Gareth Bryant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women and the Communist Party of Canada, 1932-1941, with Specific Reference to the Activism of Dorothy Livesay and Jim Watts

Mother Russia and the Socialist Fatherland: Women and the Communist Party of Canada, 1932-1941, with specific reference to the activism of Dorothy Livesay and Jim Watts by Nancy Butler A thesis submitted to the Department of History in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada November 2010 Copyright © Nancy Butler, 2010 ii Abstract This dissertation traces a shift in the Communist Party of Canada, from the 1929 to 1935 period of militant class struggle (generally known as the ‘Third Period’) to the 1935-1939 Popular Front Against Fascism, a period in which Communists argued for unity and cooperation with social democrats. The CPC’s appropriation and redeployment of bourgeois gender norms facilitated this shift by bolstering the CPC’s claims to political authority and legitimacy. ‘Woman’ and the gendered interests associated with women—such as peace and prices—became important in the CPC’s war against capitalism. What women represented symbolically, more than who and what women were themselves, became a key element of CPC politics in the Depression decade. Through a close examination of the cultural work of two prominent middle-class female members, Dorothy Livesay, poet, journalist and sometime organizer, and Eugenia (‘Jean’ or ‘Jim’) Watts, reporter, founder of the Theatre of Action, and patron of the Popular Front magazine New Frontier, this thesis utilizes the insights of queer theory, notably those of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick and Judith Butler, not only to reconstruct both the background and consequences of the CPC’s construction of ‘woman’ in the 1930s, but also to explore the significance of the CPC’s strategic deployment of heteronormative ideas and ideals for these two prominent members of the Party. -

The Popular Front: Roadblock to Revolution

Internationalist Group League for th,e Fourth International The Popular Front: Roadblock to Revolution Volunteers from the anarcho-syndicalist CNT and POUM militias head to the front against Franco's forces in Spanish Civil War, Barcelona, September 1936. The bourgeois Popular Front government defended capitalist property, dissolved workers' militias and blocked the road to revolution. Internationalist Group Class Readings May 2007 $2 ® <f$l~ 1162-M Introduction The question of the popular front is one of the defining issues in our epoch that sharply counterpose the revolution ary Marxism of Leon Trotsky to the opportunist maneuverings of the Stalinists and social democrats. Consequently, study of the popular front is indispensable for all those who seek to play a role in sweeping away capitalism - a system that has brought with it untold poverty, racial, ethnic, national and sexual oppression and endless war - and opening the road to a socialist future. "In sum, the People's Front is a bloc of the bourgeoisie and the proletariat," Trotsky wrote in December 1937 in re sponse to questions from the French magazine Marianne. Trotsky noted: "When two forces tend in opposite directions, the diagonal of the parallelogram approaches zero. This is exactly the graphic formula of a People's Front govern ment." As a bloc, a political coalition, the popular (or people's) front is not merely a matter of policy, but of organization. Opportunists regularly pursue class-collaborationist policies, tailing after one or another bourgeois or petty-bourgeois force. But it is in moments of crisis or acute struggle that they find it necessary to organizationally chain the working class and other oppressed groups to the class enemy (or a sector of it). -

Shaping the Inheritance of the Spanish Civil War on the British Left, 1939-1945 a Thesis Submitted to the University of Manches

Shaping the Inheritance of the Spanish Civil War on the British Left, 1939-1945 A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Master of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2017 David W. Mottram School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Table of contents Abstract p.4 Declaration p.5 Copyright statement p.5 Acknowledgements p.6 Introduction p.7 Terminology, sources and methods p.10 Structure of the thesis p.14 Chapter One The Lost War p.16 1.1 The place of ‘Spain’ in British politics p.17 1.2 Viewing ‘Spain’ through external perspectives p.21 1.3 The dispersal, 1939 p.26 Conclusion p.31 Chapter Two Adjustments to the Lost War p.33 2.1 The Communist Party and the International Brigaders: debt of honour p.34 2.2 Labour’s response: ‘The Spanish agitation had become history’ p.43 2.3 Decline in public and political discourse p.48 2.4 The political parties: three Spanish threads p.53 2.5 The personal price of the lost war p.59 Conclusion p.67 2 Chapter Three The lessons of ‘Spain’: Tom Wintringham, guerrilla fighting, and the British war effort p.69 3.1 Wintringham’s opportunity, 1937-1940 p.71 3.2 ‘The British Left’s best-known military expert’ p.75 3.3 Platform for influence p.79 3.4 Defending Britain, 1940-41 p.82 3.5 India, 1942 p.94 3.6 European liberation, 1941-1944 p.98 Conclusion p.104 Chapter Four The political and humanitarian response of Clement Attlee p.105 4.1 Attlee and policy on Spain p.107 4.2 Attlee and the Spanish Republican diaspora p.113 4.3 The signal was Greece p.119 Conclusion p.125 Conclusion p.127 Bibliography p.133 49,910 words 3 Abstract Complexities and divisions over British left-wing responses to the Spanish Civil War between 1936 and 1939 have been well-documented and much studied. -

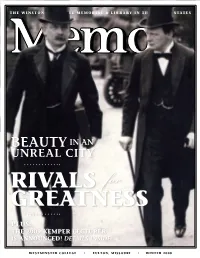

The 2009 Kemper Lecturer Is Announced! Details Inside

THE WINSTON CHURCHILL MEMORIAL & LIBRARY IN THE UNITED STATES PLUS: THE 2009 KEMPER LECTURER IS ANNOUNCED! DETAILS INSIDE... WESTMINSTER COLLEGE | FULTON, MISSOURI | WINTER 2008 MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Board of Governors Association of Churchill Fellows William H. Tyler Chairman & Senior Fellow Carmel, California elcome to the winter edition of the Memo and a packed Earl Harbison St. Louis, Missouri edition it is too. We have two very interesting articles the first is from Dr. Richard Toye, who writes about Whitney R. Harris St. Louis, Missouri the relationship between Sir Winston and his great friend and rival, W William Ives David Lloyd George. This article is a distillation of Dr. Toye’s recent Chapel Hill, North Carolina book, entitled appropriately enough Churchill and Lloyd George, Rivals R. Crosby Kemper, III for Greatness. I hope the article whets your appetite sufficiently that Kansas City, Missouri you purchase the book- it is highly recommended! Additionally, as we Barbara Lewington look ahead to the 40th anniversary of the dedication of St. Mary, the St. Louis, Missouri Virgin, Aldermanbury, we have a fascinating piece by Carolyn Perry, Richard J. Mahoney Professor of English at Westminster College. Dr. Perry links a number St. Louis, Missouri of themes in her article; that of the Churches in the City of London, John R. McFarland the great poem by TS Eliot ‘The Wasteland’ (which features many St. Louis, Missouri references to City Churches) and of course the significant local relevance Jean Paul Montupet of Eliot himself, a Missouri native and confirmed Anglophile. St. Louis, Missouri William R. Piper St. -

British War Cabinet

British War Cabinet Dear Delegates to the British War Cabinet, Welcome to the British War Cabinet (BWC) and University of Michigan Model United Nations Conference (UMMUN). I would like to extend a special welcome to those of you new to UMMUN. This committee will hopefully prove to be very exciting because of the dynamics and, of course, you, the delegates. This year, we have decided to create a new committee to fit the growing needs of delegates. You will be asked to tackle difficult situations quickly and keep your wits about you. Also, with no set topic, I expect each delegate to be well-versed in the person he or she represents as well as his or her powers and areas expertise. I do not expect you to become experts, but I do expect you to know what information you should know so that it may be called upon, if needed. This is a small committee, and as such, I will expect you all to be very active during the conference. I have a great staff this year. Dana Chidiac is my Assitant Director. She is a second year student concentrating in English. My name is Nicole Mazur. I am a fourth year student at UM, double concentrating in Political Science and Communications. My model UN career began when I got to college and have since been to conferences at University of Pennsylvania, Harvard University, University of Chicago, McGill University, and Georgetown University. Last year for UMMUN, I was the Director of the United States National Security Council. If you have any questions, please feel free to email me. -

The Political Thought of Aneurin Bevan Nye Davies Thesis

The Political Thought of Aneurin Bevan Nye Davies Thesis submitted to Cardiff University in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Law and Politics September 2019 DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of …………………………(insert MCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available online in the University’s Open Access repository and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available online in the University’s Open Access repository and for inter-library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… WORD COUNT 77,992 (Excluding summary, acknowledgements, declarations, contents pages, appendices, tables, diagrams and figures, references, bibliography, footnotes and endnotes) Summary Today Aneurin Bevan is a revered figure in British politics, celebrated for his role as founder one of the country’s most cherished institutions, the National Health Service. -

Anti-Fascism and Democracy in the 1930S

02_EHQ 32/1 articles 20/11/01 10:48 am Page 39 Tom Buchanan Anti-fascism and Democracy in the 1930s In November 1936 Konni Zilliacus wrote to John Strachey, a leading British left-wing intellectual and a prime mover in the recently founded Left Book Club, inviting him to ponder ‘the problem of class-war strategy and tactics in a democracy’. Zilliacus, a press officer with the League of Nations and subse- quently a Labour Party MP, was particularly worried about the failure of the Communist Party and the Comintern to offer a clear justification for their decision to support the Popular Front and collective security. ‘There is no doubt’, Zilliacus wrote, ‘that those who are on the side of unity are woefully short of a convincing come-back when the Right-Wing put up the story about Com- munist support of democracy etc. being merely tactical camou- flage.’1 Zilliacus’s comment raises very clearly the issue that lies at the heart of this article. For it is well known that the rise of fascism in the 1930s appeared to produce a striking affirmation of sup- port for democracy, most notably in the 1936 election victories of the Spanish and French Popular Fronts. Here, and elsewhere, anti-fascism was able to unite broad political coalitions rang- ing from liberals and conservatives to socialists, communists and anarchists. But were these coalitions united more by a fear of fascism than by a love of democracy — were they, in effect, marriages of convenience? Historians have long disagreed on this issue. Some have emphasized the prior loyalty of Communist supporters of the Popular Front to the Stalinist regime in the USSR, and have explained their new-found faith in democracy as, indeed, a mere ‘tactical camouflage’ (a view given retrospec- tive weight by the 1939 Nazi–Soviet Pact). -

Anti-Fascism in a Global Perspective

ANTI-FASCISM IN A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE Transnational Networks, Exile Communities, and Radical Internationalism Edited by Kasper Braskén, Nigel Copsey and David Featherstone First published 2021 ISBN: 978-1-138-35218-6 (hbk) ISBN: 978-1-138-35219-3 (pbk) ISBN: 978-0-429-05835-6 (ebk) Chapter 10 ‘Aid the victims of German fascism!’: Transatlantic networks and the rise of anti-Nazism in the USA, 1933–1935 Kasper Braskén (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) This OA chapter is funded by the Academy of Finland (project number 309624) 10 ‘AID THE VICTIMS OF GERMAN FASCISM!’ Transatlantic networks and the rise of anti-Nazism in the USA, 1933–1935 Kasper Braskén Anti-fascism became one of the main causes of the American left-liberal milieu during the mid-1930s.1 However, when looking back at the early 1930s, it seems unclear as to how this general awareness initially came about, and what kind of transatlantic exchanges of information and experiences formed the basis of a rising anti-fascist consensus in the US. Research has tended to focus on the latter half of the 1930s, which is mainly concerned with the Communist International’s (Comintern) so-called popular front period. Major themes have included anti- fascist responses to the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1935, the strongly felt soli- darity with the Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), or the slow turn from an ‘anti-interventionist’ to an ‘interventionist/internationalist’ position during the Second World War.2 The aim of this chapter is to investigate two communist-led, international organisations that enabled the creation of new transatlantic, anti-fascist solidarity networks only months after Hitler’s rise to power in January 1933. -

Narratives of Delusion in the Political Practice of the Labour Left 1931–1945

Narratives of Delusion in the Political Practice of the Labour Left 1931–1945 Narratives of Delusion in the Political Practice of the Labour Left 1931–1945 By Roger Spalding Narratives of Delusion in the Political Practice of the Labour Left 1931–1945 By Roger Spalding This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Roger Spalding All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0552-9 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0552-0 For Susan and Max CONTENTS Preface ...................................................................................................... viii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter One ............................................................................................... 14 The Bankers’ Ramp Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 40 Fascism, War, Unity! Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 63 From the Workers to “the People”: The Left and the Popular Front Chapter -

'The Trojan Horse': Communist Entrism in the British Labour Party

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Campbell, Alan and McIlroy, John (2018) ’The Trojan Horse’: Communist entrism in the British Labour party, 1933-43. Labor History, 59 (5) . pp. 513-554. ISSN 0023-656X [Article] (doi:10.1080/0023656X.2018.1436938) Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/23927/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

Border Country: Raymond Williams in Adult Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 358 300 CE 063 833 AUTHOR Mcllroy, John, Ed.; Westwood, Sallie, Ed. TITLE Border Country: Raymond Williams in Adult Education. INSTITUTION National Inst. of Adult Continuing Education, Leicester (England). REPORT NO ISBN-1-872941-28-1 PUB DATE 93 NOTE 351p. AVAILABLE FROMNational Institute of Adult Continuing Education, 19B De Montfort Street, Leicester LE1 7GE, England, United Kingdom (12.99 British pounds). PUB TYPE Books (010) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC15 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adult Education; Adult Educators; Adult Learning; Adult Literacy; Biographies; *Cultural Awareness; Cultural Education; Educational History; *Educational Philosophy; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; Interdisciplinary Approach; Literacy Education; Literary Criticism; Literature; *Popular Culture; Soeirl Change; Social Science Research IDENTIFIERS Great Britain; *Williams (Raymond) ABSTRACT This volume brings together a collection of writings from 1946-61 by Raymond Williams, a British university adult educator. Section 1is a brief account by Mcllroy of Williams' involvement in teaching adults, his intellectual influences, and the relationship of his educational and intellectual life to his personal experience and political concerns. Section 2 is a selection of Williams' published work that documents his chief intellectual concerns. It presents 14 writings ranging from pieces in the journals "Politics and Letters" and "The Critic" through early essayson the theme of culture and society to his review of "The Uses of Literacy," an extended dialogue with Richard Hoggart, and a contemporary evaluation of the New Left. Section 3 illustrates the changing curriculum and methods of literature teaching in university adult education and illuminates, in 12 articles on teaching culture and environment, public expression and film criticism, the beginnings of today's cultural studies. -

Labour's Everyman, –

ch1-2.008 7/8/02 2:44 PM Page 1 Labour’s Everyman, – On April a group of figures appeared on the Northumberland horizon walk- ing slowly in the brilliant sunlight along Hadrian’s Wall. Included in the party were officials of local antiquarian societies, civil servants, businessmen, and newspaper reporters. In the midst was the Cabinet minister from Whitehall: a large-framed seventy-year-old man, with white hair and ruddy face adorned by mutton-chop whiskers, attired in an old alpaca suit and bowler hat. Instantly recognized wherever he went, he possessed an unmistakable ringing voice, in which he greeted everyone as his friend. At Housesteads, the official retinue stopped to concentrate on the silent stones. Characteristically, the minister conversed warmly with the eighty-one-year-old keeper of the fortification, Thomas Thompson, before pondering the moral and political dilemma revealed by the threat of extensive quarrying to the Roman Wall. As the Cabinet minister in the second Labour government responsible for national monuments and historic sites, George Lansbury was steeped in British his- tory. However, he recognized that , tons of quarried stone provided the pos- sibility of permanent employment in a region blighted by the inter-war Depression, but only at the expense of one of the most striking and beautiful stretches of the ancient monument.1 In Britain today, George Lansbury is probably remembered best, not as the First Commissioner of Works, but as the humanitarian and Christian pacifist leader of the Labour Party, apparently out of touch with the realpolitik of European affairs in the s.