A Guide to Online Radical-Right Symbols, Slogans and Slurs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2018 Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany William Peter Fitz University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Fitz, William Peter, "Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany" (2018). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 275. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/275 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REACTIONARY POSTMODERNISM? NEOLIBERALISM, MULTICULTURALISM, THE INTERNET, AND THE IDEOLOGY OF THE NEW FAR RIGHT IN GERMANY A Thesis Presented by William Peter Fitz to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In European Studies with Honors December 2018 Defense Date: December 4th, 2018 Thesis Committee: Alan E. Steinweis, Ph.D., Advisor Susanna Schrafstetter, Ph.D., Chairperson Adriana Borra, M.A. Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One: Neoliberalism and Xenophobia 17 Chapter Two: Multiculturalism and Cultural Identity 52 Chapter Three: The Philosophy of the New Right 84 Chapter Four: The Internet and Meme Warfare 116 Conclusion 149 Bibliography 166 1 “Perhaps one will view the rise of the Alternative for Germany in the foreseeable future as inevitable, as a portent for major changes, one that is as necessary as it was predictable. -

Ing Items Have Been Registered

ACCEPTANCES Page 1 of 37 June 2017 LoAR THE FOLLOWING ITEMS HAVE BEEN REGISTERED: ÆTHELMEARC Alrekr Bergsson. Device. Per saltire gules and sable, in pale two wolf’s heads erased and in fess two sheaves of arrows Or. Brahen Lapidario. Name and device. Argent, a lozenge gules between six French-cut gemstones in profile, two, two and two azure, a base gules. The ’French-cut’ is a variant form of the table cut, a precursor to the modern brilliant cut. It dates to the early 15th Century, according to "Diamond Cuts in Historic Jewelry" by Herbert Tillander. There is a step from period practice for gemstones depicted in profile. Hrólfr á Fjárfelli. Device. Argent estencely sable, an ash tree proper issuant from a mountain sable. Isabel Johnston. Device. Per saltire sable and purpure, a saltire argent and overall a winged spur leathered Or. Lisabetta Rossi. Name and device. Per fess vert and chevronelly vert and Or, on a fess Or three apples gules, in chief a bee Or. Nice early 15th century Florentine name! Símon á Fjárfelli. Device. Azure, a drakkar argent and a mountain Or, a chief argent. AN TIR Akornebir, Canton of. Badge for Populace. (Fieldless) A squirrel gules maintaining a stringless hunting horn argent garnished Or. An Tir, Kingdom of. Order name Order of Lions Mane. Submitted as Order of the Lion’s Mane, we found no evidence for a lion’s mane as an independent heraldic charge. We therefore changed the name to Order of _ Lions Mane to follow the pattern of Saint’s Name + Object of Veneration. -

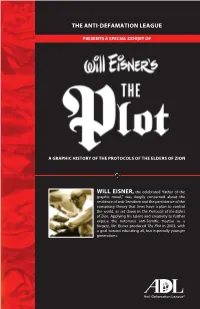

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion: a Hoax to Hate Introduction

THE ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE PRESENTS A SPECIAL EXHIBIT OF A GRAPHIC HISTORY OF THE PROTOCOLS OF THE ELDERS OF ZION WILL EISNER, the celebrated “father of the graphic novel,” was deeply concerned about the resilience of anti-Semitism and the persistence of the conspiracy theory that Jews have a plan to control the world, as set down in The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Applying his talent and creativity to further expose the notorious anti-Semitic treatise as a forgery, Mr. Eisner produced The Plot in 2003, with a goal toward educating all, but especially younger generations. A SPECIAL EXHIBIT PRESENTED BY THE ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE ADL is proud to present a special traveling exhibit telling the story of the infamous forgery, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, that has been used to justify anti-Semitism up to and including today. In 2005, Will Eisner’s graphic novel, The Plot: The Secret Story of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion was published, exposing the history of The Protocols and raising public awareness of anti-Semitism. Mr. Eisner, who died in 2005, did not live to see this highly effective exhibit, but his commitment and spirit shine through every panel of his work on display. This project made possible through the support of the Will Eisner Estate and W.W. Norton & Company Inc. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion: A Hoax to Hate Introduction It is a classic in the literature of hate. Believed by many to be the secret minutes of a Jewish council called together in the last years of the 19th century, it has been used by anti-Semites as proof that Jews are plotting to take over the world. -

The Global New Right and the Flemish Identitarian Movement Schild & Vrienden a Case Study

Paper The global New Right and the Flemish identitarian movement Schild & Vrienden A case study by Ico Maly© (Tilburg University) [email protected] December 2018 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/ The global New Right and the Flemish identitarian movement Schild & Vrienden. A case study. Ico Maly Abstract: This paper argues that nationalism, and nationalistic activism in particular are being globalized. At least certain fringes of radical nationalist activists are organized as ‘cellular systems’ connected and mobilize-able on a global scale giving birth to what I call ‘global nationalistic activism’. Given this change in nationalist activism, I claim that we should abandon all ‘methodological nationalism’. Methodological nationalism fails in arriving at a thorough understanding of the impact, scale and mobilization power (Tilly, 1974) of contemorary ‘national(istic)’ political activism. Even more, it inevitably will contribute to the naturalization or in emic terms the meta-political goals of global nationalist activists. The paradox is of course evident: global nationalism uses the scale- advantages, network effects and the benefits of cellular structures to fight for the (re)construction of the old 19th century vertebrate system par excellence: the (blood and soil) nation. Nevertheless, this, I will show, is an indisputable empirical reality: the many local nationalistic battles are more and more embedded in globally operating digital infrastructures mobilizing militants from all corners of the world for nationalist causes at home. Nationalist activism in the 21st century, so goes my argument, has important global dimensions which are easily repatriated for national use. -

Bulk Catalogue July 2017

BULK CATALOGUE JULY 2017 YOU ARE RECEIVING THIS CATALOGUE FOR BEING EITHER A BULK CUSTOMER OR FREQUENT REVIEWER OF OUR PUBLICATIONS. From the Editor ecently, I have had the pleasure and European genealogy and global destiny of R good fortune of editing two manu- our Faustian anti-globalist movement, and scripts that are particularly noteworthy. also owe a profound debt to the thought of These are Alexander Dugin’s The Rise of Martin Heidegger (as I do), that drew me the Fourth Political Theory, and the first to Arktos in the first place. volume of the long-awaited English trans- Although I am inundated with manu- lation of Alain de Benoist’s magnum opus, scripts to review (most of which I have View from the Right. Dugin’s book, which had to reject despite their relatively high is the second volume of his The Fourth quality), it has also been possible to find Political Theory, was fascinating to me the time to work on my own second book, insofar as he draws on the metaphysics of which is now nearing completion. It con- the Medieval Iranian philosopher, Shahab cerns the sociopolitical implications of al-din Suhrawardi in order to develop convergent advancements in technology his geopolitical concept of an ‘Oriental’ that fundamentally call into question hu- Eurasia that is a radiantly solar point of man existence and represent an apocalyp- orientation opposed to the twilight of the tic rupture in world history. If Prometheus Atlanticist world with its nihilist historical and Atlas was the intellectual equivalent trajectory. I also found it noteworthy that of an atomic bomb, this book is the death Benoist’s encyclopedic study of European star. -

Pepe the Frog

PEPE THE FROG: A Case Study of the Internet Meme and its Potential Subversive Power to Challenge Cultural Hegemonies by BEN PETTIS A THESIS Presented to the School of Journalism and Communication and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Spring 2018 An Abstract of the Thesis of Ben Pettis for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the School of Journalism and Communication to be taken Spring 2018 Title: Pepe the Frog: A Case Study of the Internet Meme and Its Potential Subversive Power to Challenge Cultural Hegemonies Approved: _______________________________________ Dr. Peter Alilunas This thesis examines Internet memes, a unique medium that has the capability to easily and seamlessly transfer ideologies between groups. It argues that these media can potentially enable subcultures to challenge, and possibly overthrow, hegemonic power structures that maintain the dominance of a mainstream culture. I trace the meme from its creation by Matt Furie in 2005 to its appearance in the 2016 US Presidential Election and examine how its meaning has changed throughout its history. I define the difference between a meme instance and the meme as a whole, and conclude that the meaning of the overall meme is formed by the sum of its numerous meme instances. This structure is unique to the medium of Internet memes and is what enables subcultures to use them to easily transfer ideologies in order to challenge the hegemony of dominant cultures. Dick Hebdige provides a model by which a dominant culture can reclaim the images and symbols used by a subculture through the process of commodification. -

The Radical Roots of the Alt-Right

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. The Radical Roots of the Alt-Right Josh Vandiver Ball State University Various source media, Political Extremism and Radicalism in the Twentieth Century EMPOWER™ RESEARCH The radical political movement known as the Alt-Right Revolution, and Evolian Traditionalism – for an is, without question, a twenty-first century American audience. phenomenon.1 As the hipster-esque ‘alt’ prefix 3. A refined and intensified gender politics, a suggests, the movement aspires to offer a youthful form of ‘ultra-masculinism.’ alternative to conservatism or the Establishment Right, a clean break and a fresh start for the new century and .2 the Millennial and ‘Z’ generations While the first has long been a feature of American political life (albeit a highly marginal one), and the second has been paralleled elsewhere on the Unlike earlier radical right movements, the Alt-Right transnational right, together the three make for an operates natively within the political medium of late unusual fusion. modernity – cyberspace – because it emerged within that medium and has been continuously shaped by its ongoing development. This operational innovation will Seminal Alt-Right figures, such as Andrew Anglin,4 continue to have far-reaching and unpredictable Richard Spencer,5 and Greg Johnson,6 have been active effects, but researchers should take care to precisely for less than a decade. While none has continuously delineate the Alt-Right’s broader uniqueness. designated the movement as ‘Alt-Right’ (including Investigating the Alt-Right’s incipient ideology – the Spencer, who coined the term), each has consistently ferment of political discourses, images, and ideas with returned to it as demarcating the ideological territory which it seeks to define itself – one finds numerous they share. -

The Rhinolophus Affinis Bat ACE2 and Multiple Animal Orthologs Are Functional 2 Receptors for Bat Coronavirus Ratg13 and SARS-Cov-2 3

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.16.385849; this version posted November 17, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. 1 The Rhinolophus affinis bat ACE2 and multiple animal orthologs are functional 2 receptors for bat coronavirus RaTG13 and SARS-CoV-2 3 4 Pei Li1#, Ruixuan Guo1#, Yan Liu1#, Yintgtao Zhang2#, Jiaxin Hu1, Xiuyuan Ou1, Dan 5 Mi1, Ting Chen1, Zhixia Mu1, Yelin Han1, Zhewei Cui1, Leiliang Zhang3, Xinquan 6 Wang4, Zhiqiang Wu1*, Jianwei Wang1*, Qi Jin1*,, Zhaohui Qian1* 7 NHC Key Laboratory of Systems Biology of Pathogens, Institute of Pathogen 8 Biology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College1, 9 Beijing, 100176, China; School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Peking University2, 10 Beijing, China; .Institute of Basic Medicine3, Shandong First Medical University & 11 Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences, Jinan 250062, Shandong, China; The 12 Ministry of Education Key Laboratory of Protein Science, Beijing Advanced 13 Innovation Center for Structural Biology, Beijing Frontier Research Center for 14 Biological Structure, Collaborative Innovation Center for Biotherapy, School of Life 15 Sciences, Tsinghua University4, Beijing, China; 16 17 Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, bat coronavirus RaTG13, spike protein, Rhinolophus affinis 18 bat ACE2, host susceptibility, coronavirus entry 19 20 #These authors contributed equally to this work. 21 *To whom correspondence should be addressed: [email protected], 22 [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 23 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.16.385849; this version posted November 17, 2020. -

1 U.S. White Supremacy Groups Key Points

U.S. White Supremacy Groups Key Points: • Some modern white supremacist groups, such as The Base, Hammerskin Nation, and Atomwaffen Division, subscribe to a National Socialist (neo-Nazi) ideology. These groups generally make no effort to hide their overt racist belief that the white race is superior to others. • Other modern white supremacist groups, however, propagate their radical stances under the guise of white ethno-nationalism, which seeks to highlight the distinctiveness––rather than the superiority––of the white identity. Such groups, which include the League of the South and Identity Evropa, usually claim that white identity is under threat from minorities or immigrants that seek to replace its culture, and seek to promote white ethno- nationalism as a legitimate ideology that belongs in mainstream political spheres. • Most modern white supremacist groups eschew violent tactics in favor of using demonstrations and propaganda to sway public opinion and portray their ideologies as legitimate. However, their racial elitist ideologies have nonetheless spurred affiliated individuals to become involved in violent altercations. • White supremacist groups often target youth for recruitment through propaganda campaigns on university campuses and social media platforms. White supremacists have long utilized Internet forums and websites to connect, organize, and propagate their extremist messages. Executive Summary Since the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) first formed in 1865, white supremacist groups in the United States have propagated racism, hatred, and violence. Individuals belonging to these groups have been charged with a range of crimes, including civil rights violations, racketeering, solicitation to commit crimes of violence, firearms and explosives violations, and witness tampering.1 Nonetheless, white supremacist groups––and their extremist ideologies––persist in the United States today. -

Azov Phenomenon How Ukrai

INFORMATION GROUP ON CRIMES AGAINST THE PERSON (IGCP) INFORMATION GROUP ON CRIMES AGAINST THE PERSON (IGCP) Azov Phenomenon How Ukrainian Neo-Nazis Became Infl uential Political Force “IGCP Reports” (published since 2016) Head of the Project A.R. Dyukov. Issue 3. Editor M.A. Vilkov. Maltsev V. Azov Phenomenon How Ukrainian Neo-Nazis became Influential Political Force / Information Group on Crimes against the Person (IGCP). M.: “Istoricheskaya pamyat” Foundation, 2017. — 98 pages. There were the days when participants of right-wing and neo-Nazi groups in the Ukraine were marginal ones, being expelled to the edge of political and social life. Everything changed in 2014, during the so-called “Revolution of Dignity”. Ukrainian neo-Nazis gained money and weapon, they were given official status as Army, Police and Special Forces units, they got representatives in the Parliament. The history of “Azov” — notorious neo- Nazi detachment of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Ukraine — became an image of such transformation. “Azov” offsprings hold leading offices in Ukrainian Police, raise the youth in neo-Nazi ideology encirclement, effectively expand their representation on the Ukrainian political field and getting ready for the struggle for power. This report is devoted to the process of Ukrainian nationalists becoming influential political power. IGCP, 2017. Contents Preface ............................................................................7 Chapter 1. Street Militants...............................................11 Social-National Party of Ukraine .................................... 13 The Social-National Assembly ........................................ 25 Chapter 2. Neo-Nazis Get Armed ..................................... 41 Chapter 3: Forced March to Power ..................................69 Preface “Any man who has once acclaimed violence as his METHOD must inexorably choose false- hood as his PRINCIPLE.” A.I. -

Political Trends & Dynamics

Briefing Political Trends & Dynamics The Far Right in the EU and the Western Balkans Volume 3 | 2020 POLITICAL TRENDS & DYNAMICS IN SOUTHEAST EUROPE A FES DIALOGUE SOUTHEAST EUROPE PROJECT Peace and stability initiatives represent a decades-long cornerstone of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung’s work in southeastern Europe. Recent events have only reaffirmed the centrality of Southeast European stability within the broader continental security paradigm. Both de- mocratization and socio-economic justice are intrinsic aspects of a larger progressive peace policy in the region, but so too are consistent threat assessments and efforts to prevent conflict before it erupts. Dialogue SOE aims to broaden the discourse on peace and stability in southeastern Europe and to counter the securitization of prevalent narratives by providing regular analysis that involves a comprehensive understanding of human security, including structural sources of conflict. The briefings cover fourteen countries in southeastern Europe: the seven post-Yugoslav countries and Albania, Greece, Turkey, Cyprus, Bulgaria, Romania, and Moldova. PREVIOUSLY PUBLISHED • Civic Mobilizations • The Digital Frontier in • The European Project in the Western in Southeast Europe Southeast Europe Balkans: Crisis and Transition February / March 2017 February / March 2018 Volume 2/2019 • Regional Cooperation in • Religion and Secularism • Chinese Soft Power the Western Balkans in Southeast Europe in Southeast Europe April / Mai 2017 April / May 2018 Volume 3/2019 • NATO in Southeast Europe -

FUNDING HATE How White Supremacists Raise Their Money

How White Supremacists FUNDING HATE Raise Their Money 1 RESPONDING TO HATE FUNDING HATE INTRODUCTION 1 SELF-FUNDING 2 ORGANIZATIONAL FUNDING 3 CRIMINAL ACTIVITY 9 THE NEW KID ON THE BLOCK: CROWDFUNDING 10 BITCOIN AND CRYPTOCURRENCIES 11 THE FUTURE OF WHITE SUPREMACIST FUNDING 14 2 RESPONDING TO HATE How White Supremacists FUNDING HATE Raise Their Money It’s one of the most frequent questions the Anti-Defamation League gets asked: WHERE DO WHITE SUPREMACISTS GET THEIR MONEY? Implicit in this question is the assumption that white supremacists raise a substantial amount of money, an assumption fueled by rumors and speculation about white supremacist groups being funded by sources such as the Russian government, conservative foundations, or secretive wealthy backers. The reality is less sensational but still important. As American political and social movements go, the white supremacist movement is particularly poorly funded. Small in numbers and containing many adherents of little means, the white supremacist movement has a weak base for raising money compared to many other causes. Moreover, ostracized because of its extreme and hateful ideology, not to mention its connections to violence, the white supremacist movement does not have easy access to many common methods of raising and transmitting money. This lack of access to funds and funds transfers limits what white supremacists can do and achieve. However, the means by which the white supremacist movement does raise money are important to understand. Moreover, recent developments, particularly in crowdfunding, may have provided the white supremacist movement with more fundraising opportunities than it has seen in some time. This raises the disturbing possibility that some white supremacists may become better funded in the future than they have been in the past.