Rural Connections Nov. 2009 from the Director

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stone-Boiling Maize with Limestone: Experimental Results and Implications for Nutrition Among SE Utah Preceramic Groups Emily C

Agronomy Publications Agronomy 1-2013 Stone-boiling maize with limestone: experimental results and implications for nutrition among SE Utah preceramic groups Emily C. Ellwood Archaeological Investigations Northwest, Inc. M. Paul Scott United States Department of Agriculture, [email protected] William D. Lipe Washington State University R. G. Matson University of British Columbia John G. Jones WFoasllohinwgt thion Sst atnde U naiddveritsitiony al works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/agron_pubs Part of the Agricultural Science Commons, Agronomy and Crop Sciences Commons, Food Science Commons, and the Indigenous Studies Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ agron_pubs/172. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Agronomy at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Agronomy Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Archaeological Science 40 (2013) 35e44 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/jas Stone-boiling maize with limestone: experimental results and implications for nutrition among SE Utah preceramic groups Emily C. Ellwood a, M. Paul Scott b, William D. Lipe c,*, R.G. Matson d, John G. Jones c a Archaeological -

Nutrient Content

USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard ReferenceRelease 28 Nutrients: 20:5 n-3 (EPA) (g) Food Subset: All Foods Ordered by: Nutrient Content Measured by: Household Report Run at: September 18, 2016 04:44 EDT 20:5 n-3 (EPA)(g) NDB_No Description Weight(g) Measure Per Measure 04591 Fish oil, menhaden 13.6 1.0 tbsp 1.791 15197 Fish, herring, Pacific, cooked, dry heat 144.0 1.0 fillet 1.788 04593 Fish oil, salmon 13.6 1.0 tbsp 1.771 04594 Fish oil, sardine 13.6 1.0 tbsp 1.379 15040 Fish, herring, Atlantic, cooked, dry heat 143.0 1.0 fillet 1.300 83110 Fish, mackerel, salted 80.0 1.0 piece (5-1/2" x 1-1/2" x 1/2") 1.295 15041 Fish, herring, Atlantic, pickled 140.0 1.0 cup 1.180 15046 Fish, mackerel, Atlantic, raw 112.0 1.0 fillet 1.006 35190 Salmon, red (sockeye), filets with skin, smoked (Alaska Native) 108.0 1.0 filet 0.977 15094 Fish, shad, american, raw 85.0 3.0 oz 0.923 15210 Fish, salmon, chinook, cooked, dry heat 85.0 3.0 oz 0.858 15078 Fish, salmon, chinook, raw 85.0 3.0 oz 0.857 04590 Fish oil, herring 13.6 1.0 tbsp 0.853 15043 Fish, herring, Pacific, raw 85.0 3.0 oz 0.824 15208 Fish, sablefish, cooked, dry heat 85.0 3.0 oz 0.737 15236 Fish, salmon, Atlantic, farmed, raw 85.0 3.0 oz 0.733 15181 Fish, salmon, pink, canned, without salt, solids with bone and liquid 85.0 3.0 oz 0.718 15088 Fish, sardine, Atlantic, canned in oil, drained solids with bone 149.0 1.0 cup, drained 0.705 15116 Fish, trout, rainbow, wild, cooked, dry heat 143.0 1.0 fillet 0.669 15237 Fish, salmon, Atlantic, farmed, cooked, dry heat 85.0 3.0 oz 0.586 15239 -

Hopi Crop Diversity and Change

J. Ethtlobiol. 13(2);203-231 Winter 1993 HOPI CROP DIVERSITY AND CHANGE DANIELA SOLER I and DAVID A. CLEVELAND Center for People, Food, and Environment 344 South Third Ave. Thcson, AZ 85701 ABSTRACT.-There is increasing interest in conserving indigenous crop genetic diversity ex situ as a vital resource for industrial agriculture. However, crop diver sity is also important for conserving indigenously based, small-scale agriculture and the farm communities which practice it. Conservation of these resources may best be accomplished, therefore, by ensuring their survival in situ as part of local farming communities like the Hopi. The Hopi are foremost among Native Ameri can farmers in the United States in retaining their indigenous agriculture and folk crop varieties (FVs), yet little is known about the dynamics of change and persis tence in their crop repertoires. The purpose of our research was to investigate agricultural crop diversity in the form of individual Hopi farmers' crop reper toires, to establish the relative importance of Hopi FVs and non·Hopi crop vari eties in those repertoires, and to explore the reasons for change or persistence in these repertoires. We report data from a 1989 survey of a small (n "" 50), oppor tunistic sample of Hopi farmers and discuss the dynamics of change based on cross·sectional comparisons of the data on crop variety distribution, on farmers' answers to questions about change in their crop repertoires, and on the limited comparisons possible with a 1935 survey of Hopi seed sources. Because ours is a small, nonprobabilistic sample it is not possible to make valid extrapolations to Hopi farmers in general. -

Now You're Cooking!

(NCL)DRYINGCORNNAVAJO 12 earsfreshcorninhusks Carefullypeelbackhusks,leavingthemattachedatbaseofcorn. cleancorn,removingsilks.Foldhusksbackintoposition.Placeon wirerackinlargeshallowbakingpan.(Allowspacebetweenearsso aircancirculate.)Bakein325degreeovenfor11/2hours.Cool. Stripoffhusks.Hangcorn,soearsdonottouch,inadryplacetill kernelsaredry,atleast7days.Makesabout6cupsshelledcorn. From:ElayaKTsosie,aNativeNavajo.SheteachesNativeAmerican HistoryatattwodifferentNewYorkStateColleges. From:Mignonne Yield:4servings (NCL)REALCANDIEDCORN 222cup frozencornkernels 11/2 cup sugar 111cup water Hereisacandyrecipeforya:)Idon'tletthecorngettoobrown.I insteadtakeitoutwhenit'sanicegoldcolor,drainit,rollitin thesugar,thendryitinaverylowoven150200degrees.Youcan alsodopumpkinthiswaycutinthinstrips.Addhoneyduringthe lastpartofthecookingtogiveitamorenaturaltastebutdon't boilthehoneyasitwillmakeitgooey. Inlargeskillet,combinecorn,1cupofthesugar,andwater.Cook overmediumheat,stirringoccasionallyuntilcornisdeepgoldenin color,about45to60minutes.Drain,thenrollinremainingsugar. Spreadinasinglelayeronbakingsheetandcool.Storeinatightly sealedcontainerorbag.Useastoppingsforicecream,inpuddings, custards,offillings,orasasubstitutefornutsinbaking.Ohgood rightoutofthebagtoo! From:AnnNelson Yield:4servings Page 222 (NCL)SHAWNEERECIPEFORDRYINGCORN 111corn Selectcornthatisfirmbutnothard.Scrapeoffofcobintodeep pan.Whenpanisfull,setinslowovenandbakeuntilthoroughly heatedthrough,anhourormore.Removefromovenandturnponeout tocool.Latercrumbleondryingboardinthesunandwhenthoroughly -

(Hopi Office of Prevention & Intervention) Cancer Support Services

H.O.P.I. (Hopi Office of Prevention & Intervention) Cancer Support Services • A sovereign nation located in northeastern Arizona • Has a population exceeding 14,000 members • Reservation land base encompasses more than 1.5 million acres within Coconino and Navajo counties • Traditional tribal structure consist of 12 autonomous villages on three mesas including 1 additional community • Have survived centuries as a Tribe, maintaining their culture, language and religion despite outside influences • The Tribal leadership consists of Village Kikmongwi/Governors, an elected Chairman, Vice Chairman and representatives of each village • These elected representatives guide the Hopi Tribe in U.S. and State government affairs. HOPI BREAST & CERVICAL CANCER EARLY DETECTION PROGRAM • Originally established under the name of “Hopi Women’s Health Program” • Conceived and initiated in 1996 to provide breast & cervical cancer screening services to women • The Hopi Tribe has had the support of the CDC “Screening Program” National Breast & Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program • Since its inception, the Screening Program has provided thousands of women with cancer education, clinical breast exams, mammograms and cervical cancer screening OTHER HCSS PROGRAMS This program engages in outreach organizing & education activities and helps navigate women and Colorectal Program men through the screening process. A not for profit like organization established in 2005 to assist cancer patients with travel cost while they receive treatment at off reservation locations. Donations support the Fund The Partnership for Native American Cancer Prevention (NACP) is an outreach collaboration between HCSS, NAU, UofA, and three Arizona tribes. This program is supported through a partnership with the Arizona Department of Health Services to provide commercial tobacco prevention/education, and organizing a Hopi Youth Tobacco Coalition CHALLENGES HOPI, like most Indian Reservations is beset with health disparities in the provision of healthcare. -

Palliative Care for Advanced Alzheimer's and Dementia

SABBAGH PALLIATIVE CARE for MARTIN Advanced Alzheimer’s and Dementia Guidelines and Standards for Evidence-Based Care PALLIATIVE CAREPALLIATIVE for THE DESERT SOUTHWEST CHAPTER OF THE ALZHEIMER’S ASSOCIATION Gary A. Martin, PhD PALLIATIVE Marwan N. Sabbagh, MD, Editors “This book…provides important information on best practices and appropriate ways to care for a person with advanced Alzheimer’s and dementia. Drs. Martin CARE for and Sabbagh have assembled a team of experts to help craft recommendations that should ultimately become standards that all professional caregivers adopt.” —MICHAEL REAGAN Son of former President Ronald Reagan Dementia and Alzheimer’s Advanced President, Reagan Legacy Foundation Advanced his book testifi es that caregivers can have a monumental impact on the lives of persons with Tadvanced dementia. Through specialized programming and a renewed effort toward patient- centered care, caregivers can profoundly enrich the quality of life for these persons. Providing guidelines for health care professionals, caregivers, and family members, this book introduces palliative care programs and protocols for the treatment of people with advanced dementia. Alzheimer’s Designed to guide professional caregivers in meeting the needs of patients and their families, the content provides insight into the philosophy, assessment, planning, implementation, and evaluation measures involved in interdisciplinary palliative care. The guidelines and standards of care are based on contributions from nurses, physical therapists, social workers, -

Diccionario Escolar

Diccionario Escolar Ik´ıitu kuwas´ıini – tawi-kuwas´ıini Iquito – Castellano Tercera edici´on Centro del Idioma Ik´ıitu San Antonio de Pintuyacu Diccionario Escolar Ik´ıitu kuwas´ıini – tawi-kuwas´ıini Iquito – Castellano Compilado por: Christine Beier Lev Michael Basado en los conocimientos de los especialistas: Jaime Pacaya Inuma Ema Llona Yareja Hermenegildo D´ıaz Cuyasa Ligia Inuma Inuma Tercera edici´on Agosto 2019 Centro del Idioma Ik´ıitu San Antonio de Pintuyacu, Loreto, Per´u © 2019 Cabeceras Aid Project Impreso en Iquitos por Cabeceras Aid Project Agradecimientos Este diccionario escolar es uno de los productos del trabajo colaborativo del equipo de investigaci´ondel proyecto de documentar y recuperar el idioma ik´ıitu, conocido como ‘iquito’ en el castellano. El proyecto fue lanzado en junio del a˜no 2001 y es basado en el Centro del Idioma Ik´ıitu en la comunidad iquito de San Antonio de Pintuyacu. La primera fase de trabajo intensivo culmin´oen diciembre 2006. La actual fase de trabajo intensivo se inici´oen mayo 2014, con el fin de profundizar, mejorar y emitir un nuevo juego de materiales en y acerca del idioma. Cada persona que disfruta de este diccionario escolar debe mucho a todos los especialistas del idioma iquito, quienes han compartido tanto de sus conocimientos, su sabidur´ıa y su tiempo con los ling¨uistas del Centro del Idioma Ik´ıitu. Sin el compromiso de los especialistas, el proyecto de documentaci´ondel idioma no hu- biera podido existir. En especial, agradecemos a los se˜nores Jaime Pacaya Inuma y Hermenegildo D´ıaz Cuyasa y a las se˜noras Ema Llona Yareja y Ligia Inuma Inuma. -

The Return of True Agricultural Localism

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2020 GROWING A REGIONAL FOOD SYSTEM THE RETURN OF TRUE AGRICULTURAL LOCALISM VOLUME 12 NUMBER 4 GREENFIRETIMES.COM PUBLISHER GREEN EARTH PUBLISHING, LLC EDITOR-IN-CHIEF SETH ROFFMAN / [email protected] PLEASE SUPPORT GREEN FIRE TIMES GUEST ASSOCIATE EDITOR ERIN ORTIGOZA Green Fire Times provides a platform for regional, community-based DESIGN WITCREATIVE voices—useful information for residents, businesspeople, students and COPY EDITOR STEPHEN KLINGER visitors—anyone interested in the history and spirit of New Mexico and the Southwest. One of the unique aspects of GFT is that it offers CONTRIBUTING WRITERS ANITA ADALJA, JAIME CHÁVEZ, JULIANA multicultural perspectives and a link between the green movement and CIANO, VANESSA COLÓN, MARTHA COOKE, ZOE FINK, LUCY GENT FOMA, LISA traditional cultures. B. FRIEDLAND, ROD GESTEN, ISABELL JENNICHES, GILLIAN JOYCE, MELANIE MARGARITA KIRBY, JACK LOEFFLER, FAITH MAXWELL, RACHEL MOORE, KYLE Storytelling is at the heart of community health. GFT shares stories MALONE, MIKE MUSIALOWSKI, SAYRAH NAMASTE, ANDREW NEIGHBOR, CORILIA of hope and is an archive for community action. In each issue, a ORTEGA, ERIN ORTIGOZA, SONORA RODRÍGUEZ, ERNIE RIVERA, SETH ROFFMAN, small, dedicated staff and a multitude of contributors offer articles CHRISTINA M. ROGERS, MICAH ROSEBERRY, MIGUEL SANTISTEVAN, MELYNN documenting projects supporting sustainability—community, culture, SCHUYLER, JAMES SKEET, NINA YOZELL-EPSTEIN, MARK WINNE environment and regional economy. CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS ROSE CARMONA, JAIME CHÁVEZ, Green Fire Times is now operated by an LLC owned by a nonprofit VANESSA COLÓN, CORE VISUAL, BYRON FLESHER, MARY GAUL, GABRIELLA MARKS, educational organization (Est. 1972, swlearningcenters.org). Obviously, it BARBARA MOHON, JIM O’DONNELL, MELANIE MARGARITA KIRBY, ERIN ORTIGOZA, is very challenging to continue to produce a free, quality, independent SETH ROFFMAN, MICAH ROSEBERRY, MIGUEL SANTISTEVAN, JAMES SKEET publication. -

Regular Catalog.Pdf

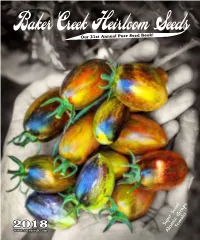

Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds e Our 21st Annual Pure Seed Book! 2018 www.rareseeds.com Super Sweet Atomic Grape To m ato “...the Indiana Jones of Seeds.” -The New York Times Magazine The Gettle family in our herb and flower garden. Satisfaction The girls, Sasha, 10 and Malia, 4, love growing GUARANTEED things in their gardens. for 2 years!* Welcome To Our 21st Seed Catalog! Dear Gardening Friends, Not only do our travels yield new seeds, but We want to continue the tradition of uniting also friends from across the globe who united people around the dinner table, in the garden, We are very thrilled to be printing our 21st with us in the passion to preserve the seeds of and on the farm. We must continue to fight the annual catalog in 2018, and we think this year’s the people, in the hands of people, and free global takeover of the seed and food supply selection of colorful heirlooms is the best yet. We from corporate control, patents and GMOs. while at the same time preserve the seeds from are more and more focused on introducing super Each year the resistance to corporate, GMO, our past, seeds that have built our cultures and colorful varieties that are packed with nutrition factory farming continues to grow, both in are often times are the only living link to our and flavor. We are especially happy to be bringing America, and often times faster internationally. past, our ancesters and our heritage. you a host of new corn varieties after spending People want the food their grandmothers grew Please join us in celebrating our seed heri- years to keep these pure from toxic, GMO pollen. -

Dietary Mineral Ecology of the Hopi

]. Ethnobiol. 1 (I): 84-94 May 1981 DIETARY MINERAL ECOLOGY OF THE HOPI HARRIET V. KUHNLEIN University of British Columbia, Division of Human Nutrition, Vancouver, B.C., Canada V6T lW5 ABSTRAC1.-The Hopi are considered one of America's oldest Native Indian groups who continue to live on traditional lands. In modem times, they have relinquished many of their earlier cultural practices, including those related to agriculture and diet. Foods consumed have changed from the earlier panern ofcorn, beans, and squash, augmented with wild plants and animals to a contemporary diet which contains a varietyoffoods imponed to the reserva tion. A survey of 420 Hopi women and children showed that less than 25% consume one item of indigenous food each day and that the variety of traditional foods consumed has decreased dramatically from that described in the early anthropological literature. The changing diet presupposed changes in nutritional status. Mineral analysisof traditional Hopi foods reveals high levels of all nutritionally essential elements. Additionally, Hopi cultural practices reinforced the use of unusual mineral-rich plant foods and salts which were of nutritional importance when the diet was limited to animal foods. Seventeenth century and contempor ary Hopi deciduous teeth were analyzed for several minerals. Whilecalciumand phosphorus were similar in both groups, theearlier group had significantly higher levels of strontium and the laller group had higher levels of zinc, copper and lead. INTRODUCTION The Hopi are considered one of America's oldest Native Indian groups who continue to live on tradilionallands. Hopi villages on the mesas of northeastern Arizona (Fig. I) have been continuously inhabited since A.D. -

Specialty Corns Cooperative Extension Service T A

IC EX O S M Specialty Corns Cooperative Extension Service T A W T E College of Agriculture and E N U Home Economics N Y I I T Guide H-232 V E R S George W. Dickerson, Extension Horticulture Specialist This publication is scheduled to be updated and reissued 2/08. History (tissue surrounding the embryo that provides food for the seed’s growth). Five hundred years ago, Columbus became one of The most common types of corn include flint, the first Europeans to set eyes on maize or corn (Zea flour, dent, pop, sweet, and waxy. The physical ap- mays), the foundation of most great New World civili- pearance of each kernel type is determined by its pat- zations, including those of the Incas, Mayans, and Az- tern of endosperm composition as well as quantity tecs. In 1540, Coronado found pueblo Indians grow- and quality of endosperm (fig. 1). ing corn under irrigation in the American Southwest. A seventh type of corn called pod or tunicate may The Jamestown Colony learned how to grow corn also be characterized by flint, dent, flour, sweet, pop, from the Indians in 1608, and corn helped keep the or waxy endosperms. In pod corns, however, each in- Pilgrims alive during the winter of 1620. dividual kernel is enclosed in a glume, or husk. These The inability of corn to survive in the wild on its types have little commercial value except as an orna- own makes its ancestry a puzzle. Probably the oldest ment. known remains of corn are cobs dating back 7000 Kernels of flint corn have mostly hard, glassy en- years found in Tehucan, Mexico. -

Seedlisting Many Ways to Get Seeds

2018 Seedlisting Many Ways to Get Seeds Agricultural biodiversity is most valuable when it is used to strengthen local food and farming systems. Native Seeds/SEARCH strives to provide public access to seeds of regionally appropriate crop varieties through our various seed distribution programs. In addition to retail sales , individuals and organizations can receive access to seeds via: Community Seed Grants We provide free seeds for organizations (including schools, food banks, senior centers, and seed libraries) working to promote nutrition, food security, education, and/or community resilience. Projects that will clearly benefit underprivileged groups are especially encouraged. Applications are reviewed in January, May, and September. See page 5 for more information. Native American Seed Request We provide a limited number of seed packets at no or reduced cost to Native American individuals. See page 9 for more information and details on how to order. Bulk Seed Exchange To encourage small-scale farmers to grow, save, and promote arid-adapted varieties, we provide available start-up bulk seed quantities in exchange for a return of a portion of the seeds after a successful harvest. Seed Library If you are in Tucson, Arizona, we encourage you to visit our seed library located in our Retail Store. The library is open to all to facilitate the free distribution of locally adapted seeds and increase regional seed sovereignty. Donations of seed to the library are welcome! Visit www.nativeseeds.org , email us at [email protected] , or call us at 520.622.0830 for more information. Community Seed Grant Recipient: Pollinator Garden at Raul M.