A Practical Scheme for Light Rail Extensions in Inner Sydney

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government Gazette of the STATE of NEW SOUTH WALES Number 111 Friday, 7 August 2009 Published Under Authority by Government Advertising

4729 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 111 Friday, 7 August 2009 Published under authority by Government Advertising LEGISLATION Online notification of the making of statutory instruments Week beginning 27 July 2009 THE following instruments were officially notified on the NSW legislation website (www.legislation.nsw.gov.au) on the dates indicated: Proclamations commencing Acts Criminal Organisations Legislation Amendment Act 2009 No 23 (2009-353) — published LW 31 July 2009 Regulations and other statutory instruments Allocation of the Administration of Acts 2009 (No 2—General Allocation) (2009-351) — published LW 27 July 2009 Commercial Vessels Legislation Amendment (Fees, Expenses and Charges) Regulation 2009 (2009-354) — published LW 31 July 2009 Environmental Planning and Assessment Amendment (Site Compatibility Certificates) Regulation 2009 (2009-355) — published LW 31 July 2009 Fair Trading Amendment (Child Restraints) Regulation 2009 (2009-356) — published LW 31 July 2009 Fisheries Management Legislation Amendment (Catch Reporting) Regulation 2009 (2009-357) — published LW 31 July 2009 Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Amendment (Criminal Organisations) Regulation 2009 (2009-358) — published LW 31 July 2009 Management of Waters and Waterside Lands Amendment (Fees) Regulation 2009 (2009-359) — published LW 31 July 2009 Marine Safety (General) Amendment (Fees) Regulation 2009 (2009-360) — published LW 31 July 2009 Public Sector Employment and Management (Departmental Amalgamations) Order 2009 (2009-352) -

Agenda of Strategic Planning and Development Committee

STRATEGIC PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE MEETING A meeting of the STRATEGIC PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE will be held at Waverley Council Chambers, Cnr Paul Street and Bondi Road, Bondi Junction at: 7.30 PM, TUESDAY 3 DECEMBER 2019 Ross McLeod General Manager Waverley Council PO Box 9 Bondi Junction NSW 1355 DX 12006 Bondi Junction Tel. 9083 8000 E-mail: [email protected] Strategic Planning and Development Committee Agenda 3 December 2019 Delegations of the Waverley Strategic Planning and Development Committee On 10 October 2017, Waverley Council delegated to the Waverley Strategic Planning and Development Committee the authority to determine any matter other than: 1. Those activities designated under s 377(1) of the Local Government Act which are as follows: (a) The appointment of a general manager. (b) The making of a rate. (c) A determination under section 549 as to the levying of a rate. (d) The making of a charge. (e) The fixing of a fee (f) The borrowing of money. (g) The voting of money for expenditure on its works, services or operations. (h) The compulsory acquisition, purchase, sale, exchange or surrender of any land or other property (but not including the sale of items of plant or equipment). (i) The acceptance of tenders to provide services currently provided by members of staff of the council. (j) The adoption of an operational plan under section 405. (k) The adoption of a financial statement included in an annual financial report. (l) A decision to classify or reclassify public land under Division 1 of Part 2 of Chapter 6. -

Renaissance of Light Rail in Sydney – Key Environmental Challenges, Opportunities and Solutions

Renaissance of Light Rail in Sydney – Key environmental challenges, opportunities and solutions David Gainsford (MEIANZ) Technical Director, Planning & Environment Services Transport Projects 31Sydney October Light 2014 Rail | 1 Outline • Brief history of trams in Sydney • Current projects • Inner West Extension • CBD and South East Light Rail • Lessons learned for future projects Sydney Light Rail | 2 Sydney Light Rail | 3 Sydney Light Rail | 4 Sydney Light Rail | 5 Sydney Light Rail | 6 Sydney Light Rail | 7 SYDNEY LIGHT RAIL One operator One network High standards of customer experience Opal card integration Sydney Light Rail | 8 Strategic context Sydney Light Rail | 9 Why light rail? Problem Objectives Benefits Improve journey reliability Faster and more reliable public transport Unreliable Improve access to major journey times destinations Reduced congestion Customer Increase sustainable Pedestrian transport amenity Congestion Improve amenity of public spaces Reduced public Operations transport costs Lack of Satisfy long term travel capacity to demand Environmental and support Community growth Facilitate urban health benefits development and economic activity Economic Increased productivity Sydney Light Rail | 10 Light rail capacity Sydney Light Rail | 11 INNER WEST LIGHT RAIL 12.8 km Inner West Light Rail, includes 5.6km extension from Lilyfield to Dulwich Hill, opened March 2014 9 new light rail stops, 23 stops in total Maintenance and stabling facilities at Pyrmont and Rozelle New CAF LRVs Sydney Light Rail | 12 Arlington 2010 -

Rozelle Campus M1

Berry St HUNTLEYS POINT The Point Rd Bay Rd NORTH SYDNEY Burns Bay Rd Bay Burns NEUTRAL BAY Pacific Hwy Kurraba Rd WAVERTON Y A W Union St E G TA CREMORNE POINT OT CHURCH ST WHARF RD C Y A W EN RD GA LAVENDER GLOVER ST BAY CAMPBELL ST Rozelle Campus M1 FREDBERT ST MCMAHONS MILSONS POINT POINT KIRRIBILLI BALMAIN RD PERRY ST 0 100 m Sydney Harbour Sydney HarbourTunnel A40 Sydney Harbour Bridge Victoria Rd Montague St Lyons Rd Sydney RUSSELL LEA DRUMMOYNE Opera BALMAIN Hickson Rd House MILLERS POINT Beattie St Darling St BALMAIN EAST Cahill Expressway Darling St THE ROCKS The Hungry Mile A40 Mullens St SYDNEY ROZELLE Pirrama Rd Royal Victoria Rd Phillip St Botanical Macquarie St Western Distributor Gardens RODD University A4 Cahill Expressway POINT of Sydney Mrs Macquaries Rd (Rozelle) Clarence St Bowman St Sussex St George St Leichhardt Balmain Rd PYRMONT York St The Henley Marine Dr Park Western Distributor Domain M1 See Enlargement Elizabeth St Art Gallery Rd WOOLLOOMOOLOO Rozelle D The Crescent A4 o b Campus POTTS POINT ro y Perry St d Hyde P Balmain Rd LILYFIELD Pitt St d Park MacLeay St A4 Darling Dr Harbour St e Jubilee Cross City Tunnel College St Lilyfield Rd Park Eastern Distributor Cross City Tunnel A4 City West Link William St Darling Dr The Crescent The Glebe Point Rd Wentworth Fig St M1 Pyrmont Bridge Rd Wattle St Park Liverpool St Hawthorne Canal Harris St Oxford St Goulburn St Norton St FOREST Darling Dr Johnston St Moore St LODGE ULTIMO Darlinghurst VictoriaRd St Minogue Cres Wigram Rd HABERFIELD ANNANDALE GLEBE Campbell St Eastern Distributor Balmain Rd HAYMARKET Bay St University of Tasmania 0 250 500 1000 m Booth St Bridge Rd www.utas.edu.au Elizabeth St Foster St Tel: +61 2 8572 7995 (Rozelle Campus) Collins St SURRY LEICHHARDT Central HILLS Leichhardt St Station © Copyright Demap, February 2017 Lee St Ross St Broadway Flinders St PADDINGTON City Rd CHIPPENDALE CAMPERDOWN STRAWBERRY HILLS. -

Initial Project Submissions

M4 Extension M4 PART 3: INITIAL PROJECT SUBMISSIONS M4 Extension NSW GOVERNMENT SUBMISSION TO INFRASTRUCTURE AUSTRALIA TEMPLATE FOR SUMMARIES OF FURTHER PRIORITY PROJECTS JULY 2010 Project Summary (2 pages, excluding attachments) Initiative Name: M4 Extension Location (State/Region(or City)/ Locality): Sydney, NSW Name of Proponent Entity: Roads and Traffic Authority of NSW Contact (Name, Position, phone/e-mail): Paul Goldsmith General Manager, Motorway Projects Phone: 8588 5710 or 0413 368 241 [email protected] Project Description: • Provide a description of the initiative and the capability it will provide. The description needs to provide a concise, but clear description of the initiative’s scope. (approx 3 paragraphs) A motorway connection, mainly in tunnel, from the eastern end of the Western Freeway (M4) at North Strathfield to the western outskirts of the Sydney CBD and the road network near Sydney Airport. It would link M4 to the eastern section of the Sydney Orbital via the Cross City Tunnel and Sydney Harbour Bridge. The eastern section of the M4 (east of Parramatta) would be widened/upgraded. A twin tube tunnel is proposed from North Strathfield to just south of Campbell Road at St Peters with connections to the City West Link at Lilyfield/Rozelle and Parramatta Road/Broadway at Glebe/ Chippendale. A bus only connection at Parramatta Road, Haberfield is also possible. A further tunnel is proposed to connect Victoria Road near Gladesville Bridge to the main tunnel in the Leichhardt area. There is a proposed surface motorway link from just south of Campbell Road to the road network around Sydney Airport probably connecting to Canal Road and Qantas Drive (the latter subject to M5 East Expansion planning and Sydney Airport Corp Ltd agreement) with a potential link to M5 at Arncliffe. -

Store Locations

Store Locations ACT Freddy Frapples Freska Fruit Go Troppo Shop G Shop 106, Westfield Woden 40 Collie Street 30 Cooleman Court Keltie Street Fyshwick ACT 2609 Weston ACT 2611 Woden ACT 2606 IGA Express Supabarn Supabarn Shop 22 15 Kingsland Parade 8 Gwydir Square 58 Bailey's Corner Casey ACT 2913 Maribyrnong Avenue Canberra ACT 2601 Kaleen ACT 2617 Supabarn Supabarn Supabarn Shop 1 56 Abena Avenue Kesteven Street Clift Crescent Crace ACT 2911 Florey ACT 2615 Richardson ACT 2905 Supabarn Supabarn Tom's Superfruit 66 Giles Street Shop 4 Belconnen Markets Kingston ACT 2604 5 Watson Place 10 Lathlain Street Watson ACT 2602 Belconnen ACT 2167 Ziggy's Ziggy's Fyshwick Markets Belconnen Markets 36 Mildura Street 10 Lathlain Street Fyshwick ACT 2609 Belconnen ACT 2167 NSW Adams Apple Antico's North Bridge Arena's Deli Café e Cucina Shop 110, Westfield Hurstville 79 Sailors Bay Road 908 Military Road 276 Forest Road North Bridge NSW 2063 Mosman NSW 2088 Hurstville NSW 2220 Australian Asparagus Banana George Banana Joe's Fruit Markets 1380 Pacific Highway 39 Selems Parade 258 Illawarra Road Turramurra NSW 2074 Revesby NSW 2212 Marrickville NSW 2204 Benzat Holdings Best Fresh Best Fresh Level 1 54 President Avenue Shop 2A, Cnr Eton Street 340 Bay Street Caringbah NSW 2229 & President Avenue Brighton Le Sands NSW 2216 Sutherland NSW 2232 Blackheath Vegie Patch Bobbin Head Fruit Market Broomes Fruit and Vegetable 234 Great Western Highway 276 Bobbin Head Road 439 Banna Avenue Blackheath NSW2785 North Turramurra NSW 2074 Griffith NSW 2680 1 Store Locations -

EPISODE 61 SUBURB SPOTLIGHT on GLADESVILLE Marcus

EPISODE 61 SUBURB SPOTLIGHT ON GLADESVILLE Marcus: Good morning and welcome to another episode of the Sydney property inside podcast, your weekly podcast series that talks about all things property related in the city of Sydney. Michelle, how are you doing this fine morning? Michelle: Good, how are you? Marcus: Very very well. So today, we are going to back to one of our series which is the Suburbs Spotlight series and today, we're focused on Gladesville. Michelle: I know Gladesville. I know it well, I used to live there for a long time, actually. Marcus: Oh did you, I didn't know? Oh wow. Michelle: Yeah, I did. Marcus: 'Cause I personally don't know that much about Gladesville so this was certainly interesting reading for myself. Michelle: Yeah, Gladesville is a really interesting suburb. For those of you who don't know where it is, it's on the lower North Shore, northern suburbs of Sydney although sometimes it's counted as being part of the Inner West now, too. So it's situated on the northern banks of the Parramatta river and it's next to Hunters Hill to the northeast and Boronia Park to the north, with Ryde to the western side of it. It's approximately 10 Ks from the city and it's placed in between the local government area of the City of Ryde and the municipality of Hunters Hill. Michelle: So it's really got a very rich history, most of which I found on the dictionary of Sydney which is a fantastic website with lots of information about the history of different suburbs. -

Temporary Construction Site: Victoria Road, Rozelle

Community Update July 2018 Western Harbour Tunnel Temporary construction site: Victoria Road, Rozelle Western Harbour Tunnel is a The NSW Government has now major transport infrastructure A temporarily tunnelling site for Western Harbour Tunnel is released the proposed project project that makes it easier, proposed adjacent to Victoria reference design and there will faster and safer to get around Road, Rozelle. be extensive community and Sydney. This site is only needed stakeholder engagement over the temporarily and no major coming months. As Sydney continues to grow, our permanent facilities will be located transport challenge also increases We now want to hear what here. The site will be left clear for you think about the proposed and congestion impacts our future urban renewal. economy. reference design. Roads and Maritime recognises Your feedback will help us further While the NSW Government actively the importance of this site as refine the design before we seek manages Sydney’s daily traffic the home of the Balmain Tigers demands and major new public Leagues Club and will work with planning approval. transport initiatives are underway, it’s all parties concerned. There will be further extensive clear that even more must be done. community engagement once the Seaforth Spit Bridge Environmental Impact Statement Western Harbour Tunnel will provide is on public display. Northbridge a new motorway tunnel connection Balgowlah Heights Artarmon across Sydney Harbour between Seaforth Rozelle and the Warringah Freeway Spit Bridge near North Sydney. Northbridge Balgowlah Heights Artarmon It will form a new western bypass Lane Cove of the Sydney CBD, providing an Cammeray Ernest St alternative to the heavily congested St Leonards Mosman Falcon St Sydney Harbour Bridge, Western Lane Cove Crows Nest OFF Cremorne Distributor and Anzac Bridge. -

Speed Camera Locations

April 2014 Current Speed Camera Locations Fixed Speed Camera Locations Suburb/Town Road Comment Alstonville Bruxner Highway, between Gap Road and Teven Road Major road works undertaken at site Camera Removed (Alstonville Bypass) Angledale Princes Highway, between Hergenhans Lane and Stony Creek Road safety works proposed. See Camera Removed RMS website for details. Auburn Parramatta Road, between Harbord Street and Duck Street Banora Point Pacific Highway, between Laura Street and Darlington Drive Major road works undertaken at site Camera Removed (Pacific Highway Upgrade) Bar Point F3 Freeway, between Jolls Bridge and Mt White Exit Ramp Bardwell Park / Arncliffe M5 Tunnel, between Bexley Road and Marsh Street Ben Lomond New England Highway, between Ross Road and Ben Lomond Road Berkshire Park Richmond Road, between Llandilo Road and Sanctuary Drive Berry Princes Highway, between Kangaroo Valley Road and Victoria Street Bexley North Bexley Road, between Kingsland Road North and Miller Avenue Blandford New England Highway, between Hayles Street and Mills Street Bomaderry Bolong Road, between Beinda Street and Coomea Street Bonnyrigg Elizabeth Drive, between Brown Road and Humphries Road Bonville Pacific Highway, between Bonville Creek and Bonville Station Road Brogo Princes Highway, between Pioneer Close and Brogo River Broughton Princes Highway, between Austral Park Road and Gembrook Road safety works proposed. See Auditor-General Deactivated Lane RMS website for details. Bulli Princes Highway, between Grevillea Park Road and Black Diamond Place Bundagen Pacific Highway, between Pine Creek and Perrys Road Major road works undertaken at site Camera Removed (Pacific Highway Upgrade) Burringbar Tweed Valley Way, between Blakeneys Road and Cooradilla Road Burwood Hume Highway, between Willee Street and Emu Street Road safety works proposed. -

Contextual Analysis and Urban Design Objectives

Rozelle Interchange Urban Design and Landscape Plan Contextual Analysis and Urban Design Objectives Artists impression: Pedestrian view along Victoria Road Caption(Landscape - Image shown description at full maturity and is indicative only). 03 White Bay Power Station Urban Design Objectives 3 Contextual analysis 3.1 Contextual analysis Local context WestConnex will extend from the M4 Motorway at The Rozelle Interchange will be a predominately Parramatta to Sydney Airport and the M5 underground motorway interchange with entry and Motorway, re-shaping the way people move exit points that connect to the wider transport through Sydney and generating urban renewal network at City West Link, Iron Cove and Anzac opportunities along the way. It will provide the Bridge. critical link between the M4 and M5, completing Sydney’s motorway network. Iron Cove and Rozelle Rail Yards sit on and are adjacent to disconnected urban environments. While the character varies along the route, the These conditions are the result of the historically WestConnex will be sensitively integrated into the typical approach to building large individual road built and natural environments to reconnect and systems which disconnect suburbs and greatly strengthen local communities and enhance the reduce the connectivity and amenity of sustainable form, function, character and liveability of Sydney. modes of transport such as cycling and walking. Rather than adding to the existing disconnection, An analysis of the Project corridor was undertaken the Project will provide increased -

AN OVERVIEW of the CITY WEST CYCLE-LINK Prepared By: Ecotransit Sydney Date: 1 June 2010 Authorised by the Executive Committee O

AN OVERVIEW OF THE CITY WEST CYCLE-LINK Prepared by: EcoTransit Sydney Date: 1 June 2010 Authorised by the Executive Committee of EcoTransit Sydney The submission (including covering letters) consists of: 14 pages Contact person for this submission: John Bignucolo 02 9713 6993 [email protected] Contact details for EcoTransit Sydney, Inc.: PO Box 630 Milsons Point NSW 1565 See our website at: www.ecotransit.org.au City West Cycle-Link 1 EcoTransit Sydney An Overview of the City West Cycle-Link Summary This document presents a proposal for the City West Cycle-Link, a new cycling facility that would: 1. Provide a cycling and walking tunnel running across and under the City West Link Road, from Darley Road in the west to Derbyshire Road in the east; 2. Offer a safe alternative to crossing the slip lane running from the City West Link Road onto Darley Road; 3. Closely integrate with the proposed Norton 2 (James St) light rail stop, increasing the flow of people in the vicinity of the stop, and thereby enhancing the sense of safety of light rail commuters; 4. Allow cyclists to bypass the climb up Lilyfield Road between the Hawthorne Canal and James Street; 5. Connect with and extend the cycling route along Darley Road proposed as part of the GreenWay project; 6. Provide a grade-separated alternative to Lilyfield Road by creating a comparatively flat and direct connection to the Anzac Bridge cycleway at White Bay via the Lilyfield rail cutting and the Rozelle rail lands. In order to determine its scope and feasibility, EcoTransit Sydney requests that the NSW government via the Department of Transport and Infrastructure (NSWTI) undertake an investigation of the proposal as it has the required technical skills and resources for the task. -

Renaissance of Light Rail in Sydney – Key Environmental Challenges, Opportunities and Solutions

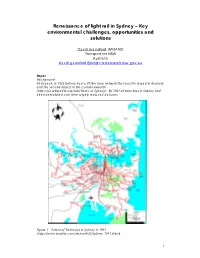

Renaissance of light rail in Sydney – Key environmental challenges, opportunities and solutions David Gainsford (MEIANZ) Transport for NSW Australia [email protected] Paper: Background At its peak, in 1923 Sydney had a 291km tram network that was the largest in Australia and the second largest in the Commonwealth (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trams_in_Sydney). By 1961 all tram lines in Sydney had been demolished and were largely replaced by buses. Figure 1 – Extent of Tramways in Sydney in 1947 (http://www.tundria.com/trams/AUS/Sydney-1947.shtml) 1 In 1997 light rail services began operations in Sydney again with a service between Central and Wentworth Park, extended to Lilyfield in 2000. Most of this line operates on a disused freight rail line. The NSW Government released the ‘Sydney’s Light Rail Future’ document in December 2012 (NSW Government, 2012) which details a renaissance of light rail projects in Sydney. The first new project detailed in this document was opened in March 2014 consisting of the 5.6km Inner West extension to the existing Lilyfield to Central Light Rail line (total length now 12.8km). Planning approval has now been granted to construct the $1.6 billion 12km long CBD and South East Light Rail (CSELR). In June 2014, the NSW Government committed $400 million to the commencement of a Western Sydney Light Rail, centred on Parramatta. Light rail projects are also proposed in Newcastle and in Canberra. Figure 2 - Current and Proposed Sydney Light Rail Network 2 Figure 3 – Potential Parramatta-based Light Rail Alignment Options (http://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/newslocal/parramatta/extensive-light-rail- system-will-transform-transport-in-western-sydney/story-fngr8huy-1226958390644) The light rail projects are promoted as providing improved reliability of service and capacity to the denser urban areas that they serve.