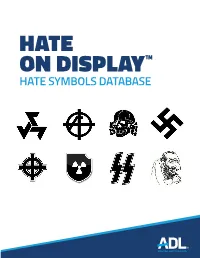

Hate Symbols Database

HATE ON DISPLAY™ HATE SYMBOLS DATABASE 1 HATE ON DISPLAY This database provides an overview of many of the symbols most frequently used by a variety of white supremacist groups and movements, as well as some other types of hate groups. You can find the full listings at adl.org/hate-symbols INTRODUCTION TO THE HATE ON DISPLAY HATE SYMBOLS DATABASE ADL is a leading anti-hate organization that was founded in 1913 in response to an escalating climate of anti-Semitism and bigotry. Today, ADL is the first call when acts of anti-Semitism occur and continues to fight all forms of hate. A global leader in exposing extremism, delivering anti-bias education and fighting hate online, ADL’s ultimate goal is a world in which no group or individual suffers from bias, discrimination or hate. ADL’s Center on Extremism debuted its Hate on Display hate symbols database in 2000, establishing the database as the first and foremost resource on the internet for symbols, codes, and memes used by white supremacists and other types of haters. Over the past two decades, Hate on Display has regularly been updated with new symbols and images as they have come into common use by extremists, as well as new functions to make it more useful and convenient for users. Although the database contains many examples of online usage and shared graphics, another feature that makes it unique is its emphasis on real world examples of hate symbols—showing them as extremists actually use them: on signs and clothing, graffiti and jewelry, and even on their own bodies as tattoos and brands.